How to Create a Design Brief: Complete Guide (2026)

Learn the steps to create a comprehensive design brief, including defining goals, audience, scope, and deliverables.

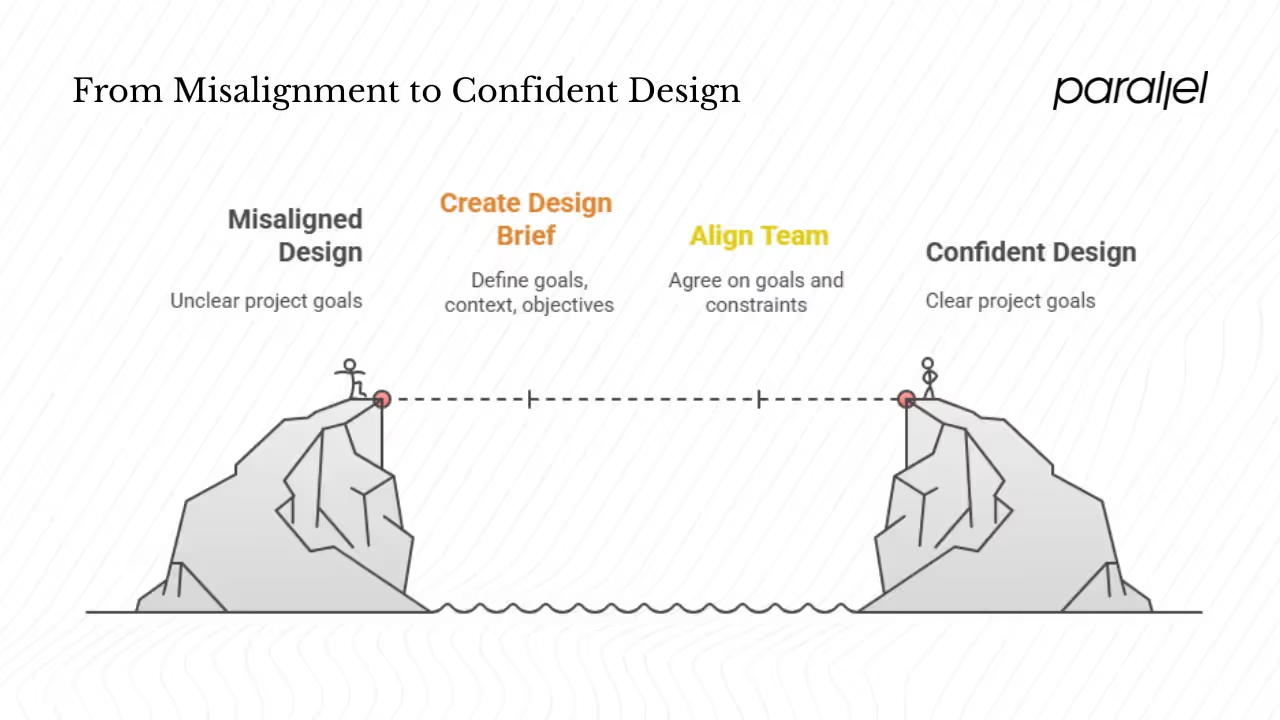

Misaligned expectations kill good ideas. In Project.co’s 2025 communication survey, 63% of people said they waste time because of communication issues and 68% even moved to a competitor due to poor communication. Over the years I’ve seen messy feedback cycles and repeated revisions derail projects and exhaust teams. A well‑structured design brief acts as a shared contract between founders, product managers, designers and engineers and prevents that waste. This article explains how to create a design brief that reduces miscommunication, aligns goals and lets creativity flourish within clear boundaries.

TL;DR: How to Create a Design Brief

A design brief is your project’s north star — a concise, collaborative document that defines what you’re building, why it matters, who it’s for, and how success is measured. It aligns stakeholders, reduces miscommunication, and speeds up delivery. To create one, follow this 11-step structure covering context, goals, users, visual direction, technical requirements, and more. A strong design brief sets clear expectations and unlocks creative results.

Why design briefs matter

At its core, a design brief is a simple document that describes what you want to build, why you’re building it and how you’ll know you’ve succeeded. Asana’s definition emphasises alignment: a brief outline of the project’s core details and expectations in an easy‑to‑understand plan. The Interaction Design Foundation adds that a good brief includes context, background and measurable objectives. Without this grounding, teams make assumptions and drift off course. Miscommunication doesn’t just slow you down; it costs money and erodes trust. When 94% of first impressions online are influenced by design and 75% of people judge a company’s credibility based on its site, a sloppy process can tank your business before users give you a chance.

Design briefs are especially vital for lean teams. When budgets are tight and priorities shift quickly, there’s no room for endless iterations or guesswork. At Parallel we’ve seen founders save weeks of back‑and‑forth simply by investing a few hours up front to agree on goals and constraints. Knowing how to create a design brief helps small teams move confidently and reduces friction when new teammates join mid‑project.

Design brief vs other briefs

People often confuse design briefs with creative or project briefs. A design brief focuses on business context, goals, constraints and high‑level requirements. A creative brief digs into tone of voice, messaging and art direction, and a project brief may include engineering or marketing components. Start with a design brief to align on the “why” and “what”; use a creative brief later when you explore the “how.”

Principles of a good design brief

Before we dive into structure, it’s helpful to outline the traits of an effective brief. These principles come from research, industry guidance and lived experience:

- Concise and comprehensive: Each section should be focused. Avoid jargon and filler. Asana notes that the brief should be an easy‑to‑understand plan.

- Specific and measurable: Define success using metrics like conversion rate or user satisfaction. IxDF emphasises the importance of clear objectives.

- Modular and scannable: Use headings and lists so stakeholders can quickly find what matters to them.

- Living and versioned: Update the brief as research and requirements evolve. IxDF encourages regular reviews to stay aligned.

- Collaborative: Create the brief with input from designers, engineers and product owners; collaborative briefs lead to fewer misunderstandings.

- Signed off: Secure approval from decision‑makers so the team doesn’t drift into subjective feedback.

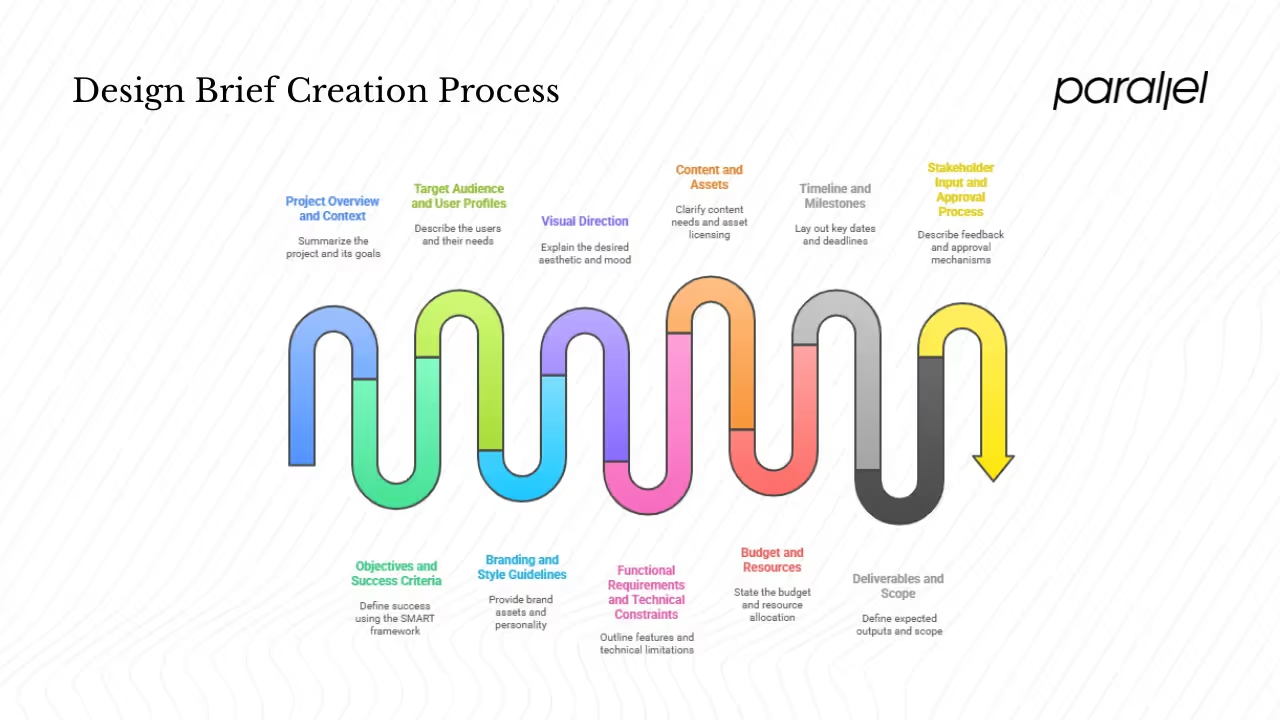

Step‑by‑step structure: what to include

Understanding how to create a design brief means knowing which sections to cover. Here are the core components and why they matter:

1. Project overview and context

Summarise the project in a sentence or two: what you’re designing (e.g., onboarding flow, brand refresh), why you’re doing it now and how it ties to broader company goals. List key stakeholders and decision‑makers. Asana suggests starting with company details and past projects to build trust. This context prevents designers from solving the wrong problem.

2. Objectives and success criteria

Define what success looks like. Use the SMART framework: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time‑bound. Goals might include increasing sign‑ups by 20%, reducing bounce rate or improving net promoter score. Also state what the project is not aimed to do, so scope doesn’t balloon. Clear objectives help designers make trade‑offs and provide a yardstick for feedback.

3. Target audience and user profiles

Describe who will use the product. Include demographic details (age, location, job titles) and psychographic insights (pain points, motivations). Distinguish between existing customers and new segments. IxDF notes that strong briefs reflect solid user research. If multiple personas exist, prioritise them and highlight behaviour patterns like device usage or channel preferences.

4. Branding and style guidelines

Provide brand assets—logos, colors, typography—and describe the brand’s personality (approachable, authoritative, playful). Include mandatory elements like taglines or legal copy. Indicate whether there’s room for experimentation. Because design influences credibility, alignment with existing brand identity is crucial.

5. Visual direction

Explain the desired aesthetic: minimalist, bold, illustrative, photorealistic or playful. Provide mood boards or links to designs you admire and specify what to avoid. Align on color schemes and typography choices. Doing this early reduces subjective feedback later.

6. Functional requirements and technical constraints

Outline features and behaviours: forms, animations, integrations or accessibility standards. Specify target platforms (web, iOS, Android) and performance expectations. IxDF’s guidance on design specifications reminds us to include technical requirements to prevent infeasible designs.

7. Content and assets

Clarify who will write the copy and what tone it should take. Describe imagery needs (illustrations versus photography) and asset licensing. If charts or videos are needed, mention them. Decide how dynamic content will be handled. Early agreements prevent bottlenecks and blank placeholders.

8. Budget and resources

State the total budget and how it’s allocated—concepting, design, development, revisions, asset purchases. Identify resource constraints such as team bandwidth. Hidden costs (like third‑party software licences) should be documented to avoid surprises. Transparency ensures design concepts align with financial reality.

9. Timeline and milestones

Lay out key dates: kickoff, concept presentation, feedback rounds and final delivery. Distinguish between hard deadlines (e.g., marketing launch) and flexible ones. Build in buffer for feedback and dependencies. IxDF underscores the need for realistic timelines and clear expectations.

10. Deliverables and scope

Define what you expect to receive: high‑fidelity mockups, prototypes, design system tokens, dark mode variations and documentation. Indicate file formats and acceptance criteria. This section prevents misunderstandings about what “done” means.

11. Stakeholder input and approval process

List who will give feedback and at which stages. Describe how feedback will be collected—annotation in Figma, shared documents or structured meetings. Clarify who has the final sign‑off. Without a clear process, you risk endless revisions and frustration.

Design Brief Structure – 11-Step Summary

Tips for writing and managing your brief

Learning how to create a design brief doesn’t end with drafting; managing it well is just as important. Here are five practical tips:

- Use an intake questionnaire: Collect basic information from stakeholders before you meet. This surfaces questions and saves time.

- Collaborate early: Host a kickoff workshop to fill out the brief together. This fosters buy‑in and surfaces hidden assumptions.

- Prioritise and label: Separate “must‑have” from “nice‑to‑have.” When budgets or timelines get squeezed, you know what to cut.

- Version control: Date each version and summarise changes. Regularly review and update the document to reflect new research or pivots.

- Link feedback back to the brief: Every request should map to a goal or constraint. If not, either adjust the brief or defer the request.

Real‑world example

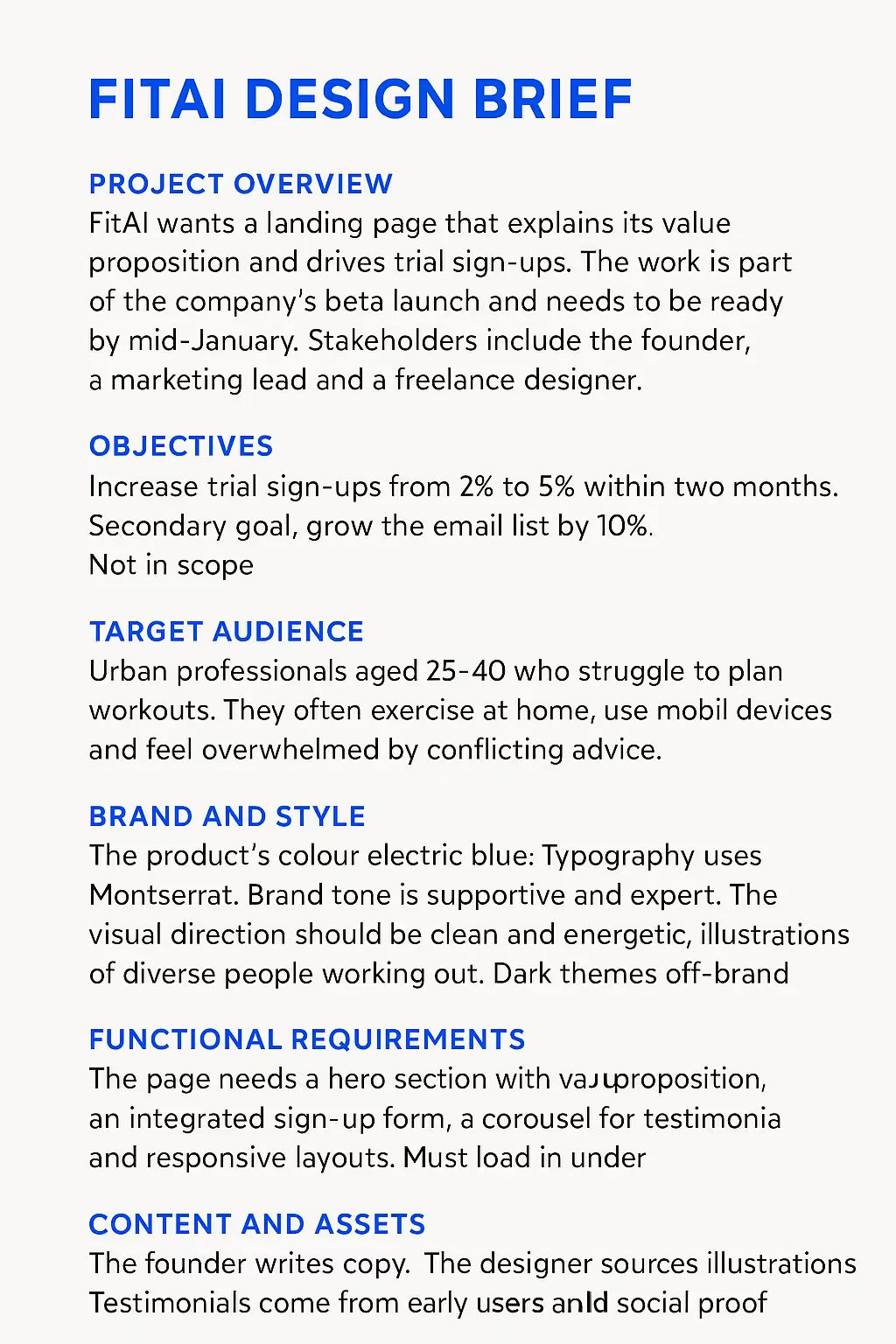

To illustrate how to create a design brief, let’s look at a simplified example. FitAI is a fictional SaaS startup that provides personalised workout plans through machine learning. They need a high‑converting landing page for their beta launch.

Project overview: FitAI wants a landing page that explains its value proposition and drives trial sign‑ups. The work is part of the company’s beta launch and needs to be ready by mid‑January. Stakeholders include the founder, a marketing lead and a freelance designer.

Objectives: Increase trial sign‑ups from 2% to 5% within two months. Secondary goal: grow the email list by 10%. Not in scope: building a blog.

Target audience: Urban professionals aged 25–40 who struggle to plan workouts. They often exercise at home, use mobile devices and feel overwhelmed by conflicting advice.

Brand and style: The product’s colour is electric blue; typography uses Montserrat. The brand tone is supportive and expert. The visual direction should be clean and energetic, with illustrations of diverse people working out. Dark themes are off‑brand.

Functional requirements: The page needs a hero section with a value proposition, an integrated sign‑up form, a carousel for testimonials and responsive layouts. It must load in under two seconds and meet WCAG AA accessibility.

Content and assets: The founder writes the copy. The designer sources illustrations. Testimonials come from early users. Real‑time metrics on workouts generated add social proof.

This concise example demonstrates how each section guides decisions. When questions arise—such as whether to add a blog section—the brief provides a clear answer (“out of scope”). Once you know how to create a design brief like this, you can adapt the framework to projects of any size.

Common mistakes to watch out for

- Ambiguous goals: Goals like “make it modern” lack metrics and invite subjective debate.

- Scope creep: Adding deliverables mid‑project without adjusting budget or timeline derails progress.

- Skipping feedback cycles: A brief is a conversation. Without scheduled check‑ins and updates, misalignment grows.

- Ignoring technical constraints: Designs that can’t be built waste everyone’s time. Collaborate with engineers early.

- No single owner: When everyone can approve changes, no one feels accountable. Decide who has final say.

Conclusion

A thoughtful brief anchors creativity. It aligns teams, reduces miscommunication and keeps the project on budget. Good design pays off: user interface improvements can increase conversions by as much as 200%, while 38% of users abandon sites with unattractive layouts. Once you know how to create a design brief—define context, set measurable goals, understand your audience, capture constraints, specify deliverables and agree on a process—you can replicate the approach across projects. Invest the time up front and you’ll save countless hours later.

Frequently asked questions

1) What does a graphic design brief look like?

A good design brief is usually one or two pages long and clearly structured. It covers the project overview, goals, audience, deliverables and constraints. The Interaction Design Foundation points out that the brief should capture context, objectives and target users to guide designers.

2) How do I write a brief example?

Start with a short description of what you’re designing and why. Outline measurable goals, describe your target audience, share branding and style guidelines, list functional requirements, set a budget and timeline and define the deliverables. This structure shows how to create a design brief in a way that is actionable and clear.

3) Who writes a design brief?

Typically, the project owner—founder, product manager or marketing lead—drafts the initial brief. Key stakeholders and the design team contribute insights. IxDF notes that clients, stakeholders and designers all play roles in creating the brief. The important part is alignment, not strict ownership.

4) How often should I update the brief?

Any time significant information changes. Regular reviews keep the document relevant and prevent miscommunication. Many teams revisit the brief before each new phase of work to confirm that goals and constraints still hold.

.avif)