How to Write Product Requirements: Complete Guide (2026)

Discover how to write clear product requirements documents (PRDs) that align teams, define scope, and guide successful development.

Writing product requirements isn't glamorous, but it's one of the highest‑leverage activities in product development. Misalignment around requirements leads to rework, wasted development effort and missed opportunities.

A 2025 Carnegie Mellon Software Engineering Institute study found that 60–80% of software development cost goes into rework and that effective requirements management can eliminate 50–80% of project defects. As a founder and product person at Parallel, I've watched teams waste weeks clarifying vague requirements—vague requirements lead to misalignment, rework and delays.

This article lays out a pragmatic, step‑by‑step structure for how to write product requirements effectively. You'll see concrete examples, pitfalls to avoid and insights from our work with early‑stage AI/SaaS teams.

What are product requirements and why they matter

Product requirements describe what a product must do and the conditions it must satisfy. They focus on outcomes rather than solutions—the “what” and “why,” not the “how.” A product requirements document (PRD) translates customer needs into a clear list of features and user experiences. It acts as a reference point for designers, engineers and stakeholders. Functional requirements capture specific behaviours (e.g., the system sends a password reset email when a user requests it), while non-functional requirements define performance, security, usability, reliability and other quality attributes. Business, regulatory, interface and data requirements may also be captured.

Well‑written requirements align stakeholders, reduce ambiguity and serve as a contract throughout the product life cycle. Without clarity, scope creep and rework abound. Studies show developers spend roughly 35% of their time on non‑coding tasks such as clarifying requirements; poor traceability forces costly test cycles and late fixes. Good requirements counter these inefficiencies by providing a shared understanding of what success looks like.

The role of PRDs in agile vs. waterfall

In agile environments, lightweight PRDs evolve alongside the product. User stories and acceptance criteria may live in issue trackers like Jira and serve as the living specification. In waterfall or regulated industries, a more formal PRD or functional specification is often required upfront to control scope and support compliance. Hybrid approaches combine a PRD for high‑level context with detailed user stories and prototypes for iterative development.

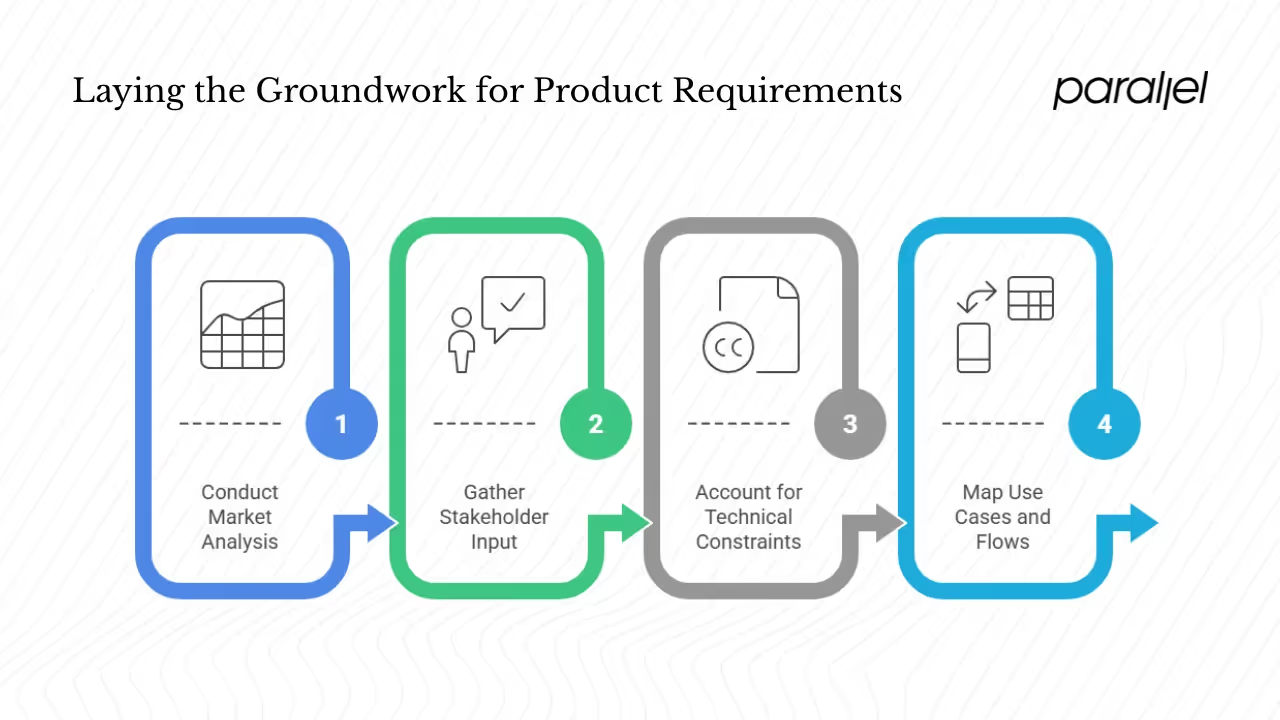

Step #1: Lay the groundwork before writing

1) Conduct market analysis and competitor benchmarking

Strong requirements start with context. Market research blends consumer behaviour with economic trends to validate and improve your business idea. Understanding your target market reduces risk and helps you identify opportunities and limitations. Ask questions about demand, market size, economic indicators and pricing. Competitive analysis pinpoints existing products’ strengths, weaknesses and market share. At Parallel, we often benchmark competitor workflows and performance to find differentiation—for example, noticing that competitor onboarding flows require four screens and adding friction, we wrote requirements to reduce onboarding steps to two and cut time‑to‑value by 30 %.

Understanding market gaps and competitor positioning is essential for how to write product requirements that differentiate your product without reinventing the wheel.

2) Gather stakeholder input and user needs

Stakeholders include customers, internal teams (marketing, support, sales), domain experts and regulators. Interviewing them uncovers pain points, constraints and aspirations. Distinguish needs (problems that must be solved) from wants (nice‑to‑haves). Use techniques like one‑on‑one interviews, usability studies and surveys. Synthesize recurring themes into user insights; avoid letting a single vocal stakeholder skew requirements. At Parallel we've seen early‑stage founders over‑index on investor feedback, only to build features users didn’t need.

Identifying true user needs versus superficial desires is a core lesson in how to write product requirements that focus your team on real value.

3) Account for technical constraints and assumptions

Document platform or architectural constraints (e.g., mobile only, integration with a legacy CRM, third‑party APIs). Note dependencies, such as data feeds or payment gateways. Define resource constraints—budget, timeline, team capacity—and make assumptions explicit so future readers can revisit them. For instance, if your requirement assumes a stable internet connection, call it out.

4) Map use cases and flows

Use cases illustrate how actors interact with your system to achieve goals. A use case includes actors, system, goals, preconditions, triggers, basic flow, alternative flows and post‑conditions. For example, in an ecommerce use case the customer selects products, adds them to the cart, proceeds to checkout and receives a confirmation; alternative flows capture exceptions like insufficient funds. Mapping these flows clarifies system boundaries and helps identify edge cases before writing requirements. Our team often uses tabular use case templates for clarity.

Step #2: Structure your product requirements document

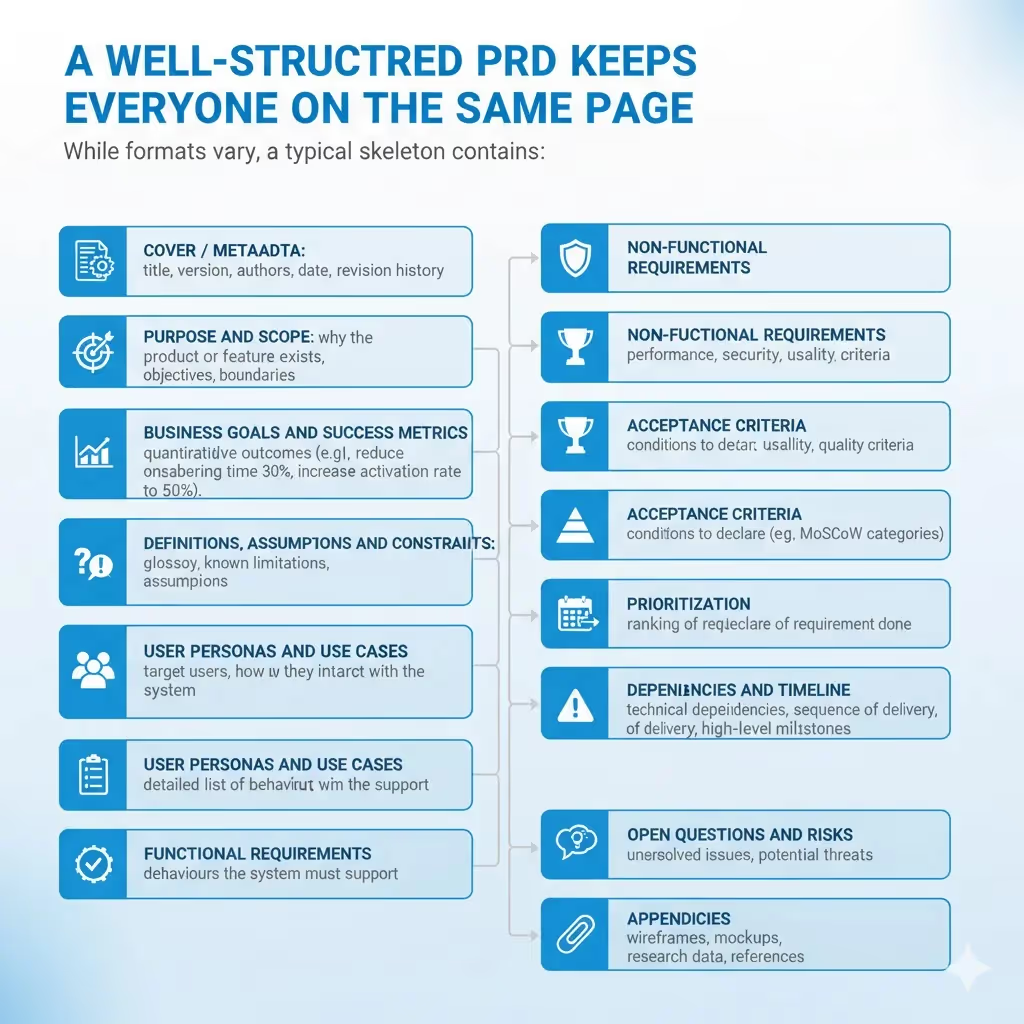

When you're learning how to write product requirements, starting with a clear structure is key.

A well‑structured PRD keeps everyone on the same page. While formats vary, a typical skeleton contains:

- Cover / metadata: title, version, authors, date, and revision history.

- Purpose and scope: why the product or feature exists, its objectives and its boundaries.

- Business goals and success metrics: the quantitative outcomes that matter (e.g., reduce onboarding time by 30 %, increase activation rate to 50 %).

- Definitions, assumptions and constraints: glossary of terms, known limitations and assumptions.

- User personas and use cases: who the target users are and how they will interact with the system.

- Functional requirements: detailed list of behaviours the system must support.

- Non‑functional requirements: performance, security, usability and other quality criteria.

- Acceptance criteria: conditions to declare a requirement done.

- Prioritization: ranking of requirements (e.g., MoSCoW categories).

- Dependencies and timeline: technical dependencies, sequence of delivery and high‑level milestones.

- Open questions and risks: unresolved issues and potential threats.

- Appendices: wireframes, mockups, research data and references.

The Altexsoft PRD guide notes that the PRD translates customer needs into functionality and serves as a core document alongside market (MRD), business (BRD) and software requirements documents (SRD). An SRD focuses on technical specifications and non-functional requirements; understanding this hierarchy helps avoid mixing solution design into requirements.

For lightweight agile contexts, keep the PRD focused on the problem, user stories and key non‑functional requirements. Heavyweight contexts (e.g., medical devices) demand detailed sections to satisfy compliance. Hybrid approaches pair a concise PRD with evolving user stories, prototypes and acceptance tests.

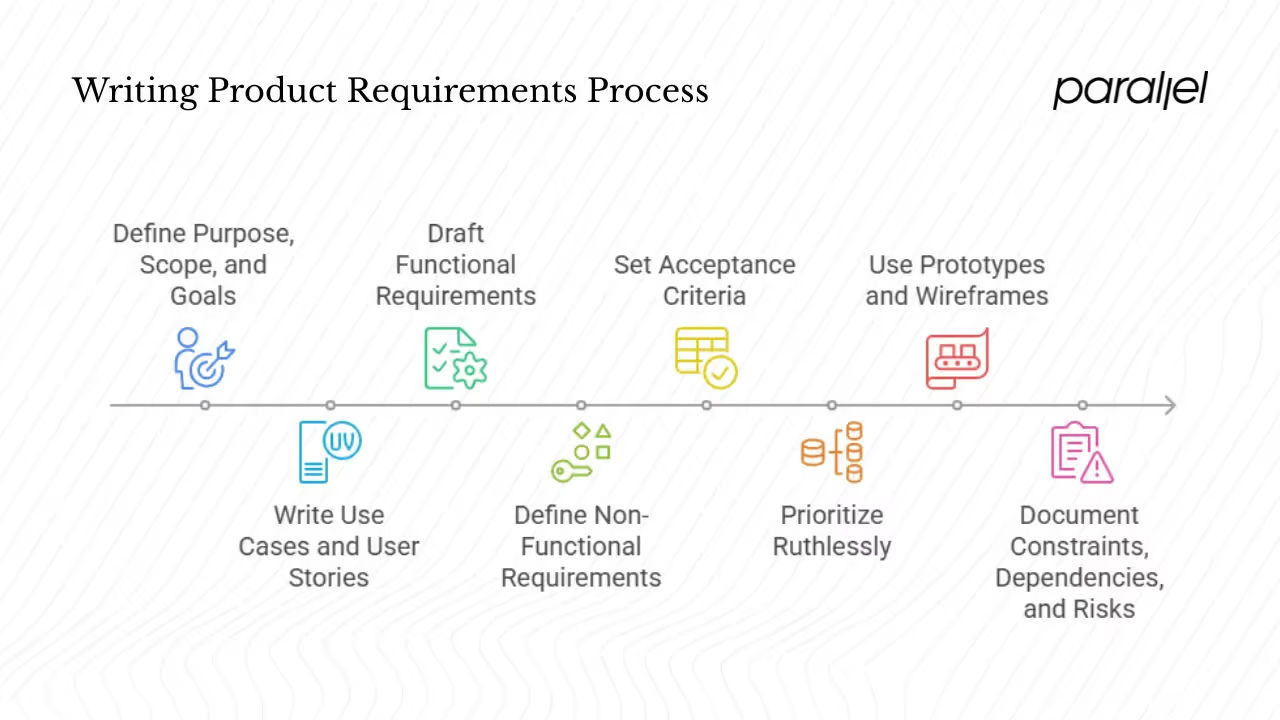

Step #3: Write each section in depth

The following sections break down how to write product requirements that are clear, testable and aligned with user value.

1) Define purpose, scope and goals

Begin with a clear problem statement: what pain are you solving and for whom? Identify your target audience or personas. Articulate business goals and success metrics—quantitative targets that measure impact. For example: “Reduce the average onboarding time from 5 minutes to 3 minutes by Q2 2026” or “Achieve a 50 % activation rate within the first week.” Clear goals align the team and enable testability.

2) Write use cases and user stories

Use cases describe sequences of interactions; user stories express requirements from the user’s perspective. A common template is: As a [user], I want [goal], so that [benefit]. Tie each user story back to a use case to maintain traceability. For example: “As an unauthenticated user, I want to reset my password so that I can regain access.” Each story should include acceptance criteria and priority.

3) Draft functional requirements

Functional requirements specify what the system must do, not how it should be built. Make them clear, specific and testable. Avoid ambiguous language like “etc.” or “and so on.” Break complex features into epics and sub‑features. Link each requirement to its origin (user story or business need) and maintain traceability through design, development and testing. For instance:

- Requirement: When a user enters a valid email and password, the system shall authenticate them and redirect to the dashboard.

- Traceability: Tied to user story “As a returning user, I want to log in so that I can access my data.”

4) Define non‑functional requirements (NFRs)

NFRs capture how well the system should perform. According to Perforce’s 2025 guide, non‑functional requirements specify criteria such as performance, security, usability, reliability and scalability. They act as quality goals or constraints for functional requirements.

Consider the following categories and examples:

- Performance and scalability: The system shall respond to user actions within 200 ms under a load of 1,000 concurrent users. It must handle 50,000 monthly active users without degradation.

- Security: Requirements addressing data protection, threat resistance and encryption. Example: All sensitive data shall be encrypted at rest using AES‑256.

- Reliability and availability: Define acceptable downtime and fault tolerance. For example: 99.9 % uptime during business hours; no data loss on server failure.

- Usability: Criteria for interface accessibility, localization and accessibility. For example: The checkout process must be completable using a keyboard and screen reader.

- Compliance: Industry or legal requirements, such as HIPAA or GDPR.

- Maintainability and monitoring: Requirements for log retention, observability and modular code design.

Prioritize NFRs alongside functional features. Ignoring them leads to slow, unreliable products and user dissatisfaction.

5) Set acceptance criteria

Acceptance criteria define conditions under which a requirement or user story is considered complete. They make expectations explicit and serve as the basis for testing. Many teams use the Given–When–Then format, borrowed from Behaviour‑Driven Development (BDD). For example, Nimble’s AI platform illustrates password reset acceptance criteria: Given a user clicks “Forgot Password,” When they enter a registered email, Then they receive a one‑time password within 2 minutes. Each criterion should be testable and binary (pass/fail). Link acceptance criteria back to requirements to ensure traceability.

Define the “Definition of Done” for each requirement. This may include design reviews, code complete, passing unit tests, updated documentation and stakeholder sign‑off.

6) Prioritize ruthlessly

Prioritization prevents “everything is a must.” The MoSCoW method—Must, Should, Could, Will not—categorizes requirements based on their importance and ROI. Atlassian explains that “must haves” are essential for success, “should haves” are important but not critical, “could haves” are nice to have, and “will not haves” are explicitly deferred. Other frameworks include RICE (Reach, Impact, Confidence, Effort), Value vs. Effort matrices and Kano models. The right method depends on your context. Whatever you choose, document your prioritization rationale and revisit it as assumptions change.

7) Use prototypes, wireframes and design guidelines

Visual prototypes validate flows and help stakeholders imagine the product. Start with low‑fidelity wireframes to test layout and navigation, then refine with high‑fidelity designs. Connect each screen to its related requirement; avoid designing beyond what’s specified. Capture design constraints such as brand colours, typeface, platform conventions and accessibility guidelines. At Parallel, we often co‑create prototypes with engineers to surface technical constraints early.

8) Document technical constraints, dependencies and risks

List known limitations (e.g., “The mobile app must support offline mode only for caching data under 10 MB”), dependencies (e.g., third‑party API availability) and inter‑feature relationships. Maintain a risk log with mitigation strategies. For instance, a dependency on a beta API might have a mitigation plan to use a fallback or delay the feature.

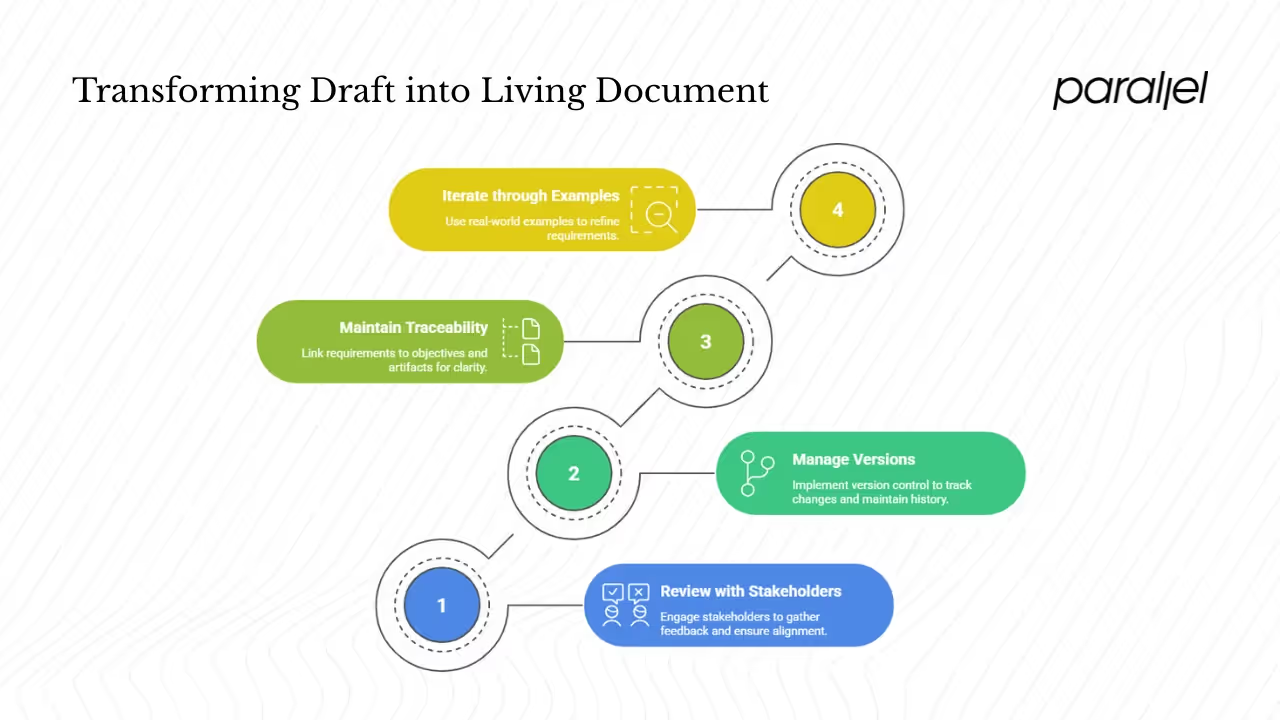

Step #4: Turn your draft into a living document

1) Review with stakeholders

Schedule walkthroughs with design, engineering, marketing and leadership. Encourage questions and dissenting opinions early. Our experience shows that investing a few hours in PRD reviews saves weeks of rework. Aim for consensus, not unanimous agreement. Document feedback and iterate—requirements are hypotheses until validated.

2) Manage versions and changes

Requirements evolve as you learn more. Use version control or a collaboration tool that tracks changes and maintains history. Communicate updates to all teams; avoid silent revisions that create confusion. When adding new requirements or changing priorities, assess the impact on existing work and adjust timelines accordingly. Version control isn’t just a developer’s tool; it’s a product management discipline.

3) Maintain traceability and link artefacts

Traceability ties high‑level objectives to specific requirements, design assets, code and tests. Gartner notes that many teams still use general document tools, leading to poorly managed requirements without traceability. The result: costly user acceptance testing and remediation late in the process. Using a single system (like Jira, Confluence or dedicated requirements management tools) connects discussions and decisions. Link each requirement to its user story, design mockup, test case and acceptance criterion. This end‑to‑end chain accelerates debugging, change impact analysis and compliance audits.

4) Iterate through examples

One way to learn how to write product requirements is by dissecting real examples. Consider a new feature like “two‑factor authentication (2FA).” Start with the problem: users need extra security for account access. Draft use cases (enable 2FA, log in with 2FA, disable 2FA), write user stories (“As a security‑conscious user, I want to enable 2FA so that my account is protected”), list functional requirements (generate and verify one‑time codes via SMS/app, allow recovery codes), define non‑functional constraints (response within 200 ms, 99.99 % availability, comply with GDPR), set acceptance criteria using Given–When–Then, prioritize as a “Should Have,” map dependencies (SMS service provider) and articulate risks (SMS delivery failures). Walk the draft through your stakeholders and revise based on feedback.

Pitfalls to avoid and best practices

A key part of how to write product requirements is avoiding common pitfalls and embracing disciplined practices.

Common pitfalls

- Over‑specifying: Providing implementation details or dictating UI decisions can stifle creativity. Focus on outcomes, not solutions.

- Under‑specifying: Vague language like “user friendly” leads to conflicting interpretations. Use concrete, testable statements.

- Ignoring non‑functional aspects: Performance, security and reliability cannot be afterthoughts.

- Scope creep: Uncontrolled addition of requirements dilutes focus. Use prioritization frameworks and revisit scope regularly.

- Static documents: Requirements evolve; treat the PRD as living. Outdated documents create confusion and rework.

- Unresolved stakeholder conflicts: Address disagreements early; unresolved tensions resurface as last‑minute surprises.

- Lack of traceability: Without links between requirements, tests and code, changes become expensive.

Best practices

- Clarity and consistency: Write concise sentences; avoid jargon unless defined.

- Use templates and modular structure: Reuse proven sections and adjust for your context.

- Involve cross‑functional teams early: Collective intelligence uncovers blind spots.

- Prioritize ruthlessly: Keep the focus on outcomes that drive business value.

- Treat the document as living: Iterate based on feedback and new insights.

- Visualize flows: Use diagrams and wireframes to complement text; they reduce misinterpretation and accelerate consensus.

Conclusion

Learning how to write product requirements is a craft. It’s not about filling out a template; it’s about creating clarity so teams can build the right product. Our experience at Parallel shows that investing in solid requirements pays dividends later—in reduced rework, faster delivery and happier users.

Start with a small feature. Write down the problem, user story, acceptance criteria and non‑functional expectations. Review it with your team. Iterate. Over time, you’ll develop your own playbook for how to write product requirements that fits your context.

Use this guide as a blueprint, not a straitjacket. Your product’s success depends on understanding your users, aligning your team and capturing the what and why in a way that inspires excellent execution.

FAQ

1) How to write a product requirement?

Begin with user needs and business context. Define a clear goal, write user stories (e.g., As a user… I want… so that…), derive functional and non‑functional requirements, set acceptance criteria using a format like Given–When–Then, prioritize, and iterate through stakeholder feedback.

2) What are product requirements?

They are documented descriptions of what a product must do (functional) and how it should perform (non‑functional)—covering user needs, constraints and success metrics.

3) How to write a requirement example?

A functional requirement example: As a user, I want to reset my password via an email link so that I can regain access. A non‑functional example: The system shall respond within 200 ms under a load of 1,000 concurrent users.

4) How to write requirements as a product owner?

Focus on outcomes over solutions, keep the user at the centre, involve engineers and designers early to check feasibility, refine continuously and maintain traceability. Prioritize relentlessly, and remember that good requirements reduce rework and accelerate delivery.

.avif)