What Is an Agile Epic? Guide (2026)

Understand what an agile epic is, its role in organizing work, and how to manage epics in your product backlog.

Imagine a small team that tries to deliver a massive feature set all at once. The release drifts, the code becomes hard to maintain, and early users lose interest. Splitting the work into smaller increments tied to clear outcomes would have helped. This piece explains what an agile epic is, why epics matter in product development and project management, and how to use them well. It will touch on product backlogs, user stories, incremental delivery, cross‑team collaboration, and scalable planning.

What is an agile epic and how is it structured?

The agile community describes an epic as a large chunk of work that can be broken down into smaller stories. It spans multiple sprints and the scope is flexible. Productboard defines an epic similarly, emphasising that its stories share a strategic goal and may span multiple projects. ProductPlan says epics sit between themes and stories. In Scrum, an epic is any user story too big for a single sprint; if the work takes weeks rather than days, break it down. If you’ve ever wondered what is an agile epic, think of it as a bridge between a big idea and the smaller tasks that bring it to life.

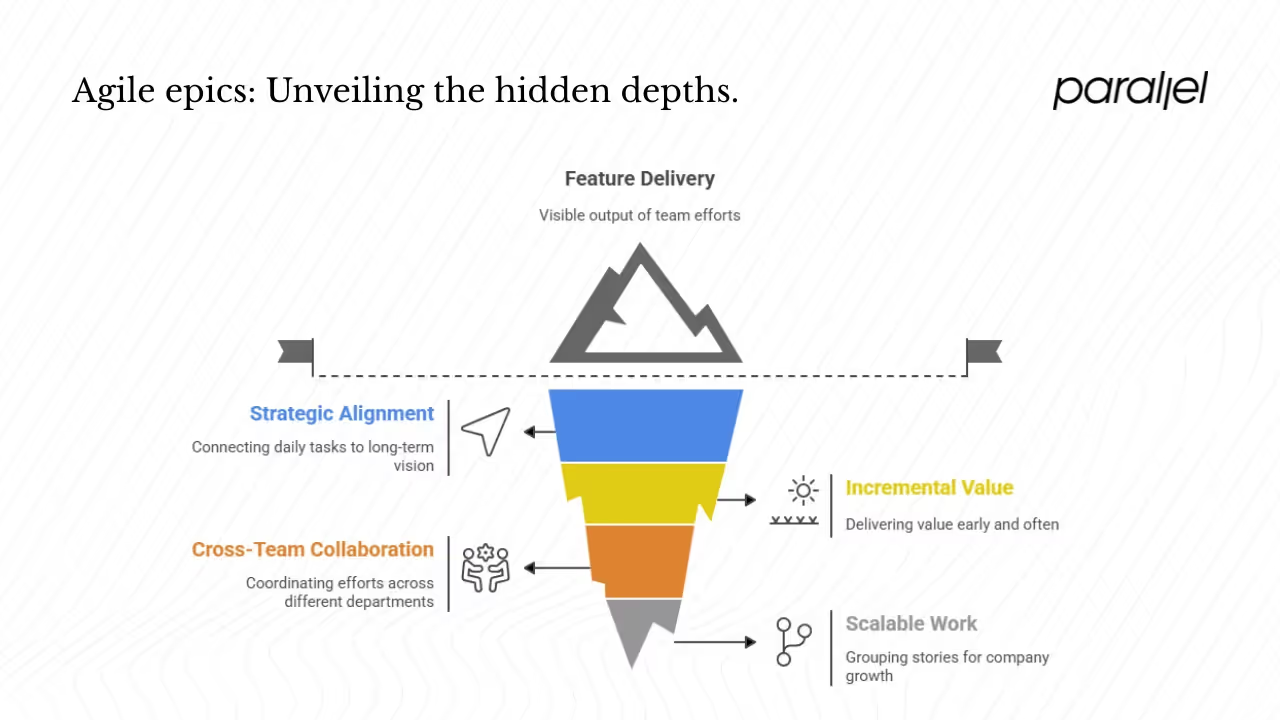

How do epics, themes, and initiatives fit into the hierarchy?

Understanding where epics sit in the hierarchy helps teams link daily tasks to the long‑term vision. A theme is a broad organisational goal that drives the creation of epics and initiatives. A product roadmap is expressed as a set of initiatives plotted over time. Splitting initiatives into epics ensures the team’s daily work remains connected to business goals. Productboard echoes this: themes are long‑term strategic objectives, epics are collections of tasks that break those objectives into shippable units, and user stories are the smallest units of work. This structure gives product and engineering teams a shared language for thinking about size and scope.

Why do epics matter for startups and product teams?

1) Managing large feature sets without losing focus

Early‑stage startups often need to ship big features quickly. Without a structure for splitting work into small deliverables, they end up building monoliths that take months. Epics provide a middle layer between themes and stories. For example, instead of “build onboarding,” define an onboarding epic with child stories for the welcome flow, sign‑up API and welcome email. This illustrates what is an agile epic: a way to slice a big feature into bite‑sized pieces while keeping the larger purpose in sight.

2) Connecting strategy and backlog

Epics link the product backlog to strategic goals. A roadmap explains how a product will change over time; epics on that roadmap ensure daily work remains tied to the long‑term plan. Productboard points out that when several epics share a common objective, they are grouped under a theme. This hierarchy lets leaders look at a backlog and see which big objectives are being advanced.

So what is an agile epic in this context? It’s the container that threads day‑to‑day work back to the product vision.

3) Incremental delivery of value

Delivering value early and often is central to agile. Atlassian emphasises that epics should be broken down so that teams can continue to ship value regularly. Instead of waiting for a complete redesign, a team can release improvements in stages and gather feedback. As the epic progresses through several sprints, scope can change based on user feedback. This incremental delivery reduces risk and keeps users engaged.

4) Coordinating cross‑team collaboration

Large bodies of work often require skills from design, engineering, marketing and operations. Epics provide a way to coordinate this collaboration. The “March 2050 Space Tourism Launch” epic in Atlassian’s example brings together a software team (focused on ticketing) and a propulsion team (focused on fuel and hardware). Productboard’s example of pivoting a travel agency to an experienced marketplace shows epics that span multiple teams—launching a marketplace, onboarding providers, expanding the booking system and building a mobile app. Each epic contains stories assigned to different departments, making it clear how cross‑team efforts contribute to a shared goal.

5) Scaling work as the company grows

As a startup scales, a simple backlog can quickly become chaotic. Epics introduce a way to group related stories and maintain a connection to strategy. They also serve as reporting units that leaders can monitor.

What are the components of a well-crafted epic?

Another way to answer what is an agile epic is to examine its parts.

- A well‑crafted epic isn’t just a label; it connects user stories, strategy and metrics.

- A well‑crafted epic ties to a set of user stories in the backlog; each story should deliver a small increment of value within a single sprint. Stories within an epic share the same strategic goal and often a success metric, such as conversion rate or time‑to‑value.

- Epics are flexible: as teams learn, stories can be added or removed. They should be big enough to span several weeks but small enough to show progress.

- Each epic has an owner—typically a product manager working with engineering and design—who refines the scope and collaborates with stakeholders to deliver the stories.

How to split an epic into user stories and backlog items

Breaking down an epic can feel daunting. When people ask what is an agile epic, they often really mean “how do I break one down?” Atlassian suggests thinking about the people and flows involved: create separate stories for different user personas—for example, a quick login for new visitors versus returning customers.

Map the workflow and write a story for each step. You can also slice by discipline: separate design, technical and content tasks as Productboard does when launching a marketplace. Keep stories small enough to finish in one sprint. Order them based on value, risk and dependency; tackling the riskiest piece first helps de‑risk the rest.

A helpful tip is to create a simple outline with bullet points listing candidate stories. Discuss it with the team, refine, and then add them to the backlog. Keep revisiting the list; as the epic progresses, you may discover new stories or decide some are no longer needed.

How do you split an epic into user stories and backlog items?

1) Epics in Scrum

If you’re wondering what is an agile epic from a process perspective, Scrum provides a clear picture.

In Scrum, work is organized in sprints (time‑boxed iterations) of one to four weeks. User stories are pulled from the product backlog into the sprint backlog. Epics exist outside the sprint; they span multiple sprints and provide context. As sprints complete, teams update the epic with progress and adjust its stories based on learnings. A burndown chart visualises the remaining work in an epic over time. That chart shows whether the epic is on track and makes progress visible.

2) Epics in Kanban and other methods

Kanban teams don’t work in fixed sprints but focus on continuous delivery. Epics can still be useful; they act as containers grouping related cards on a board. Many tools allow epics to be represented as parent tasks that track progress across columns. The idea remains the same: link tasks to a bigger objective, track progress, and adjust scope as needed.

3) Roadmapping and planning

Epics are also planning units on product roadmaps. Productboard points out that epics roll up into themes on a roadmap. This helps leadership see when broad objectives will be addressed. In Jira and other tools, epics can be plotted on timeline views. When planning a quarter, you might allocate a number of sprints to each epic and set milestones for the main metric.

What are the best practices for working with epics?

1) Start Lean

- Begin with a short goal statement rather than a detailed plan

- Define a simple success metric from the start

- Add detail only as you learn more during execution

2) Involve the Right People Early

- Bring engineering into the discussion to validate feasibility

- Include design so user experience is factored into planning

- Make sure all disciplines understand the epic’s purpose and outcome

3) Use Clear Metrics

- Choose one or two measurable indicators, like:

- Conversion rate

- Time-to-value

- Tie the metric directly to the epic’s goal so progress can be tracked

4) Deliver in Increments

- Ship small pieces of value every sprint

- Gather feedback continuously and adjust direction if needed

- Treat the epic as an evolving container, not a rigid plan

5) Review Regularly

- Revisit epics during planning or refinement sessions

- Split large epics into smaller ones when scope grows

- Close the epic when the defined goal is achieved

6) Stay Flexible

- Avoid mapping out every story up front

- Leave space for discovery, adaptation, and learning

What are the common challenges and pitfalls with epics?

1) Being Too Vague or Large

- Epics that lack focus become overwhelming

- Unclear objectives make it difficult for teams to align

2) Different Views of “Done”

- Stakeholders may have conflicting expectations

- Without clear acceptance criteria, teams struggle to close epics

3) Treating Epics as Mini-Projects

- Thinking of them as fixed contracts creates rigidity

- Teams lose the ability to adapt to new insights

4) Tooling and Coordination Issues

- Overcomplicated tools slow teams down

- Lack of shared visibility leads to misalignment

How to Avoid These Pitfalls:

- Define a clear outcome and metric for each epic

- Agree on acceptance criteria early with all stakeholders

- Keep scope flexible to allow adjustments

- Use simple, transparent tooling to track progress

- Assign an owner for accountability and schedule regular touch points

What are some examples and case studies of epics in action?

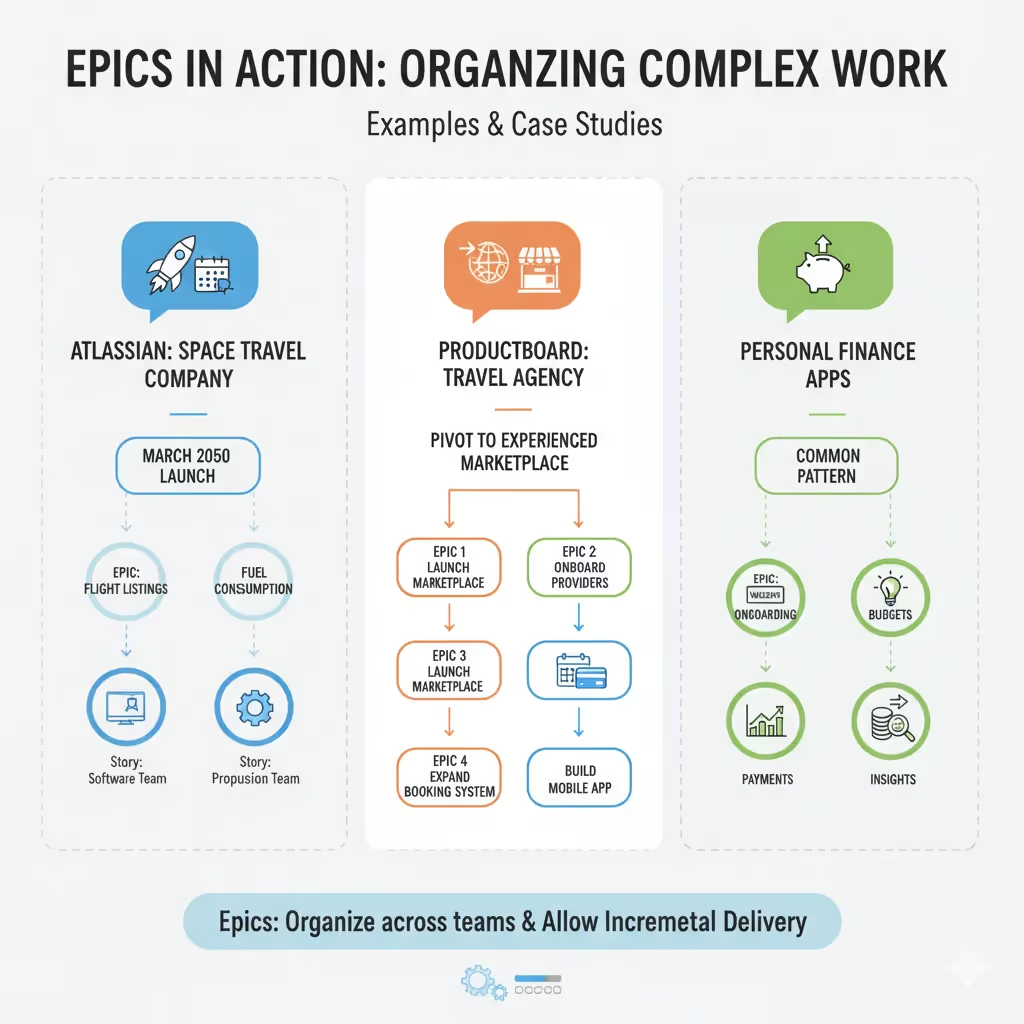

Atlassian illustrates an epic by imagining a space‑travel company planning a March 2050 launch. The epic covers updating flight listings and improving fuel consumption, with software and propulsion teams contributing stories.

Productboard describes a travel agency pivoting to an experienced marketplace; four epics—launching the marketplace, onboarding providers, expanding the booking system and building a mobile app—organise the work.

Another common pattern we see is in personal finance apps, where epics are defined for onboarding, budgets, payments and insights.

These examples illustrate how epics organise complex work across teams and allow incremental delivery.

When should you avoid epics and use simpler alternatives?

Epics add overhead. For very small teams or early MVPs, a simple backlog with stories and themes is often enough. If work is loosely defined, forcing it into an epic creates unnecessary bureaucracy. Alternatives include using themes and stories or grouping work by feature flags; the aim is clarity, not compliance.

Conclusion

Understanding what is an agile epic is less about vocabulary and more about how teams think about scope. An epic represents a goal larger than a single user story but small enough to deliver within a handful of sprints. Used well, epics tie everyday tasks to strategy, enable incremental delivery, and facilitate cross‑team collaboration. They also surface coordination challenges and encourage teams to keep learning and adapting.

For early‑stage startups, epics can be a lifeline: they help avoid the trap of building huge feature sets that never see the light of day. Yet they must remain flexible. Don’t turn epics into rigid projects; keep them lean, let scope change based on feedback, and close them when you meet the metric. Take time to review your current epics. Are they tied to clear goals? Do they still matter? If they feel bloated, split them up. Use epics as a tool for clarity and progress, not as an end in themselves.

Keep asking yourself what is an agile epic and whether each large piece of work really needs one. Doing so will keep your team honest and focused on delivering value overall.

In our experience, this mental check saves time and frustration for your team.

Epics are living tools; they should adapt as your team learns. Stay nimble, and let your process serve the product and its users.

FAQ

1) How long is an epic in Agile?

There is no strict duration. Epics are measured in weeks rather than hours or days and typically span several sprints. Choose a scope that fits your goals and allows for learning and incremental delivery.

2) What is an epic vs. a sprint?

A sprint is a one‑to‑four‑week iteration in Scrum. An epic is a larger body of work that spans multiple sprints.

3) How many sprints are in an epic?

There is no fixed number of sprints in an epic. Size depends on complexity and team capacity. Track progress with burndown charts and adjust scope if it drags on.

4) What are epics with an example?

Examples include Atlassian’s space‑tourism launch and Productboard’s marketplace pivot, both of which organise multiple teams and sprints around clear goals.

.avif)