Product Concept Development Stage (2026)

Discover which stage of product development focuses on concept creation and how concept development shapes successful products.

Launching a new product is hard work. You have an idea and enthusiasm, but when should you firm up the concept? Choosing the right moment in which stage does one develop a concept for a product or service can mean the difference between a focused build and months of wasted coding. I’ve seen promising ideas falter because teams skipped this critical phase. Here I explain why timing matters, where concept development fits within the product life cycle and share practical guidance based on research and my work with startups.

Where concept development sits in the product life cycle?

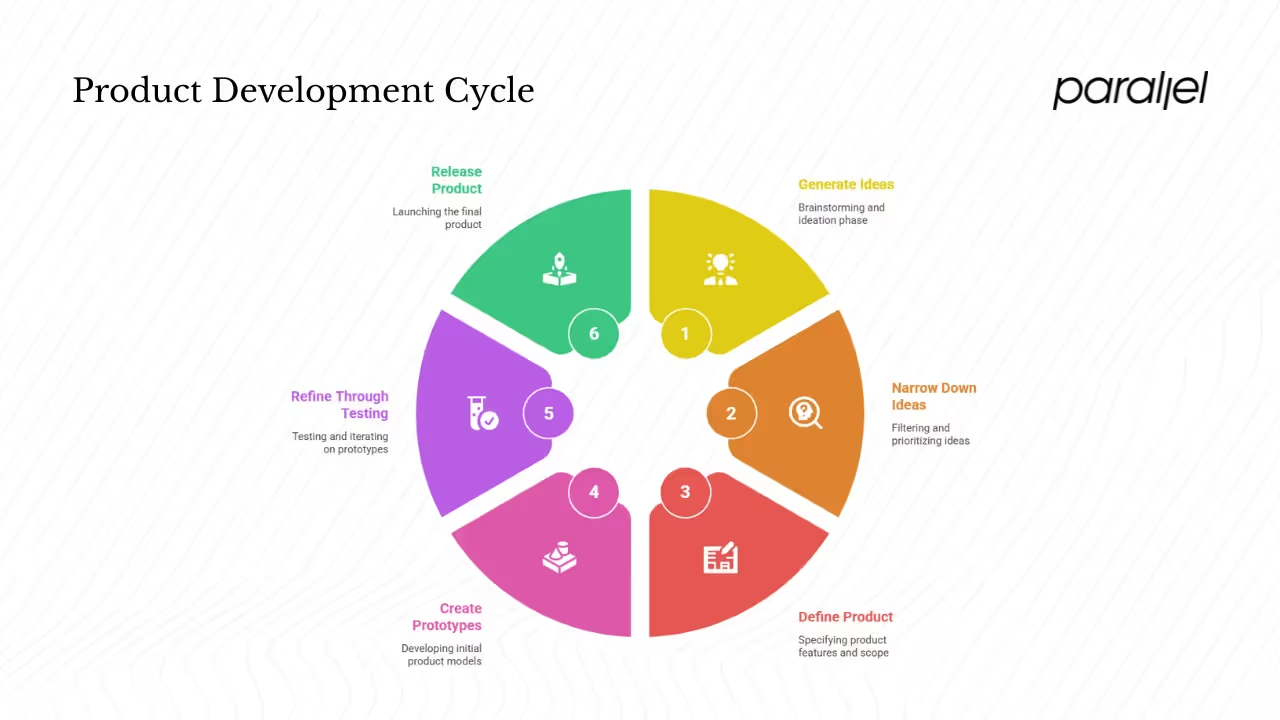

Product teams follow a variety of life‑cycle models. Some use five phases, others six or seven. Regardless of the framework, the core activities remain similar: coming up with ideas, narrowing them down, defining what to build, creating prototypes, refining through testing, and finally releasing a finished product. The differences lie in how finely each stage is split.

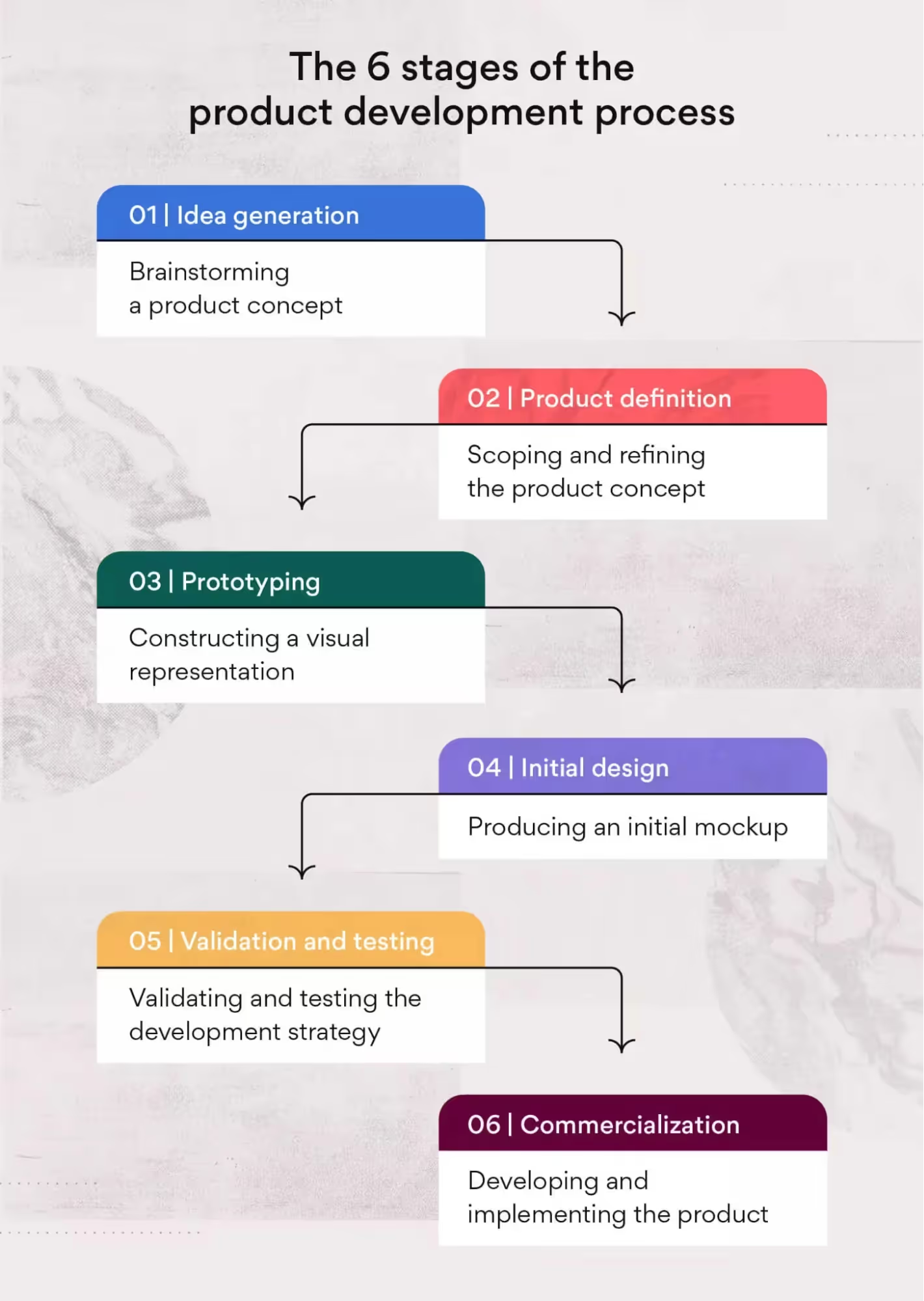

Asana’s six‑stage model: The project‑management company Asana describes six steps: idea generation, product definition (concept development), prototyping, initial design, validation and testing, and commercialization. After generating and screening ideas, teams move into scoping: this stage is about fine-tuning the product strategy, mapping distribution, refining the value proposition and clarifying success metrics. Only once these elements are clear do they start building prototypes.

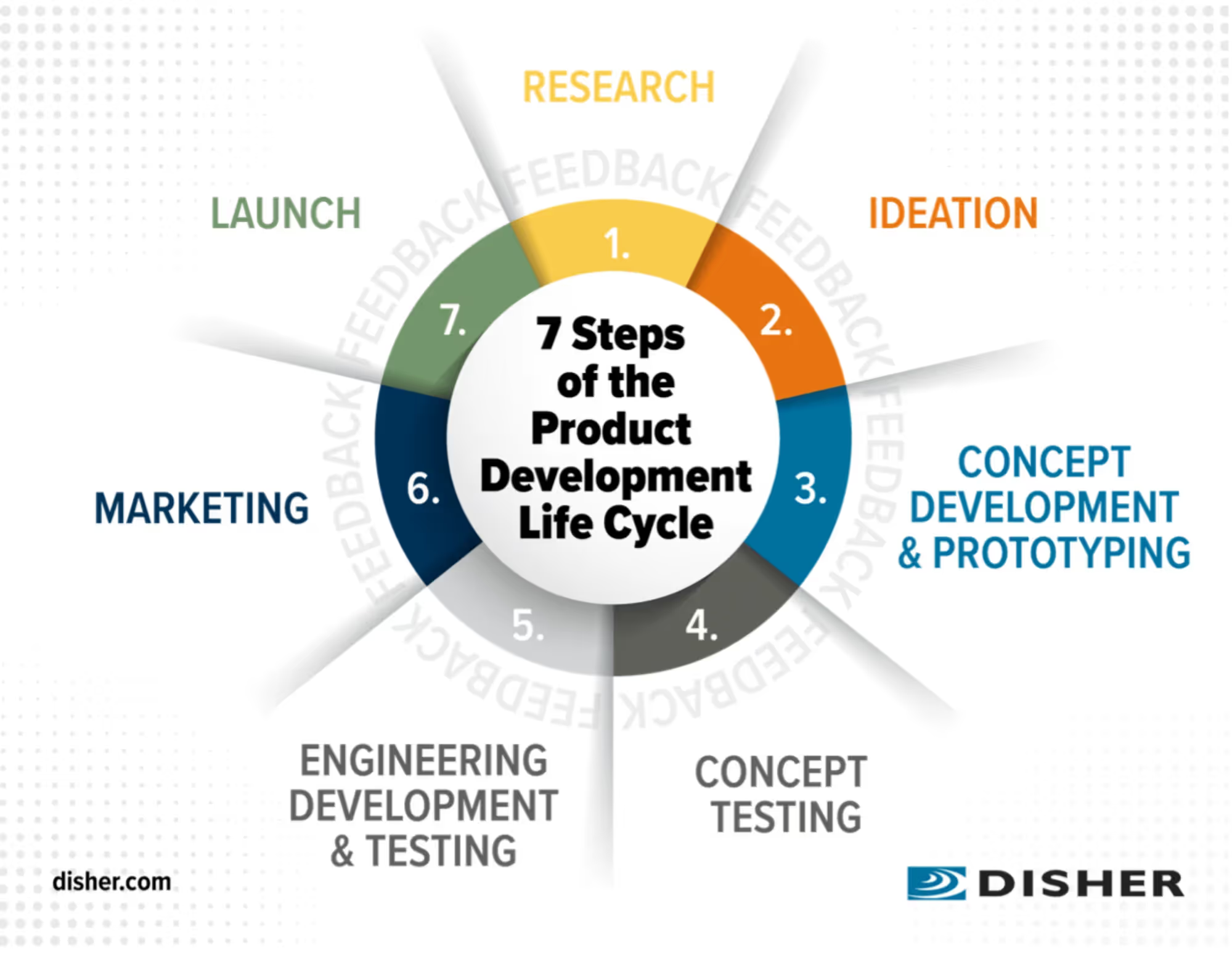

DISHER’s seven‑stage process: Product consultancy DISHER lays out research, ideation, concept development and prototyping, concept testing, engineering and testing, marketing and launch. They stress that concept development follows ideation and involves minimal viable models to evaluate design and functionality.

Many frameworks exist because teams slice the work differently. Hardware products may need extra stages, while software teams often combine steps. Yet they all follow the same arc: generate and screen ideas, then develop the concept and then build prototypes.

The central question: in which stage does one develop a concept for a product or service?

When founders ask me in which stage does one develop a concept for a product or service, I point to the phase that follows ideation and screening but precedes prototyping. Whether you use a five‑stage, six‑stage or seven‑stage model, concept development sits in the middle. You shouldn’t jump straight from brainstorming into building. Instead, you use the concept development stage—sometimes called product definition—to clarify what you’re building, for whom, and why.

Different frameworks emphasise this point. Asana’s “product definition” stage is where you map out distribution, refine the value proposition and set success metrics. DISHER’s process names the stage “concept development and prototyping,” blending conceptual design and early prototypes to test viability. Design2Market’s second stage—concept development and feasibility analysis—tasks teams with defining essential features, assessing market fit and competitive positioning.

Signs you’re ready to develop a concept

Knowing in which stage does one develop a concept for a product or service is important, but you also need to recognise the signals that you’re ready to move into this phase:

It’s time to develop a concept when you’ve narrowed down to a promising idea, confirmed there’s a real problem through conversations or data, gained a basic grasp of who your customers are and what competitors offer, and ensured that the essential members of your team agree on the overall direction.

What happens during concept development

Concept development isn’t a single activity. It’s a set of tasks that turn a rough idea into something the team can prototype. First you keep brainstorming: techniques like SCAMPER and user interviews help you refine or expand your original thought. Then you check feasibility through quick research. Asana suggests business and competitor analysis, while DISHER advises customer interviews and patent searches. Slickplan frames this step as understanding your customer and defining the market.

With this insight, sketch a basic business model outlining your value, likely costs and revenue potential; this doesn’t need precision, but it helps set expectations. Next, visualise the experience with rough sketches or wireframes and, if needed, minimal viable models to assess shape and functionality. Throughout, gather feedback from potential users and stakeholders and adjust. Concept testing—through surveys or simple prototypes—helps catch weak points early. Finally, decide on the minimum set of features for your first build and outline who will do what and when. This prepares you to move into prototyping with confidence.

Why concept development matters for startups and small teams

Every founder is eager to build. The temptation to jump from brainstorming straight to coding is strong—in particular for technical teams. But skipping the concept development stage is risky. According to startup failure statistics compiled in 2025, up to 90% of startups fail and 34% of small businesses that shut down lacked a proper product–market fit. These numbers show clearly the need to validate your concept before investing time and capital. Good concept development reduces the chances of building something nobody needs and helps manage risk.

Structured concept development also lets you practise user‑centred design. The Nielsen Norman Group’s design thinking model moves from empathy to defining the problem, ideating, prototyping, testing and implementing. By taking time to understand user needs and iterating before building, you create better products and avoid costly pivots.

Knowing in which stage one develop a concept for a product or service isn’t just a theoretical concern. It’s a guardrail that keeps your team from rushing ahead or spinning in circles. When everyone agrees on the timing, you can plan resources properly and avoid costly re‑work later.

A clear concept also brings the team together. When I’ve worked with founders who invested time in defining their concept before prototyping, engineers and designers were able to make trade‑offs without endless debates. Investors and stakeholders could see the opportunity, which made fundraising smoother. On the other hand, I’ve seen early‑stage teams skip definition and run into painful miscommunication: engineering built features that marketing didn’t plan to sell, or design focused on aesthetics while ignoring the core problem.

For hardware or regulated products, concept development can prevent expensive rework. Legal or compliance checks, supplier partnerships and supply‑chain planning all have long lead times. Addressing them early avoids last‑minute surprises. Even for web‑based products, early design and testing can surface performance or accessibility issues that are less expensive to fix when the product is still malleable.

Challenges and common pitfalls

As with any process, concept development is not foolproof. Here are pitfalls I’ve observed when mentoring product teams:

- Over‑investing too early: Spending months on detailed design before proving demand wastes resources. Keep sketches rough and prototypes lean.

- Inadequate research: Relying solely on your own assumptions leads to wrong conclusions. Schedule user interviews and competitor checks early.

- Confirmation bias: Falling in love with your idea and ignoring negative feedback undermines the purpose of concept development. Seek out contradictory evidence.

- Scope creep: It’s easy to pack too many features into the concept. Stay focused on the core value; additional features can come later.

- Team disagreements: Without clear documentation, different people may interpret the concept differently. Use one‑page briefs or canvas templates to keep everyone on the same page.

Best practices for strong concept development

Drawing from research and my own practice, here are some methods to make concept development effective:

- Iterate quickly: Borrow from lean and agile methods. Move in short cycles—draft, test, refine. Avoid long planning periods without feedback.

- Engage stakeholders early: Invite engineers, designers and prospective users into workshops and review sessions. Their perspectives will surface issues you might miss.

- Keep the concept flexible: The point of this stage is to try different directions. Avoid locking yourself into a specific solution too soon.

- Focus on the core problem and value proposition: Resist the urge to add “nice‑to‑have” features. Start by solving the most pressing pain point and expand from there.

- Validate with real users: Even simple surveys or unpolished prototypes can reveal whether people understand and value your concept. DISHER emphasises concept testing to evaluate desirability.

- Define success metrics: Asana suggests clarifying metrics early. Decide how you’ll know the concept has potential—sign‑ups, engagement, willingness to pay—and monitor these signals.

Concept development is also a team sport. The Nielsen Norman Group explains that design thinking draws on collective expertise and creates a shared language. Invite marketing, engineering and support early so that their insights can shape the concept. Not only does this surface hidden risks, it also builds shared ownership of the solution. When people from different backgrounds contribute, concepts become more resilient and user‑centred.

Case examples from the field

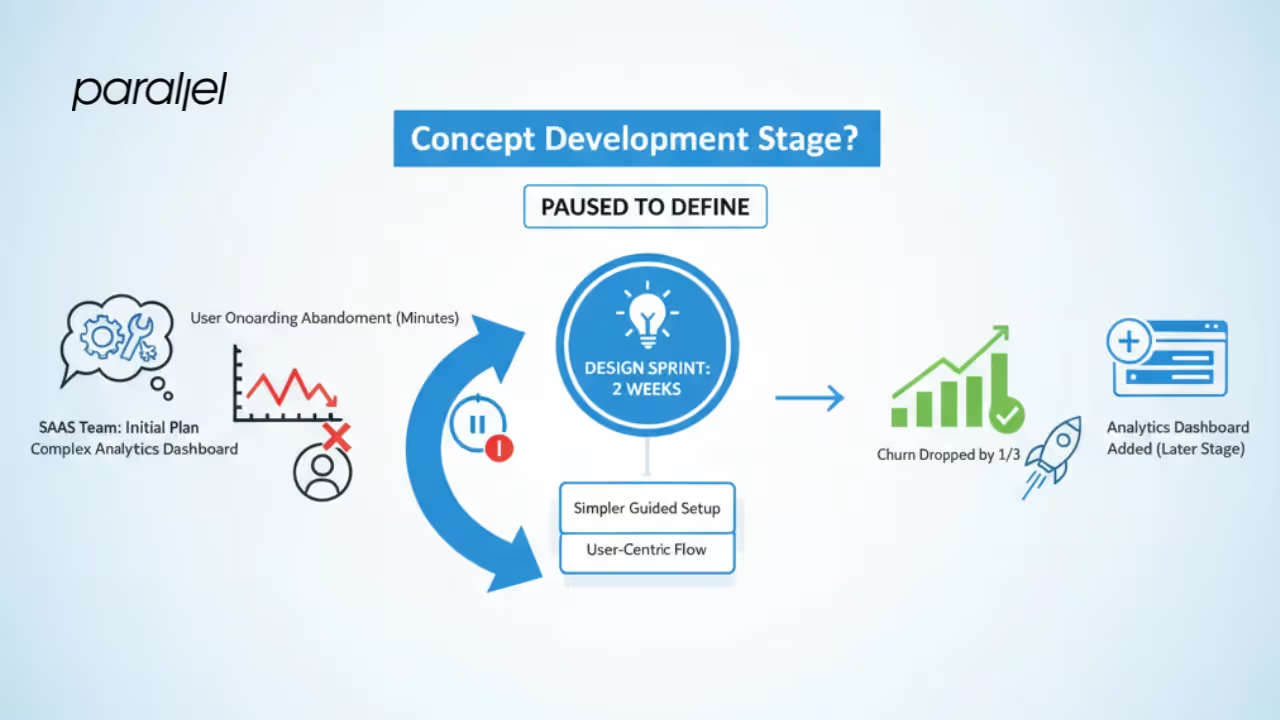

A SaaS team that paused to define

A SaaS client wanted to build a complex analytics dashboard. User interviews showed that new customers abandoned onboarding within minutes. The team paused, asked in which stage one developed a concept for a product or service, and spent two weeks designing a simpler guided setup. Churn dropped by a third, and they added the dashboard later once the core flow worked.

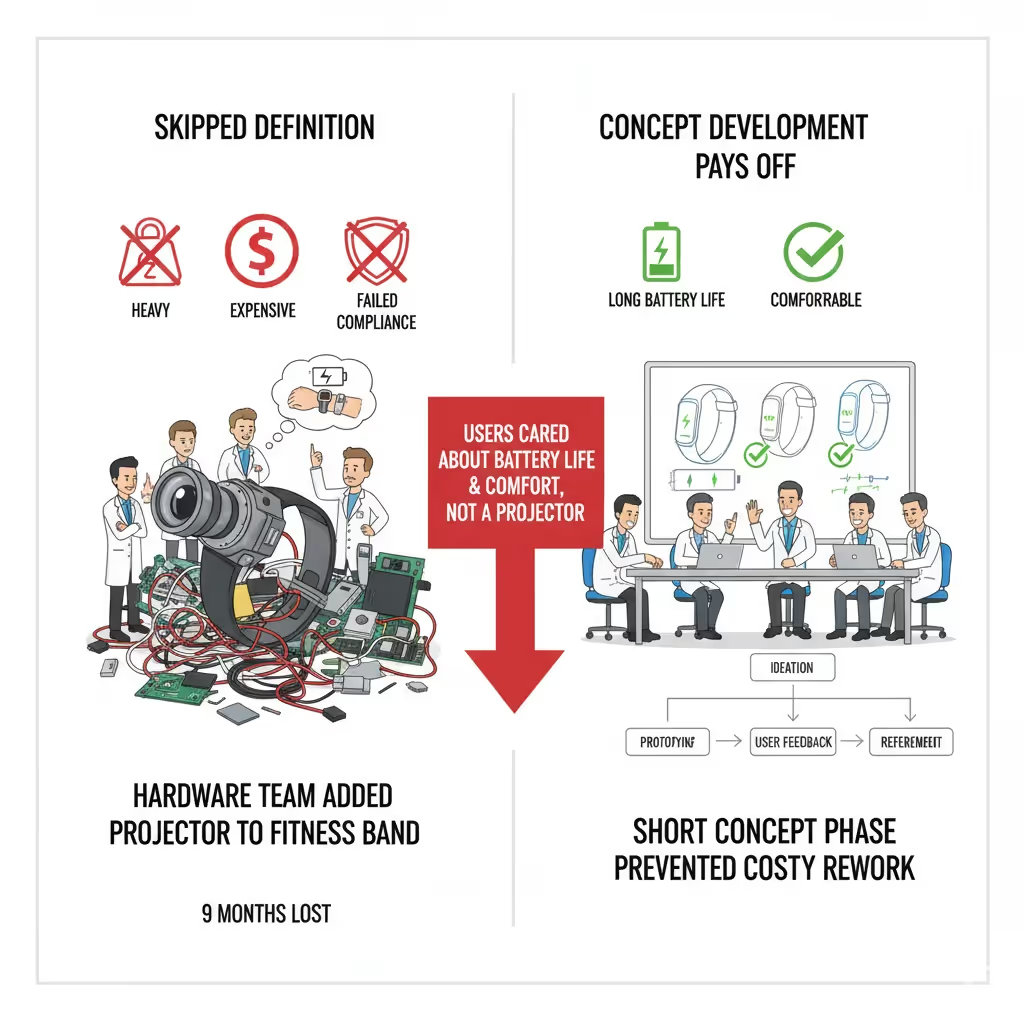

A hardware team that skipped definition

A consumer electronics team added a built-in projector to a fitness band without first defining the concept. After nine months the device was heavy, expensive and failed compliance tests. Users cared about battery life and comfort, not a projector; a short concept development phase could have prevented the costly rework.

Conclusion: make concept development deliberate

Concept development is not an optional “nice to have.” It’s the bridge between brainstorming and building. Across multiple frameworks—from Asana’s six stages to DISHER’s seven and Design2Market’s nine—the answer to in which stage does one develop a concept for a product or service is consistent: after ideation and screening, before prototyping. By investing in research, business modelling, early design and validation, you reduce risk, get everyone on the same page and improve your chances of building something people actually want. Startups operate under enormous uncertainty; a deliberate concept development phase turns uncertainty into informed bets. Take the time to define your concept; it will save you frustration later.

FAQ

1) At which stage does one develop a concept for a product or service?

Concept development happens after you’ve generated and filtered ideas. In most models it’s the second or third stage of the product life cycle—coming after ideation or idea screening but before prototyping and detailed design. During this phase you define the problem, outline essential features, assess market fit and create conceptual designs.

2) What does it mean to develop a concept for a product or service?

Developing a concept means turning a raw idea into a clear plan. It involves understanding your customer, defining their needs, analyzing competitors and market size, articulating your value proposition, sketching out the experience and validating assumptions with early feedback. The output is a documented concept that guides prototyping and development.

3) What are the four stages of product development?

Some companies condense the product life cycle into four broad phases: ideation (or concept development), prototyping (or development), testing and validation, and launch. This simplification still captures the essence of the process. You first decide in which stage one develops a concept for a product or service, then build and test prototypes, refine based on feedback and finally bring the product to market. Even in four‑stage models, you still need to define the concept before you start building.

4) What is the concept phase of product development?

The concept phase—also called product definition or scoping—is where you refine ideas, study your market, model the business, create rough designs and validate assumptions. It is a structured effort to answer in which stage one develops a concept for a product or service. Rather than building immediately, you gather data, collaborate with stakeholders and check feasibility. Done well, it sets the foundation for efficient prototyping and successful launch.

.avif)