What Is Acceptance Criteria? Guide (2026)

Learn what acceptance criteria are, how they define done, and their importance in agile product development.

Picture this: a seed‑stage software startup has worked for months on a lean mobile app. When the beta finally launches, reviewers complain about sluggish login flows, missing password recovery links and inconsistent error messages. Inside the team, the developer swears “it worked on my machine,” the designer assumed “a search bar was fine,” and the product manager thought “we’d handle password resets later.” The underlying issue wasn’t talent – it was the lack of shared acceptance criteria. Without clearly defined conditions for success, everyone’s interpretation of “done” differed, and the launch suffered.

This article explores what is acceptance criteria, why it matters for startups, and how to apply it. In plain language: what is acceptance criteria refers to the simple question of the conditions that define when something is “done.” We will cover the concept, its benefits, distinctions from related terms, core traits, common formats, writing practices, and real‑world tips. You’ll finish with a practical toolkit for using acceptance criteria to align teams, improve quality and ship better products.

What is acceptance criteria?

Acceptance criteria are predefined conditions a user story or project deliverable must satisfy to be considered complete and acceptable by stakeholders. In an agile context they describe what successful delivery looks like, independent of how it is implemented. Atlassian notes that acceptance criteria focus on the final desired outcome rather than how to reach a solution. ProductPlan defines them as “predefined requirements that must be met to mark a user story complete”. Dovetail echoes that acceptance criteria are conditions required for the product, user or stakeholder to accept the work, and aqua cloud emphasises that these conditions apply from the entire project level to a granular requirement and bridge the gap between development teams and stakeholders.

Unlike design specifications or implementation tasks, acceptance criteria do not tell developers which libraries to use or how to code a feature. They focus on validating the result. For example, an acceptance criterion for a search feature might state that search results return exact and partial matches; it doesn’t dictate database indexes. This outcome‑orientation allows developers to apply their expertise while providing testers with clear pass/fail conditions.

Acceptance criteria are sometimes conflated with a definition of done (DoD). The DoD is a universal checklist (for example: code reviewed, documentation updated, tests passed) that applies to every backlog item. Acceptance criteria, by contrast, are unique to each user story. They specify how that particular feature must behave to be accepted. Test cases drill deeper by providing step‑by‑step inputs and expected results, whereas acceptance criteria set the high‑level conditions that those test cases verify.

Why acceptance criteria matter in startups

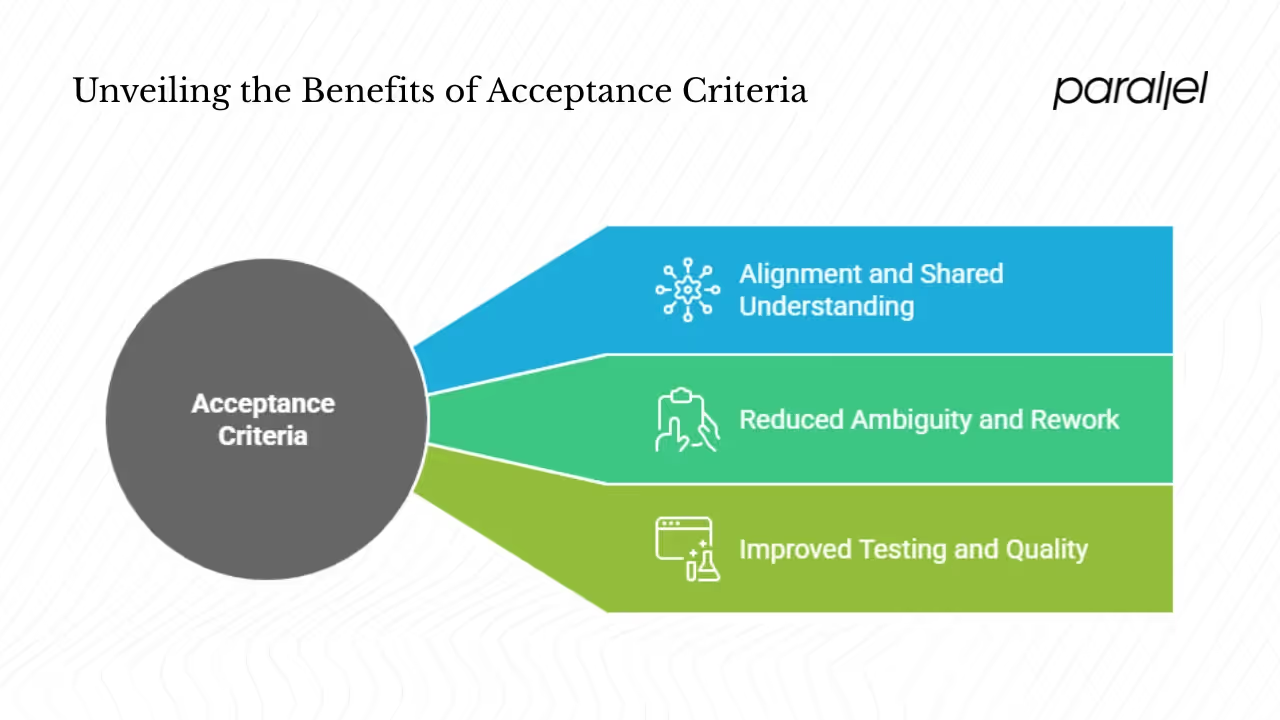

Early‑stage startups operate with limited time, budget and talent. They must move fast without compromising quality. In this environment, acceptance criteria offer three critical benefits:

- Alignment and shared understanding: Atlassian observes that explicitly defining requirements creates a shared understanding among developers, product owners and testers. Dovetail adds that acceptance criteria clarify the user story by outlining expected outcomes, give QA teams definable goals and ensure that everyone is on the same page. When a startup is juggling feature requests, investor demands and technical debt, such alignment reduces misinterpretation.

- Reduced ambiguity and rework: Well‑written acceptance criteria act as completion criteria and a concrete definition of done, eliminating subjectivity. Without them, teams risk discovering mismatches late in development, leading to costly rework. Startups with limited resources cannot afford to build features twice; acceptance criteria help them get it right the first time.

- Improved testing and quality: Clear criteria translate directly into testable requirements. Testers know exactly what to evaluate, from pass/fail scenarios to performance thresholds. Aqua cloud notes that acceptance criteria provide the basis for creating test cases and define specific conditions that must be met, helping startups deliver reliable products even with small QA teams.

Understanding what is acceptance criteria also empowers founders to protect scarce resources. By clearly stating the conditions of success up front, they avoid investing in features that don’t meet stakeholder needs and prevent rework.

Beyond these technical benefits, acceptance criteria can improve stakeholder satisfaction. When customers, investors or leadership know exactly what a feature will deliver, they’re less likely to be surprised by its limitations. In ProductPlan’s 2024 state‑of‑product‑management report, product leaders highlighted a growing emphasis on measuring outcomes rather than output and seeking standardization through product operations. Acceptance criteria align with these trends by anchoring features around outcomes and providing a consistent framework for evaluating success.

Acceptance criteria vs. related terms

User stories and requirements

A user story captures the why and what of a feature: “As a user, I want to reset my password so that I can regain access.” It describes a user’s goal and the benefit. Acceptance criteria, on the other hand, capture the what good looks like, or when done. They translate that goal into measurable conditions. For the password reset story, acceptance criteria might include: a password reset email is sent when a valid address is submitted; clicking the link allows the user to set a new password; the reset link expires after a certain time. Dovetail summarises this distinction: a user story is a high‑level overview focusing on what and why, while acceptance criteria are accepted conditions or rules that add specificity and determine when the story is complete. Scrum Alliance echoes that a user story describes the customer’s need, whereas acceptance criteria describe what should be done to solve their problem. Aqua cloud similarly notes that user stories communicate desired outcomes while acceptance criteria define how to measure completion.

Definition of done

As mentioned earlier, the definition of done is a universal checklist that applies to every backlog item: code must be reviewed, documentation updated, tests passed, etc. Acceptance criteria are unique to each user story. Aqua cloud highlights that DoD is a standardised checklist for quality and consistency while acceptance criteria ensure that specific functionality meets stakeholder expectations. For startups, this distinction is important. You may have a DoD requiring code review and unit tests, but acceptance criteria for a chat feature might include real‑time message delivery, cross‑device synchronisation and a maximum latency threshold.

Test cases and specifications

Test cases are detailed procedures used by testers to verify each acceptance criterion. They include specific inputs, execution conditions and expected results. Specifications describe implementation details, such as database schema or algorithm choices. Acceptance criteria sit between user stories and test cases: they define the high‑level conditions that will later be translated into detailed test cases without constraining implementation.

Core traits of good acceptance criteria

Not all acceptance criteria are equal. High‑quality criteria share several traits:

- Clarity and conciseness: They use plain language so that all stakeholders can understand them. ProductPlan advises keeping criteria simple and straightforward. Avoid technical jargon or vague statements.

- Testability: Each criterion must be demonstrably verifiable. The pass/fail outcome should be objective. Scrum Alliance notes that acceptance criteria are pass/fail and never “partially fulfilled”.

- Outcome‑oriented: Focus on the desired result or user experience rather than the method of implementation. Dovetail emphasises writing criteria from the customer’s perspective.

- Measurable: Where possible, express criteria in quantitative terms (e.g., “page loads in under two seconds” or “search returns at least three relevant results”).

- Independent and specific: Each criterion should ideally be independent of others, allowing isolated testing. Avoid bundling multiple conditions into a single statement.

- Aligned with stakeholders: Acceptance criteria must capture customer requirements accurately. They should reflect consensus among product owners, designers, developers and testers.

ProductPlan adds that effective criteria are clear, concise, testable, and provide user perspective. Scrum Alliance summarises: statements should be clear, concise, testable and focused on providing customer‑delighting results.

In practice, explaining to stakeholders what is acceptance criteria fosters transparency and builds trust. When stakeholders understand the criteria up front, they can align expectations and reduce debates about whether a feature is finished.

Whether you're building an MVP or scaling to thousands of users, knowing what is acceptance criteria helps you anchor discussions around outcomes rather than deliverables. This simple phrase becomes a rallying cry for clarity and shared goals.

Common formats and examples

Scenario‑oriented (Given/When/Then)

This behaviour‑driven development (BDD) style uses the Given/When/Then syntax to describe a scenario. It provides context, action and expected outcome in a natural language structure. Atlassian points out that scenario‑oriented acceptance criteria often mirror test case writing and reduce the time spent writing tests. They are especially useful when behaviour is complex or involves multiple steps.

Example (password recovery flow):

User story: “As a website user, I want to recover my password so I can access my account.”

Acceptance criteria:

- Given the user is on the login page, when they click “Forgot Password” and submit a valid email, then the system sends a password recovery link to that email.

- Given the user follows the link, when they enter a new password and confirm it, then the system updates the password and displays a success message.

Example (ATM cash‑out scenario):

- Given a customer has a valid bank card and sufficient balance, when they insert the card and request to withdraw $50, then the ATM dispenses $50 and updates the account balance.

- Given the balance is insufficient, when the withdrawal is requested, then the ATM displays an “Insufficient funds” message and rejects the transaction.

Rule‑oriented / checklist format

This simpler format lists rules or conditions as bullet points. It works well for user interfaces or features with straightforward requirements. For instance, a hotel search feature might have criteria like:

- Search input is at the top of the page.

- Placeholder text reads “Where are you going?”

- The field supports city, hotel name and street address.

- Input is limited to 200 characters.

Checklists are quick to write and easy to digest. They can be paired with scenario‑based criteria for comprehensive coverage. points out that many teams use bullet lists and place them directly in the user story or ticket.

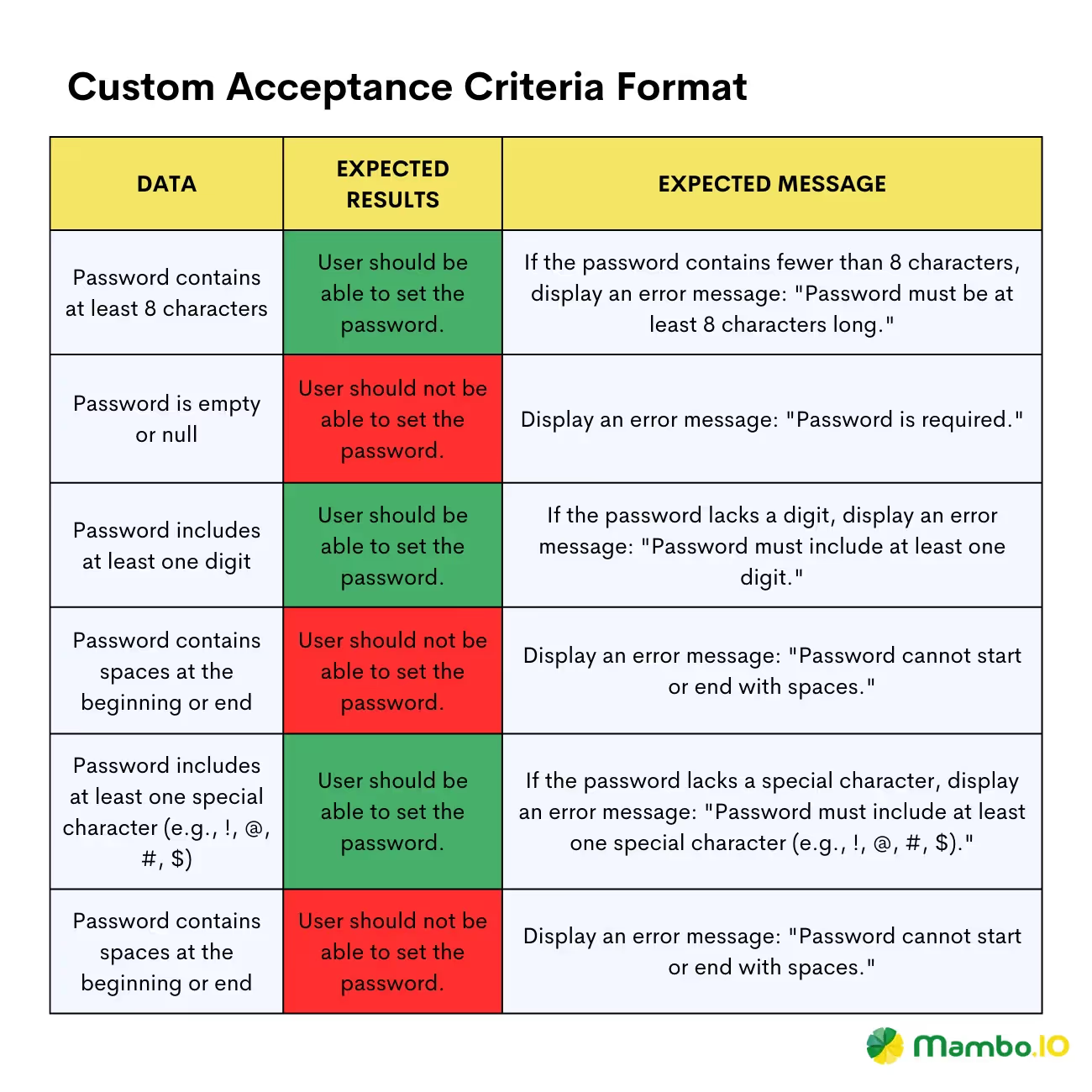

Custom or hybrid formats

There is no single correct format. Dovetail notes that your project’s scope, audience and team skills should inform your choice. Some teams use plain text statements; others create tables or spreadsheets. You can combine scenario‑based and rule‑based criteria or even use diagrams. The key is clarity, testability and shared understanding.

When and who should write acceptance criteria

1) Timing

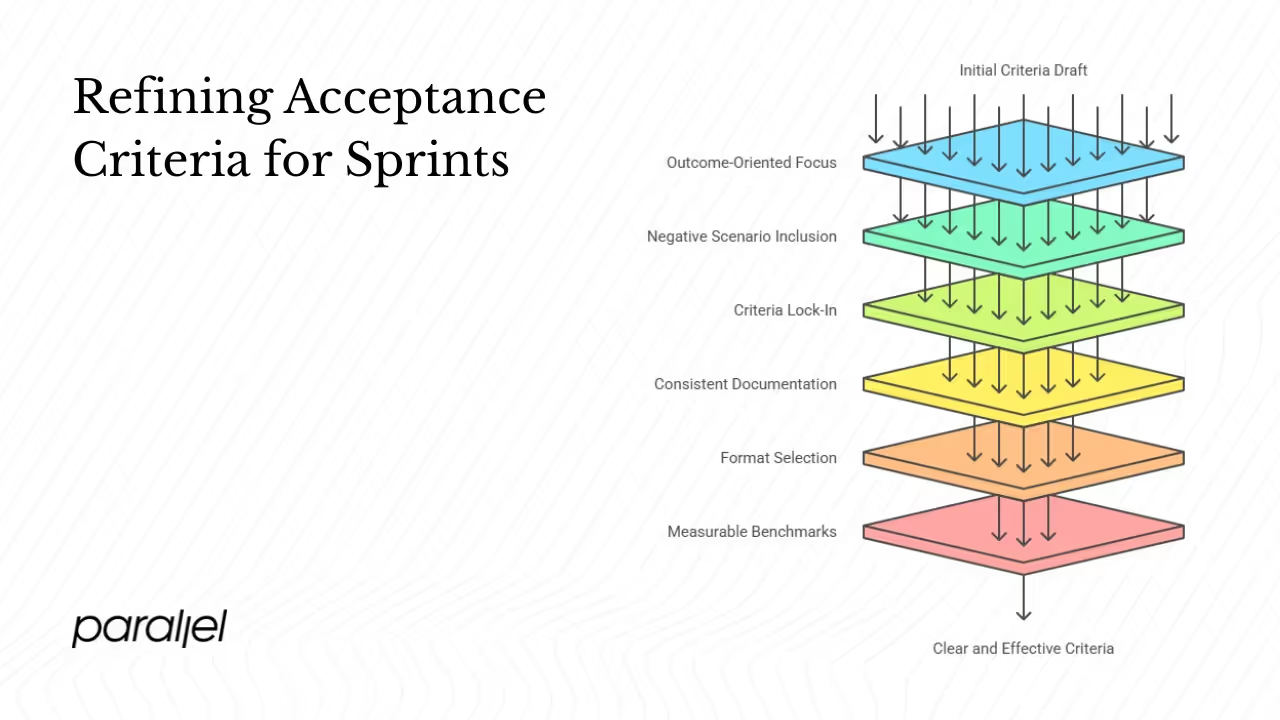

Acceptance criteria should be crafted during backlog refinement and finalised just before development begins. Scrum Alliance recommends identifying initial criteria during refinement and finalising them during sprint planning. Writing them too early risks wasted effort if priorities shift, while writing them too late leads to ambiguous delivery. “Just‑in‑time” criteria ensure the latest information, including customer feedback, is incorporated.

2) Responsibility

While anyone on a cross‑functional team can draft acceptance criteria, the product owner or product manager often initiates the process. ProductPlan notes that product managers are typically responsible for writing criteria or facilitating the discussion. Dovetail echoes that product managers or product owners should be familiar with acceptance criteria and may write them.

However, collaboration is key. Atlassian points out that a collaborative approach involving product owners, development team and a Scrum master results in a comprehensive set of criteria. aqua cloud lists roles such as product owners, business analysts and stakeholders who should participate to ensure alignment. QA engineers and designers should be involved to identify edge cases, negative scenarios and test coverage. The best criteria integrate perspectives from all disciplines, giving early‑stage teams a shared language for success.

Benefits for early‑stage design and product teams

- Early quality standards: Startups often launch a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) to test hypotheses. Acceptance criteria establish quality thresholds from day one, preventing an MVP from becoming a collection of half‑finished experiments. They also set performance benchmarks – for example, requiring sign‑in to take less than two seconds – that guide engineering effort.

- Anchoring around outcomes: In the 2024 State of Product Management report, a majority of product managers preferred measuring success using outcomes rather than output metrics. Acceptance criteria make this practical by tying features to measurable outcomes like conversion rates, error rates or user satisfaction scores, not just delivery of code.

- Faster onboarding and cross‑functional alignment: New hires can get up to speed quickly when every ticket includes acceptance criteria. They serve as mini requirement documents that summarise context, desired behaviour and constraints. When teams hire consultants or freelancers, acceptance criteria reduce ramp‑up time and ensure consistent quality.

- Defense against scope creep: Dovetail notes that acceptance criteria prevent scope creep. When additional requirements emerge mid‑sprint, teams can refer back to agreed criteria. Anything outside the list becomes a candidate for future sprints, preserving focus.

- Improved stakeholder trust: Customers, investors and leadership can see exactly what a feature will deliver. This transparency is vital when funding is tight and trust must be built quickly.

Best practices & tips

- Keep criteria outcome‑oriented: Focus on the user’s goal and desired results. Avoid prescribing implementation details. Acceptance criteria should not include statements like “use React hooks for state management.” Scrum Alliance warns against telling the team how to achieve the work.

- Include negative scenarios: Consider invalid inputs, errors and edge cases. aqua cloud emphasises clarifying what acceptance criteria is not. Define how the system should behave when a user enters an invalid password, loses connection or lacks permissions.

- Lock criteria by sprint start: Revisit and refine criteria during refinement, but once the sprint starts, only change them in exceptional circumstances. Constant changes undermine predictability and morale.

- Document criteria consistently: Store them in your issue tracker (e.g., Jira), Confluence or your product documentation so they are easily accessible. Use templates or custom fields for consistency. The 2024 product management report notes a trend toward tool consolidation and standardisation; consistent criteria documentation supports this.

- Choose format based on complexity: Use Gherkin for flows with multiple steps and dependencies. Use checklists for simple UI elements. For complex features, combine both. Don’t be afraid to create custom formats if they work better for your team.

- Avoid overly narrow criteria: Leave room for developer creativity. Instead of requiring an exact UI element, specify the functional outcome. For example, write “users can select a date range” rather than “use a calendar widget with a blue border.”

- Use measurable benchmarks: Where possible, tie performance criteria to numbers (e.g., “search results display in under 1 second” or “90% of password resets complete successfully in first attempt”). This ensures objective evaluation and aligns with outcome‑focused product management.

- Embrace iteration and feedback: After each sprint, reflect on whether the criteria were clear and whether any misinterpretations occurred. Use retrospectives to adjust your templates and practices. Scrum Alliance suggests inspecting and adapting the criteria format during retrospectives.

Conclusion

For startup founders and product leaders, acceptance criteria may seem like yet another process step. In reality, they are a powerful tool for aligning cross‑functional teams, improving product quality and preserving precious time and resources.

They define success in clear, testable terms and provide a shared language for product managers, designers, developers, testers and stakeholders. As modern product management increasingly emphasises outcomes over output, acceptance criteria become the anchor for delivering value rather than just delivering code.

Don’t wait until your product is off the rails to adopt this practice. Start writing acceptance criteria for your next user story. Invite your team to refine them together. You’ll be surprised at how much smoother your next launch feels when everyone knows what “done” truly means.

FAQ

Q1: What do you mean by acceptance criteria?

Acceptance criteria are specific, testable conditions a user story or deliverable must satisfy to be considered complete. They define what needs to be built, provide stakeholders with clear expectations and give testers measurable pass/fail conditions.

Q2: What is an example of acceptance criteria?

For the user story “As a website user, I want to recover my password so I can access my account,” acceptance criteria might be:

- Given the user is on the login page, when they click “Forgot Password” and submit a valid email, then the system sends a password recovery link.

- Following the link allows them to set a new password and displays a confirmation message.

A checklist example for a hotel search interface could include: the search input is at the top of the page; the placeholder reads “Where are you going?”; it supports city, hotel name and street; and inputs are limited to 200 characters.

Q3: What are the 4 C’s of acceptance criteria?

While not a universal standard, many teams use the “4 C’s” mnemonic: Clear (easy for everyone to understand), Concise (no unnecessary words), Correct (captures stakeholder expectations), and Testable (supports objective pass/fail evaluation). These traits align with widely recommended qualities.

Q4: What is acceptance criteria vs definition of done?

Acceptance criteria are unique to each user story. They specify how that feature must behave to be accepted – for example, “users can checkout with PayPal, Google Pay and Apple Pay.” The definition of done is a universal checklist applied to all backlog items (e.g., code reviewed, tests passed). aqua cloud clarifies that DoD ensures overall quality and consistency, while acceptance criteria ensure specific functionality meets stakeholder expectations. In practice, you use the DoD and acceptance criteria together: a user story is only complete when both the DoD and its acceptance criteria are satisfied.

.avif)