How to Write a Research Plan: Guide (2026)

Discover how to write an effective research plan that outlines goals, methods, timelines, and resources.

When I talk to teams building new products, the same pattern surfaces: they jump straight into building without a clear research plan. They interview a few friends, run a survey or two, and then move on. Weeks later, they realise the insights weren’t actionable, the priorities were mis‑set and decisions have to be reversed. This article is a guide on how to write a research plan that avoids those missteps. I’ll walk you through the key parts of a lean yet thorough plan, drawing on my own practice at Parallel, insights from respected design groups and up‑to‑date data from 2024–2025.

I’ll explain what a research plan is in this context, why it matters for product teams, and how it connects academic rigour with fast‑moving product work. You’ll find tips for framing the problem, setting objectives, choosing methods, plotting logistics and communicating with stakeholders. The goal is simple: help founders, product managers and design leaders create research plans that keep projects focused, reduce risk and produce findings that can actually drive product decisions.

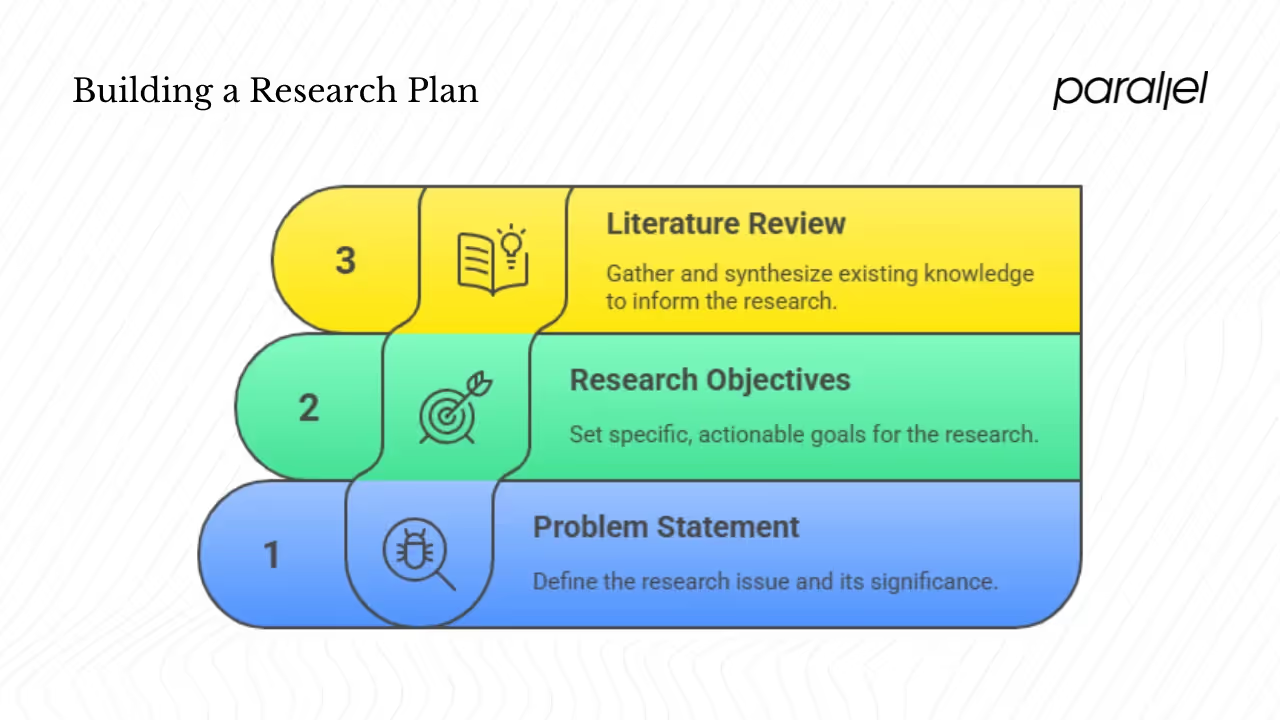

Step #1: Framing and foundations

1) Problem statement and research significance

A research plan begins with a clear description of the issue you’re trying to understand. The problem statement articulates the gap, pain or unknown that prompted the research. A good statement keeps the scope realistic and brings attention to what matters. Without it, research drifts and stakeholders later argue about whether it answered the right questions. Nielsen Norman Group describes a research plan as a document that outlines the goals, methods and logistical details of a study and emphasises that creating one keeps everyone informed about the purpose and scope.

Why take time to write a tight problem statement? It shapes focus and sets boundaries. It signals what is in scope and what isn’t, which helps avoid endless exploration. To express significance, connect the problem to business metrics, user pain or strategic outcomes. For example, if conversion through onboarding is low, state how understanding why users drop off will influence roadmap prioritisation. Keep it brief and concrete.

Understanding how to write a research plan starts with this step. If you skip over the problem statement or treat it as an afterthought, your entire plan will be built on shaky ground. Taking a few minutes to articulate the problem and why it matters will pay off later when stakeholders ask why the research was necessary.

Examples:

- Generic: “We don’t know if users understand our pricing model.”

- Product context: “Free‑tier sign‑ups convert to paid at 2%. We need to identify why users hesitate at the pricing page and whether the language or features are confusing.”

2) Research objectives and research questions

Once you have a problem statement, define objectives—what you hope to achieve. Objectives should be specific and actionable so you can later evaluate if they were met. Research questions flow from objectives and guide the choice of methods. The ProjectManager template notes that a research plan should outline objectives and methods, while a separate section lists research questions or hypotheses. Think of objectives as the high‑level goals (“understand why pricing is unclear”) and questions as the things you’ll ask or measure to achieve those goals (“Which messages cause confusion?”, “What alternative pricing models do users compare us to?”).

Tips for strong objectives:

- Keep them actionable. If you say “explore user behaviour,” clarify what decisions you want to inform.

- Make them measurable. Decide how you will know the objective is achieved—through themes identified, usability metrics, or behavioural data.

- Link each to a business decision. Without that link, even well‑run research may be ignored.

From each objective, derive research questions. Each method you choose should map back to at least one question. If your project is evaluative (e.g., A/B testing a new feature), you might go further and state hypotheses—testable predictions with a null and alternative form. Hypothesis‑driven research is common in experiments and helps clarify what success looks like. For generative research (like exploratory interviews), leave questions more open‑ended.

3) Literature review and literature sources

Even in a lean product context, you should review existing knowledge. A literature review grounds your plan in what’s already known, helps avoid reinventing the wheel and can surface best practices. It doesn’t have to be an academic deep dive; look at:

- Academic papers for theory or prior findings relevant to your domain.

- Industry reports from groups like ESOMAR or Forrester.

- Competitor analyses and internal analytics.

- Previous user research your team or peers have conducted.

In lean settings, allocate a few days to gather, skim and synthesise the key takeaways. Use what you find to refine research questions, choose methods and avoid duplicating work. For example, if a 2025 UX report shows that boosting UX budgets by 10% can lift conversions by 83%, that statistic strengthens the argument for investing in usability testing over yet another feature.

Step #2: Designing the methodology

1) Methodology design (research design)

Many teams confuse methodology and methods. Methodology is the overall theory of how research should proceed, whereas methods are the specific techniques used to gather data. Research.com notes that methodology provides “the underlying theory and analysis of how a study should proceed” while methods are “practical procedures used to generate and analyze data”. In practice, this means deciding whether a qualitative, quantitative or mixed approach is appropriate, and why.

When choosing methods, consider the stage of your product and what you need to learn. Generative, qualitative methods (interviews, diary studies) uncover motivations and pain points, ideal early in discovery. Evaluative, quantitative methods (surveys, A/B tests) measure behaviour or attitudes and are useful for validating solutions at scale. A mixed approach triangulates insights; research.com notes that mixed methods fuse quantitative and qualitative approaches to present multiple findings.

Trade‑offs:

- Cost and time: Interviews yield depth but require more coordination. Surveys scale quickly but may miss nuance.

- Depth vs. breadth: Qualitative work surfaces unexpected insights; quantitative work provides confidence in trends.

- Generalisation: Large samples support statistical generalisation; small samples provide detail but may not generalise.

Map each research question to at least one method. If a question requires understanding motivations, choose a qualitative method. If a question needs measuring the magnitude of a behaviour, pick a quantitative method.

Learning how to write a research plan also means deciding which methods make sense for your context. The methodology section is where you match each research question to a technique, explain the rationale and address trade‑offs. A well‑reasoned methodology reassures stakeholders that you’ve thought through the options and chosen the most efficient path.

2) Data collection methods

Common methods and when to use them:

- Interviews: Semi‑structured conversations that delve into behaviours and motivations. Good for early discovery. They can be moderated (in person or remote) or unmoderated (participants record themselves). Keep sessions under an hour; always record (with consent) and take notes.

- Surveys: Useful for quantifying behaviours and attitudes. Keep them short, test the survey with a few users and avoid leading questions. Surveys can follow interviews to validate patterns across a broader sample.

- Usability tests: Sessions where users perform tasks on a prototype or live product while thinking aloud. This method uncovers friction points. Include a set of tasks and success criteria; decide whether sessions will be moderated or unmoderated.

- Field observations: Shadow users in their natural environment to understand context. This is valuable when building tools for specific industries (e.g., logistics, healthcare) but requires more time and field access.

- Diary studies: Participants record their activities and feelings over days or weeks. Useful for longitudinal insights, but requires incentives and careful prompts.

- Analytics and logs: Product analytics reveal what people actually do. They complement qualitative methods and can guide where to dive deeper.

When recruiting, define inclusion and exclusion criteria clearly. NN/g advises describing participant characteristics, sample size and inclusion/exclusion criteria in your plan. For example, if you’re researching a B2B tool, include participants who use similar tools and exclude those unfamiliar with the domain. For small budgets, start with 5–8 participants for interviews or tests; you often see patterns by then.

Consider logistics: will sessions be remote or in person? What tools (video conferencing, screen sharing, analytics platforms) are needed? Plan incentives and scheduling. If using remote testing, choose platforms with builtin recording and consent features. Document all of these details so the team can replicate the study later.

3) Analysis plan

Analysis should not be an afterthought. Decide ahead how you will process and interpret data.

For qualitative data, common techniques include coding transcripts, thematic analysis and affinity mapping. Coding involves tagging quotes or observations by theme; affinity mapping groups related observations to surface patterns. Tools like Notion, Dovetail or Miro help organise and visualise themes. Triangulate across data sources (interviews, usability tests, support tickets) to increase confidence.

For quantitative data, decide on descriptive statistics (mean, median, frequency), hypothesis tests (t‑tests, chi‑square), or regression analyses. Research.com stresses that qualitative and quantitative approaches have distinct purposes—quantitative data seeks to generalise findings, while qualitative provides contextual understanding. If you’re running A/B tests, plan your sample size, metrics and statistical thresholds ahead of time.

For mixed methods, integrate both analyses. For example, use analytics to identify drop‑off points in a funnel, then conduct interviews focused on those steps to understand why. Triangulate findings to validate patterns and spot contradictions. Always tie analysis back to research questions and objectives to keep it relevant.

Data validation is key. Use inter‑rater reliability for coding, run pilot surveys to test questions and cross‑check analytics with other data sources. When dealing with noise, look for patterns across participants rather than outliers and be transparent about limitations.

4) Hypothesis formulation (if applicable)

Not every study needs hypotheses, but they’re powerful when testing specific solutions. Hypotheses should be directional and testable. A simple structure is: “If [change], then [expected outcome], because [rationale].” For example: “If we simplify the pricing page copy, then sign‑up completion will increase, because users currently struggle to understand our value proposition.” State a null hypothesis (no difference) and an alternative (expected difference). Link hypotheses to objectives and ensure your data collection and analysis plan can test them.

Step #3: Logistics and execution strategy

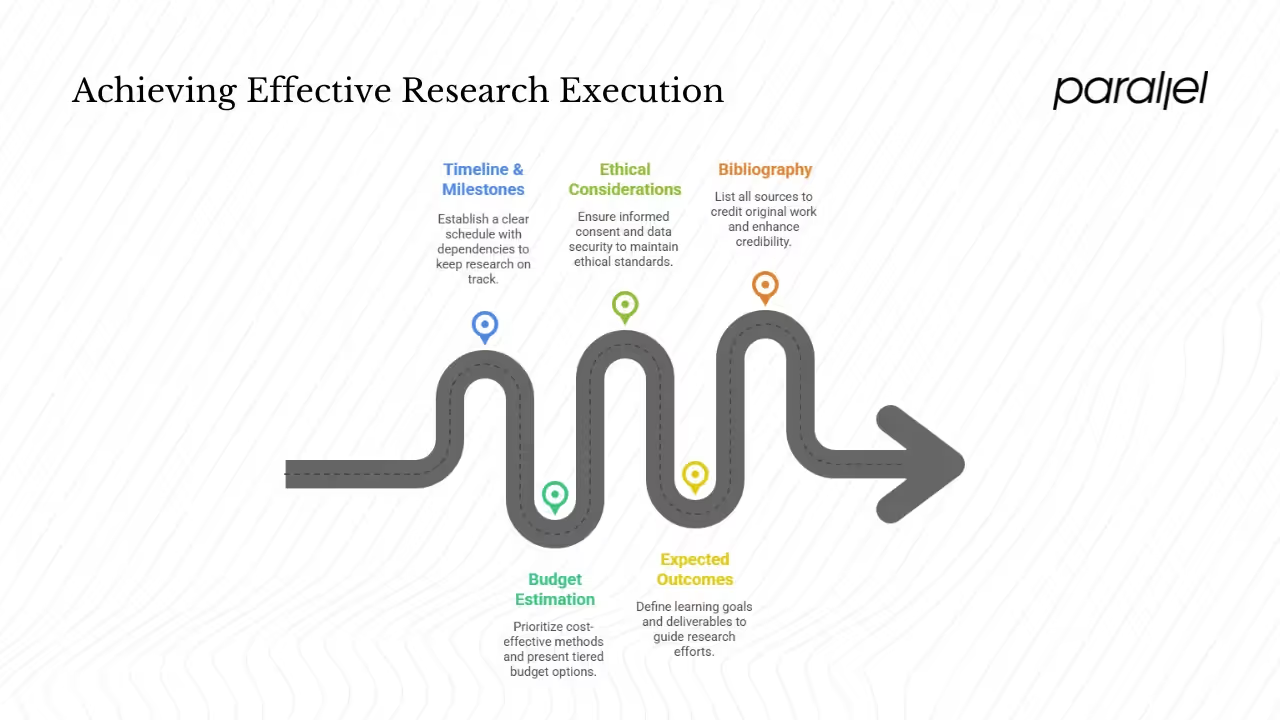

1) Timeline and milestones

Timeboxing research work is essential. Without a schedule, research can drift or get de‑prioritised. A research plan should include major phases: preparation (stakeholder interviews, literature review), recruitment, data collection, analysis, reporting and iteration. ProjectManager’s template emphasises that a research plan provides a clear timeline, ensuring tasks stay on track. Create a simple Gantt chart or calendar with dependencies: for example, recruitment begins once the screener is final, analysis begins after half the sessions are complete, etc. Include buffer time for no‑shows or technical issues.

When figuring out how to write a research plan, treat the timeline as more than just dates. It’s a communication tool that helps others see how long each stage will take and where they might need to contribute. A realistic schedule builds trust and reduces the pressure to rush through critical steps.

2) Budget estimation

Costs can include participant incentives, software subscriptions (survey tools, transcription services), team hours, recruitment services, travel and equipment. If budgets are tight, prioritise methods with high insight‑to‑cost ratios. Remote sessions often reduce travel costs and allow for broader geographic reach. According to UXCam’s 2025 statistics, every dollar invested in UX returns $100, and increasing UX budgets by 10% can boost conversions by 83%—powerful numbers when justifying research spend. Present tiered estimates: a lean option (minimal incentives, remote-only), a moderate option (combination of remote and in‑person), and a robust option (larger sample, professional recruitment). Explain trade‑offs so decision‑makers know what they’re sacrificing when they cut costs.

3) Ethical considerations

Ethics are non‑negotiable. Obtain informed consent; participants must know why the study is being conducted and how their data will be used. Maintain anonymity and confidentiality by removing identifying information from transcripts. NN/g lists consent forms and screeners as relevant documents to include in research plans. Secure your data—store recordings on encrypted drives and restrict access. If your research touches on sensitive topics or involves vulnerable populations, consult an ethics review board or legal team. Be transparent about potential conflicts of interest and ensure participants can withdraw at any time. Plan how long you’ll retain data and when it will be destroyed.

4) Expected outcomes and deliverables

Think ahead about how results will be shared. Deliverables may include research reports, slide decks, dashboards, personas, journey maps or prototypes. Frame expected outcomes not as guaranteed answers but as learning goals tied to decisions. For example, “Identify the top three points of friction in onboarding and recommend changes” is more useful than “Improve onboarding experience.” Document assumptions and risks so stakeholders are aware of uncertainties. Include suggested follow‑on research if the study uncovers new questions.

5) Bibliography / references

Always list the sources you consulted—academic papers, industry reports, previous research, competitor analyses. This both credits the original work and strengthens your own credibility. Use a citation style that your team can follow easily (APA, MLA or a simple footnote format). ProjectManager’s template includes a references section; adapt it to your needs.

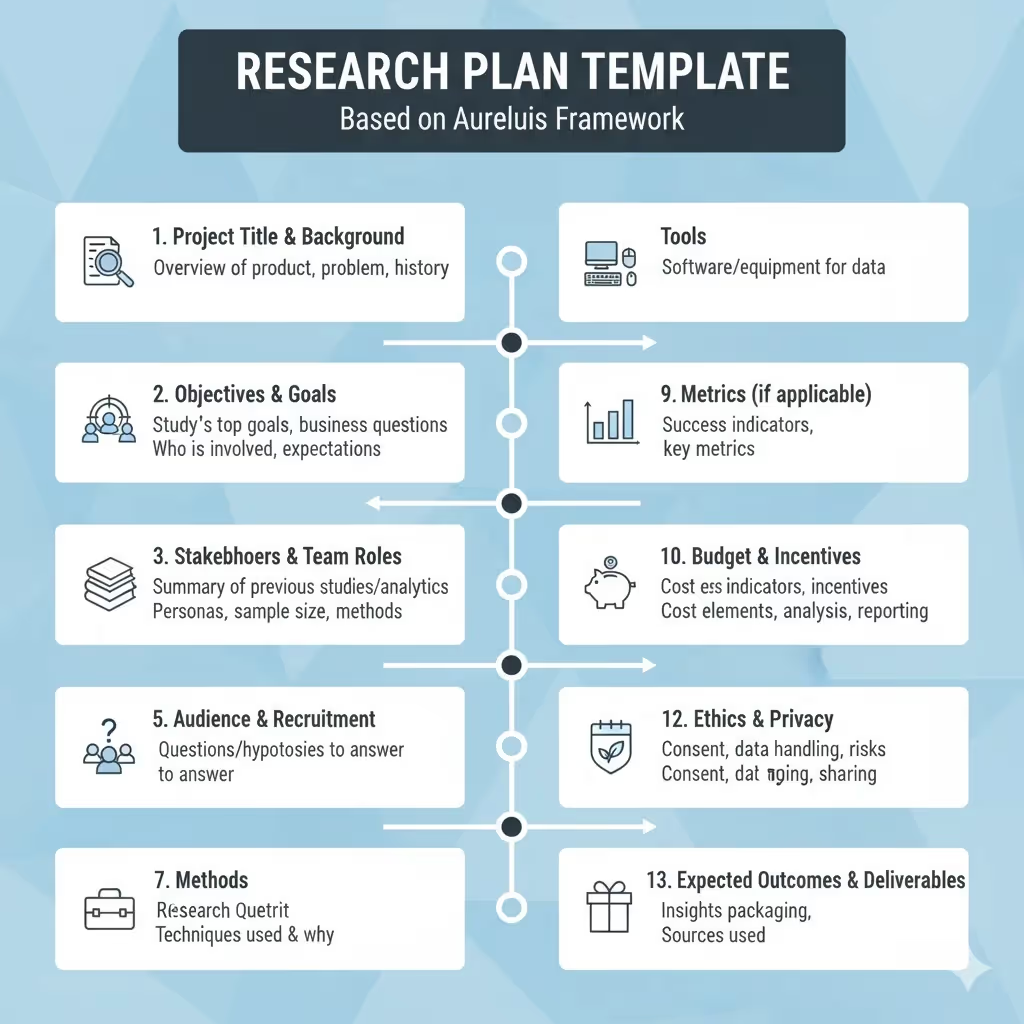

Putting it all together — template and walkthrough

Research plan template outline

Based on our practice and the Aurelius template, here’s a lightweight outline you can follow:

- Project title and background – brief overview of the product, problem and history.

- Objectives and goals – list the top goals of the study and how they relate to business questions.

- Stakeholders and team roles – who is involved and what they expect.

- Existing research – summary of previous studies or analytics.

- Audience & recruitment plan – describe personas or segments, sample size and recruiting methods.

- Research questions – the questions or hypotheses you aim to answer.

- Methods – detail the techniques you’ll use and why they answer your questions.

- Tools – list software or equipment needed for data collection and analysis.

- Metrics (if applicable) – define success indicators or key metrics.

- Budget and incentives – outline cost elements and incentives.

- Timeline and milestones – schedule for preparation, fieldwork, analysis and reporting.

- Ethics and privacy – consent process, data handling, risks.

- Expected outcomes and deliverables – how insights will be packaged and shared.

- References – sources used.

This outline shows how to write a research plan step by step. You can treat it as a checklist or adapt it to suit the scale of your project. By following a consistent structure, you ensure that nothing important is missed and that stakeholders know where to find critical information.

Annotated example

To make this concrete, let’s look at a simplified example inspired by the ‘InstaCar’ research plan from the Webflow case. Suppose you’re building a peer‑to‑peer car‑sharing feature and want to validate assumptions around adoption and trust.

Background: Peer‑to‑peer car sharing has low adoption due to trust and convenience concerns. You hypothesise that clear protections and frictionless key transfer will increase willingness to participate.

Objectives:

- Understand car owners’ motivations for renting out their vehicles.

- Identify the top barriers (e.g., damage, scheduling issues).

- Test the prototype of the booking flow to uncover usability issues.

Research questions:

- What is the most significant barrier to listing a personal car for sharing?

- How do renters currently navigate the process, and where do they experience friction?

- Does adding a step explaining insurance coverage improve trust?

Methods:

- Literature and competitor analysis to understand the market.

- Semi‑structured interviews with 6–8 car owners who have rented or considered renting their cars.

- Remote usability tests of the booking prototype with 5 renters.

Participants: Car owners aged 25–45 in urban areas.

Timeline: One‑week recruitment, two days of interviews, one day of usability testing, three days of analysis and reporting. Include a buffer for schedule changes.

Deliverables: A report summarising themes with quotes, a prioritised list of usability issues, and design recommendations.

Checklists and adaptation tips

Use the outline above as a checklist. Before sharing your plan, ask:

- Does the problem statement tie back to a business decision?

- Are objectives specific and measurable?

- Do methods clearly answer research questions?

- Have you listed resources, timelines and costs?

- Is there a clear plan for analysis and data handling?

For small projects or early‑stage startups, simplify. You may combine sections (e.g., objectives and questions), recruit fewer participants and use free tools. For larger projects or regulated industries, include more detail on sampling, consent and legal compliance. Adapt the level of detail to the scale and risk of the project.

As you refine how to write a research plan for your own context, remember that flexibility matters. Your first draft won’t be perfect, and that’s fine. The act of writing it down forces you to think through the logistics and trade‑offs, which is the real value.

Communication matters. Share your plan with stakeholders early, invite feedback and iterate. NN/g recommends sharing the plan to get buy‑in and set expectations. When presenting the plan, focus on the decisions it informs, the timeline and what is expected of stakeholders.

Aligning with stakeholders and execution tips

1) Getting stakeholder buy‑in

Engage stakeholders early. Invite them to a problem‑framing workshop where you co‑create the research objectives. Ask them what decisions they hope to make from the insights. Sharing drafts of the research plan before fieldwork fosters trust and reduces last‑minute changes. Provide a short summary of the plan emphasising why the research matters and what questions will be answered.

Clarify roles: who will observe sessions, who will review findings, and who will decide on next steps. Provide guidelines for observers so they don’t disrupt sessions. Encourage note‑taking and debriefs after sessions to keep everyone aligned on what’s being learned.

2) Communicating trade‑offs and maintaining accountability

Stakeholders will often ask to shorten timelines or reduce sample sizes. Be transparent about the implications. For example, explain that fewer participants may miss edge cases. Use the UX statistics discussed earlier: small investments in research can yield outsized returns—every second saved in page load increases conversions by 2%, and 74% of visitors return to sites with good mobile UX. Framing research as a risk‑reduction tool helps justify its cost.

Maintain accountability by setting milestones and sharing progress. At each stage—recruitment, data collection, analysis—brief stakeholders on status and preliminary insights. This transparency builds confidence and reduces surprises at the end.

3) Adapting and pivoting

Projects rarely go exactly as planned. Participants may cancel, prototypes may change and new questions may arise. Treat your research plan as a living document. Record changes and their rationale. If you need to pivot—perhaps because early interviews reveal a different problem—update objectives and share the revised plan. The act of documenting changes maintains transparency and makes future retrospectives easier.

4) Version control and documentation

Use version control (a shared document or repository) for your plan. Track who edited what and when. Store related documents—screeners, interview guides, consent forms—in a shared folder. NN/g notes that research plans often serve as a place to store relevant documents. Keeping everything together helps others replicate or audit the study later.

Conclusion

Writing a research plan may seem like extra paperwork when deadlines loom, but it pays dividends. A well‑crafted plan clarifies what you’re trying to learn, provides a map for gathering and analysing data, and sets expectations with stakeholders. It reduces risk by ensuring you ask the right questions of the right people and that your findings can inform product decisions. At Parallel, we’ve seen that projects with a clear research plan move faster and change direction less often because the team is grounded in evidence.

The steps covered—defining the problem, setting objectives and questions, reviewing literature, designing methodology, planning logistics, considering ethics and outlining deliverables—may feel like a lot. Start small if you need to. Use the template and example provided, adjust for your context and refine over time. The way to write a research plan framework presented here is meant to empower you to conduct thoughtful research without bogging down your team. Invest a few hours upfront, and you’ll save weeks later.

Now it’s your turn. Use the outline to draft your next research plan. Share it with your team. Ask for feedback. Iterate. You’ll find that clarity at the beginning leads to confidence in the end.

Practising how to write a research plan will become easier each time you do it, and you’ll soon build a library of documents that guide your product decisions.

FAQ

1) What are the five steps of a research plan?

- Define the problem and objectives. Write a clear problem statement and specify what decisions the research will inform.

- Review existing knowledge. Conduct a short literature review—look at academic papers, industry reports and previous research to avoid duplication and refine your questions.

- Design the methodology. Decide on qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods, plan data collection and analysis, and define participant criteria.

- Plan logistics. Draft a timeline, budget, recruitment plan and ethical considerations, and list the tools and documents you’ll need.

- Collect and analyse data, then communicate. Execute the research, analyse it according to the plan, and prepare deliverables that answer the original questions.

2) How does a research plan look?

A research plan is a structured document that outlines the key elements and steps involved in conducting a research project. It includes a problem statement, objectives, research questions or hypotheses, methods, recruitment and sampling details, timelines, budgets, ethical considerations and expected outcomes. It’s typically a few pages long with headings and bullet points, serving as both a roadmap and a communication tool.

3) What are the key elements of a research plan?

Key elements include:

- Title and background – why the research matters.

- Objectives and questions – what you hope to learn and the questions you’ll ask.

- Stakeholders and team – who is involved and their roles

- Existing research – what prior work informs this study.

- Audience & recruitment – who you will talk to and how you will recruit them.

- Methods and tools – how you will collect and analyse data.

- Timeline and budget – scheduling and financial plan.

- Ethical considerations – consent, privacy and data handling.

- Expected outcomes and deliverables – how results will be shared.

- References – list of sources consulted.

4) How long should a research plan be?

Length depends on context. In early‑stage startups or small product teams, a clear 2–5‑page document is often enough. It should be long enough to cover the elements above but concise enough for busy colleagues to read. For academic projects or funded proposals, plans may run 10 or more pages with detailed literature reviews and formal methodologies. Focus on clarity and usefulness rather than length; include what your team needs to make decisions and execute the research effectively.

.avif)