How to Create a Great Product: Complete Guide (2026)

Explore methods to create a great product, from identifying customer needs to iterating on design and delivering exceptional value.

Building something useful isn’t a matter of luck. Every founder and product leader has wondered how to create a great product at some point. A “product” is more than features or code; it’s an experience that solves a problem and fits into people’s lives. In this guide I’ll share a simple, first‑hand playbook that has worked for us at Parallel and for early‑stage startups we’ve helped. The goal isn’t to give you a silver bullet. It’s to offer principles and tactics that will help you decide how to create a great product in your own context.

TL;DR – How to Create a Great Product

To create a great product, start by deeply understanding your users and the problem they face. Validate your ideas through real conversations and market research. Use design thinking to explore solutions, build fast prototypes, and iterate with real feedback. Focus on delivering the core value early with an MVP. Track metrics like retention and satisfaction to guide improvement. When launching, tell a clear story and continue learning from users.

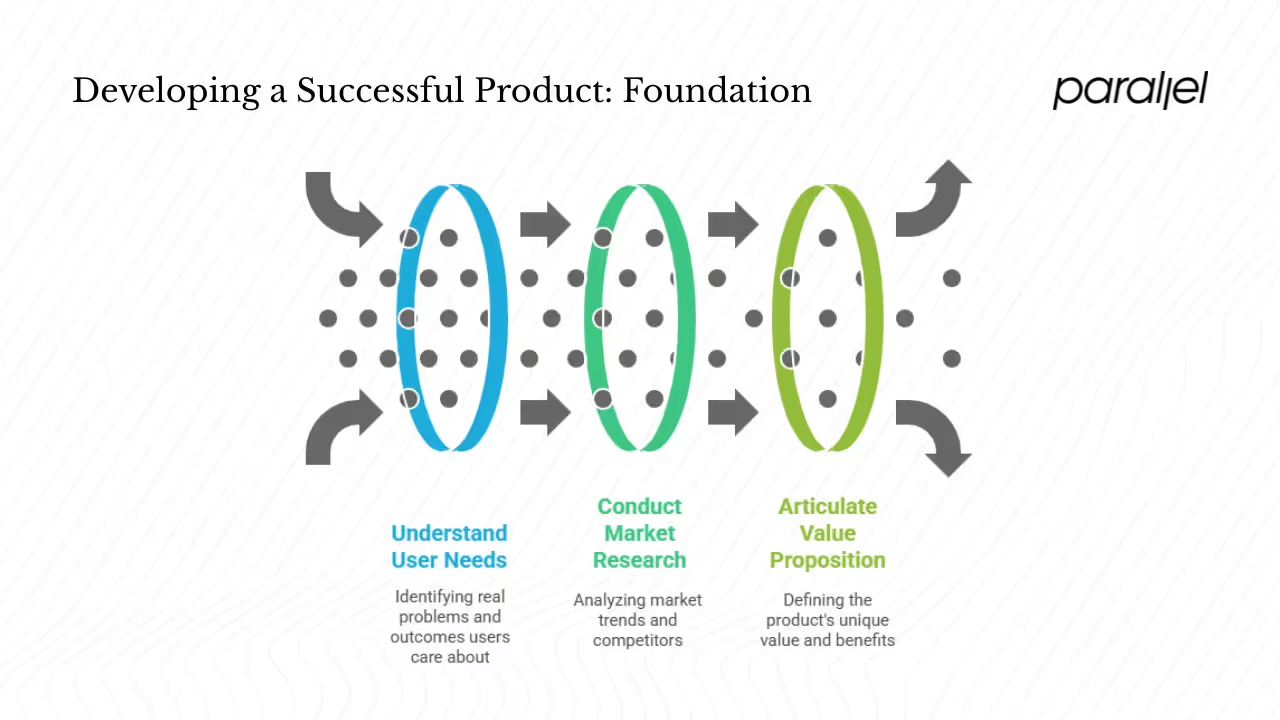

Step #1: Foundations– get the why right

Understand user needs

Products succeed when they solve real problems. Sounds obvious, yet many teams jump into solution mode without clarifying the problem. Needs are the underlying jobs or outcomes people care about. Wants are features users think they want, and pain points are the frustrations they feel today. Misclassify wants or pain points as needs and you risk solving the wrong problem. Spend time with people to learn what they do, say, think and feel. Interviews, field observation and surveys will show you patterns you won’t see from a desk. Empathy maps and customer experience maps help you synthesise this insight.

The design thinking framework starts with empathy for a reason. Nielsen Norman Group’s description of the process lists six stages: empathise, define, ideate, prototype, test and implement. Empathising helps you avoid building imaginary solutions. In our experience working with machine‑learning SaaS teams, weekly conversations with real users during discovery keep the product grounded. Don’t rely on your own perspective alone; your context is only one use case.

Do your market research

User insight is vital, but it exists within a broader market. Study adjacent markets, substitutes and emerging trends such as the rise of generative interfaces. Analysing competitors helps you spot gaps, opportunities and potential threats. Tools like SWOT analysis, feature benchmarking and positioning maps help you understand where your idea sits. Competitive analysis isn’t about cloning others; it’s about making informed choices about differentiation.

Articulate a clear value proposition

You need to tell customers why your product matters. A strong value proposition states the problem you solve, the outcome you enable and why your approach is better than alternatives. It balances value against feasibility and cost. Specific outcomes are more convincing than buzzwords. For example, instead of “we use machine learning to improve onboarding,” say “we help new users get up to speed in five minutes.” Test your value proposition early through conversations, surveys or landing pages. Adjust it based on feedback. In our work, we’ve found that testing pricing alongside value propositions can uncover who is truly willing to pay.

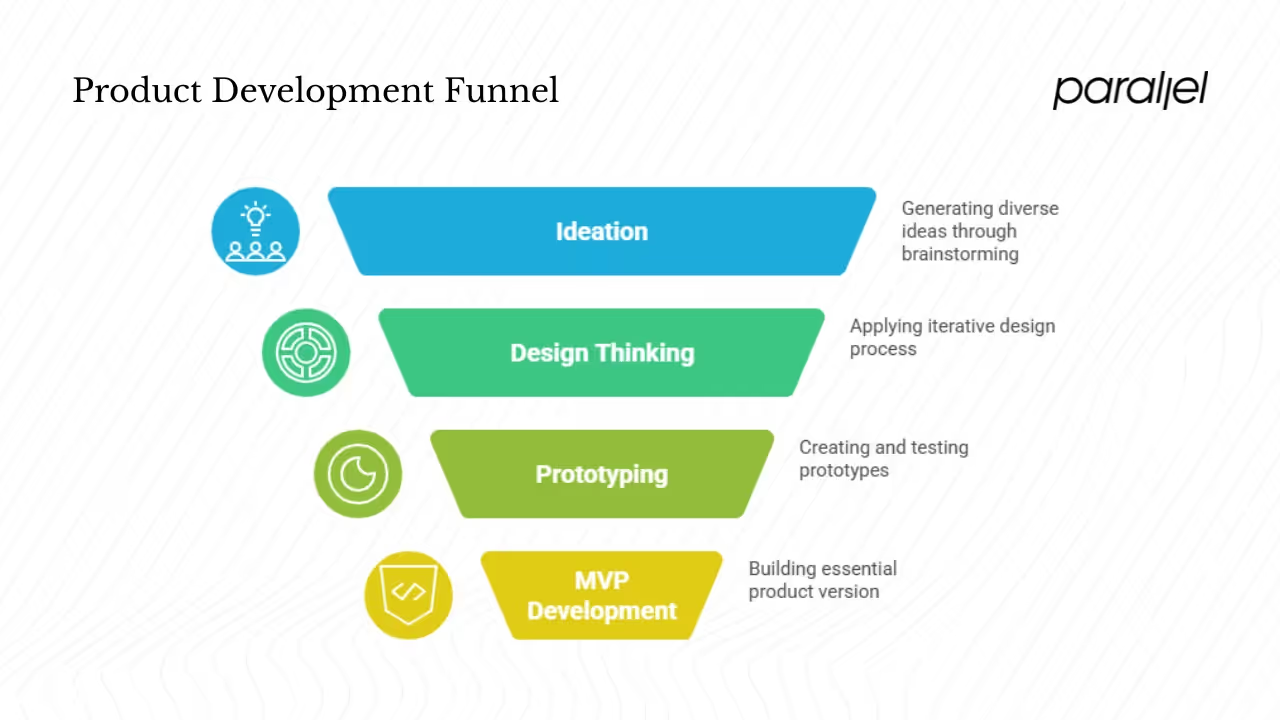

Step #2: Ideation, innovation and design thinking

Generate ideas that matter

Great ideas rarely come from a vacuum. They come from mixing user insights with technology shifts and inspiration from adjacent spaces. At Parallel we draw from complaints, unmet needs, tech trends and “what if” questions. Structured brainstorms, hackathons and cross‑functional ideation sessions encourage a broad range of concepts. The SCAMPER framework (substitute, combine, adapt, modify, put to another use, eliminate, reverse) is a practical tool for reframing existing solutions.

Quantity matters at this stage. Withhold judgement until you have many possibilities on the table. Doing this groundwork is a vital part of how to create a great product.

Apply design thinking

Design thinking is a practical tool kit, not a buzzword. After empathising and defining the problem, you move into ideation, prototyping and testing. The process is iterative; you don’t march forward linearly but loop back as you learn. Build small prototypes to try solutions quickly, learn what works and what doesn’t, and adjust. The final step, implementation, reminds us that ideas must be shipped. Without execution, even the best concept is meaningless.

Prototype and build your MVP

Prototypes range from paper sketches to high‑fidelity mock‑ups. Early, low‑fidelity prototypes are inexpensive and let you try different directions, while high‑fidelity prototypes help you refine interaction details. When you’re ready, build a minimum viable product (MVP) — a version that delivers the core benefit to a small group of users. An MVP isn’t a half‑baked product; it includes only the essentials and leaves out the extras. Define what “viable” means: which assumptions you’re testing and what success looks like. Test it with real users before scaling and iterate based on what you learn.

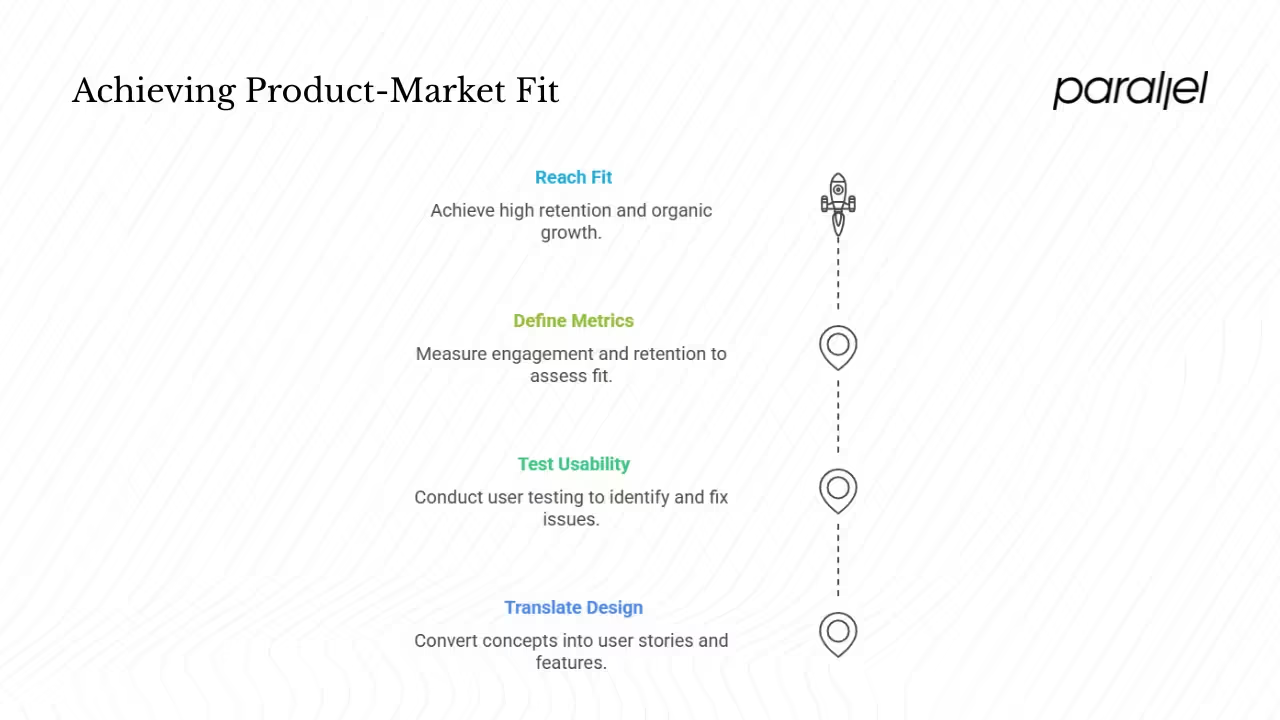

Step #3: Building and testing

Translate design into a working product

Turning a concept into a product is where many teams stumble. Start by translating your problem statement and value proposition into user stories and features. Prioritise ruthlessly — focus on features that deliver the core value and leave nice‑to‑have items for later. Work with Engineering to plan delivery schedules and compromise where needed. Also consider technical feasibility and scalability. Over‑engineering early can slow you down, while under‑engineering can cause problems down the road. Choose architectures that allow you to adjust as you learn.

Test usability and gather feedback

User testing is not optional. Research by Jakob Nielsen shows that testing with five users can uncover about 85% of usability problems. This doesn’t mean you only test once. Run many small tests. Fix issues, iterate and test again. Use a mix of qualitative methods (moderated sessions, diary studies, beta programs) and quantitative methods (A/B tests, usage analytics). Slack’s early team followed this playbook: they invited six to ten companies to use Slack, learned how it behaved at different team sizes and iterated. They only opened up to larger groups once the product was polished. Adopting a similar pattern reduces the risk of widespread problems.

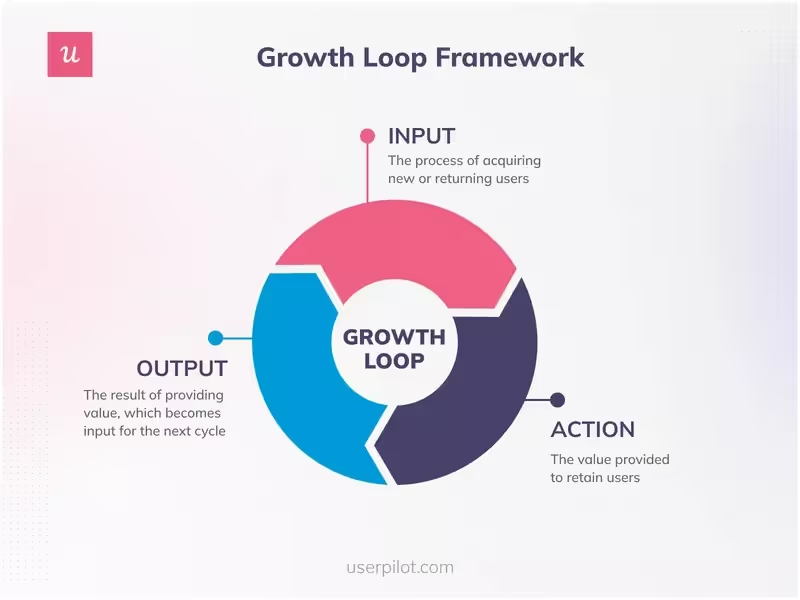

Define metrics and reach product‑market fit

Measure engagement, activation, retention and growth early. Signs of fit include high retention and organic growth. You should see users who would be genuinely upset if your product disappeared and a healthy balance between what it costs to acquire customers and what they are worth over time. Product‑market fit isn’t a switch but a spectrum. Keep measuring as you iterate because markets and expectations change.

Step #4: Launch, scale and sustain

Plan your go‑to‑market strategy

A great product still needs a thoughtful launch. Craft messaging that speaks to the problem you solve and why your solution is different. Identify the channels that reach your target audience — product‑led growth, content, partnerships or direct sales. Decide on pricing early; it signals value and informs your positioning. During the build process, continue to watch market conditions and be willing to change features, pricing or target users. When Slack launched, they avoided calling their preview a “beta” and leaned on their networks and press to build trust. The lesson: plan your launch months ahead, use whatever credibility you have and amplify your story through press and social channels.

Keep learning after launch

The work doesn’t end when you ship. Monitor usage, performance and satisfaction. Instrument your product to track time to value and retention, and collect feedback through support tickets, interviews and surveys. At Parallel we run monthly listening sessions with customers to understand evolving needs. Scaling doesn’t mean adding features indiscriminately; it means entering new markets or segments while maintaining quality. Keep testing: small experiments on pricing, onboarding and messaging reveal surprising insights. Stay alert to competitors and technological shifts. New technologies may change user expectations, so be prepared to experiment. This ongoing engagement with users is at the heart of how to create a great product.

Principles and best practices

Drawing from industry thought leaders and our own experience, here are principles to keep in mind:

- Solve the right problem. Spend more time understanding the problem than coding. Design thinking’s empathise and define stages reinforce this.

- Balance intuition and evidence. Use data to validate ideas, but allow room for creative leaps.

- Prioritise relentlessly. Focus on the few features that matter. Products That Count lists prioritisation as the first step to building great products.

- Stay close to users. Slack’s success stemmed from active listening and iteration. Engage with customers from discovery through launch and after.

- Iterate and learn. Run small experiments, test prototypes, measure results and adjust. Nielsen’s research on 5‑user tests shows how small studies can yield big insights.

- Define metrics and track them. Know what success looks like at each stage. Measure engagement, satisfaction and sustainability.

Case examples and lessons

Slack: feedback as the fuel for growth

Slack’s early story shows that centering on users drives success. The team invited a handful of companies to try Slack, learned how it behaved at different team sizes and iterated quickly. They deliberately avoided the word “beta,” called it a preview and used press and social proof to generate sign‑ups. The takeaway is simple: invite real users early, listen deeply, iterate and plan your launch to build trust.

Lessons from our practice

From our own projects we’ve seen two mistakes repeatedly: long sign‑up flows and ignored pricing. Simplifying onboarding to a few steps helps users start quickly. Testing price points early reveals who values your product and filters out those who won’t pay.

What Not to Do When Creating a Product

1. Don’t skip user research.

Assuming you understand the problem without talking to users leads to wasted work and wrong solutions.

2. Don’t build too much too soon.

Early over-engineering creates complexity before you’ve proven there’s demand. Start lean.

3. Don’t treat feedback as optional.

Collect input from users early and often. Product intuition without validation is risky.

4. Don’t copy competitors blindly.

Just because a feature works elsewhere doesn’t mean it fits your users or goals.

5. Don’t confuse features with value.

A long feature list doesn’t guarantee usefulness. Focus on solving the core problem well.

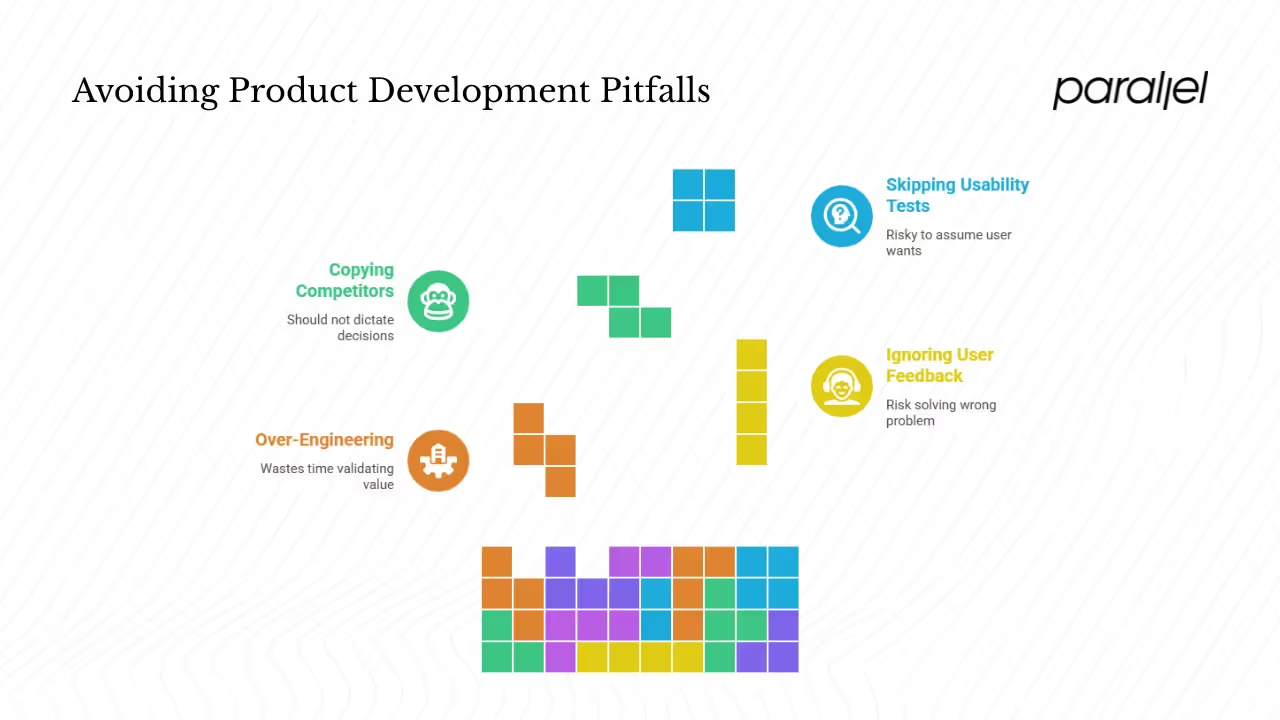

Challenges and common pitfalls

Creating a great product isn’t easy. Here are traps to watch for:

- Over‑engineering or premature optimisation. Building elaborate infrastructure before validating the core value wastes time.

- Ignoring or delaying user feedback. Without early feedback you risk solving the wrong problem. The five‑user rule from Jakob Nielsen’s research shows small tests can reveal most issues.

- Copying competitors. Competitive analysis informs decisions but should not dictate them.

- Skipping usability tests. Assuming you know what users want is risky; small tests reveal surprises.

Conclusion

Great products aren’t accidents. They start with understanding users and markets, move through ideation, prototyping, building and testing, and extend into launch and iteration. If you’re asking how to create a great product, start by listening to people and defining the problem. Build a simple version, test it with real users and track metrics that signal fit. Tell a clear story when you launch and stay close to your customers. Keep adjusting based on what you learn.

FAQ

1) What are the seven steps to create a new product?

One proven sequence is: discover and define the problem; conduct market and user research; generate and refine concepts; build a prototype or MVP; develop and test the product; launch; measure and iterate. Following these steps helps you answer how to create a great product by ensuring you validate each stage before moving on.

2) How do I create my own product?

Start with a clear user need. Research the market and potential users to validate that need. Design and prototype a solution, then put it in front of real users. Iterate based on feedback until the core value is clear. Develop the full product, launch it to your target audience, and continue to gather feedback and data to improve. This cycle captures how to create a great product in practice.

3) What are the three qualities of a good product?

- Solves a real need. It addresses an important job in the user’s life.

- Usable and pleasant. It feels intuitive and enjoyable, with usability proven through testing.

- Feasible and sustainable. It can be built and maintained with available resources, and the business model works.

4) How can I create a unique product?

Look for needs that are underserved or unserved. Conduct market and competitive analysis to find gaps. Differentiate through your value proposition, design or experience. Innovation can come from technology, business models or the way you deliver value. Above all, stay close to users; they will tell you where your product shines and where it falls short. That’s the heart of how to create a great product.

.avif)