What Is Concept Testing in Marketing? Complete Guide (2026)

Learn about concept testing in marketing, its purpose, methods, and how it helps validate ideas before full‑scale product development.

New products fail at staggering rates. Harvard’s Clayton Christensen estimates that about 30,000 consumer products launch each year and many never catch on. I’ve seen this first‑hand helping early‑stage technology and SaaS teams at Parallel: founders skip listening and end up pivoting.

If you’re wondering what is concept testing in marketing, it’s simply exposing an idea to the people you hope will buy it and asking if it solves a real problem. This guide explains why that matters, shows you how to run a test, and shares stories—from Yamaha and Lego—to illustrate why skipping feedback is risky.

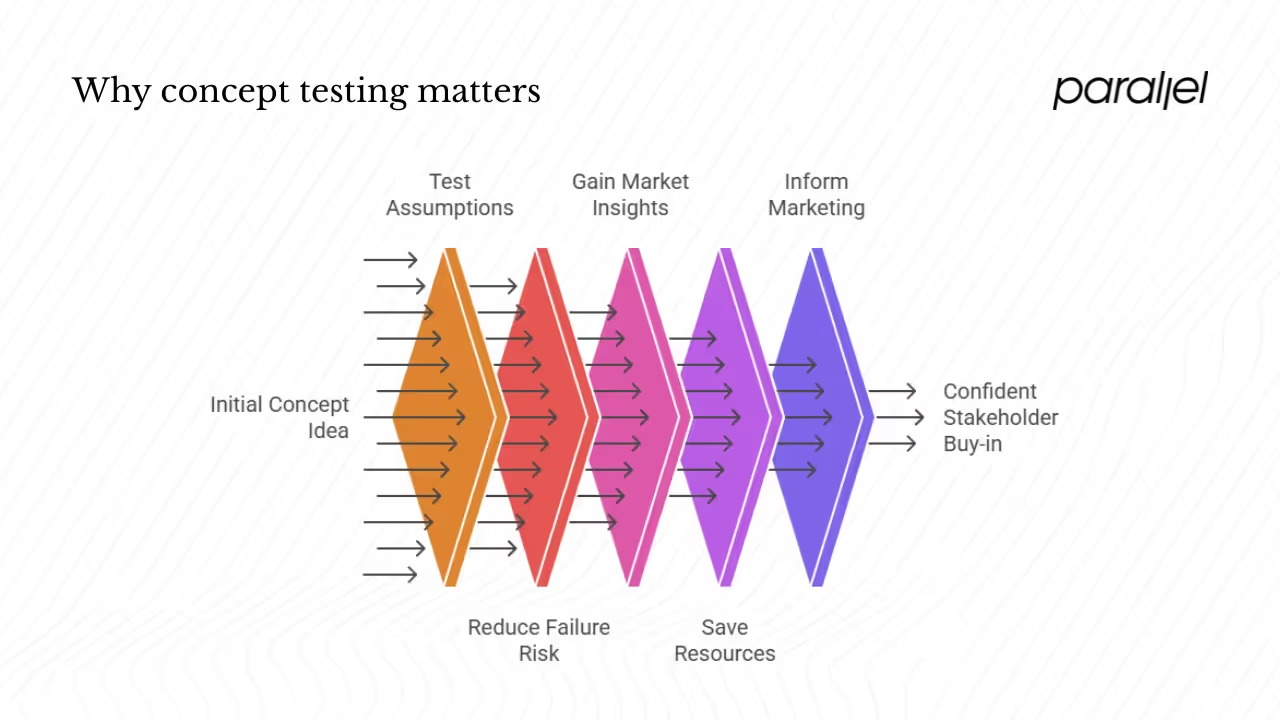

Why concept testing matters

People often ask me, what is concept testing in marketing and why should I care? Concept testing isn’t a fancy term for post‑launch surveys or usability lab sessions; it’s a simple way of asking the market to tell you whether your idea is worth investing in. Dovetail calls it a research method to test assumptions about your target market’s needs and their willingness to buy. Voxco describes concept testing as a method where a target audience is asked to rate their interest, acceptance and willingness to engage with a concept, and those responses guide go‑to‑market decisions. In other words, it’s not about finessing the user interface; it’s about validating whether the problem you think you’re solving actually matters.

Several reasons make this practice critical:

- Reducing failure risk: Nearly 95% of new startup platforms flop. Dovetail points out that concept testing uses a controlled portion of your budget and prevents you from launching something nobody wants. Attest echoes this: investing in product development without testing first is like driving blindfolded, and gathering data ahead of time significantly reduces the chance of a launch nobody wants.

- Gaining insight further than your bubble: The best product teams realise their perspective is limited. Concept testing puts you in direct conversation with the people you hope to serve. It uncovers what features matter most, what messages land and what price points feel fair. These insights go further than internal brainstorming or market reports.

- Saving time and resources: Early validation saves money down the road. Attest points out that while concept testing costs something, in the end it saves time and resources because you address issues when they’re still inexpensive to fix. Vase reminds us that the money spent on testing is negligible compared to the cost of launching a product that fails.

- Informing positioning and marketing: Concept testing isn’t only for product teams; marketers use it to refine messaging. By understanding which parts of your concept appeal most to consumers, you can shape your campaigns.

- Building confidence with stakeholders: Decisions backed by customer evidence are easier to defend. Investors and executives respond better to data than to gut feeling. Attest points out that real data helps secure buy‑in from stakeholders.

Early concept testing means you’re listening before you build. That simple act of humility can save you from the fate of New Coke—a product that failed not because of taste but because Coca‑Cola ignored emotional and nostalgic attachments.

From ideas to evidence: what concept testing looks like

If you’re still wondering what is concept testing in marketing, think of it as an early‑stage market research technique used to evaluate the appeal of an idea, product, service or campaign by gathering feedback from the target audience. Dovetail adds that it involves interviewing users about their acceptance and willingness to buy. Voxco points out that respondents are asked about their interest, acceptance and willingness to engage. The output is evidence on desirability, purchase intent and perceived value—not polished creative assets.

Here are the core components you need to get right:

Clear definition of the concept

People can’t react to a vague idea. Define the problem your concept addresses and describe the main features, benefits and differentiators. Include simple visuals if relevant. The Looppanel guide advises that you should provide clear context but avoid persuasive language. Your goal is to help respondents understand the idea without biasing them.

Measures to collect

A good concept test gathers both quantitative and qualitative data. Common metrics include:

- Overall interest or desirability: Ask respondents how appealing they find the idea on a numeric scale.

- Likelihood to purchase or use: What percentage of your audience would pay for it? Vase’s framework suggests asking: “How likely are you to switch from your current product to this one?”.

- Perceived value and uniqueness: Does the concept feel different from existing options? Does it seem worth the price?

- Brand fit: Does the idea fit with your brand values?

- Usage context: Who will use it, and in what situations? Looppanel encourages asking about purchase preferences and use cases.

Audience definition

Concept testing only works when you’re talking to the right people. Define inclusion and exclusion criteria based on demographics, psychographics and behaviours. Looppanel stresses screening participants to ensure they match your target audience. Vase shows how segmenting by race, lifestyle and shopping habits can uncover nuanced differences.

Price sensitivity

Pricing questions uncover whether people would actually pay for your idea. Ask about willingness to pay at different price points and investigate trade‑offs between price and features. This helps you see the elasticity of demand before you hire engineers.

Comparisons with existing solutions

Show respondents how your concept stacks up against current offerings. Ask which they prefer and why. This reveals how differentiated your idea truly is and whether it solves an unmet need or simply replicates existing features.

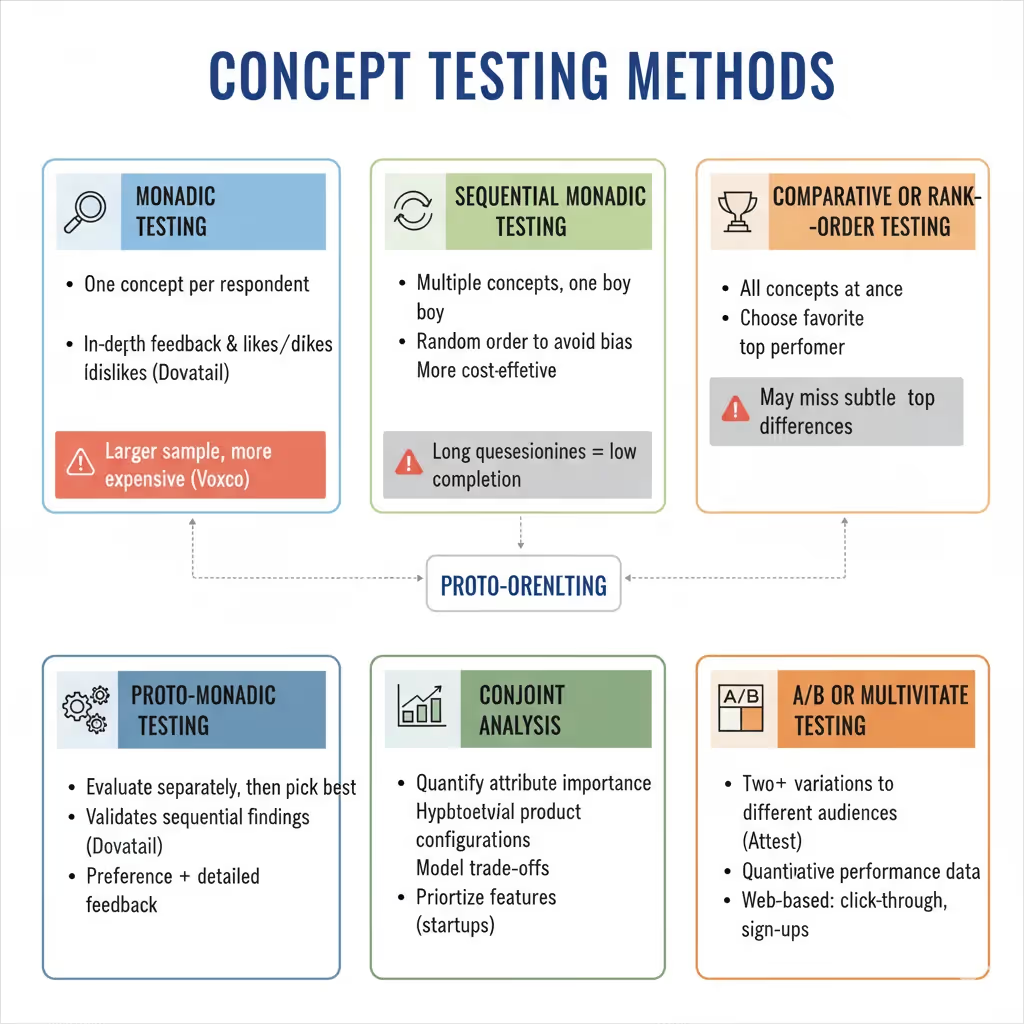

Methods for concept testing

Understanding what is concept testing in marketing will help you choose the right research method. Different designs offer different trade‑offs in cost, depth and sample size. Here are common approaches:

- Monadic testing: Each respondent evaluates only one concept. Dovetail points out that this approach allows in‑depth follow‑up questions and detailed understanding of what people like and would change. Voxco adds that monadic tests require larger sample sizes and can be more expensive.

- Sequential monadic testing: Respondents evaluate multiple concepts one after another. Dovetail explains that concepts should be shown in random order to avoid bias, and this method is more cost‑effective than pure monadic testing. However, long questionnaires may reduce completion rates.

- Comparative or rank‑order testing: Participants see all concepts at once and choose their favourite. This approach quickly identifies the top performer but may miss subtle differences.

- Proto‑monadic testing: A hybrid where respondents first evaluate each concept separately and then pick the best one. Dovetail points out that this combination validates the sequential findings and gives both preference data and detailed feedback.

- Conjoint analysis: When there are many features or price points to test, conjoint analysis helps you quantify which attributes drive purchase decisions. By presenting respondents with hypothetical product configurations, you can model the trade‑offs people make. For early‑stage startups with a complex value proposition, conjoint studies can reveal which features to prioritize or drop.

- A/B or multivariate testing: Attest points out that showing two variations to different audiences can provide quantitative performance data. This is useful for web‑based concepts where you can measure click‑through rates or sign‑ups rather than relying on self‑reported intent.

The choice of method depends on budget, number of concepts, and the depth of insight you need. Small teams often start with comparative testing for quick direction and then dive into monadic tests once they narrow down options.

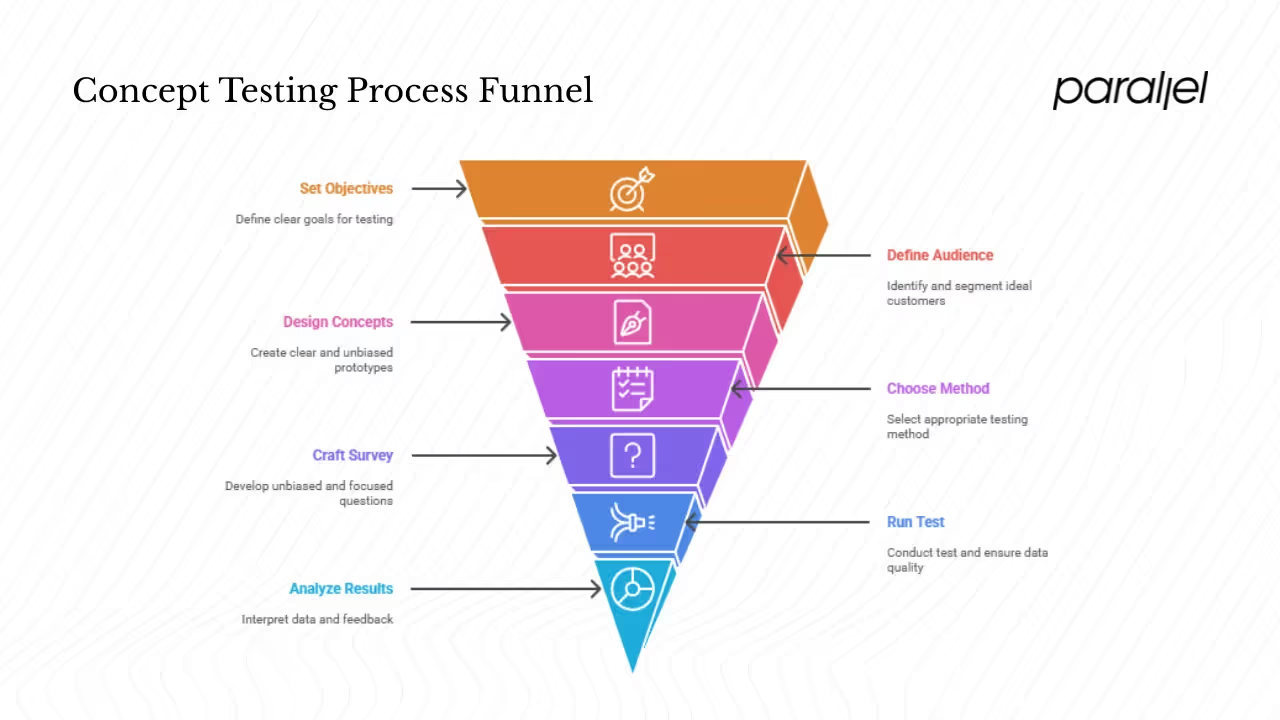

Running a concept test: a step‑by‑step approach

A lot of people think they know what is concept testing in marketing, but the details matter. Here’s a practical process I use with founders and product managers. I’ve blended insights from Dovetail, Attest and Vase with lessons from our own client work.

1. Set clear objectives

Before drafting a survey or building a prototype, articulate what you want to learn. Are you evaluating whether the idea solves a real problem? Are you comparing several possible value propositions? Do you need to understand which features to prioritise? Vase emphasises breaking overall goals into smaller, measurable objectives. For example, rather than asking “Do people like my fitness app?”, you could set the goal “At least 60 % of target users must feel the features justify a subscription fee”.

2. Define and recruit the right audience

Identify your ideal customers and segment by relevant factors: demographics, behaviour, and attitudes. If you’re making a B2B product, talk to decision‑makers. If you’re building a toy, talk to parents and children. Use screening questions to filter out those who don’t fit. Looppanel suggests screening questions to ensure respondents come from the right demographic and segmentation data to refine marketing later. Vase shares an example of a skincare brand that segmented by race, lifestyle and shopping habits to find meaningful patterns.

3. Design your concepts

Prepare descriptions, visuals and prototypes that communicate the idea clearly. Keep each concept at the same degree of fidelity to avoid bias. If you’re testing features or pricing, create variations accordingly. Make sure the concept addresses the same need or job to be done so that comparisons are meaningful.

4. Choose your testing method

Select the method that aligns with your objectives, number of concepts and resources. For early exploration, a comparative test may suffice. For deeper learning about one concept, a monadic or sequential monadic test is better. Conjoint is appropriate when you need to prioritise among many features or price points. Attest summarises the pros and cons of each method, noting that monadic tests provide in‑depth feedback but require larger sample sizes, while sequential monadic tests are more cost‑effective but risk order bias.

5. Craft the survey or interview guide

Create questions that are unbiased and straightforward. Use a mix of quantitative scales and open‑ended prompts. Vase suggests pairing quantitative questions—like asking respondents to rate appeal or likelihood to purchase on a scale—with qualitative questions that probe what they like or dislike and why. Use Likert scales to make analysis easier. Group related questions together to help participants stay focused. Ask about use cases, value perception, uniqueness, and price. If testing multiple concepts, randomise their order to reduce bias.

6. Run the test and ensure data quality

Launch the survey through your chosen platform (SurveyMonkey, Attest, Vase or your own tool). Pay attention to the length; sequential monadic tests can become long and cause fatigue. Use attention checks and data cleaning to remove low‑quality responses. Monitor early results to ensure the sample stays representative of your target segments.

7. Analyze and interpret results

Look at both the numbers and the stories. Vase advises paying attention to open‑ended responses, which often reveal issues you didn’t think to ask about. Segment the data to see whether certain demographics respond differently. Identify which concept scores highest on appeal, purchase intent, and uniqueness. If none meet your success threshold, consider pivoting or iterating. Even negative feedback is valuable; a low score from your ideal users might reveal an unmet need you haven’t addressed.

8. Act on the insights

Use the findings to decide whether to proceed, refine or discard a concept. If one concept clearly wins, move it forward and iterate on the weaker points. If feedback suggests the price is too high, adjust and retest. Share the evidence with stakeholders to get the team on the same page and justify next steps. Concept testing isn’t a one‑off event; repeat it as you refine the product.

Lessons from the field: success stories and pitfalls

Lego: designing for girls

For years, Lego struggled to appeal to young girls. Concept testing revealed that girls preferred building full environments and paying attention to interior detail, unlike boys who were happier with a finished exterior. Using this insight, Lego developed Lego Friends—sets designed with narratives and rich interior spaces. The line became a commercial success and expanded the brand’s audience. The takeaway: don’t assume you know your non‑core market. Let real users tell you what they want.

Yamaha: knobs or sliders?

When Yamaha designed its Montage keyboard, the team wasn’t sure whether users would prefer rotary knobs or sliding faders. Concept testing gave them accurate data and led to the choice of sliders. Without research, the decision could have been arbitrary and alienated professional musicians. A simple preference study saved them from making a costly mistake.

Tesla: gauging purchase intent before building

Tesla famously announced the Model 3 in 2016 before the car existed. They allowed people to place $1,000 deposits, and around 400,000 individuals did so. This type of purchase intent testing gave Tesla confidence that there was real demand and generated cash to fund development. While this method isn’t available to everyone, it shows the power of asking for a commitment early.

New Coke: testing the wrong thing

In the 1980s, Coca‑Cola introduced “New Coke” after taste tests suggested consumers preferred the sweeter formula. The tests ignored the emotional connection consumers had to the original Coke, leading to a PR disaster and a quick return to “Coca‑Cola Classic”. The lesson is that superficial testing isn’t enough; you must investigate emotional and behavioural reactions.

Common mistakes to avoid

- Overloading respondents: Testing many concepts in one survey leads to fatigue and confusion. Dovetail warns that comparing lots of concepts in a single survey makes the experience tiring.

- Poor audience definition: If you test with the wrong people, the data misleads you. Looppanel stresses screening to ensure participants match your target demographic.

- Biased questions: Leading language or inconsistent presentation can skew responses. Present each concept neutrally and at the same fidelity.

- Using concept tests to confirm a foregone conclusion: If you’re only looking for validation, you’ll find it. Welcome negative feedback; it might save your company.

- Ignoring qualitative feedback: Numbers alone don’t tell the full story. Vase points out that open‑ended responses reveal issues you didn’t anticipate.

- Failing to iterate: A single round of testing is rarely enough. Use insights to refine your concept and run additional tests as you move closer to launch.

When concept testing makes sense—and when it doesn’t

Understanding what is concept testing in marketing helps you decide when to use it. Do a concept test when:

- You’re at the idea stage and need to understand whether the problem is worth solving.

- You have multiple positioning or feature options and must choose one.

- You’re making a big bet on design or messaging and need evidence before investing further.

- You’re exploring pricing strategies or packaging changes.

Skip concept testing if:

- The idea is already mature and minor UX issues remain; you’ll get more value from usability testing, which focuses on how easily users can use the product.

- You’re making small copy tweaks or UI polish where a quick A/B test suffices.

- The timeline is too tight to recruit a representative sample.

Concept testing complements other research methods. Looppanel’s comparison with usability testing shows that concept testing evaluates what and why at an early stage, while usability testing assesses how well the product works once built. Market testing, prototype testing and positioning research all build on concept testing to create a holistic research programme.

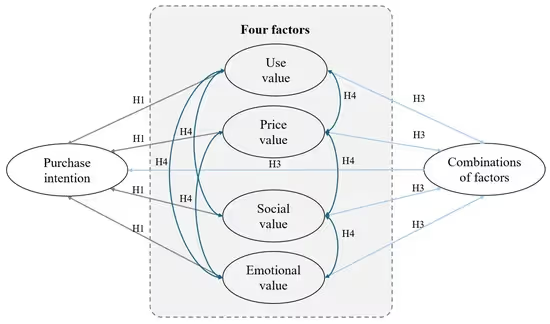

Metrics and tools

To make sense of your results, track a handful of metrics:

- Appeal or desirability: The percentage of respondents who find the concept attractive.

- Purchase intent: How likely people are to pay at a given price. This can be unpriced or priced, as Attest describes.

- Feature importance: Use conjoint analysis to see which features drive choice.

- Price sensitivity: What price feels too expensive? At what point do purchase intentions drop sharply?

- Comparison ranking: In comparative tests, which concept wins overall and by segment?

- Segmentation insights: Differences across demographics or psychographics can reveal niche opportunities.

For tools, you don’t need an enterprise research budget. Platforms like Attest, Vase, and Voxco make concept testing accessible; they offer templates, segmentation and analysis features. Looppanel’s machine‑assisted research platform and Dovetail’s insight hub help with analysis and synthesis. For prototypes, use Figma or InVision. To analyse qualitative data, consider tools like Dovetail’s repository or open‑ended coding solutions.

Final reflections

So what is concept testing in marketing at its heart? It’s not just another research box to tick. It’s a mindset of humility: recognising that your idea doesn’t matter until your customers say it does. In my experience working with early‑stage tech and SaaS founders, teams that invest a few days in concept testing avoid months of wasted effort. Those who skip this step often build impressive technology no one needs.

We’ve seen what happens when companies listen: Lego expanded its audience by asking young girls about their play patterns. Yamaha resolved a design dilemma by learning that sliders beat knobs. Tesla validated demand before designing a car by collecting deposits. And we’ve seen cautionary tales—New Coke’s collapse because Coca‑Cola ignored the emotional bond consumers had with the original recipe.

As you work on your next product, keep a simple mantra: ask before you build. Concept testing isn’t expensive; it’s the cost of curiosity. Whether you’re crafting a B2B SaaS tool, a consumer app or a marketing campaign, taking the time to test your concept will help you create something people actually want. And that’s what makes the difference between joining the 95 % of failures and landing in the rare 5 % that succeed.

FAQ

1) What does concept test mean in marketing?

When people search for what is concept testing in marketing, they often find jargon. A concept test is an early‑stage research effort where you present a proposed product, service or campaign to a carefully defined target audience and ask them about desirability, purchase intent, perceived value and fit. It helps you decide whether to develop the idea further or change direction. Dovetail describes concept testing as a research method to evaluate assumptions about customer needs and willingness to purchase.

2) What is an example of concept testing?

Lego’s research into how girls play with building sets is a classic example. By observing that girls preferred creating full environments and focusing on interior details, the company designed Lego Friends and broadened its customer base. Another example often cited is Tesla’s Model 3 deposit programme, where the company gathered 400,000 pre‑orders and validated demand before building the car.

3) What is meant by concept test?

The phrase refers to a structured study used to gauge how a new concept will perform in the market. Participants evaluate the idea’s appeal, uniqueness, usefulness and price, providing quantitative scores and qualitative feedback. The goal is to reduce uncertainty and inform product or marketing decisions. Voxco points out that concept tests survey a target audience to gauge interest, acceptance and willingness to engage with a concept.

4) What’s the difference between test marketing and concept testing?

Understanding what is concept testing in marketing clarifies this difference. Concept testing happens early, before you invest in development. It measures desirability and purchase intent based on a description or prototype. Test marketing, by contrast, occurs later; you release a finished or nearly finished product into a limited market to observe actual sales and behaviour. Concept testing looks at “what and why”, while test marketing observes “how many and how often”.

.avif)