How to Write an Epic in Agile: Complete Guide (2026)

Discover how to write effective epics in agile development, including defining user value, acceptance criteria, and prioritization.

If you’re building a product from scratch, you’ve likely encountered big, ambitious goals with no clear next step. A founder might ask the team to “deliver onboarding for our new AI product,” but without structure the work feels overwhelming. Early‑stage teams usually don’t have the luxury of layers of specialists; they need a simple way to connect a high‑level vision to day‑to‑day tasks. This article answers one question: how to write an epic in agile so that a lean team can turn fuzzy ambition into actionable work. Written from firsthand experience supporting early‑stage SaaS startups, it explains what an epic is, when to create one, how to write one, how to break it down and track progress, and ends with examples, tips and a FAQ.

What is Agile?

Agile is an iterative approach to product development rather than a rigid linear process. Asana’s 2025 guide describes agile as a project‑management framework that breaks projects into dynamic phases called sprints and encourages teams to reflect after each sprint to adapt their strategy. The approach is grounded in the values of the Agile Manifesto—individuals over processes, working software over documentation, customer collaboration over contract negotiation, and responding to change over following a plan. Twelve supporting principles encourage frequent delivery, welcoming changing requirements, cross‑functional collaboration and continuous reflection.

At its core, agile emphasises small increments of value delivered often. Breaking work down into smaller pieces makes it easier to adapt to change and learn from customer feedback. Agile methods like Scrum, Kanban and Extreme Programming share this philosophy of iterative, incremental delivery.

Why breaking down work matters in agile

Projects rarely fit neatly into a single sprint. To stay adaptable, teams must break big work into smaller slices that can be delivered and tested quickly. This reduces risk, increases feedback loops and ensures progress is visible to the team and stakeholders. As we'll see, epics provide a way to group related user stories under a common goal, bridging the gap between a strategic vision and actionable tasks.

Epics in the agile framework

An epic is a large body of work that can be broken down into a number of smaller stories or tasks. Atlassian defines an agile epic as a collection of specific tasks (called user stories) based on the needs or requests of customers or end‑users. The Adobe Experience Cloud team adds that epics are usually too big to be completed within a single sprint and provide a high‑level view of your project, keeping the focus on the main strategic goal. Because an epic contains many user stories, it spans multiple sprints and often involves several teams or disciplines.

Epics sit within a hierarchy:

Epic vs. user story

A story is something a team can commit to finish within a one‑ or two‑week sprint. Stories are numerous; a team might complete dozens in a month. Epics, by contrast, are few in number and take longer. Teams often work on two or three epics over a quarter. Where a story tells one small narrative, an epic ties several related stories together to capture the broader objective. Stories represent the arc of work completed, while the epic provides the high‑level view of the unifying objective. Understanding this distinction is vital because writing good epics sets the stage for efficient planning, prioritisation and collaboration.

Why writing good epics matters (especially for lean teams)

For early‑stage startups, well‑written epics provide several advantages. Learning how to write an epic in agile equips teams with a repeatable approach to organise work:

- Alignment of vision and execution: By explicitly connecting user stories to a broader goal, epics ensure designers, developers and stakeholders share a common understanding of “why we’re doing this.” The Adobe guide emphasises that epics link strategic initiatives with actionable stories.

- Prioritisation and planning: A clear epic helps teams sequence user stories by value, risk or dependencies. Businessmap’s State of Agile statistics show that 32% of agile practitioners link Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) to epics for executive‑level delivery measurement, highlighting their importance for strategic alignment.

- Stakeholder communication: Epics serve as a single source of truth for what is in scope, the assumptions and success measures. When handing off work to engineers or designers, the epic narrative reduces ambiguity and prevents misalignment.

- Incremental delivery: By decomposing an epic into vertical slices, teams can deliver value sooner, gather feedback and adjust the epic’s scope—key to agile adaptability.

When to create an epic — triggers and signals

Knowing when to group work into an epic is as important as knowing how to write one. In practice, several triggers indicate that creating an epic is beneficial:

- Large features or domains: When a requirement is clearly too big for a single sprint (e.g., building a multi‑step onboarding flow), grouping related stories under an epic provides structure.

- Multiple related stories with a common goal: If you have a set of user stories that share the same objective—such as improving search performance on a platform—creating an epic clarifies that these stories contribute to one outcome.

- Stakeholder requests or strategy changes: When business stakeholders add a new strategic initiative (e.g., “expand into the US market”), a defined epic helps the team turn that high‑level goal into actionable work.

- Outcomes of product discovery, research or OKRs: Discovery workshops often identify problem spaces rather than discrete features. Converting these into epics ensures that insights from user interviews and competitive audits feed directly into the backlog. Businessmap notes that linking OKRs to epics is gaining popularity, with a 5% increase since 2022.

When you understand how to write an epic in agile, it becomes easier to spot these triggers and structure work accordingly. Teams who master this skill can confidently say “this is big enough to be an epic” rather than letting large goals float around as vague to‑dos.

Epics should be flexible. Atlassian emphasises that scope changes are a normal consequence of agile development, and as teams progress through an epic they may take on or remove work based on learning. Creating epics early and revisiting them throughout execution helps manage this flexibility.

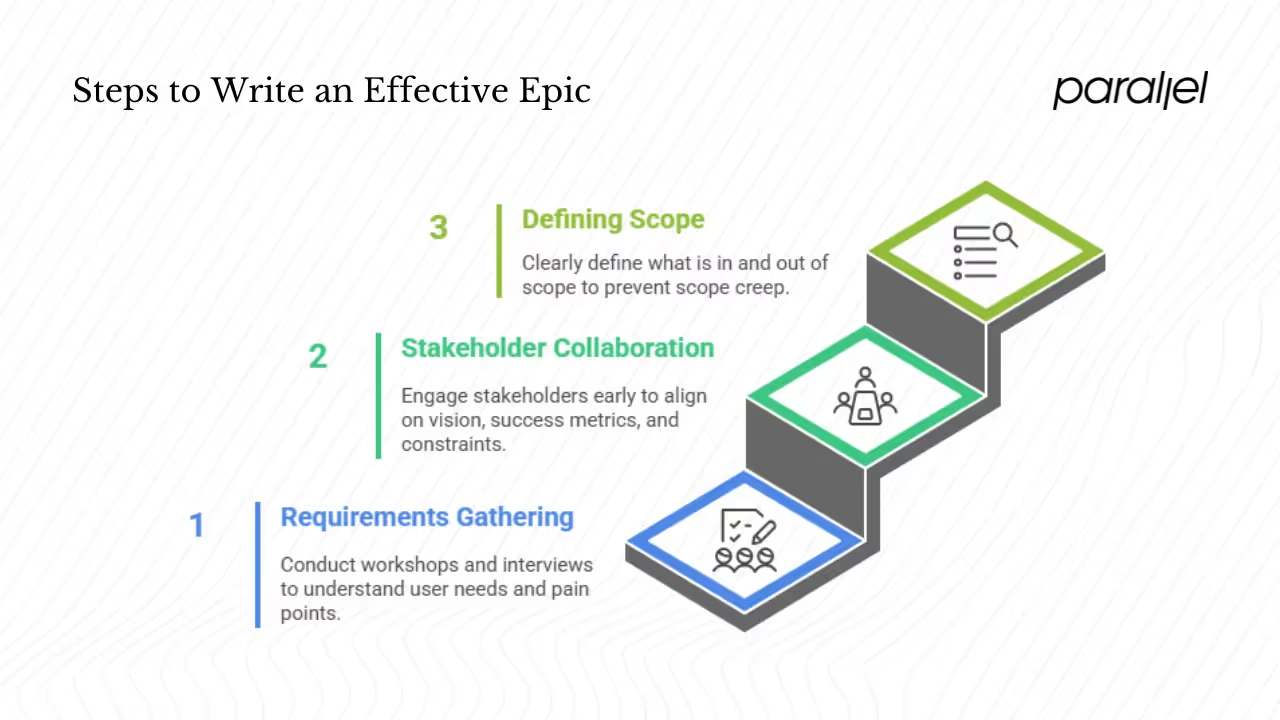

Pre‑epic work: inputs and collaborations

Writing a good epic requires preparation. Before opening a ticket in your project management tool, spend time gathering requirements, aligning stakeholders and defining scope.

1) Requirements gathering & discovery

Agile emphasises conversation over documentation, but that doesn’t mean skipping discovery. Nielsen Norman Group describes user‑story mapping as a lean UX method that uses sticky notes and sketches to outline the interactions users go through to complete their goals. Story maps replace lengthy requirements documents and foster collaboration. Before writing an epic you must know how to write an epic in agile:

- Run discovery workshops: Bring together product, design, engineering and business stakeholders to discuss the problem space. Identify user pain points, desired outcomes and success measures.

- Conduct user interviews: Talk to potential customers to understand needs and behaviours. Keep your interview questions open‑ended and avoid leading participants.

- Audit competitors and analogous products: Look at how others solve similar problems; this inspires ideas and reveals opportunities.

- Use visual frameworks: Tools like opportunity solution trees and impact mapping help translate stakeholder needs into problem spaces and candidate solutions.

2) Stakeholder collaboration & alignment

Engage stakeholders early. Agile values customer collaboration and responding to change; that requires conversation. Bring business owners, design, engineering and QA into the epic creation process to align on key elements of the epic:

- Vision: What problem are we trying to solve? How does this epic support company objectives?

- Success metrics: How will we know the epic delivered value? Define outcome metrics (e.g., “reduce onboarding drop‑off from 50% to 20%”) rather than only output metrics.

- Constraints: Note regulatory requirements, technical constraints and external dependencies.

Alignment reduces rework later and surfaces differing assumptions early. Asana’s principles emphasise that the most effective way to communicate is face‑to‑face. In remote contexts, replicate this with video calls or workshops.

3) Defining scope & boundaries

Scope clarity prevents endless epics. Define what is in scope (features, user journeys, markets) and what is out of scope. Consider milestones, release windows and constraints. Beware of scope creep, but allow room to adjust when learning. Agile emphasises welcoming changing requirements even late in development; balancing this adaptability with clear boundaries keeps the team focused.

Document explicit non‑goals—aspects you will not address within this epic. This gives stakeholders confidence that you have thought about trade‑offs and prevents pet requests from diluting focus. Teams that understand how to write an epic in agile know that identifying non‑goals is just as important as listing features.

Writing the epic — structure & format

A well‑written epic is concise yet descriptive. It should read like a story, not a specification. Here is a suggested structure:

- Title: A short, descriptive name. Avoid jargon; summarise the outcome (e.g., “Streamlined onboarding for new customers”).

- Narrative: A brief description of the goal or outcome the epic drives. State the user or business problem and the value of solving it. For example: “Customers sign up for our AI‑powered analytics tool but drop off during onboarding. We want to reduce drop‑off by providing a simpler, guided onboarding experience.”

- Context & assumptions: Include any relevant business rules, dependencies or assumptions. Note existing systems affected or prerequisites.

- Success metrics / measures: Define how you’ll know the epic is complete. Use metrics like adoption, activation rate, time‑to‑value or revenue impact.

- Stakeholders & roles: Identify who owns the epic (e.g., product manager), who is involved (design lead, tech lead, QA), and key external stakeholders.

- Constraints & non‑goals: Document regulatory constraints, technical limitations and explicit exclusions.

- Acceptance criteria (high level): At the epic level, acceptance criteria are broad. They might state that a customer can complete onboarding without support or that the service meets performance SLAs. Adobe’s best practices recommend establishing acceptance criteria and defining clear objectives for each epic.

- References: Link research, personas, OKRs or discovery outputs.

Template suggestions

Many teams use an “Epic Card” pattern inspired by user stories: “As a [user], I want [goal], so that [value].” Adapt this at the epic level. For example: “As a new customer, I want a guided setup process so that I can start using the product without confusion.” Expand the narrative below to include context, success measures and constraints.

The INVEST acronym—Independent, Negotiable, Valuable, Estimable, Small, Testable—applies mostly to user stories. However, epics can adopt a similar mindset. Ensure they deliver value, are negotiable as new information emerges, and are testable through well‑defined success metrics and acceptance criteria. When coaching teams on how to write an epic in agile, emphasise that even high‑level work must be testable and adjustable.

Making it actionable

Write the epic as if handing it to someone who has not been part of the discovery sessions. Keep it high level—avoid technical implementation details—but include enough context that the team can break it down without guessing. Good epics are like mini‑stories: they outline the protagonist (user), problem, and desired outcome.

Atlassian reminds us that epics often encompass multiple teams and boards and may be tracked across several projects. Therefore, clarity and traceability are vital. Use your tool’s epic fields (Jira, Wrike, Monday.com) to capture the structure above. In Jira, epics have their own issue type and color; linking stories to the epic ensures traceability.

Decomposition: from epic → stories

An epic is only valuable if you can break it down. Decomposition turns strategy into deliverables.

Story mapping & backlog decomposition

Instead of writing a long list of tasks, story mapping visualises the customer journey. Nielsen Norman Group explains that a user‑story map depicts activities (high‑level tasks), steps and details. Activities and steps run horizontally, showing the sequence of user actions, while details stack vertically in priority order. Using this method to break epics into user stories has several benefits:

- It keeps the user journey front and centre, preventing the team from losing sight of the product as a whole.

- It helps teams identify vertical slices—end‑to‑end features that deliver value to users—rather than horizontal layers (like front‑end only or database only). Vertical slices ensure each story is independently valuable and testable.

- It encourages collaboration and conversation, as team members collectively sketch the map and agree on priorities.

After creating a story map, decide which slices to build first. Include at least one story per main activity so users can complete a simple journey. Save lower‑priority details for later iterations.

Story decomposition techniques

When splitting an epic into stories, consider the following approaches:

- Workflow slicing: Break work by CRUD operations (create, read, update, delete). For example, for a user profile epic, one story covers “view profile,” another “edit profile,” etc.

- User personas or states: Split by different user roles or lifecycle stages. For a marketplace epic, write separate stories for buyers and sellers or for first‑time versus returning users.

- Happy, unhappy and edge paths: Identify the primary “happy” path first, then write stories for error handling, edge cases or performance improvements.

- Performance, UI, backend, data: Sometimes splitting by technical layer makes sense, especially for early spikes. However, avoid creating purely technical stories; tie each to user value.

- Spikes or research stories: When unknowns are high (e.g., exploring a third‑party API), create a time‑boxed research story to gather information and reduce risk. Spikes do not deliver user value directly but inform subsequent stories.

Use prioritisation frameworks to order stories. Methods like MoSCoW (Must‑Should‑Could‑Won’t), RICE (Reach, Impact, Confidence, Effort), ICE (Impact, Confidence, Ease), or WSJF (Weighted Shortest Job First) help quantify value versus effort. Businessmap’s research shows that engineering and R&D teams are the fastest‑growing adopters of agile, comprising 48% of practitioners; these teams often use structured prioritisation to manage scarce resources.

Once you’ve split the epic, maintain linkage between stories and the epic in your tool. This ensures traceability and enables progress tracking. A crucial part of how to write an epic in agile is recognising that decomposition doesn’t end after the initial split; epics evolve as you learn.

Planning & execution of the epic

Iteration and sprint planning

Inject epic stories into sprint planning based on capacity and priority. In Scrum, a sprint backlog is built from the top of the product backlog. Include stories from multiple epics if needed but be transparent about which epic each story belongs to. Resist the urge to finish an entire epic before shipping value; deliver slices early to gather feedback.

Roadmap planning

Map epics to releases or increments. For instance, if your epic spans three sprints, plan to deliver the most critical stories in the first sprint so stakeholders see progress. Use release planning to communicate which epic goals will be achieved by each release.

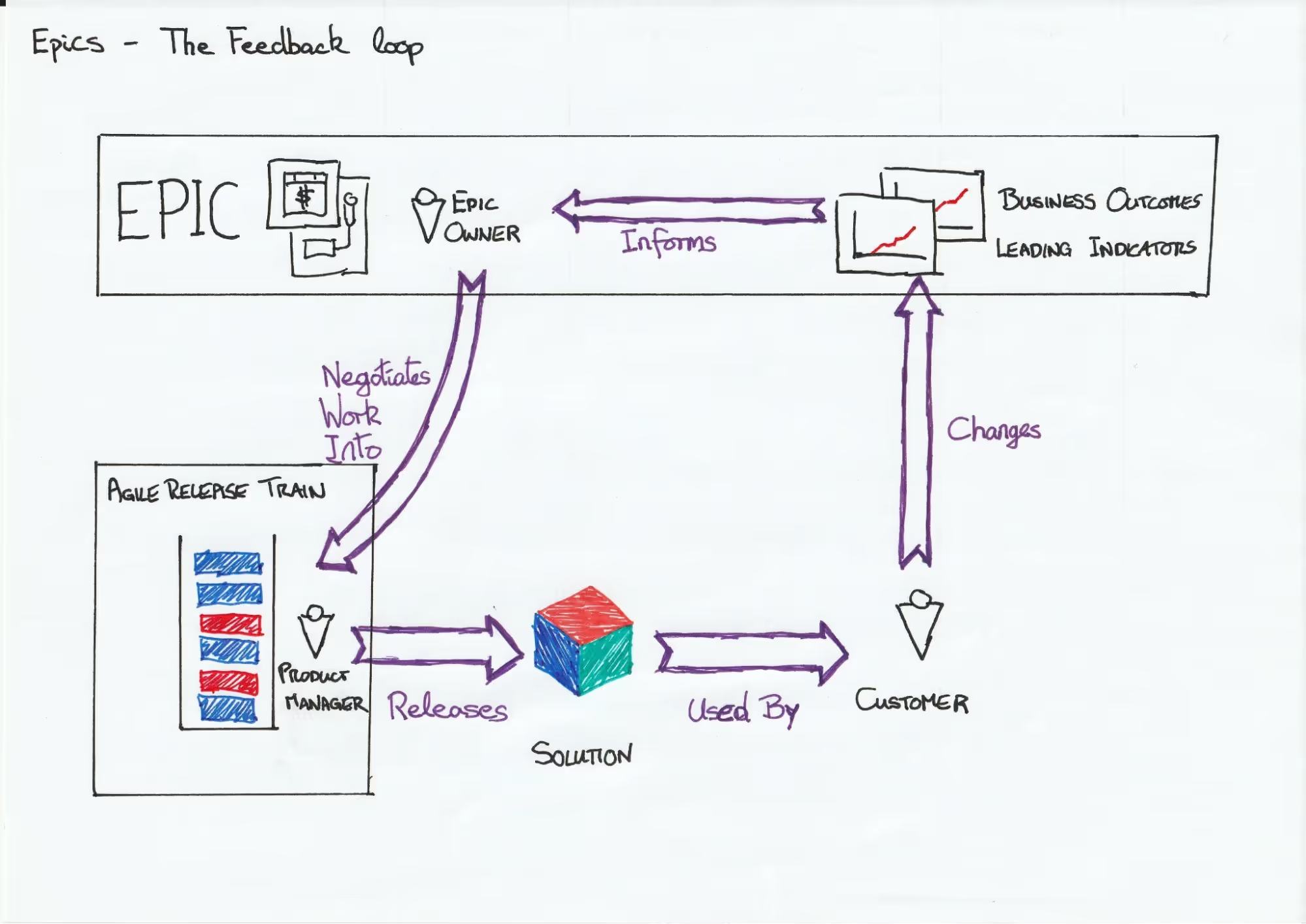

Progress tracking & metrics

Agile metrics help you monitor the epic’s progress and identify issues early. Epic and release burndown charts track the progress of development over a larger body of work than sprint burndown and guide development for both Scrum and Kanban teams. Since a sprint may contain work from several epics, it’s important to track progress across individual sprints as well as epics and versions. These charts also make “scope creep” visible: when the burndown line stalls or moves upward, the team can discuss scope changes.

Other useful metrics include:

- Velocity: Average number of story points completed per sprint. Use it to forecast future sprints but avoid weaponising it; velocity is a planning tool, not a performance metric.

- Cycle time and throughput: Track how long it takes to complete stories and how many stories are delivered per sprint. Long cycle times can indicate bottlenecks.

- Cumulative flow diagrams: Visualise work in different stages (to do, in progress, done) to spot work‑in‑progress issues.

Businessmap’s 2025 statistics reveal that 39% of respondents using agile report the highest average project performance (75.4% success). Monitoring metrics like epic burndown helps teams maintain high performance.

Handling changes & pivots mid‑epic

Agile embraces change, but unmanaged change can derail a team. When new information emerges:

- Revisit assumptions and scope. If an experiment invalidates part of the epic, update or remove related stories. Document why to preserve context.

- Trim or postpone lower‑priority stories. Use prioritisation frameworks to decide which slices can move to later releases.

- Replan the next slices with new knowledge. Adjust the story map or backlog; maybe a story previously considered essential is no longer needed.

- Communicate transparently. Explain changes to stakeholders. The agile principle of customer collaboration encourages open communication.

Tools & best practices

Project management tools & setups

- Jira: Provides native epic issue types, story linking, boards and backlog. The epic burndown chart makes progress visible. Use labels or components for themes and initiatives.

- Wrike: Wrike’s epic guide notes that epics are a collection of user stories and may span multiple teams. Wrike templates include backlog boards and interactive sprints that help visualise epics and stories.

- Monday.com / Notion / ClickUp: These tools support custom item types; create an “Epic” type with fields for narrative, metrics, stakeholders and acceptance criteria. Use dashboards or roll‑up fields to track progress across stories.

- Plugins & extensions: Tools like Roadmaps (Jira Advanced Roadmaps), Portfolio for JIRA or third‑party plugins provide roll‑up estimations and epic‑to‑initiative hierarchies.

Choose a tool that fits your team size and maturity. The tool should allow linking stories to epics, visualising progress, and customising fields for your epic template.

Collaboration rituals & alignment

- Epic kick‑off / inception session: When starting an epic, bring the team together to review the narrative, assumptions, success metrics and story map. Align on priorities and dependencies. These sessions mirror design studios and emphasise co‑ownership.

- Regular check‑ins: Hold weekly or biweekly check‑ins to review progress, update the story map and adjust scope. Use burndown charts or dashboards for visibility.

- Backlog grooming: Set aside time each week to refine epic stories. Split large stories, clarify acceptance criteria, and prioritise slices for upcoming sprints.

- Demos & reviews: At the end of each sprint, demo slices related to the epic to stakeholders. Gather feedback and decide on adjustments. This practice aligns with Asana’s principle of customer collaboration and frequent delivery.

Pitfalls & anti‑patterns to avoid

- Vague or abstract epics: Avoid epics with no clear outcome or success measure. Without a defined goal, decomposition and prioritisation become guesswork.

- Over‑engineering details: Resist the urge to include technical implementation details in the epic. High‑level assumptions are fine; details belong to stories or tasks.

- Uncontrolled scope creep: Write explicit non‑goals and check them during grooming. Use burndown charts to visualise scope additions.

- Losing traceability: Always link stories to their epics. Without linking, progress is invisible and metrics are meaningless.

- Waiting for the entire epic to finish before shipping value: Agile emphasises incremental delivery. Release vertical slices early even if the full epic is incomplete.

Examples & case studies

Example of a well‑written epic

Epic: Streamlined onboarding for our analytics platform

Narrative: New customers frequently drop off during onboarding. We aim to deliver a simple, guided onboarding experience that reduces drop‑off from 50% to 20% and decreases time‑to‑first‑value to under five minutes.

Context & assumptions: Our analytics tool currently requires users to connect multiple data sources manually. We assume we can build a connector for the most common source (e.g., Google Analytics) and a guided flow for the rest. We also assume that adding a progress indicator will help users understand how long setup takes.

Success metrics: Activation rate (users who complete onboarding and run a report) increases from 40% to 70%. Drop‑off rate decreases from 50% to 20%. Average setup time decreases to five minutes.

Stakeholders & roles: Product manager (owner), design lead, tech lead, QA lead, marketing representative. Stakeholders include customer success and support teams.

Constraints & non‑goals: We will not support custom enterprise data connectors in this epic. Performance improvements to the reporting engine are out of scope. Regulatory compliance (GDPR) must be maintained.

High‑level acceptance criteria:

- A new customer can sign up, connect their primary data source, and run their first report without contacting support.

- Progress is saved at each step so users can return later without losing work.

- The onboarding flow meets our accessibility guidelines and loads within two seconds on average.

Decomposition (vertical slices):

- Build sign‑up flow with email/password and social login.

- Create data‑source connector for Google Analytics.

- Implement guided UI with progress indicator and tooltips.

- Add in‑app checklist and success messaging.

- Measure activation rate and adjust content based on feedback.

Good vs. bad epics

The refined epic turns an ambiguous request into an actionable plan. It links directly to business outcomes, defines success, and sets clear boundaries.

Real‑world cases

Marketing campaign epic: Adobe’s 2025 guide provides an example of launching a major marketing campaign to boost SaaS subscriptions by 25%. The campaign’s epics include “Plan the marketing campaign,” “Deliver the campaign,” and “Measure results”. Each of these epics is further broken down into user stories such as identifying target audiences, preparing assets and tracking metrics, illustrating how a strategic goal becomes multiple epics and stories.

Cross‑functional adoption: Businessmap’s statistics show that agile adoption is expanding beyond software teams—48% of agile practitioners are now engineering or R&D teams, and 86% of marketers plan to shift some or all of their teams to agile. These numbers highlight how epics are no longer limited to software projects; marketing, HR and operations teams are writing epics for campaigns, talent onboarding and process improvements.

Wedding reception epic: Wrike’s guide offers a non‑software example: organising a wedding reception for 50 guests. The epic includes user stories such as picking a venue within a locality, preparing food to suit dietary requirements, selecting decorations to match the theme and booking a live band. A product owner (in this case, a wedding planner) ensures the user stories satisfy the clients’ needs. This example demonstrates that the epic/story approach applies to physical events as well as software.

When to close an epic & retrospect

An epic is complete when all its stories are done and the success metrics are met. Evaluate whether the epic’s outcome delivered the intended value. Hold an epic retrospective to discuss what worked, what didn’t and what to improve next time. Asana’s agile principles emphasise regularly reflecting and adjusting to improve effectiveness. Archive the epic, link it to the initiative or OKR it supported, and convert leftover items into new stories or epics. Use learning to improve your next epic.

Conclusion

Epics are the connective tissue between strategy and execution. They translate high‑level goals into collections of user stories, align teams around a shared vision and provide a roadmap for incremental value delivery. To recap the process:

- Define: Use discovery workshops and user research to identify the problem, context and success metrics. Align stakeholders on vision and constraints.

- Write: Craft a concise narrative, define scope and non‑goals, list stakeholders, success measures and high‑level acceptance criteria. Structure the epic like a story and avoid technical details.

- Decompose: Create a user‑story map, split the epic into vertical slices and prioritise using frameworks like MoSCoW or RICE.

- Plan & track: Inject stories into sprints, map epics to releases, track progress with epic burndown charts and adjust scope as you learn.

- Close & reflect: When all stories are done and metrics met, close the epic, run a retrospective and carry lessons forward.

Writing good epics is both an art and a discipline. With practice, your team will learn how to write an epic in agile that bridges vision and execution. The result is a shared understanding of what matters, faster delivery of customer value, and a more resilient product development process.

FAQ

1) What is an example of an epic in agile?

An epic is a large piece of work that groups related user stories. Domain‑agnostic examples include:

- Onboarding flow for new users: The epic might aim to reduce drop‑off by guiding new customers through sign‑up, data import and first value. Stories include building sign‑up, data connectors, tutorials and success messaging.

- Migration from monolith to microservices: The epic could involve decomposing a legacy system into microservices. Stories might cover extracting authentication, creating APIs, setting up CI/CD and migrating data.

- Company‑wide rebranding: This epic would coordinate design, content, marketing and engineering to update logos, UI themes and marketing materials. Stories could include updating the website header, refreshing email templates and creating new brand guidelines.

2) How should an epic be written?

A good epic includes a clear title, a short narrative describing the problem and the desired outcome, context and assumptions, success metrics, stakeholder roles, constraints, non‑goals and high‑level acceptance criteria. It should be framed from the user or business perspective and avoid technical implementation details. Adobe recommends defining clear objectives, establishing acceptance criteria, breaking the epic into user stories, prioritising effectively, estimating effort, visualising progress and continuously gathering feedback.

3) What is the best example of an epic?

There is no single “best” epic—quality is context‑dependent. The marketing‑campaign example from Adobe’s 2025 guide is illustrative: the organisation wanted to boost SaaS subscriptions by 25%. They defined three epics—planning the campaign, delivering it and measuring results—and broke each into user stories. Success metrics were clear, scope was bounded and stories were linked to user outcomes. This structure makes it a strong example.

4) What is the format of an epic?

The format varies by organisation, but a typical epic includes:

- Title: Concise, outcome‑oriented name.

- Narrative/Description: Problem statement and goal.

- Context and assumptions: Business rules, dependencies, current pain points.

- Success metrics: How success will be measured (e.g., adoption rate, revenue impact).

- Stakeholders and roles: Owner and participants.

- Constraints and non‑goals: What is out of scope.

- High‑level acceptance criteria: Conditions that must be met for the epic to be considered done.

Many teams adapt the “As a [user], I want [goal], so that [value]” pattern for the epic narrative, followed by detailed fields in their project management tool. Wrike summarises the hierarchy as user story < epic < initiative < theme, emphasising that an epic groups related stories and may span multiple teams and sprints.

.avif)