What Are Jobs to Be Done? Guide (2026)

Discover the Jobs to Be Done framework, which focuses on understanding the tasks users hire products to accomplish.

When founders ask me what jobs are to be done, I explain that it’s not about features, it’s about progress. People don’t buy your product because of its characteristics; they hire it to accomplish a goal. Once you realise that, your product becomes one option among many ways to get the job done. That shift has helped our early‑stage clients stop chasing shiny objects and focus on the outcome their audience cares about. In this article I’ll answer the question directly, show how to define and research jobs, and share examples, pitfalls and advanced ideas drawn from my work at Parallel.

What is Jobs‑to‑Be‑Done?

Jobs‑to‑Be‑Done (JTBD) is a way of looking at customer behaviour that focuses on what people hope to achieve. Instead of asking “Who is my customer?” we ask, “What progress is my customer hiring us to make?” According to Product School’s 2024 guide, JTBD reframes a market around the job someone is trying to get done. A “job” is not a feature; it’s the underlying goal, such as “get somewhere faster” rather than “own a faster horse.” Nielsen Norman Group notes that JTBD captures functional and emotional success criteria, shifting the focus away from tasks within an interface and toward the outcome a person desires.

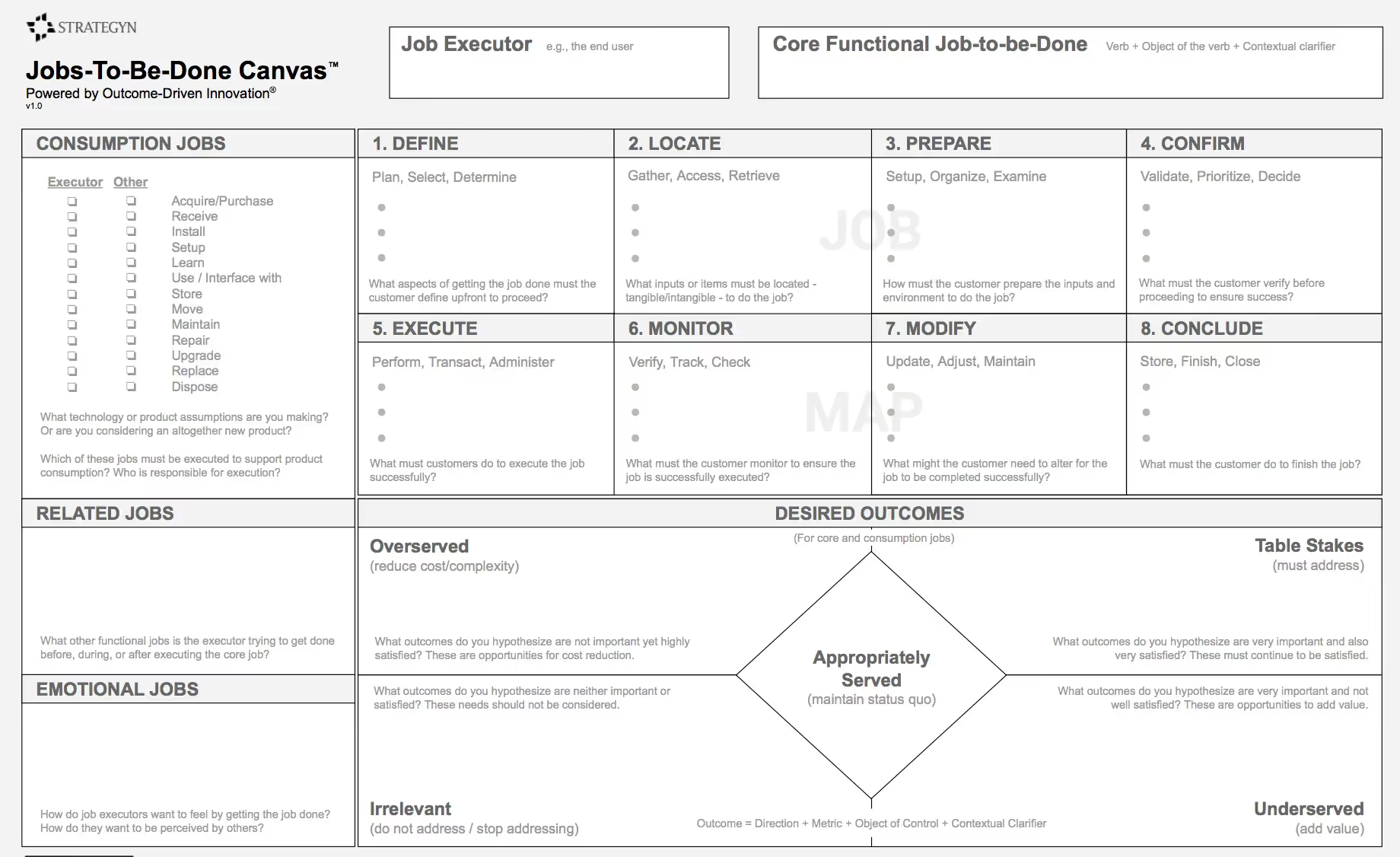

The idea comes from innovation research. Clayton Christensen used the metaphor of “hiring” products to explain why some offerings succeed. Later practitioners developed processes like Outcome‑Driven Innovation to document desired outcomes and reveal unmet needs. Thinking this way broadens your view.

JTBD matters because it helps teams avoid feature creep and build what users need. In my experience working with early‑stage machine learning and SaaS teams, I’ve seen that asking what jobs to be done keeps priorities in sync with the customer’s progress. The 2024 State of Product Management report found that most product managers measure success using outcomes such as revenue, retention and usage. This outcome focus reflects a wider shift toward connecting roadmaps to actual jobs. ProductPlan’s survey also showed that 76% of teams view product strategy as a critical function and 58% want roadmapping handled together with strategy. A job's lens clarifies which outcomes matter and helps you choose the right investments.

Anatomy of a job

A job is more than a task; it has functional, emotional and social layers. Understanding these layers helps answer what jobs to be done with greater depth.

- Functional – The practical task, such as sending a parcel or booking a flight. The Uxtweak guide explains that functional jobs involve specific actions and practical problems.

- Emotional – People hire products to feel a certain way, such as confidence or security.

- Social – People also consider how they are perceived. Choosing an eco‑friendly brand may signal care for the environment.

Some researchers also mention a transformational dimension: a job that changes a person’s identity. For example, learning a language helps someone shift from tourist to citizen. In practice I view this as an aspiration that connects multiple jobs over time. Most products need only address the functional, emotional and social layers, but being aware of transformational jobs can reveal deeper motivations.

Crafting a job statement

Defining a job clearly is crucial. When people ask what jobs are to be done in practical terms, the answer starts with a well‑crafted job statement. A good statement distils your research into a sentence that captures context, action and outcome. The structure often looks like this:

When [context], I want to [action/job], so I can [desired outcome].

Here are two examples:

- When I’m commuting on a crowded train, I want to listen to a podcast so I can pass the time and arrive in a better mood.

- When I land in a new city, I want to quickly get to my hotel so I can feel safe and start my trip without stress.

Notice that these statements avoid mentioning your product; they describe progress in the real world. When crafting your own, capture the context (when), the action (what) and the outcome (why) in a single sentence. Keep it solution‑agnostic and validate with users to ensure it reflects their motivation and will stay relevant even as technology changes.

Discovering jobs

To answer what jobs are to be done in practice, you need research. Based on our projects at Parallel, I suggest a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods:

- Customer interviews – Talk to users about moments when they chose your product or an alternative. Start with broad questions and then work backward from decisions to triggers.

- Contextual inquiry – Observe people in their environment to see struggles you might never hear in an interview.

- Diary studies, surveys and job mapping – Ask participants to log tasks and feelings, quantify how important and satisfied they are with outcomes and sketch the steps of their job. Together these methods surface patterns and reveal friction points.

Prioritisation matters. Focus on jobs that are important yet underserved and consider whether your organisation can deliver. A jobs lens simplifies strategy by clarifying which jobs to tackle first and makes it easier to measure progress. Start with one or two jobs and expand only after you’ve delivered meaningful outcomes.

From jobs to product strategy

Once you understand the job, translate it into product use cases and metrics. For teams grappling with what are jobs to be done, this is where the concept becomes actionable:

- Map jobs to flows and metrics – Outline how users progress through your product and link each job to metrics. For example, for “stay motivated to work out,” you might track weekly sessions or streak length.

- Plan the roadmap – Prioritise features that materially improve the job outcome. ProductPlan’s survey found that most teams expect their tools to support product strategy and roadmapping together. Use jobs to anchor both.

Avoid building redundant features that solve the same job. Revisit your job list regularly because contexts change and new jobs appear.

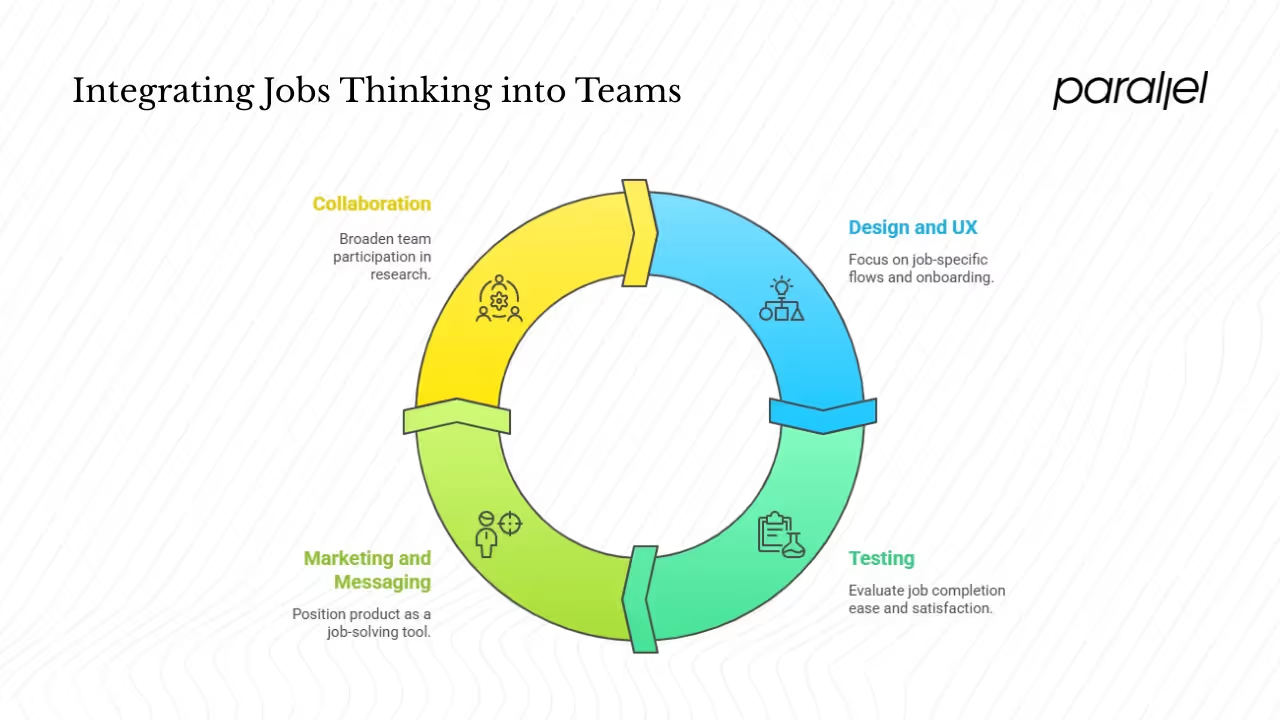

Integrating jobs thinking into teams

A shared language around jobs helps design, engineering and marketing move together. Sharing this understanding answers what are jobs to be done across the organisation. Here’s how we apply it:

- Design and UX – During brainstorming and reviews, reference job statements. Ask: which job does this work help with? Prioritise flows that remove friction from the job. When building onboarding, focus on the job “get started quickly” rather than adding more prompts.

- Testing – Evaluate whether users can complete the job easily. Run experiments that measure job‑specific metrics such as time to completion or emotional satisfaction. A/B testing is more meaningful when framed around jobs instead of clicks.

- Marketing and messaging – Speak to the progress people want to make. Instead of listing features, position your product as a tool that helps users achieve their job (“Dinner on the table in 30 minutes”). Segment users by the jobs they hire your product for rather than demographics.

- Collaboration – Bring multiple roles into research. The ProductPlan report notes that 73% of product managers participate in research, but only 45% of designers and 23% of technical leads do. Broadening participation increases shared understanding and reduces misalignment.

Examples and pitfalls

Nothing illustrates JTBD like real stories. The classic milkshake example shows this thinking: a fast‑food chain discovered that commuters hired milkshakes to make long drives engaging and keep them full, so they thickened the drink and added bits of fruit.

Modern companies follow the same pattern. Zoom helps remote teams feel together, Duolingo makes language practice bite‑sized, Uber moves you without a car, and Spotify feeds your hunger for music. Each started with a clear job and later expanded.

Common pitfalls include:

- Overlooking context – Focusing only on the functional task or confusing steps with jobs ignores emotional and social context. LogRocket warns that over‑indexing on functional jobs misses the full picture.

- Weak or biased statements – Vague wording or folding solutions into the job description makes it hard to innovate. A job statement should be clear, grounded in context and outcome, and avoid assuming a particular feature.

- Taking on too much – Trying to serve unrelated jobs or skipping validation dilutes focus. Start with the core job, talk to users and iterate. The ProductPlan report notes that gathering feedback is one of the hardest activities, so make it a priority.

Advanced topics and emerging ideas

As your understanding matures, you can layer more advanced methods on top of JTBD — deepening your grasp of what are jobs to be done and how contexts change:

- Job hierarchies – Distinguish between core, related and supporting jobs. For a budgeting app, the core job might be “manage my money,” while tracking expenses or filing taxes are related jobs. Mapping these relationships prevents you from misclassifying supporting tasks as core needs.

- New jobs and broader competition – Market shifts create new jobs and new competitors. Remote work tools exposed needs for virtual collaboration, and anything a customer hires to achieve the same progress counts as competition.

- Quantitative and combined approaches – Use surveys to rate the importance of outcomes versus satisfaction and cluster users by job needs. Pair jobs with personas or opportunity trees to visualise connections and prioritise work.

Conclusion

Asking what jobs to be done reframes product work. It shifts the conversation from “What should we build?” to “What progress do people hire us to help them make?” This perspective encourages deeper research, surfaces emotional and social needs and provides a clear north star for strategy. For early‑stage teams, a job lens reduces waste and focuses resources on the outcomes that matter. Start by identifying one or two jobs, write clear statements, validate them with users and measure whether your product helps people succeed. Use the framework as a guide rather than a rigid process. With practice, you’ll see that people hire your product not for its own sake but for the progress it enables.

FAQ

1) What are examples of jobs to be done?

Jobs are everywhere in daily life. A few examples:

- Commuting – On a commute I might hire a podcast or a playlist to pass the time so I don’t feel bored.

- Traveling and remote work – When I’m far from home, I want to find my way around unfamiliar places or collaborate with my team easily. Google Maps, ride‑hailing services, Zoom and Slack all compete for this job by providing directions, rides or communication.

- Learning a language – When I try to learn a new tongue, I want to retain words efficiently. Duolingo structures lessons into small challenges and uses gamification to keep learners motivated.

These examples show that one job can be served by many products; your product competes with any alternative that accomplishes the same progress.

2) What is the meaning of jobs to be done?

JTBD focuses on the progress a customer wants to make rather than the product itself. A job is the underlying goal someone hires a product to accomplish. This perspective shifts attention from feature lists and demographics to motivation and context.

3) What is the main job of the JTBD?

The main job is the core progress a user wants to make in a given context. For a flight it’s “get me to my destination.” Secondary jobs such as comfort or price can differentiate you later but shouldn’t distract you from serving the primary outcome.

4) What are the types of jobs in JTBD?

Jobs fall into three primary categories: functional (practical tasks), emotional (feelings of confidence or security) and social (how users want to be perceived). Some authors add a transformational dimension, capturing identity shifts such as becoming fluent in a new language. Considering all these dimensions ensures you address the full spectrum of motivation.

.avif)