Is Product Management a Good Career? Pros, Cons & Skills

Discover if product management is the right career for you. Get an honest look at PM salaries, growth opportunities, and common challenges for 2026. Start reading!

Is product management a good career? That question sounds simple, yet when you’re building a company or stepping into your first product role it can feel like standing at a cross‑roads. Demand for product managers remains high — Product School counted more than 26,000 product‑manager roles posted on LinkedIn each week in the United States at the start of 2025 — and the pay can be very attractive. At the same time the field is changing fast and the shine has worn off for some.

As someone who works closely with early‑stage founders and product teams at Parallel, I’ve seen both sides: the excitement of shaping a product vision and the exhaustion that comes with trying to juggle competing demands. In this article we’ll unpack the appeal and the pushback, weigh the upside and the downside, and share a few strategies for succeeding in product management without burning out.

Is Product Management a Good Career? (2026)

Quick Answer: Yes — product management can be a strong and rewarding career path, but it depends on your strengths and tolerance for ambiguity. The field offers high pay, continuous learning, and leadership potential, yet it also comes with pressure, politics, and unclear career ladders. People who enjoy solving problems across business, design, and technology tend to thrive, while those who prefer predictable routines or well‑defined roles may find it frustrating.

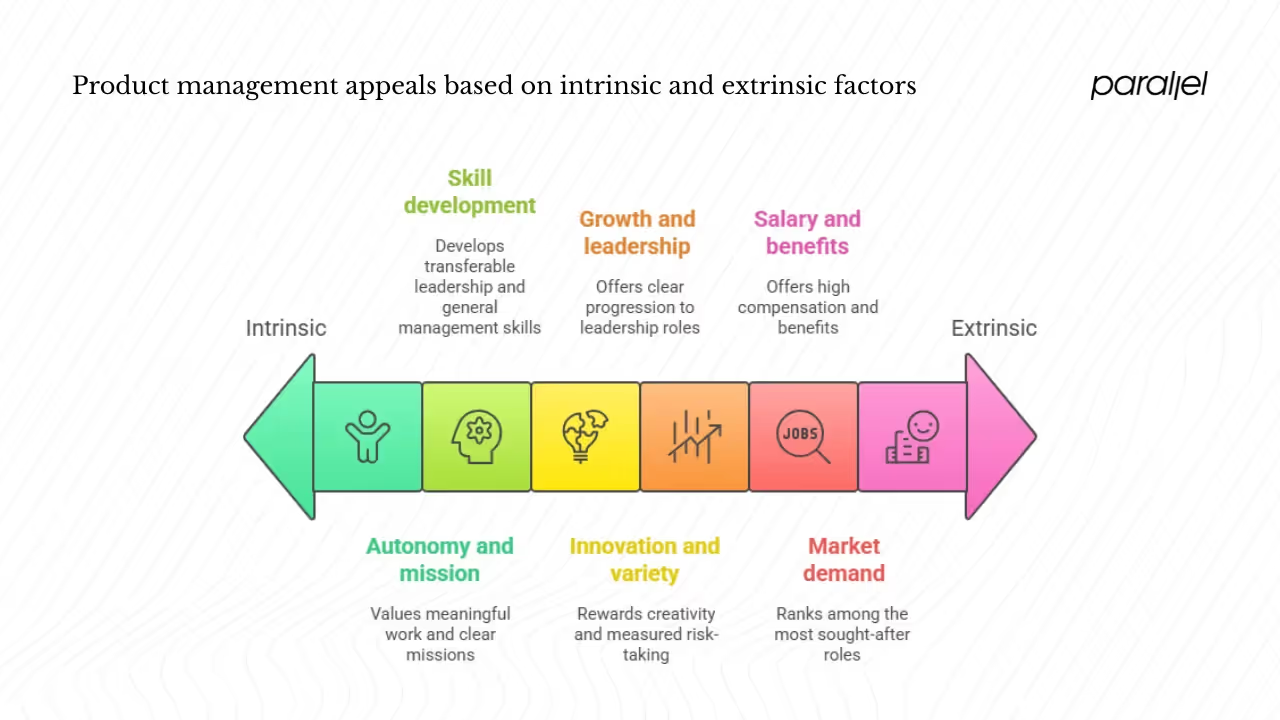

Why product management appeals?

1) Growth and leadership

A key reason people ask is product management a good career? is the promise of growth. At many tech companies product managers are on a path that can lead to director, vice president or chief product officer. Product School’s 2024 salary bands show a clear progression: associate product managers averaged about $86,000 per year, mid‑level product managers around $126,000 and vice presidents of product about $199,000. Those numbers tell a story — product management can pay well at every stage and the ceiling is high. For founders, a great product leader can eventually become a CEO because they hone cross‑functional thinking and gain exposure to all parts of the business.

2) Innovation and variety

Another reason people think about whether product management is a good career is the variety. Product managers sit at the intersection of engineering, design and business. They define problems, shape strategy and work with designers and engineers to build and ship. In our work with software and machine‑learning startups, I’ve seen PMs act as connectors, translating market needs into experiences that customers love. The role rewards creativity and measured risk‑taking. You get to discover unmet needs, prioritise features, run experiments and watch your decisions become real products.

3) Skill development

Good product managers never stop learning. To be effective you need to communicate clearly, analyse data, empathise with users and manage stakeholders. Product managers spend roughly half of their time firefighting unplanned issues, so being organised and resilient is essential. Over time you learn to make trade‑offs, build consensus and accept that perfect information rarely exists. Those skills are transferable to many leadership roles; it’s why product management is often described as a general management training ground.

4) Market demand

Market demand has been a big draw. Product managers rank among the most sought‑after roles in the tech industry. Glassdoor listed the job as the fourth best in the United States in 2023. At the beginning of 2025 there were more than 26,000 open product‑manager roles in the U.S., and Product School’s survey of 7,000 product managers found that many were seeking salary increases. Even with recent tech layoffs, those numbers show that experienced PMs remain in demand.

5) Salary and benefits

Money isn’t everything, but compensation does matter. Product School’s salary data reveals that senior product managers averaged around $152,000, group product managers $195,000 and chief product officers $232,000. Median salaries vary by region — a survey compiled by UXCam reported average U.S. pay around $111,000, €66,000 in Germany and about $37,000 in India. The top ten percent earn over $153,000 and certain roles at companies like Google or Slack can top $200,000. These numbers, combined with equity and bonus potential, make the role financially appealing.

6) Autonomy and mission

People also choose product roles because of autonomy and purpose. Product School found that managers seek more than pay: they want hybrid or remote work, mental‑health support and workplaces that are positive and accepting. They also value meaningful work and clear missions. At startups you may report directly to the CEO, giving you autonomy and influence. ProductPlan’s survey showed that product managers at small‑to‑medium businesses rated their happiness slightly higher than their enterprise counterparts and 38% reported directly to the CEO, giving them an unfiltered view of strategy and more say in decisions.

The real challenges

1) Stress and satisfaction

Answering the question is product management a good career? also means facing its pressures. ProductPlan’s survey found that product managers rated their happiness at 3.8 on a 5‑point scale and that only nine percent were unhappy. That sounds pretty good, but the same study highlighted the sources of frustration: 28% cited internal politics, 25% disliked reacting to problems instead of following a proactive strategy and 21% said a lack of resources was the worst part of their job. Fourteen percent said the work is emotionally taxing and seven percent felt overwhelmed by time constraints. The reality is that product roles are demanding. You’re accountable for decisions without always having formal authority and you’re judged by outcomes you can’t fully control.

2) Work‑life balance

The workload can be punishing. Product managers often work long hours and must context switch between strategic planning and urgent issues. Product School’s research stresses that while salary is important, managers also prioritise work‑life balance, hybrid or remote work and employers who care about mental health. In practice, many PMs set boundaries to avoid burnout; I’ve met plenty who block time for deep work and decline meetings that don’t serve their goals. But the culture of constant availability persists, and some cope by emotionally distancing themselves from the products they manage.

3) Role dilution and confusion

Over the past decade the product role has splintered into specialised titles — growth PM, product owner, platform PM, product marketing manager — which has created confusion. Jeff Gothelf laments that dividing responsibilities between product managers, product owners and business analysts reduces collaboration and clarity. He describes teams where information flows through multiple intermediaries, slowing delivery and hiding the customer’s voice. Gothelf argues that anyone who defines product vision, understands the market and leads the creation of value is a product manager. Marty Cagan adds that the rise of product owners trained by “agile coaches” who have never built products has harmed the craft, and he warns that leaders frustrated with under‑skilled product owners might scrap the role altogether. For people entering the field it can be hard to know what a job titled “product manager” actually entails.

4) Stagnation and layoffs

The hype around product management peaked between 2015 and 2020. Since late 2022 tech companies have cut staff, and product roles haven’t been spared. Mind the Product’s 2024 research reports that the number of open product‑manager roles fell to under 24,000 globally by September 2024. The same article notes that LinkedIn job postings regularly receive hundreds of applications, and some receive thousands. With so many candidates, employers can afford to wait for someone with exactly the right mix of skills and domain knowledge. Because there isn’t a single educational pipeline, many qualified people compete for few openings, and some take roles below their experience level just to stay employed.

5) Recruiting barriers

Getting into product management is harder than it used to be. Mind the Product points out that the mix of applicants ranges from unqualified to highly qualified, so even strong candidates can be screened out by automated systems. Applicant Tracking Systems and easy‑apply buttons have reduced the friction of applying, but they have also increased volume and extended time‑to‑hire. The result is a paradox: there are many experienced product managers on the market and open roles remain, yet it still takes months to land a job. For those trying to break in, the lack of a well‑defined path only makes matters worse.

6) Lack of clear path

Unlike medicine or law, there is no single degree or certification that guarantees you a product role. People come from engineering, design, marketing, data and even operations. That diversity of backgrounds is part of what makes product management interesting, but it leaves newcomers wondering where to start. According to UXCam’s analysis, 60.3% of executives admit they only partially understand the value product managers bring, which suggests that companies themselves aren’t always sure how to develop product talent. Many managers spend more than half their time on firefighting and say that competing objectives, lack of time and unclear roles are their biggest challenges. Without clear educational standards or career ladders, learning happens mostly on the job.

Balancing the upside and the downside

Who thrives

So, is product management a good career? It depends on the person. People who love context switching and problem‑solving tend to thrive. Successful product managers enjoy working across functions, embrace uncertainty and care deeply about the user. They can tell a story that connects customer needs to business goals, and they’re willing to make tough trade‑offs when resources are scarce. They also tend to seek out feedback and adjust quickly. In my work with SaaS founders, the PMs who shine are the ones who can switch from a design review to a sales call to a data deep dive without losing focus. They’re comfortable being wrong and adjust fast when evidence points in a new direction.

Who might struggle

If you crave clear boundaries, dislike conflict or prefer to specialise deeply in a single function, product management might feel uncomfortable. The lack of standard processes means that you’re constantly figuring out “what good looks like” for your context. Product management is filled with ambiguity — the roadmap is always shifting, users surprise you, and executives change priorities. People who prefer a predictable checklist may find the role draining. In our practice we sometimes see designers or engineers moved into product roles by accident; if they don’t actually want to manage trade‑offs and negotiate with stakeholders, they struggle. There’s nothing wrong with preferring to stay close to the craft of design or engineering.

Launching pad

Even if you decide not to stay in product forever, the skills you gain make it a strong launchpad. Product managers learn to ask hard questions, synthesise input and make decisions with incomplete data. Those skills translate to strategy, operations, consulting or founding your own company. The role also exposes you to how a business actually runs — from customer acquisition and retention to pricing and support. Many ex‑PMs become founders or move into growth or operations roles precisely because they understand the entire lifecycle of a product. A stint in product can therefore be a stepping stone to many other paths.

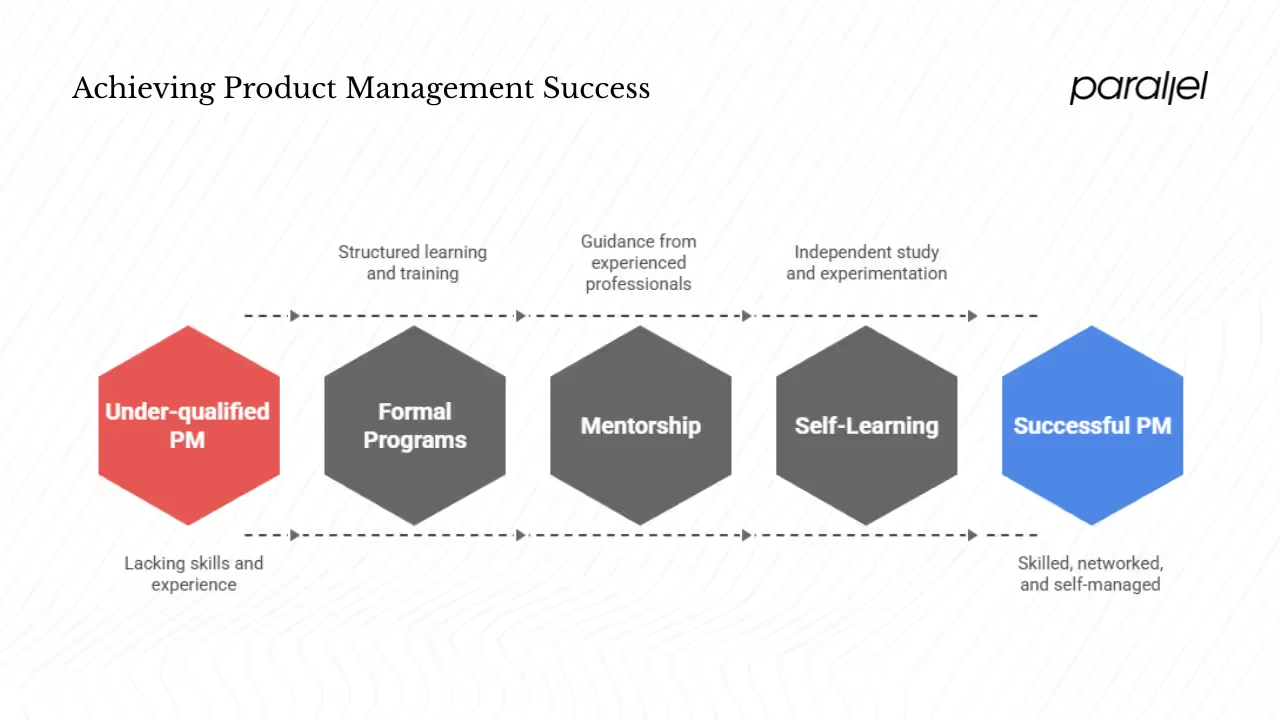

Strategies for success

1) Build the right skills

One reason people wonder is product management a good career? is fear of being under‑qualified. The best antidote is to build genuine skills. Formal programs can help, but they’re not a prerequisite. Product School suggests that only 35% of companies have mature content or training programs, so it’s often up to you to find learning opportunities. Look for courses or certificates that focus on real‑world projects. Seek mentors who have built products similar to yours. Read widely — not just about product management but about psychology, data, and business models. Use analytics tools, run experiments and talk to users yourself. The more you can demonstrate your ability to ship results, the more attractive you become.

2) Grow your network

Community matters. The product job market is crowded, and many roles are filled through connections. UXCam notes that personal networks are the top recruitment source for product managers. Joining communities, attending meetups, participating in design or product conferences and engaging in discussions can open doors. At Parallel we encourage our clients’ PMs to share what they’re learning with peers and to contribute to open forums; this builds visibility and trust.

3) Seek the right environment

Not all product roles are created equal. ProductPlan’s study shows that PMs at small and medium‑sized companies report slightly higher happiness and more direct access to leaders. These roles often offer broader scope because there are fewer people to share the work. Bigger companies can provide resources and structured mentorship, but they may also involve more politics and slower decision‑making. When choosing, think about the trade‑offs: Do you want autonomy or formal training? Do you prefer to own a narrow piece of a huge product or work on everything in a smaller team? There is no one right answer; the right fit depends on your goals.

4) Manage yourself

Success in product management requires self‑management. Prioritise ruthlessly; you will always have more requests than you can handle. Create a clear vision and communicate it often so stakeholders know why some items are off the table. Build relationships based on trust and transparency; they’ll help when you need to push back. Set boundaries for your personal time and take care of your health. Burnout is real, and no product launch is worth sacrificing your well‑being.

5) Think like a founder

Even if you never start a company, thinking like a founder helps. Founders obsess over whether they are solving a real problem, and they iterate quickly when the answer is no. They manage cash carefully and focus on impact. Product managers who adopt this mindset make better decisions because they weigh trade‑offs like an owner. In our work with early‑stage machine‑learning companies we’ve noticed that when PMs think about the business as if it were theirs, they build simpler products that get to market faster and deliver value sooner.

What’s new for 2026 & beyond

- Core industries where product management roles are growing: tech, healthcare, fintech, retail and manufacturing.

- In India: senior product‑management/senior PM hiring jumped ~42 % year‑on‑year, with leadership roles seeing the biggest growth.

- Salary data (India): 2025 mid‑level PM roles often ₹30‑50 LPA; senior roles ₹65 LPA+; top Director/VP roles > ₹1 crore.

- India salary growth projection: ~9 % growth in 2026 across sectors.

Is Product Management Right for You?

Ask yourself these questions:

✅ Do you enjoy switching between design, engineering, and business topics in a single day?

✅ Are you comfortable with shifting priorities and imperfect information?

✅ Do you like making decisions and taking responsibility for the outcome?

✅ Are you good at communicating across different teams and listening to customers?

✅ Do you find energy in solving messy, open-ended problems?

❌ Do you prefer a clearly defined set of tasks with minimal ambiguity?

❌ Do you avoid conflict or dislike negotiating with multiple stakeholders?

❌ Do you prefer to specialize deeply in one technical or creative skill?

❌ Do you feel drained by meetings, trade-offs, and context switching?

Conclusion

So, is product management a good career? The answer is complicated. On the plus side, the role offers meaningful work, steady pay, continuous learning and a path to leadership. It calls for creativity and allows you to shape products that help people. Demand remains high and the salary ranges are competitive. Yet there are real challenges: stress, politics, layoffs and unclear career ladders. The role can be thankless when you’re blamed for bad outcomes and ignored for good ones. Some days will feel like you’re spinning plates while everyone watches. The question of is product management a good career comes down to your tolerance for ambiguity and your desire to work across disciplines.

For those who love solving problems at the intersection of user needs and business goals, product management can be deeply rewarding. For those who crave predictability or prefer to specialise, other paths might suit better. As you weigh whether is product management a good career, be honest about what energises you, seek mentors who can guide you and look for environments that let you use your strengths. With open eyes and the right preparation, product management can be a fulfilling path — just not the only one.

FAQ

1) Is product management in high demand?

Yes. At the start of 2025 there were more than 26,000 product‑manager jobs posted on LinkedIn in the United States every week. Demand surged between 2015 and 2020 and remains strong, though competition has increased. Recent layoffs mean more experienced candidates are in the market.

2) Is a product manager role high paying?

Generally yes. Product School’s 2024 salary data shows that mid‑level product managers average about $126,000, senior PMs earn around $152,000 and chief product officers can earn over $230,000. However, pay varies widely by company, location and stage. Compensation alone doesn’t offset stress or lack of support.

3) Can you make a lot of money in product management?

You can. Top performers in the United States earn more than $153,000 and some roles at companies like Google and Slack exceed $200,000. Equity and bonuses can amplify earnings. Yet high pay often comes with high expectations and long hours. Consider the trade‑offs.

4) Who should not become a product manager?

People who dislike ambiguity, avoid conflict or prefer clearly defined tasks may find product management draining. The role demands constant prioritisation, negotiation and resilience. If you enjoy specialising deeply in design or engineering without juggling business and market pressures, you might be happier staying in those disciplines. The path into product management isn’t well defined, so if you prefer a structured profession with clear qualifications, the answer to is product management a good career for you may be no.

.avif)