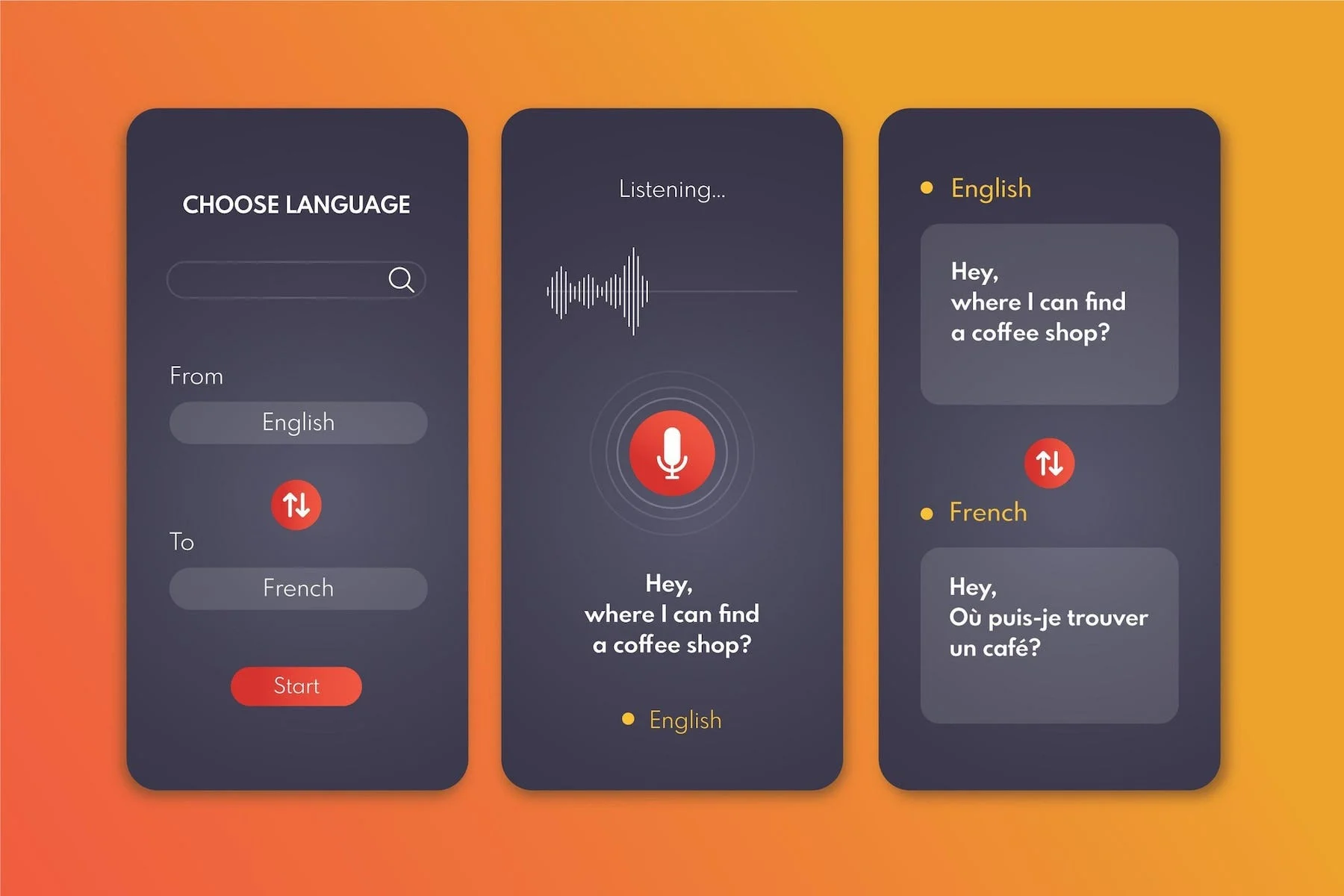

Voice User Interface (VUI) Design Principles: Guide (2026)

Understand VUI design principles, including conversational structure, feedback, and accessibility for voice‑driven interactions.

Voice user interfaces (VUIs) let people speak to computers, phones or speakers and get things done without touching a screen. They are no longer science‑fiction gadgets; there were roughly 8.4 billion voice assistants in use by the end of 2024 and more than 20 percent of internet users now use voice search. Smart speakers, cars and mobile assistants have made hands‑free interaction part of everyday life. For founders and product leaders, the rise of voice is both an opportunity and a challenge: the interface feels natural, yet poor design quickly frustrates users. This article offers a set of voice user interface (VUI) design principles and shows how to apply them. It draws on research from leading design authorities and our experience at Parallel building products with early‑stage teams.

Understanding VUI versus traditional UI

In a graphical interface users rely on persistent visuals, pointers and gestures to move through menus and screens. VUIs, by contrast, are spoken; a user issues a command, the system listens, interprets the intent using speech recognition and language processing, performs an action and responds using audio. Interacting by voice can be faster—speaking a sentence often takes less time than tapping through multiple screens—yet it lacks the persistence of a screen. Users cannot glance at a list of options; they must hold information in memory and mentally map the conversation flow.

Designing VUIs therefore requires a different mental model. Navigation needs explicit cues to show what commands are possible and whether the system is listening. Nielsen Norman Group describes the “Gulf of Execution”: people must know what actions they can take and understand the results. Without visual signifiers, audio cues such as activation tones and spoken suggestions become criticalnngroup.com. Designers must also consider context—voice is often used when a person’s hands or eyes are occupied—and ensure that error states do not leave people stuck.

Understanding these voice user interface (VUI) design principles early will help teams recognise why voice demands different cues, mental models and flows than graphical interfaces.

Under the hood, VUIs rely on automatic speech recognition to turn audio into text and natural language processing (NLP) to parse intents and entities. Advances in these technologies have made voice interactions more accurate and conversational, but misrecognition and ambiguity remain inherent challenges. Good design mitigates these issues through structure, clarity and responsiveness.

Why core design principles matter for VUI

Many of the classic usability heuristics apply to voice, but they need adaptation. Visual interfaces allow users to scan and recover from mistakes easily; spoken interactions are transient and error‑prone. Misinterpretations are more disruptive because people cannot see where they are in a process. UXmatters notes that effective VUIs must understand context, keep interactions simple and handle errors gracefully. Designing for accessibility and personalization broadens the audience: voice is especially helpful for people with visual or motor impairments. At the same time, careless privacy practices or inconsistent prompts can erode trust and lead to costly re‑work.

For startups the stakes are high. Frustrated users may abandon a voice feature faster than a visual one, leaving an early product with poor retention. Investing in thoughtful voice user interface (VUI) design principles up front—rather than bolting voice onto existing screens—saves time later and differentiates your product. In our work with AI‑powered SaaS teams at Parallel we’ve seen that aligning on a few core principles helps small teams prototype, test and iterate voice experiences efficiently.

Applying these voice user interface (VUI) design principles is not simply a matter of aesthetics; it directly affects whether people feel empowered or frustrated when they speak to your product.

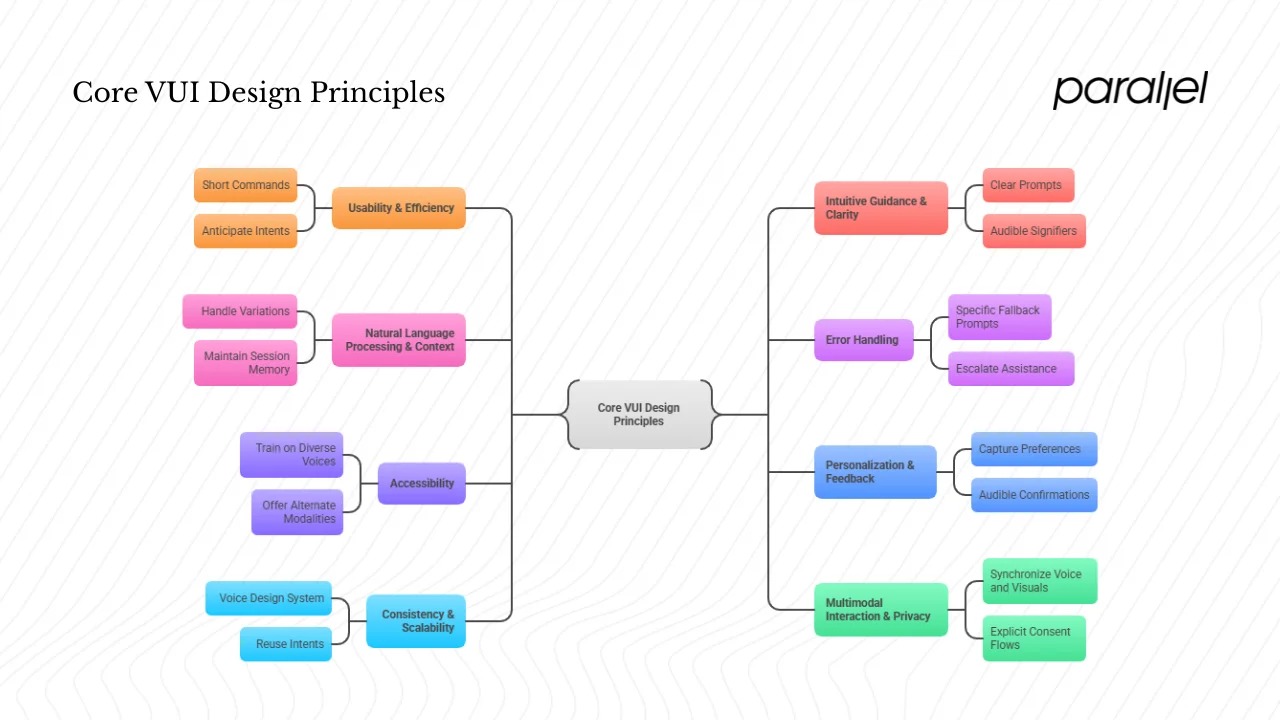

Core VUI design principles

The following eight principles map to critical aspects of voice design. For each principle you’ll find a definition, rationale, practical tips and considerations for lean product teams.

1) Usability & efficiency

Usability in a voice context means that a person can accomplish a task through speech without undue effort. Efficiency means accomplishing that task quickly—minimizing the number of turns, clarifications and cognitive load. Voice can be faster than typing: UXmatters observes that voice commands can improve task efficiency. Yet, unlike a screen, voice outputs vanish instantly. Long prompts or convoluted command structures force users to keep too much in their head.

Tips for usability and efficiency:

- Keep voice commands short and natural. Replace a multi‑step form with a concise question, e.g., “How can I help you today?”

- Anticipate common intents and surface them early; repeated commands such as “check order status” or “play music” should be recognized instantly.

- Measure time to complete tasks with voice versus screen. If it takes longer, simplify the flow or consider a visual fallback. In our projects, prototyping voice flows early and timing them revealed where users stumbled.

- Provide quick confirmations (“Got it”) to reassure users without blocking progress. This echoes the advice from UXPin to combine prompts and statements: ask concise questions and follow with clear statements.

2) Intuitive guidance & clarity in communication

Without a graphical menu, people need to know what they can say. Kathryn Whitenton’s study on audio signifiers explains that systems should offer verbal and non‑verbal cues to help users understand available commands. Non‑verbal cues like chimes signal when the assistant is listening; explicit verbal signifiers suggest possible actions (“You can say ‘set a timer’”). Implicit cues, such as pausing speech when interrupted, mimic human conversation and invite users to speak.

Tips for intuitive guidance:

- Start with a clear opening prompt that describes capabilities. For first‑time users, list two or three common intents to avoid overwhelming them.

- Use everyday language. Avoid jargon and follow natural speech patterns; UXPin stresses that prompts should limit options to a few frequent tasks.

- Mirror the user’s phrasing in responses to build rapport and confirm that you heard correctly.

- Integrate audible signifiers and, when a screen is available, visual hints such as chips or suggestion buttons.

3) Natural language processing & context awareness

Speech recognition converts sound to text, but understanding meaning requires natural language processing. Justinmind describes how a VUI breaks speech into phonemes, recognizes words and uses NLP to map them to intents. Modern assistants use machine learning to handle diverse accents, phrasing and grammar. However, interpreting one command is not enough; effective VUIs remember context across turns. UXmatters emphasises that a VUI must understand user context before responding.

Checklist for NLP & context:

- Expect variations. Design intents to handle synonyms and flexible wording (“order my usual” vs. “repeat my last order”).

- Maintain session memory. If a user asks, “Where’s my package?” and then says, “Will it arrive tomorrow?”, the system should link both questions.

- Capture device and user context. A car assistant knows the user is driving, so it might read messages aloud rather than display them.

- Decide how much context to support. Startups need to balance sophistication with engineering cost; begin with remembering simple parameters (names, dates) and expand as usage grows.

4) Error handling

Errors are inevitable in voice interfaces due to speech recognition gaps, ambiguous commands or background noise. Amazon’s design checklist for error handling advises using plain language, explaining what went wrong, repeating required information and offering context‑specific help. It also warns against blaming the customer or promising features the system cannot deliver. Designlab recommends proactively assisting users by offering alternatives or asking clarifying questions when misunderstandings occur.

Tips for graceful recovery:

- Use specific fallback prompts: “I didn’t catch that. Are you asking for your balance or your last transaction?”

- Escalate assistance on repeated errors. After two failed attempts, switch to a simpler question or suggest ending the task.

- Acknowledge partial information and ask follow‑up questions rather than forcing the user to repeat everything.

- Log error cases and analyze them to improve recognition models and wording. At Parallel we track failed voice interactions to uncover phrasing patterns and refine intents.

5) Accessibility

Voice interfaces can make technology more accessible to people who have trouble using traditional screens or keyboards. Justinmind notes that VUIs enable hands‑free, eyes‑free interaction, benefiting users with visual impairments or motor difficulties. UXmatters lists accessibility among the advantages of VUIs. Yet voice itself introduces accessibility concerns: speech recognition may struggle with accents, speech impediments or background noise, and solely audio responses may exclude deaf or hard‑of‑hearing users.

Accessibility considerations:

- Train on diverse voices and accents. Include speakers from different regions in your testing pool.

- Offer alternate modalities. Provide the option to read responses on a screen or interact via typing, as Apple’s “Type to Siri” feature does.

- Design voice prompts with adjustable speed and volume, and support assistive devices.

- Test with varied user groups early and measure accessibility metrics such as success rate across demographics.

6) Personalization & feedback mechanisms

People expect their assistant to recognise them and adapt. Personalization means tailoring interactions based on user preferences, history and context. The Big Sur AI data set suggests converting top questions into concise answers and recording quick confirmations to keep sessions moving. Voice experiences feel more engaging when the system remembers past actions (“order my usual”) and offers contextual follow‑ups.

Feedback mechanisms give users confidence that the system heard and is acting. Because voice responses vanish, confirmations are vital. UXmatters highlights that capabilities for feedback and confirmation are essential.

Tips for personalization and feedback:

- Capture preferences (frequent orders, names, pronouns) and use them to shorten future interactions.

- Provide audible confirmations (“Okay, ordering a medium latte”) and ask for confirmation before executing critical actions.

- Allow corrections. Let users interrupt to change details, and design flows to accommodate self‑correction.

- Build backend systems to securely store preferences and respect data policies; transparency about how data is used builds trust.

7) Consistency & scalability

As voice capabilities expand, consistent command structures, tone and error responses help users learn and trust the system. UXmatters lists consistency, user‑centred design, continuous testing and accessibility as core best practices for VUI design. Without guidelines, teams risk creating disjointed experiences across different devices or features.

Scalability refers to growing the range of supported intents and domains without degrading usability. As the number of voice assistant devices exceeds the global population, products will span phones, speakers, cars and wearables. Startups should define naming conventions, intent structures and tone early, then reuse these building blocks when adding features.

Planning for consistency and growth:

- Create a voice design system documenting tone, prompt styles, slot naming and confirmation patterns. Share it across teams to maintain coherence.

- Reuse intents across channels; Big Sur AI suggests designing once for phone, speaker and car to reuse the same intents and responses.

- Establish governance: assign a point person to approve new intents and ensure they align with the system’s vocabulary.

- Plan for analytics. Measure completion rates, prompt effectiveness and error patterns to identify where to invest next.

8) Multimodal interaction & privacy/security

Few devices are voice‑only. UXmatters argues that capable VUIs should integrate voice with touch and visual inputs to provide a cohesive experience. Screens can display options or progress while voice handles quick commands. But mixing modalities requires careful coordination: the user should not have to repeat information when switching from voice to screen.

Privacy is another critical concern. Voice assistants continuously listen for wake words, raising fears that personal conversations could be recorded inadvertently. Voice input may expose sensitive data; the design must provide clear controls. Designlab notes that Alexa lets users review and delete recordings and even ask, “Tell me what you heard,” to see what was captured.

Designing multimodal, private experiences:

- Synchronize voice and visuals. If the user speaks, show a summary on screen; if they tap, maintain context in the voice session.

- Offer explicit consent flows. Explain what data is stored and provide easy ways to delete voice recordings or opt out.

- Limit sensitive information spoken aloud in shared spaces. For example, ask whether to send a confirmation to a private device.

- Implement security measures such as voice profiles and passcodes for purchases or account actions.

Applying the principles: a startup‑focused workflow

For founders and product managers, applying these principles requires a structured process. Start by researching the real contexts in which people will use your voice feature. Are they driving, cooking, or managing a business? Interview potential users and build personas that include vocal traits and typical phrases.

Next map voice‑first flows. Identify high‑frequency tasks that voice can simplify, such as reordering a favorite product or controlling a device. Sketch conversation scripts or use voice prototyping tools to simulate dialogs. Include prompts, confirmations, error paths and fallback options. Low‑fidelity prototypes help teams catch awkward phrasing and discover missing intents.

User testing is essential. Recruit participants with varied accents and abilities. Measure task completion rates, number of turns, hesitation time and satisfaction. Compare time to complete tasks via voice versus screen; refine commands to reduce friction. Collect feedback about clarity and trust.

Iterate quickly. Use analytics from real usage to uncover ambiguous intents, frequently misrecognized phrases or privacy concerns. Adjust wording, context handling and error flows. When the feature stabilizes, document your voice design system: tone, prompts, intents, error patterns and data policies. As you add domains, reuse intents and maintain consistency. Monitor metrics such as voice success rate, average turns per task, and user satisfaction. Align privacy practices with regulatory requirements and communicate them clearly.

This startup‑focused workflow puts the voice user interface (VUI) design principles into practice by grounding them in research, prototyping, testing and iteration.

Case study: building a voice ordering flow

Consider a hypothetical food‑delivery startup adding a voice assistant to its mobile app. Users can say “Order my usual” to reorder their favorite meal. The assistant needs to:

- Detect the intent and recognize the phrase despite variations (“Repeat my last order” or “I’ll have the same as yesterday”).

- Confirm the existing order: “Your usual is a medium Margherita pizza. Would you like any changes?”

- Handle modifications. If the user adds toppings, capture them and confirm.

- Offer personalization: remember that the user always orders extra cheese and propose it proactively next time.

- Gracefully manage errors. If the speech recognition mishears “pepperoni” as “peperoni,” ask for clarification.

- Provide multimodal feedback: show the order summary on screen while speaking the confirmation.

This small flow touches several voice user interface (VUI) design principles. It relies on NLP and context to match “my usual”; uses clear prompts for confirmation; personalizes by learning preferences; and handles errors by clarifying toppings. A quick prototype exposed friction: early users hesitated when asked open‑ended questions, so the team rephrased prompts to provide two options. Over several iterations the ordering time fell from 52 seconds to 35 seconds, and user satisfaction improved.

Conclusion

Voice interfaces open new ways for people to interact with products, particularly when their hands or eyes are occupied. Adoption continues to grow: about 20.5 percent of internet users conduct voice searches, and over 100 million Americans own a smart speaker. Well‑designed voice experiences can differentiate a product, extend accessibility and reduce support costs (voice agents can cut support expenses by up to 30 percent). Yet voice is its own medium with unique constraints: transient audio, potential misrecognition and privacy concerns.

For early‑stage startups the takeaway is simple: treat voice as more than an add‑on. Invest in usability, clarity, contextual understanding, error recovery, accessibility, personalization, consistency, multimodality and privacy. Prototype conversations early, test with diverse users and build a design system to scale. By embracing these voice user interface (VUI) design principles from the outset, you’ll build voice features that serve your users well and position your product for the next wave of interaction. These voice user interface (VUI) design principles can become a common language between designers, product managers and engineers.

FAQ

1) How does a voice user interface (VUI) work?

When you speak to a voice assistant, the system captures audio, cleans it, and breaks it into phonemes. It then uses natural language processing to identify words, understand grammar and determine your intent. The assistant executes an action based on that intent and replies using synthesized speech. Modern VUIs use machine‑learning models to handle diverse accents and phrasing. Some devices also display visual confirmation or provide haptic feedback.

2) What are the key principles of user interface (UI) design?

Classic UI principles include clarity, simplicity, consistency, accessibility and feedback. In voice design these principles manifest differently: clarity requires using concise, unambiguous prompts; simplicity means minimizing the number of conversational turns; consistency demands uniform command structures and tones; accessibility involves supporting varied voices and offering alternative modalities; and feedback includes audible confirmations and context retention.

3) What is an example of a VUI design?

A common example is a food‑ordering assistant that recognizes “Order my usual,” confirms the order, allows modifications, handles misrecognition and remembers preferences for next time. It uses clear prompts to suggest options, maintains context across turns and provides visual feedback of the order. If the assistant mishears a topping, it asks a disambiguating question rather than failing. This design illustrates several voice user interface (VUI) design principles, including personalization, error handling and multimodality.

4) What are the seven principles of user experience design?

The often‑cited principles are: useful (serves a purpose), usable (easy to use), desirable (appealing and engaging), findable (easy to locate), accessible (usable by people with disabilities), credible (trustworthy) and valuable (delivers value). In voice design these map to: usefulness by solving real tasks that benefit from hands‑free interaction; usability through short, natural conversations; desirability via a friendly, consistent voice persona; findability by clearly stating what commands are available; accessibility through support for diverse voices and alternative inputs; credibility through transparent privacy practices; and value by delivering faster task completion and wider reach.

.avif)