What Are Mental Models? Guide (2026)

Learn about mental models, how they influence user behavior, and how designers leverage them to create intuitive interfaces.

When you run a young product company, there’s rarely perfect data. As you juggle growth, design and team‑building, you’re constantly forced to choose on incomplete information. That’s where mental models come in. They’re compact explanations of how things work. Understanding what are mental models helps you make sharper calls when there’s no obvious answer. This article explains what mental models are, why they matter for founders, product managers and design leaders, and how to build and apply them. I’ve blended theory with my experience working with early‑stage technology teams to share practical frameworks and answer common questions.

What are mental models?

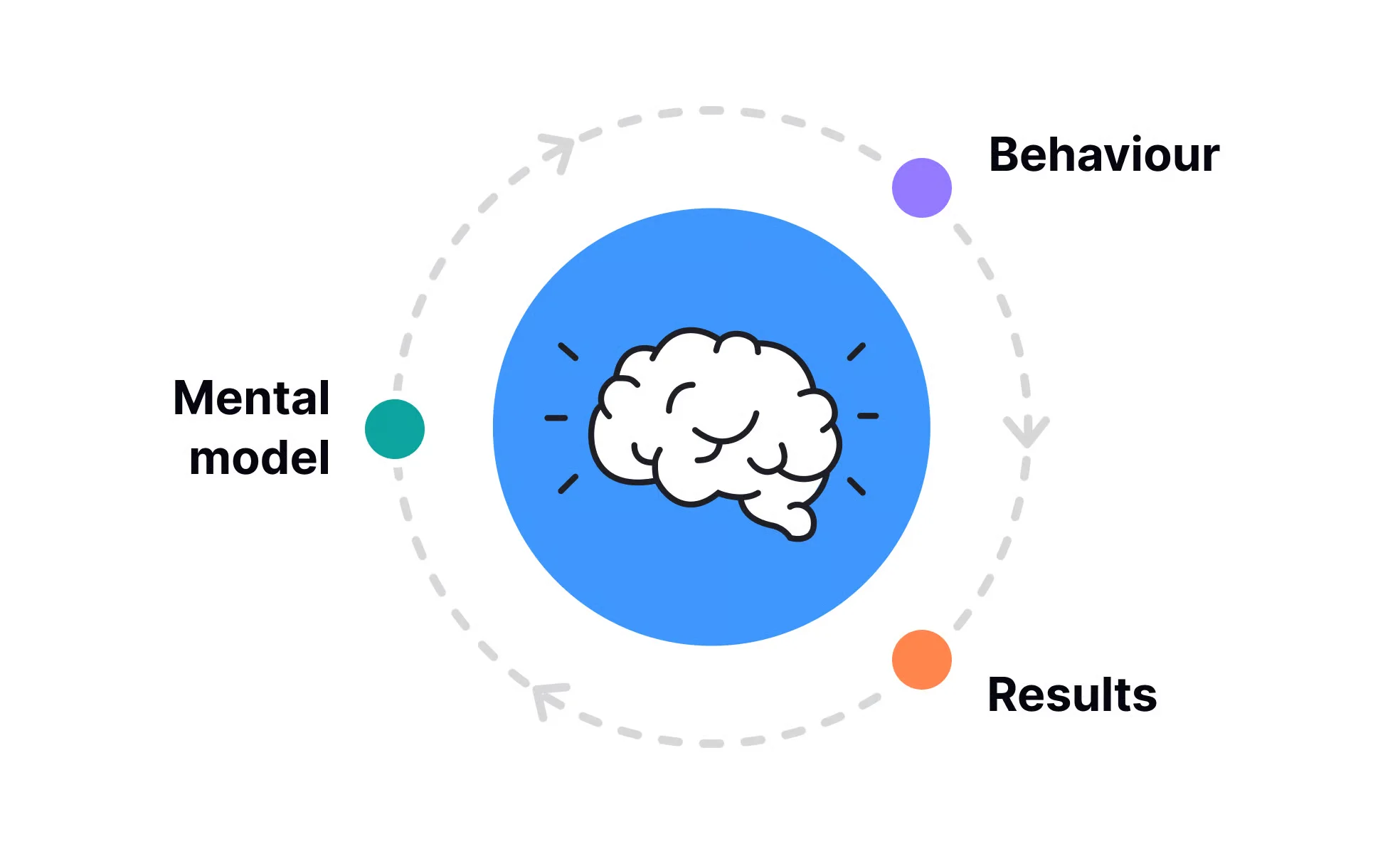

A mental model is a simplified explanation in your mind of how something works. It’s the internal map you use to interpret a situation, anticipate outcomes and decide what to do. Shane Parrish of Farnam Street captures it well when he writes that a mental model is “a simplified explanation of how something works” and likens it to a map that highlights key information while ignoring irrelevant details. James Clear puts it even more plainly: a mental model is “an explanation of how something works” and a “thinking tool” that guides perception and behaviour. These internal maps help us compress complexity into manageable chunks, offering shortcuts that are more deliberate than gut reactions.

Where the idea comes from

The notion has roots in cognitive science. Philip Johnson‑Laird’s mental model theory holds that people build internal representations of external reality to reason and make decisions. According to this theory, reasoners represent only what they believe to be true to reduce the load on working memory. In other words, we simulate reality in our heads using simplified scenarios. Later, thinkers like Charlie Munger popularised the idea for business strategy. Munger advocates building a “latticework” of mental models across disciplines, a view echoed by Clear’s observation that a handful of versatile mental models carry heavy freight for effective thinking.

Why startup and product leaders should care

In a startup you move fast, but you often deal with ambiguity. When you design a feature, pick a market segment or structure a team, you rely on assumptions about how users behave and systems interact. Mental models make these assumptions explicit so you can test and refine them. They help you spot patterns instead of being driven by noise. For example, understanding supply and demand helps you price a feature; recognising network effects helps you prioritise referral loops over more features; awareness of the availability heuristic warns you that recent user feedback may loom too large. As a designer, aligning your interface with the user’s mental model—how they believe a system works—reduces confusion. As a product manager, a portfolio of mental models gives you the vocabulary to discuss trade‑offs with peers, avoid biased decisions and communicate better with engineers and researchers.

What makes a good mental model?

Not all mental models are equal. The best ones share certain traits:

- Usefulness over accuracy – A model is a simplification; it will omit details. The test is whether it helps you reason better, not whether it matches reality perfectly. Clear stresses that mental models are imperfect but useful.

- Breadth – Valuable models apply across contexts. “Supply and demand” illuminates pricing but also resource allocation. “Second‑order thinking” helps in product roadmaps and hiring decisions. Munger argues that a small set of powerful models can explain much of the world.

- Flexibility – Models should evolve with new evidence. Holding onto a single model risks blind spots. Better to build a lattice of models and update them when data contradict them.

- Perception filters – Models shape what you notice and what you ignore. Being aware of your models allows you to adjust your focus deliberately rather than unconsciously.

- Structured shortcuts and learning scaffolds – Models reduce cognitive load and provide scaffolds that make it easier to integrate new information.

Categories of mental models for founders, product managers and designers

There are many types of models, but a handful matter most for product work. Systems and feedback models reveal loops, network effects and compounding growth. Economic models such as supply and demand and opportunity cost help you price features and allocate resources. Behavioural models draw attention to cognitive shortcuts like the availability heuristic and loss aversion. Problem‑solving patterns—first principles, inversion and second‑order thinking—prompt you to question assumptions and anticipate consequences. Finally, perception models remind you to match your design’s conceptual model to the user’s mental model. Knowing what are mental models in these categories helps you choose the right lens for each decision while avoiding untested assumptions.

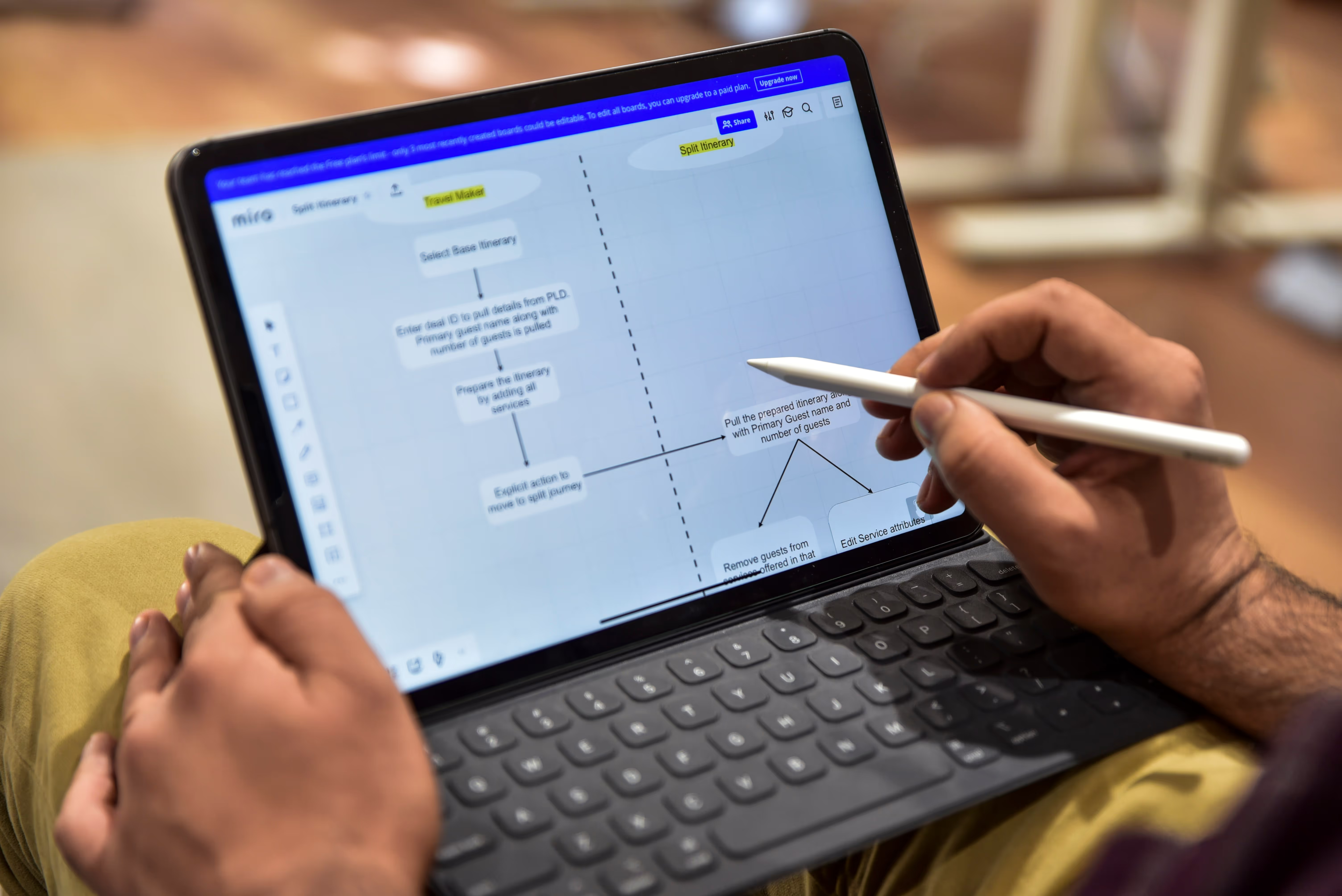

Building and applying mental models

Understanding what are mental models is only useful if you apply them. Start by writing down the assumptions you already lean on so you can test them. Read across disciplines to add new models to your toolkit, and map each one to a real problem—for instance, use opportunity cost to weigh feature requests or inversion to stress‑test a launch plan. Combine several models rather than clinging to a single one, and revisit them as you learn. During planning or retrospectives, ask, “Which mental model are we using?” to bring hidden assumptions to light. Beware of treating one model as gospel; context changes, so update your thinking and always recall that the map is not the territory.

Startup and design use‑cases

Mental models shine when you’re searching for product‑market fit, prioritising features, scaling your team and shaping the user experience. Inversion and feedback loops help you identify what might prevent fit and highlight that retention drives growth. Opportunity cost and diminishing returns keep prioritisation grounded in value rather than volume; the ProductPlan survey shows that 42% of product professionals balance discovery and delivery while 39% spend more time on delivery. Systems models inform decision‑making structures as companies grow—ProductPlan notes that CEOs control prioritisation in 43% of small firms but product leaders gain influence as firms scale. Finally, matching the conceptual model of your design to the user’s mental model reduces friction; Maze’s research links integrated user research with higher usability and satisfaction. Knowing what mental models are in these contexts helps you focus on what matters.

Recent research underscores how mental models and user insight combine to deliver better products. Maze’s 2025 report found that embedding user research in product decisions improved usability by 83%, increased customer satisfaction by 63% and accelerated product‑market fit and retention. The same report notes that 55 percent of product leaders expect demand for research to rise and that 58 percent already use AI tools to analyse feedback. The 2024 State of Product Management survey reveals a mismatch: while 73 percent of product managers conduct user research, only 14 percent of organisations involve a cross‑functional product trio—PM, designer and engineer—in research sessions. These figures suggest that explicit models help teams interpret research. They enable teams to work together more easily.

I’ve seen early‑stage AI teams overcomplicate onboarding because they believed users wanted endless customisation. After we switched to a model focused on time to value, we simplified the flow and cut onboarding by 30 percent. This highlights how explicit models guide decisions and shape culture.

Ten essential mental models for product leaders

Here are ten models I lean on often, with brief definitions and tips:

Cultivating a mental‑model mindset

Learning about mental models is an ongoing process, but there are habits that make it easier. Keep a log of the models you use and revisit them after projects: were they helpful? During planning, ask, “what model am I using right now?” and invite colleagues to share theirs. Encourage reading across domains; the best insights often come from outside your field. Build a shared vocabulary in your team. When we adopted a practice of naming the model we were using, meetings became shorter because everyone knew the frame of reference. Scenario workshops—where you deliberately apply a model like inversion to a plan—surface blind spots early.

Conclusion

Mental models are not arcane theory; they are everyday tools for clearer thought. Understanding what are mental models gives founders, product managers and design leaders a way to turn chaos into structure. By consciously building a broad toolkit, mapping models to real problems and weaving them into team routines, you gain clarity without chasing fads. The payoff shows up in better product‑market fit, smarter prioritisation and more cohesive organisations. Start with a few models from this article, apply them to your next decision and see how they change your perspective. Then keep adding, adapting and teaching them—the most powerful models are the ones you share.

Over time, your judgement becomes sharper and your team in sync. Keep practising.

FAQ

Q1. What are the 21 mental models?

The question of what are mental models often leads to numbered lists. There is no definitive set; different authors compile different favourites. James Clear lists around two dozen high‑leverage models ranging from supply and demand to loss aversion. Farnam Street’s “Great Mental Models” project covers about one hundred models across disciplines. The exact number matters less than having a varied toolkit.

Q2. What is an example of a mental model in everyday life?

Supply and demand is a classic mental model: when something is scarce and many people want it, the price tends to go up. Inversion is another: when faced with a goal, consider what would prevent it; for example, to stay healthy, think about habits that could make you unwell and avoid them. These examples show what mental models are in practice.

Q3. What best describes mental models?

Mental models are internal frameworks or filters you use to understand how things work and to make decisions. They are simplified representations of reality—maps rather than territories. They shape perception and behaviour, and their usefulness comes from helping you see patterns and avoid mistakes.

Q4. What does it mean to build mental models?

Once you understand what mental models are, building them means deliberately acquiring and refining thinking tools, integrating them into your reasoning and updating them with new evidence. It involves reading across domains, practicing models on real problems and reflecting on their effectiveness. Over time, you build a latticework that helps you navigate complexity without relying solely on instinct.

.avif)