What Is Data‑Driven Design? Guide (2026)

Learn about data‑driven design, which uses analytics and user feedback to inform design decisions and improve outcomes.

Intuition has its place in design, but by 2025 the stakes are too high to rely solely on gut feeling. Founders and product managers at early‑stage companies know that every UI choice can shape a new user’s first impression and affect scarce resources. If you’re wondering what is data‑driven design is, think of it as a practice that grounds creative decisions in evidence. Instead of hunches, teams look at how people actually behave, using numbers and stories to inform each iteration. In this piece I’ll explain why this approach matters to start‑ups, how to put it into practice, and what to watch out for. You’ll learn about benefits, the steps involved, tools to use, real‑world examples and common traps.

What does “data‑driven design” mean?

Data-driven design means basing creative decisions on evidence rather than personal opinion. The phrase what is data‑driven design describes a mindset: drawing on empirical evidence to inform design decisions instead of relying solely on intuition or personal opinion. This evidence comes in two types:

- Quantitative data—numbers that show what people do and when. Examples include analytics events, click‑through rates, funnel completion rates and A/B test results. A/B testing is a widely used quantitative method. Nielsen Norman Group explains that A/B testing splits traffic to compare design variations and uses predetermined business metrics to determine which variant performs best. This helps teams make choices based on measured behaviour rather than guesswork.

- Qualitative data—insights that explain why people act as they do. Interviews, usability sessions, surveys and session replays show motivations, emotions and context. IDEO emphasises that qualitative research is critical to understanding what data is meaningful and feasible to collect; designers need to understand people’s real needs in their context before deciding what to track.

In traditional practice, design choices were often driven by expert opinion or aesthetic taste. While expertise is valuable, it lacks objectivity. Data‑driven design ties decisions to business goals and measurable outcomes. For example, metrics like conversion rate, retention and task success connect user interactions to company performance. Mazes’s interview with Chris Linnett draws a distinction between data‑driven and data‑informed practice: the former puts hard data first, whereas the latter also considers professional experience, qualitative feedback and broader objectives. In practice, both kinds of evidence matter. You need facts, but you also need the judgement to interpret them.

Why it matters for start‑ups and product teams

When people ask me what is data-driven design in the context of start-ups, I point to the impact on speed and risk. Making changes based on evidence lets young companies learn quickly without betting the company on a hunch.

Early‑stage companies must move quickly and make the most of limited time and cash. Data helps you iterate faster and reduce risk because you’re basing changes on what users actually do, not what you hope they will do. A/B testing, for example, lets you validate variations without major overhauls, and it enables teams to make decisions that are easier to communicate to stakeholders. By linking design changes to metrics such as conversion, retention and engagement, you see whether your work contributes to revenue, sign‑ups or activation. Unbounce’s 2025 benchmark report found a median conversion rate across industries of 6.6%, and their case studies show how even small wording changes can make a big difference. In one example, travel deal startup Going doubled the rate at which users started a premium trial by testing two call‑to‑action phrases. Such leaps in performance can make or break a young business.

There’s also a human side. Good user experiences lead to happier customers and better reviews. A Forrester study referenced by Aquent found that design leaders who integrated business‑centric thinking into their processes achieved a 30% increase in customer satisfaction scores. Data‑driven design helps you identify and remove friction in onboarding flows or sign‑up pages, improving the chances that people stick around. On the flip side, focusing on vanity metrics can mislead teams. Nielsen Norman Group warns that metrics like total downloads or page views may look impressive but do not map to user experience or business goals; instead, rates and ratios provide meaningful context.

By grounding design in evidence, teams also improve communication. Decisions backed by data are easier to explain to investors and colleagues, creating shared understanding and reducing subjective debates. It also prepares teams for personalisation: Contentful reports that 89% of marketing decision‑makers consider customising experiences essential for success, yet only 60% of customers believe they currently receive personalised experiences. Data‑driven approaches make it possible to segment users and customize interfaces without guessing.

CTA: Book a call

The building blocks – what data to use and where it comes from

If you’re still thinking about what is data-driven design, the answer lies in the inputs you gather and how you use them. Evidence comes from both numbers and stories, and combining them brings you closer to your users.

To practice what is data‑driven design, you need the right inputs. Data falls into two broad categories:

Quantitative inputs

- Analytics events and funnels – Tools like Google Analytics, Mixpanel or Amplitude track visits, clicks, time spent and conversion flows. They answer “what” questions: How many users dropped off at step three? How long do they take to complete a task? Unbounce’s report, for instance, uses conversion rates to benchmark performance across industries.

- A/B and multivariate tests – As described by Nielsen Norman Group, A/B testing compares two versions of a page to see which performs better based on defined metrics. Multivariate tests examine multiple elements at once. These methods require clear hypotheses and enough traffic to reach statistical significance.

- Heatmaps and session replays – Tools such as Hotjar or FullStory show where people click, scroll or hesitate. This visualisation helps identify friction points.

- Retention and churn metrics – User retention rate measures the percentage of users who return over a set period. UXCam explains that a retention rate is worked out by dividing returning users by total users and multiplying by 100, and that small increases can substantially boost revenue. Churn rate tracks the percentage of users who stop using an app.

Qualitative inputs

- User interviews and field research – Talking to people uncovers motivations, pain points and context that numbers miss. IDEO stresses that qualitative research builds empathy and helps determine what data is meaningful.

- Usability testing – Observing people as they attempt tasks reveals friction and confusion. You can pair this with think‑aloud protocols to understand their reasoning.

- Surveys and feedback loops – Net Promoter Score (NPS) surveys gauge loyalty and satisfaction. UXCam explains that NPS is worked out by subtracting the percentage of detractors (scores 0–6) from the percentage of promoters (scores 9–10).

Data sources and instrumentation

Your data may come from web analytics, mobile app analytics, product analytics tools or custom event tracking. Session recordings capture interactions for later review. Segmenting the data by user type, device, or referral source helps you see different behaviours. Cohort analysis shows how retention or usage varies over time. Frameworks such as Google’s HEART model help structure this measurement. Statsig’s overview of HEART explains that it covers five dimensions—happiness, engagement, adoption, retention and task success—and uses a goals–signals–metrics process to translate objectives into actionable metrics. Choosing the right measurement framework ensures that you track what matters and don’t drown in numbers.

A step‑by‑step process for data‑driven design

The path to practising what is data-driven design involves a sequence of steps that start with goals and end with iteration. Putting what is data‑driven design into practice involves a repeatable cycle. Here’s a process we use at Parallel with early‑stage clients:

- Define goals and hypotheses. Start by identifying the problem you want to solve. Is your sign‑up flow losing new users? Do people fail to complete onboarding? Set a hypothesis like “reducing the number of fields on the sign‑up page will increase completion rate.” Choose metrics that reflect success—conversion rate, task completion time or retention. It’s helpful to use frameworks such as HEART or CASTLE to map goals to signals.

- Collect and analyse data. Instrument your product to capture relevant events. For example, track when users start and finish onboarding steps. Use analytics to segment by device or user type. Examine funnels to find drop‑offs. Review session replays to understand friction. Look for patterns: Are people abandoning the form at a specific question? Are they returning later?

- Generate design hypotheses. Based on your insights, propose changes. If you see a high drop‑off at step two, hypothesise that simplifying or reordering fields will improve completion. Combine quantitative findings with qualitative insights from interviews. Mazes’s article emphasises that combining hard data with professional experience and qualitative feedback yields better decisions.

- Design and experiment. Create prototypes or variations of your design. For small changes, an A/B test may suffice; for larger changes, consider multivariate tests. Nielsen Norman Group advises keeping variations focused so that you can isolate which element drives performance. During the experiment, split traffic so that each version has enough samples. Use design tools like UXPin to connect prototypes to real data and gather early feedback.

- Implement and measure outcomes. Once the experiment ends, analyse the results. Did the variant outperform the control? Do the results meet statistical significance? If the variant improves your metric, roll it out. If not, either stick with the original or test another idea. Document your learnings.

- Iterate and scale. Data‑driven design is not a one‑time project. Use the insights from each test to inform further improvements. Apply successful patterns to other parts of your product, personalise experiences for different user segments, and continue measuring. Early‑stage companies benefit from this loop because it ensures that investments in design are tied to measurable outcomes.

Practices and principles for effective data‑driven design

To make the most of what is data-driven design, keep these practices in mind.

1) Balance evidence and creativity

Numbers reveal patterns, but creativity translates those patterns into compelling experiences. Data should inform, not dictate. Maze’s interview with Chris Linnett describes data‑driven practice as putting hard data at the centre while still considering other inputs like professional judgment and business goals. Use data to validate your ideas, but leave room for experimentation.

2) Personalise responsibly

Modern users expect customised experiences. Contentful states that 89% of marketing decision‑makers see personalisation as essential. Personalisation requires segmenting your audience and delivering variations that speak to their context. However, take care not to over‑segment or rely on stereotypes. Always measure whether personalisation improves performance and user satisfaction.

3) Build continuous feedback loops

Data‑driven design thrives on feedback. Incorporate analytics and user feedback into every stage of your process. After releasing a change, monitor metrics and talk to users. Set up dashboards that surface trends. UXCam suggests combining quantitative metrics like retention with qualitative insights from session replays to identify why users churn.

4) Avoid vanity metrics

Metrics should be actionable. Nielsen Norman Group warns that counts such as total downloads or page views may appear impressive but don’t provide insight into user experience. Instead, track rates and ratios: conversion per session, active users per week, or retention over time. Use metrics you can influence through design, and ensure they connect to business objectives.

5) Communicate clearly

Data is only useful if stakeholders understand it. Present insights in simple language and visuals. Explain what the numbers mean and why they matter. A Forrester study showed that design leaders who tie design work to business‑centric objectives achieve higher customer satisfaction. Build stories around your data to inspire action.

6) Ensure data quality and ethics

Data quality matters. Poor instrumentation or sampling bias leads to wrong conclusions. Use clean event definitions and verify that your analytics tools capture what you expect. Respect privacy and comply with regulations. Personalisation must be transparent, and users should be able to opt out. When working with machine‑learning models, monitor for bias and fairness. Though advanced analytics can suggest patterns, designers remain responsible for final decisions.

Tools and techniques to support data‑driven workflows

Many designers wonder what is data-driven design when selecting software; the answer is choosing tools that support measurement and experimentation so that decisions are informed by evidence.

There is no universal toolkit, but several categories of software can help you practice what is data‑driven design:

- Analytics and tracking platforms – Google Analytics, Mixpanel, Amplitude and Statsig capture events, segment users, and provide dashboards. Statsig also supports experimentation and uses frameworks like HEART to structure metrics.

- UX research and usability tools – Hotjar, FullStory and UXCam offer heatmaps, session replays and in‑app surveys. They help you see where users hesitate and why they abandon flows. Session replays let you watch real interactions.

- Experimentation frameworks – Tools such as Optimizely, VWO and Statsig enable A/B and multivariate testing. They support sample size calculations and statistical analysis. Many modern product analytics platforms integrate experimentation directly.

- Data visualisation and dashboards – Platforms like Tableau, Looker or Mode connect to your data warehouse and create charts and reports. You can build customised dashboards to monitor conversion funnels, retention cohorts or feature adoption. At Parallel, we often embed such dashboards into weekly reviews.

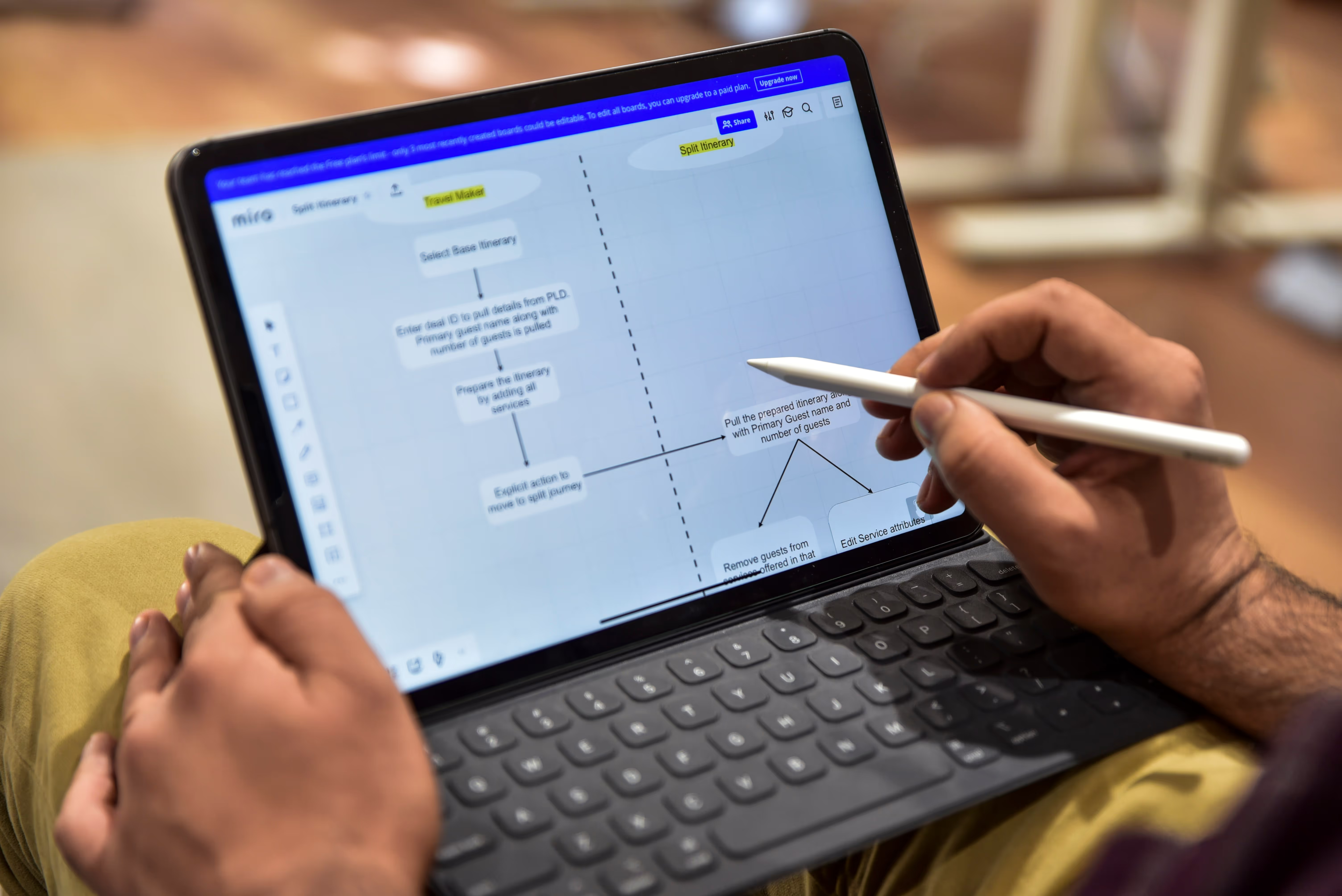

- Design tools connected to data – UXPin and Figma can pull real data into prototypes. This helps teams test interactions with realistic content and conditional logic, improving fidelity before development.

When choosing tools, consider your company’s stage, technical resources and goals. Start with one analytics platform and one testing framework before adding more complexity. Integrate your design and engineering workflows so that data moves smoothly between them.

Practical examples and case studies

Early start‑up: Reducing onboarding friction

One of Parallel’s clients, a machine‑learning‑powered SaaS product, struggled with onboarding completion. Only 45% of new users finished setting up their first model. We instrumented the onboarding flow to track completion of each step and recorded session replays. Analysis showed that most users abandoned the process at a step that required copying an API token from a separate console. Interviews revealed that switching tabs caused confusion and some users felt nervous about exposing secrets. Our hypothesis was that embedding a one‑click integration would reduce friction. We created two designs: one with a simple “Connect to data source” button and another that still required manual copy‑and‑paste. We ran an A/B test and saw the embedded button variant improve completion rate to 68%, a 23‑point increase. The change also reduced support tickets related to onboarding. This simple experiment paid off because we targeted a specific pain point and measured the outcome.

Case study: Changing CTA text at a travel start‑up

Unbounce’s 2025 compilation of conversion case studies includes a striking example. Travel deal service Going wanted more users to try its premium tier. The team hypothesised that changing the call‑to‑action copy from “Sign up for free” to “Trial for free” would prompt more users to start a paid trial. They tested both phrases using an A/B test and found that the shorter “Trial for free” call‑to‑action produced a 104% month‑over‑month increase in premium trial starts. This result shows how wording can influence user behaviour and demonstrates the value of systematic testing.

Enterprise example: Structuring metrics with HEART

Statsig’s overview of the HEART framework describes how Google measures user experience across five dimensions—happiness, engagement, adoption, retention and task success—and uses goals, signals and metrics to translate objectives into measurements. In our work with a large enterprise client, we adapted HEART to evaluate an internal tool used by hundreds of employees. For “happiness,” we used an internal satisfaction survey. For “engagement,” we measured frequency of use. For “adoption,” we tracked how many teams switched from spreadsheets to the new tool. For “retention,” we looked at weekly active users over time. For “task success,” we measured error rates and time to complete workflow steps. This structure helped leadership see how design changes affected productivity and morale. It also revealed that while adoption was high, task efficiency lagged because some workflows were too complex. Redesigning those flows improved both efficiency and satisfaction.

Personalisation and customer loyalty

Contentful’s 2025 study on personalisation found that 95% of senior marketers consider their personalisation strategies successful and that 89% of decision‑makers see customising experiences as essential. However, 85% of companies believe they provide personal experiences while only 60% of customers agree. This gap reflects the opportunity for product and design teams. Data‑driven design enables personalisation by segmenting users and delivering content or layouts that match their intent. For example, Netflix uses viewing history to propose shows and tunes the homepage layout based on past engagement. These suggestions are constantly tested and refined using A/B experiments. Without data, such adaptive personalisation would not be possible.

CTA: Book a call

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Overreliance on quantitative data. Numbers show what happened but not why. Combine metrics with user interviews and session replays to understand motivations. IDEO warns that designers must be part of research to grasp what data is meaningful.

- Misinterpreting signals. Correlation is not causation. For example, a spike in conversion may coincide with a marketing campaign rather than a design change. Ensure that your tests are properly controlled.

- Paralysis by analysis. Having too many metrics can slow decision‑making. Use frameworks like HEART to select a few meaningful measures and ignore vanity metrics.

- Ignoring creativity. Data should inform, not replace, design intuition. Leave space for experimentation and serendipity.

- Choosing wrong metrics. Avoid tracking metrics that always go up but don’t reflect user experience. Instead of measuring total sign‑ups, measure the ratio of active users to sign‑ups.

- Missing feedback loops. A/B testing without follow‑up can lead to unintended consequences. Monitor metrics over time and gather qualitative feedback to ensure long‑term success.

- Not matching business goals. Metrics should map to outcomes that matter to your company. Forrester research shows that when design is tied to business‑centric objectives, customer satisfaction improves.

What’s next in 2025 and afterwards

The next few years will bring higher expectations for personalised, user‑centric experiences. Machine‑learning models are increasingly integrated into product analytics, offering predictive insights and automated experimentation. For early‑stage companies, this means that even small teams can test many variations and adjust in near real time. At the same time, privacy and ethics are becoming more prominent. Regulations require transparent data collection and give users control over their information. Designers will need to balance personalisation with respect for privacy.

Design leaders will play an expanded role in championing data‑driven practices. A McKinsey Design Index study cited by Aquent shows that companies in the top quartile of design maturity see 32% higher revenue growth and 56% higher total return to shareholders. As investors and executives recognise this link, designers will be expected to tie their work directly to metrics like adoption, retention and satisfaction. At the same time, tools will continue to democratise experimentation. Even non‑technical teams will be able to run controlled tests using low‑code platforms. The winners will be those who build habits of continuous measurement and empathy.

Conclusion

Data‑driven design is about grounding creative work in evidence. When asked what is data‑driven design is, I answer that it means using both quantitative metrics and qualitative insights to guide decisions rather than trusting gut feeling alone. This approach helps early‑stage founders and product leaders iterate quickly, reduce risk and connect design choices to business outcomes. By defining goals, collecting and analysing data, generating hypotheses, experimenting, measuring results and iterating, teams build products that people love and that deliver measurable impact. The challenge is to balance facts with creativity, avoid vanity metrics and embed continuous feedback loops. Start small: pick one metric that reflects your objective, instrument your product, run a simple test and use what you learn to improve. With patience and curiosity, you’ll create an environment where every design decision becomes an opportunity to learn.

FAQ

1. What is the meaning of data‑driven design?

It refers to the practice of using real evidence—both numbers and stories—to inform design decisions instead of relying solely on intuition. By analysing how users actually behave and what they say, teams can make changes that solve real problems.

2. What is data‑driven in simple words?

It means making choices based on evidence from user behaviour and feedback rather than guesses. For example, if analytics shows that 60% of visitors leave a sign‑up page at a particular field, you redesign that field to improve completion.

3. What is the data‑driven design process?

A typical cycle involves setting goals and hypotheses, collecting and analysing both quantitative and qualitative data, generating design hypotheses, testing them through experiments like A/B tests, implementing the winning variant, measuring outcomes and iterating.

4. What is an example of a data‑driven model?

Suppose you notice that new users drop off during onboarding. You segment the data and conduct interviews, discovering friction at the second step. You redesign that step and test the new version against the old. The test shows a significant improvement in completion rate, so you adopt the new design. This is a simple model of data‑driven decision‑making in design.

.avif)