Given-When-Then Acceptance Criteria for Better User Stories

What is the Given-When-Then format? Discover how to use this framework for acceptance criteria with real-world examples and 2026 Gherkin templates. Start writing!

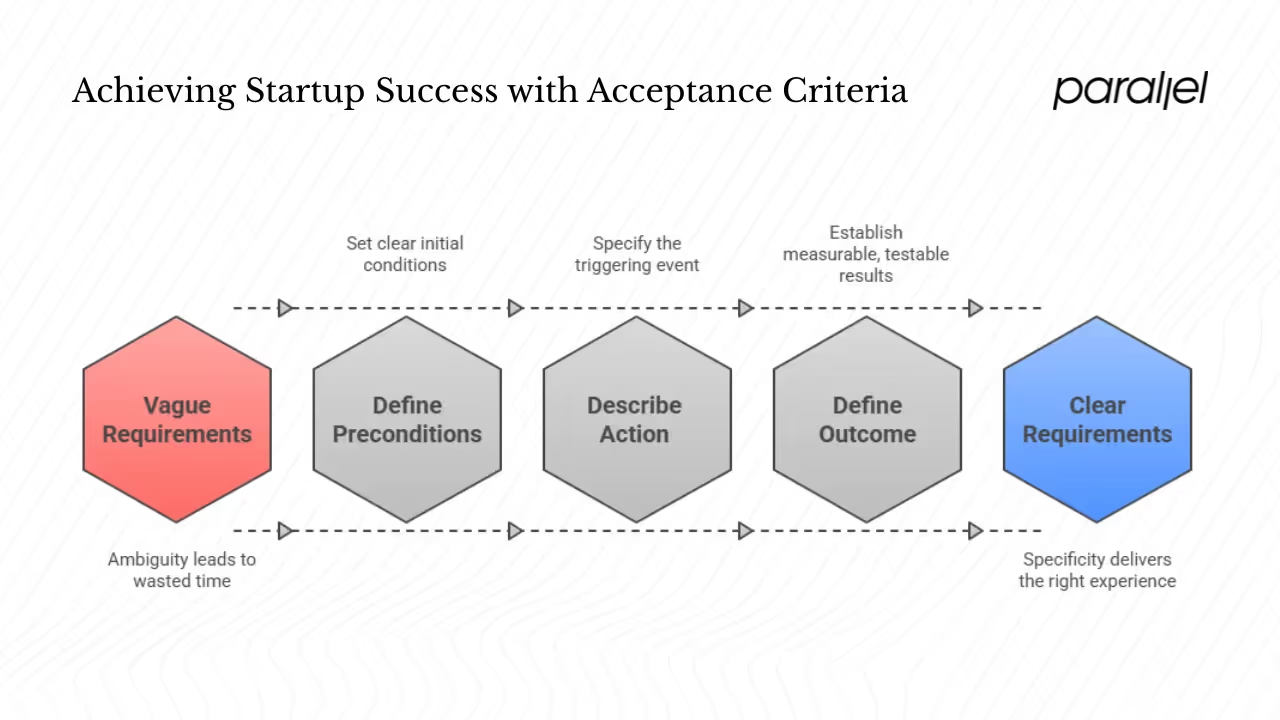

Meet G‑W‑T: the magic formula that turns wishy‑washy requirements into crystal‑clear outcomes. Every startup founder or product leader has felt the pain of vague feature requests like “make it fast” or “improve the user experience.”

Without structure, those phrases invite endless interpretation and rework. The given when then acceptance criteria format solves that problem by providing a simple pattern for writing acceptance tests for user stories: Given some context, When some action is carried out, Then the observable consequences should follow.

Invented in the early 2000s and codified by the Agile Alliance, this template guides teams toward shared understanding before development begins, making ambiguous requirements testable and actionable. For early‑stage startups, that clarity translates directly into velocity and quality.

Quick Guide: Given–When–Then Acceptance Criteria

- Why use it?

To turn vague requirements into testable, clear outcomes that developers, designers, and testers can all agree on. - The structure:

- Given some context or starting state

- When an action happens

- Then a specific result should follow

- Given some context or starting state

Example:

Given a user is on the signup page

When they submit valid details

Then the system creates an account and sends a confirmation email

- When to write it?

During backlog grooming or sprint planning—before development starts. - Common mistake to avoid:

Don’t say “make it fast” or “nice UX.” Be specific: “results load in under 200 ms” or “checkout completes in 3 steps.”

What is Given–When–Then (GWT) Acceptance Criteria?

Given–When–Then (GWT) is a format for writing testable acceptance criteria using a three-part structure:

- Given a specific starting condition,

- When an action is taken,

- Then an expected result should occur.

This method removes ambiguity from requirements, helps teams align before coding begins, and supports automated testing tools like Cucumber and SpecFlow.

Why GWT matters for startups?

Startups thrive on rapid iteration, but speed without alignment is chaos. A hacky workaround might satisfy today’s demo but break tomorrow’s roadmap. The given when then acceptance criteria approach bridges the gap between ambiguity and action by turning fuzzy desires into measurable targets. Instead of “the search should be fast,” the criteria might read: “Given a catalog of 1,000 items, when the user searches for ‘t-shirt’, then results load in under 200 ms.” This phrasing sets preconditions, describes the trigger, and defines a clear, testable outcome. According to Smartsheet, vague criteria like “fast” or “nice UX” cause misunderstandings and waste time; quantifiable statements such as “response < 200 ms” or “user can complete checkout in three steps” eliminate confusion.

At early‑stage companies, the founders, product managers and design leaders often double as QA and support. They need criteria that validate not just functionality but also user experience, security and regulatory needs. Acceptance criteria serve as a bridge between high‑level goals and low‑level test scenarios, connecting terms such as preconditions, postconditions, workflow validation and test scenarios. ProductPlan describes acceptance criteria as a definition of done—pre‑defined, testable requirements that must be met before a user story is considered complete. With those requirements agreed upon, teams can break ideas into small increments, deliver value frequently and avoid rework.

As founders ourselves, we at Parallel have seen early‑stage AI and SaaS teams struggle when acceptance criteria are missing or too broad. One client aimed to “make onboarding delightful.” Weeks later, engineers built animations while the CEO wanted a seamless SSO flow. Once we wrote given when then acceptance criteria for the onboarding story—defining preconditions (user arrives with an invite), the action (enters a password) and the outcome (account activated, personalized welcome email delivered within 30 seconds)—the team stopped guessing and delivered the right experience in two sprints. That’s the power of specificity.

Behavior‑driven development & GWT

The given when then acceptance criteria format didn’t appear out of thin air; it comes from Behavior‑Driven Development (BDD), an agile methodology that emphasises collaboration among developers, testers and business stakeholders. BDD uses a common language to describe software behavior so that everyone shares the same understanding. At its core is a domain‑specific language called Gherkin, which divides business requirements into scenarios written in natural language. Each scenario uses the Given–When–Then syntax to describe a piece of functionality. According to Keploy’s overview of BDD, detailed scenarios illustrate behavior using the Given, When, Then format and serve as clear acceptance criteria that define when a user story is complete.

BDD matters because it turns acceptance criteria into living documentation. Instead of writing requirements in isolation, cross‑functional teams collaborate to craft scenarios. TestRail notes that BDD addresses miscommunication by encouraging cross‑functional collaboration and a shared language to define expected behaviors, reducing vague or incorrect requirements. The method leverages tools like Cucumber, SpecFlow or Behave to turn the scenarios into executable tests, giving rapid feedback and enabling continuous delivery. Importantly, BDD aligns product owners, designers, developers and QA; TestRail stresses that the “Three Amigos” practice brings together a product owner, developer and tester to define and refine scenarios, ensuring that business goals, technical feasibility and test coverage are considered. For startups with small teams wearing many hats, adopting BDD and its GWT syntax ensures everyone speaks the same language.

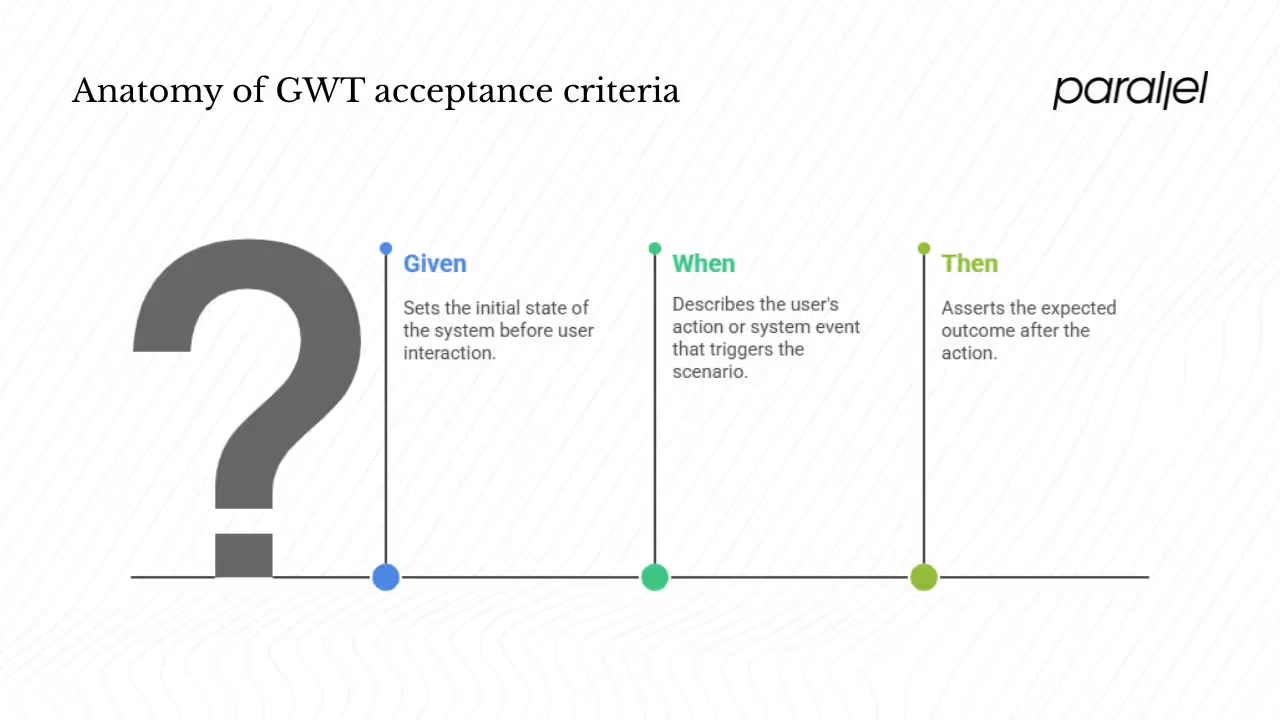

Anatomy of GWT acceptance criteria

A well‑written GWT acceptance criterion is more than a sentence; it’s a contract. Each part performs a specific role:

- Given – sets the context and preconditions. It describes the state of the system before the user interacts. For example, “Given the user navigates to the login page…” sets up the initial condition for a forgot‑password flow.

- When – triggers the action. It focuses on the user’s behavior or system event that initiates the scenario. “When the user enters their email address and clicks Forgot Password…” describes the user’s action.

- Then – asserts the expected outcome. It defines what should happen after the action. “Then the system sends a password recovery link to the email.” This is the postcondition that testers can validate.

Real examples make the structure tangible. AltexSoft offers a forgot‑password scenario: “Given the user navigates to the login page, when the user selects Forgot password and enters their email, then the system sends a recovery link”. Another scenario covers successful user registration: “Given a user is on the signup page, when the user enters a valid email and password, then the account is created and an activation email is sent”. ProductSchool extends that registration example by stating that after a valid submission the system should create a new account, redirect the user to a welcome page and send a confirmation email. These examples show how the Given describes the context, When triggers the behavior, and Then specifies multiple outcomes, such as sending an email and redirecting to a new page.

Writing GWT acceptance criteria: practical steps

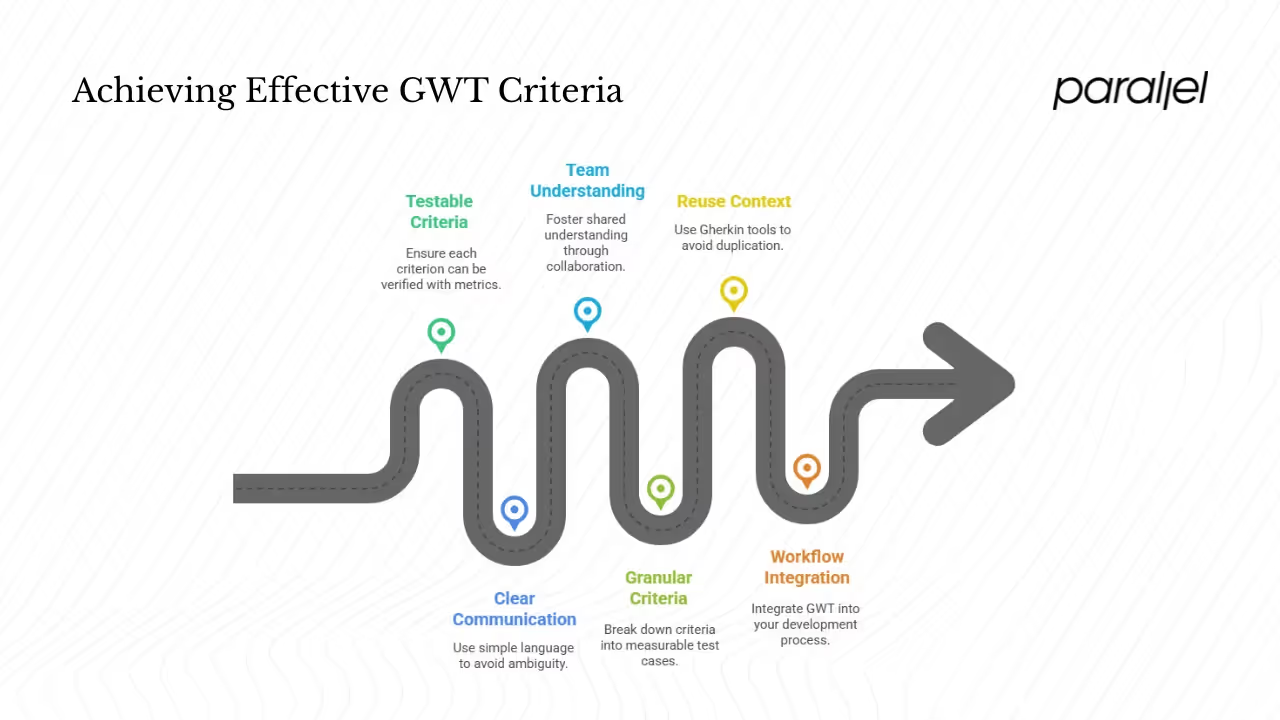

1. Make criteria testable

If a criterion isn’t testable, it’s not useful. Ensure each Then statement can be verified. Avoid subjective phrases like “intuitive” or “fast” without metrics. Smartsheet warns that ambiguous terms such as “fast” or “nice UX” are untestable and lead to confusion; instead, quantify performance targets and outcomes. Consider the difference between “mobile responsive” versus “Given a viewport of 375 × 667 px, when the user opens the page, then the layout adjusts without horizontal scrolling.”

2. Be clear and concise

Use simple language. Qase advises keeping acceptance criteria simple and user‑centric, using active voice and avoiding implementation details. Each scenario should focus on one behavior; long compound sentences are harder to test and maintain. At Parallel we encourage teams to limit scenarios to three or four steps. If you find yourself writing “and then” repeatedly, split the scenario.

3. Ensure team understanding

Acceptance criteria are meant to foster shared understanding. Qase emphasises that they should be created collaboratively before development, involving developers, testers and stakeholders to ensure consensus. The TestRail “Three Amigos” practice formalises this collaboration. In practice, schedule brief sessions during backlog grooming or sprint planning where the team writes criteria together. Use a digital whiteboard or real whiteboard so everyone can contribute.

4. Strive for granularity

Break vague criteria into measurable test cases. Instead of “works on mobile,” write separate scenarios for different devices or breakpoints. Decomposing criteria ensures each piece can pass or fail individually. Overly broad acceptance criteria become mini‑specifications and are hard to automate. When crafting given when then acceptance criteria for performance or security, consider writing multiple scenarios that isolate each requirement—one for throughput, another for latency, and another for edge cases.

5. Reuse context with backgrounds and scenario outlines

Gherkin offers tools to avoid duplication. Nestify explains that the Background keyword lets you define steps common to all scenarios, reducing redundancy. Scenario outlines combined with example tables allow you to test multiple data sets without rewriting the scenario. For instance, you can write a registration scenario once and provide a table of valid and invalid email/password combinations. This keeps your criteria DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) and easier to maintain. When teams share a common setup—say they always start on the dashboard—moving those lines into a Background ensures that each given when then acceptance criteria scenario begins with the same context without repeating the steps.

6. Integrate GWT into your workflow

Write acceptance criteria during backlog refinement or sprint planning. Qase notes that acceptance criteria should exist before development begins. However, avoid writing them too early; you need enough context to articulate the scenario. Many teams create high‑level criteria when a story is created and refine them as they approach the sprint. Tools like Jira or Clubhouse support Gherkin formatting right in the ticket description, making them easy to store and reference.

Common pitfalls & fixes

1) Vague or high‑level language

The most common mistake is writing vague phrases like “fast,” “user‑friendly” or “good UX.” Smartsheet highlights that such words make acceptance criteria untestable and ambiguous. Fix: quantify performance: “search returns results within 200 ms,” or define UX outcomes: “users complete checkout in under three steps without error messages.”

2) Over‑formalizing the document

Some teams turn acceptance criteria into mini‑requirements documents. This is contrary to Agile’s conversation‑first mindset. Qase stresses that acceptance criteria are guidelines, not exhaustive specifications. Fix: focus on the outcome and conversation; leave implementation details to the team.

3) Duplicating story content

Duplicating the entire story in the acceptance criteria makes tickets messy and repetitive. The story should describe the value and narrative; the criteria should describe testable outcomes. Fix: keep the narrative and test cases separate; they complement each other rather than echoing.

4) Ignoring non‑functional requirements

Startups often overlook performance, security or accessibility until late. Non‑functional requirements can be expressed using GWT as well. For example: “Given a mobile device with a slow network, when the user submits the form, then the loading spinner persists until the data is saved and the user receives a confirmation within 2 seconds.” Consider adding scenarios for accessibility, such as keyboard navigation or screen‑reader support.

Putting it all together: example workflow

Let’s walk through a mini‑case to illustrate how given when then acceptance criteria work in practice. Imagine you are building a scoring feature for a product‑roadmap tool. The user story reads: “As a product manager, I want to score ideas to rank them by benefit versus cost.” The acceptance criteria could be written as:

Scenario: Product manager scores ideas and ranks them

- Given two or more ideas are scored using a benefit‑vs‑cost model

- When the product manager clicks Rank

- Then the ideas are sorted with the highest‑scoring idea at the top

This scenario covers the essential test cases: verifying that at least two ideas are scored, that the ranking action triggers the sort, and that the results appear in descending order. It also implicitly checks that the scoring model exists and that the UI updates. When the team builds and tests this feature, they will know exactly what constitutes success. Later, they can extend the criteria with more scenarios—sorting by ascending order, handling ties or multi‑criteria scoring—without rewriting the story.

Takeaways for your startup future

Adopting given when then acceptance criteria amplifies clarity, reduces uncertainty and accelerates delivery. By turning ambiguous desires into testable statements, you create alignment across founders, PMs, designers and engineers. The practice makes acceptance tests easier to automate via frameworks like Cucumber or Selenium—although automation is not the only value. Living documentation fosters shared understanding, and automation simply provides continuous validation. In our work with AI and SaaS startups, teams that adopt GWT and BDD see fewer bugs, faster onboarding of new hires and more predictable releases.

Startups operate in a world of unknowns. By writing acceptance criteria that describe not just functional outcomes but also performance, security, and user experience constraints, you de‑risk your roadmap. BDD frameworks turn these criteria into executable tests, ensuring that every change satisfies the agreed‑upon behavior. Celerity’s guide emphasises that BDD improves communication, increases test quality and accelerates development by using a common language and scenarios that are easy for both technical and business teams to understand. TestRail adds that BDD helps teams reduce the learning curve, improve communication and build confidence in every release. When paired with the right tools, GWT becomes a mechanism for continuous improvement.

Conclusion

The power of given when then acceptance criteria lies in transforming vague direction into precise action. In our experience, startups that adopt this approach deliver features faster, with fewer defects and less friction. GWT fosters alignment across roles, makes requirements testable and provides a foundation for automation. For early‑stage teams juggling product strategy, design and engineering, clarity is your greatest asset. Don’t wait until a project derails to define success—write your acceptance criteria early, make them measurable and collaborate across the team. By embracing GWT today, you set your product up for better storytelling, better outcomes and a more resilient future.

FAQ

1) How do you write acceptance criteria using Given–When–Then?

Start by defining the Given context or precondition, then specify the When action or trigger, and finally describe the Then expected outcome. Ensure each statement is testable and written in plain language. According to the Agile Alliance, this template guides acceptance tests for user stories by mapping context, action and consequence.

2) What is an example of Given–When–Then?

A common example is the forgot‑password scenario: Given the user navigates to the login page, When the user selects “Forgot password” and enters their email, Then the system sends a recovery link. Another is successful registration: Given a user is on the signup page, When valid data is submitted, Then a confirmation email is sent and the user is redirected.

3) What is a good example of acceptance criteria?

The ProductPlan scoring example shows how acceptance criteria can clarify business rules: Given two or more ideas are scored, When the product manager clicks Rank, Then the ideas are sorted with the highest‑scoring idea first. This succinctly covers the necessary preconditions, action and outcome and can be executed manually or via automated tests.

4) Why is it called the Gherkin acceptance criteria?

The term comes from Gherkin, a domain‑specific language used in BDD tools such as Cucumber. Gherkin uses keywords like Given, When, Then, And and But to structure scenarios. The resulting scripts look like plain English but have a predefined grammar that both humans and machines can interpret, allowing developers, testers and business stakeholders to share a common language. Hence, acceptance criteria written in this style are often called Gherkin acceptance criteria.

.avif)