How to Write User Stories: Guide (2026)

Discover how to write effective user stories that capture user needs and guide agile development.

A user story is not a task list or a technical spec. It’s a concise narrative that captures who a feature is for, what they want to achieve and why that goal matters. Atlassian’s agile coach defines a user story as an informal explanation of a software feature told from the end‑user’s perspective. It exists to articulate value rather than enumerate tasks.

In my work with early‑stage SaaS and AI teams at Parallel, I’ve seen how well‑crafted user stories focus teams on outcomes instead of output. They improve clarity, align disparate contributors and create momentum when resources are scarce. This guide explains how to write user stories that honour user needs while driving product strategy.

Quick Start: How to Write a User Story

User stories help teams focus on user needs, not just technical tasks. Here’s a step-by-step overview:

- Identify the user (persona): Who is this for? Be specific.

- Clarify their goal: What do they want to achieve?

- Define the value: Why does this goal matter to them?

- Use the classic format:

“As a [persona], I want [goal], so that [benefit].” - Add acceptance criteria: What conditions must be true for the story to be done?

- Review & refine: Discuss with your team, split if it’s too large.

- Prioritize & estimate: Add to backlog based on impact and effort.

What’s the role of user stories in agile and startups?

In agile, a user story is the smallest unit of work that delivers a user‑centric outcome. Atlassian notes that user stories put end users at the centre of the conversation and use simple language to provide context for development teams. They’re not requirements but catalysts for conversations about solving problems. A single story describes an end goal from the user’s perspective and becomes a building block for epics and initiatives.

Early‑stage startups juggle vision, fundraising and resource constraints. User stories help by anchoring discussions on user value. Unlike a task list that encourages teams to tick boxes, a backlog of user stories encourages curiosity about who the user is and why they care. GeeksforGeeks explains that user stories provide an informal description of requirements from the end‑user’s perspective and can be written by stakeholders, end users or team members. When integrated into a product backlog, stories allow product managers and founders to prioritise features based on user impact rather than technical curiosity. During sprint planning, teams estimate stories and slice larger efforts into epics and tasks. As the 17th State of Agile Report notes, Scrum remains the most popular team‑level methodology (used by 63% of respondents) and 71% of survey takers use agile in their software‑development life cycle. In other words, small, incremental stories remain central to how teams organise their work.

User stories also act as a communication tool between the product owner, developers, designers and stakeholders. They make assumptions explicit, give context for design decisions, and allow conversations to focus on value and feasibility. This cross‑functional alignment is essential for startups where decision cycles must be short. Stories ensure that team members ask why before committing to what.

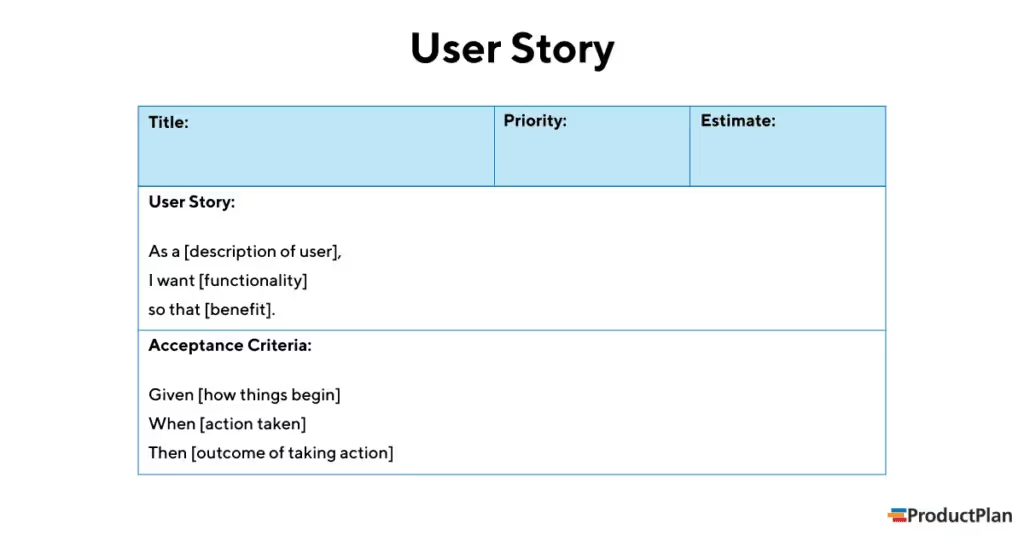

Core components of a user story

A good user story has three core components: persona, need/goal and value. Konrad’s design guide reminds us that complete stories combine three pieces of information—who the user is, what they want and why they want it. Atlassian breaks down the classic format as:

- As a [persona]: Who are we building this for? This isn’t just a job title; it’s a specific user you’ve met or researched.

- I want [goal]: Describe the user’s intent, not the implementation. It should remain free from UI details.

- So that [benefit]: Explain the larger benefit or problem solved.

Following this simple structure keeps the story outcome‑oriented. For example, “As a new customer, I want to upload my data so that I can see personalized insights in under two minutes.” Notice how it captures motivation rather than describing a button or API call.

Beyond the core triad, mature teams often add supplementary elements. GeeksforGeeks lists important terms that accompany stories: title, persona, desire, benefit and acceptance criteria. Acceptance criteria define the conditions of satisfaction—objective statements that must be true for the story to be considered done. Including them up front reduces ambiguity and fosters testability. Epics group related stories together, and tasks further break down stories into actionable technical work. A story should be small enough to be completed in one sprint; otherwise it should be split into multiple stories or turned into an epic.

User stories differ from use cases or requirements documents by prioritising conversation over exhaustive documentation. Konrad emphasises that stories aren’t requirements; they invite discussions about solving problems. The story itself is only a placeholder for a richer dialogue about user needs.

Writing good user stories: best practices

1. Start with empathy and clarity

We write stories to build empathy. You need to understand the persona’s context, pain points and motivations. This requires user research: interviews, surveys or analytics. Once you know who the user is, capture their goal in their own words. Atlassian advises using non‑technical language so that any team member can understand the story’s intention. Avoid vague adjectives (“intuitive”, “seamless”) and focus on observable outcomes.

2. Keep them short and conversational

Stories should be one or two sentences long. They’re conversation starters rather than exhaustive specifications. Robin’s rule of thumb: if the story takes up more than a sticky note, it’s probably too detailed. GeeksforGeeks notes that each note typically contains 20–25 words. The brevity encourages the team to discuss details together, rather than hiding them in documentation.

3. Specify acceptance criteria

Without clear acceptance criteria, stories risk becoming ambiguous. Use bullet lists of testable statements describing what must be true for the story to be complete. For example: “Data appears within 10 seconds on dashboard,” “File types larger than 2 GB are rejected with an error message.” Acceptance criteria help developers, designers and testers align on done‑ness and support test automation.

4. Focus on value, not implementation

User stories describe what and why, not how. Resist the urge to specify UI elements or system architecture within the story. Atlassian warns that describing any part of the UI means you’re missing the point. Implementation details can be captured in tasks or technical notes linked to the story. The goal is to allow the team to devise creative solutions.

5. Use conversations to refine and split

The story card triggers a conversation. In sprint planning and backlog refinement sessions, discuss the story with developers, designers and stakeholders. Ask clarifying questions such as: Are there hidden user personas? Does this story depend on another? If the story seems too big to complete in one sprint, use splitting techniques: slice by path (different user flows), data (small data sets first), rules (simplify assumptions), interfaces (leave integrations for later) or create spikes (research tasks). Keeping stories small reduces risk and increases predictability.

6. Integrate UX and research work

User stories shouldn’t just reflect development tasks. Nielsen Norman Group recommends using story maps to make UX activities visible. Add subtasks for research, design and testing so that these efforts are acknowledged during sprint planning and tracked in the backlog. Each story should include acceptance criteria for both functional and user experience quality.

7. Don’t forget the three C’s

Bill Wake introduced the 3 C’s: Card, Conversation and Confirmation. GeeksforGeeks summarises them succinctly:

- Card: The written story itself (often on a physical or digital card).

- Conversation: The dialogue among team members that elaborates the story.

- Confirmation: The acceptance criteria confirming that the story is complete.

Embracing the 3 C’s keeps stories lightweight but grounded in shared understanding.

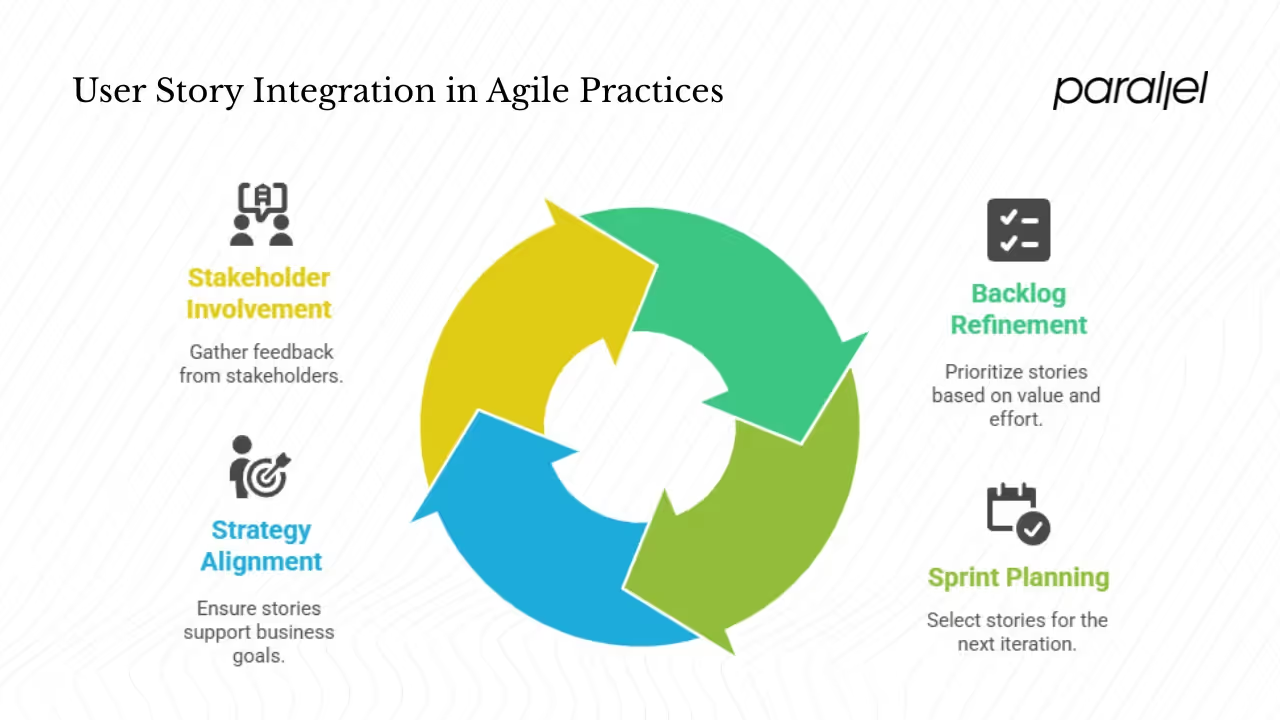

Connecting user stories to agile and startup practices

Product backlog refinement

For startups, the product backlog often doubles as a roadmap. User stories provide the granularity needed to order work by user value. During backlog refinement, product owners rank stories based on strategic goals, user impact and effort. Atlassian notes that in Scrum and Kanban, stories fit neatly into sprints or workflow queues and help teams improve estimation and planning. At Parallel, we use story points and planning poker to size stories and identify ones that need splitting. This practice aligns with the 17th State of Agile Report’s observation that teams use t‑shirt sizes, Fibonacci sequences or planning poker for estimation.

Sprint planning and estimation

During sprint planning, the team selects a batch of stories that can be completed in the next iteration. Stories should be small enough to finish within the sprint; longer ones become epics. Estimating stories using story points helps measure relative complexity and capacity. The State of Agile report found that engineering and R&D are the fastest growing adopters of agile, rising 16% over 2022. That growth underscores the need for lean planning practices; user stories enable R&D teams to adapt quickly to changing priorities without long requirement documents.

Aligning with broader strategy

User stories aren’t the full strategy, but they must map to it. Each story should link back to a value proposition or business goal. The State of Agile report notes that the top benefits of agile are improved collaboration and better alignment to the business. To achieve this, product leaders should connect each story to objectives and key results (OKRs) or themes in the roadmap. At Parallel we ask, “How does this story support our quarter’s focus on retention?” This ensures we don’t waste cycles on features that don’t drive outcomes.

Stakeholder and customer involvement

User stories are a way to involve stakeholders early and often. Presenting a story to a customer or stakeholder invites feedback: Does this reflect your real pain? Does the benefit resonate? It’s common for founders to build features based on assumptions; user stories create a check against this tendency by emphasising the user’s voice. Sharing stories with investors can also clarify how development relates to the company’s value proposition.

Practical steps: how to write a user story

The how to write user stories process can feel intimidating. Here’s a step‑by‑step approach I’ve used with hundreds of early‑stage teams:

- Identify the persona. Review your user research and select a specific persona. If you’re unsure, schedule quick interviews or look at analytics to understand user behaviours. Use the persona to build empathy and avoid generic roles.

- Clarify the user’s intent. Ask what the user is trying to achieve. Focus on their goal, not the software features. Konrad emphasises that user stories should be inspired by real observations.

- Connect to value. Ask “Why does this matter?” or “What benefit does the user get?” The benefit could be saving time, feeling confident or achieving a business outcome. Without a clear “why,” the story will be weak.

- Write the story in the classic format. Use “As a [persona], I want [goal] so that [benefit].” Atlassian provides examples such as “As Max, I want to invite my friends, so we can enjoy this service together”. Keep it brief.

- Add acceptance criteria. Write clear, testable conditions. For instance: When the user uploads a CSV file over 5 MB, it shows an error message within 3 seconds. Include criteria covering functional outcomes and experience quality.

- Review with stakeholders. Bring the story to developers, designers and stakeholders. Ask if the persona, goal and value are clear. Iterate based on feedback. GeeksforGeeks emphasises that the story invites conversation.

- Split if necessary. If the story is too large or complex, split it by personas, data sets, business rules or user paths. Use spikes to investigate unknowns. Ensure each story can fit into a sprint.

- Estimate effort and add to the backlog. Estimate the story’s complexity (story points) and prioritise it in the backlog. Align the priority with strategic objectives and user impact.

Following this sequence will help your team craft clear, valuable stories. The steps mirror the “Card – Conversation – Confirmation” model and encourage continuous communication.

Advanced tactics and tips

1) Use role modelling and collaborative workshops

When creating a new backlog, gather cross‑functional teams in a workshop to brainstorm user stories. Set a timer and generate as many stories as possible for one persona. Konrad suggests writing as many stories as possible within 10–15 minutes. After brainstorming, cluster stories into themes and epics. This collaborative exercise surfaces diverse perspectives and uncovers hidden requirements.

2) Align with stakeholder needs early

Invite stakeholders to user story workshops. For founders, this could mean investors, domain experts or lead customers. Involving them early builds alignment and uncovers unspoken assumptions. It also helps stakeholders appreciate the iterative nature of agile; they see how each story contributes to larger goals.

3) Tie every story to your value proposition

In early‑stage startups, it’s tempting to chase feature requests or competitor parity. Resist that temptation by mapping stories to your core value proposition. When a new story emerges, ask how it moves the needle on customer acquisition, retention or expansion. The 17th State of Agile report found that 43% of respondents prioritise end‑customer satisfaction while 39% prioritise time to delivery. Use these priorities as lenses to decide whether a story belongs in your next sprint.

4) Emphasise prioritization and focus

Not all stories are equal. Always tackle high‑value stories first, even if they’re complex. At Parallel we rank stories by impact and urgency. Sometimes the “hard” stories unlock critical value; delaying them can stall progress. The State of Agile report notes that small, nimble organisations are highly satisfied with agile’s productivity benefits while medium and large companies struggle to scale. Startups can maintain agility by focusing on value‑first stories and avoiding backlog bloat.

5) Use story mapping and visualization (optional)

For complex products or new initiatives, consider creating a user story map. According to Nielsen Norman Group, a user‑story map is a lean UX‑mapping method that outlines the interactions users go through to complete their goals. Story maps enable teams to define what to build, maintain visibility of how the product fits together and prioritize features to align and guide iterative development. They depict three levels of actions—activities, steps and details—and help teams maintain the big picture. At Parallel, we use Miro or physical boards to create story maps that show the flow from onboarding to retention, making it easier to choose which stories to include in the next release. Story mapping is especially useful for aligning remote teams and demonstrating progress to stakeholders.

Conclusion

User stories are more than sticky notes; they’re a lean, user‑centred tool for guiding agile development. Atlassian reminds us that stories put the user at the centre of the conversation and help teams focus on solving real problems. GeeksforGeeks emphasises that stories are informal and allow multiple stakeholders to contribute. The 17th State of Agile report shows that agile adoption remains high—71% of respondents use agile in their SDLC—and highlights improved collaboration and business alignment as top benefits. By writing concise, outcome‑oriented stories, integrating acceptance criteria, inviting conversation and mapping them to broader strategy, startups can harness the full power of agile. Regularly review and refine your stories, keeping the user’s “why” at the centre. The practice may feel simple, but it unlocks deep clarity and momentum when applied thoughtfully.

Start writing your next user story today. Focus on who it’s for, what they truly need and why it matters. Collaborate, revise and deliver meaningful value. That’s how to write user stories that make a difference.

FAQs

1. How do you write a user story step by step?

The process for how to write user stories follows these steps: identify the persona (develop empathy for a specific user), clarify the user’s intent (understand what they want to achieve), connect to the value (why it matters), write in the “As a… I want… so that…” format, add acceptance criteria (conditions of satisfaction), review with stakeholders, split if needed (to fit within a sprint) and estimate effort before adding it to the backlog. This approach ensures stories remain user‑centred and actionable.

2. What are the 3 C’s of user stories?

The three C’s are Card, Conversation and Confirmation. They refer to the written story (card), the discussions that enrich it (conversation) and the acceptance criteria that verify completion (confirmation). Following the 3 C’s keeps stories lightweight but ensures shared understanding and testability.

3. What are the 5 components of a user story?

While the classic format focuses on three parts (who, what and why), mature stories often include five components: a title (a concise summary), a persona, a desire or goal, a benefit or why, and acceptance criteria. Some teams also track story points or definition of done, but those are more about planning and quality control than the core narrative.

4. What is the format for a user story?

The standard user story format is: “As a [persona], I want [goal] so that [benefit].” Atlassian uses examples such as “As Max, I want to invite my friends, so we can enjoy this service together”. This simple structure ensures you capture who the story is for, what they need and why it matters.

.avif)