What Is a Design Sprint? Guide (2026)

Learn about design sprints, a process that helps teams rapidly solve problems and test ideas in just five days.

Many early‑stage startups waste time and money trying to fix product and user‑experience problems without validating their assumptions. This guide answers the question what is a design sprint by showing how a short, structured workshop can help teams test ideas quickly and reduce risk. The article draws on practitioner experience, recent research and case studies to explain why this approach matters for founders, product managers and design leaders.

What is a Design Sprint?

A Design Sprint is a 5-day, highly structured workshop for solving big problems, validating ideas, or figuring out product/design direction before spending too much time or money building.

Where it came from

The design sprint was developed by Jake Knapp at Google Ventures (GV) as a way to compress months of product development into a single week. GV combined techniques from business strategy, behaviour science, lean thinking and design thinking to build a battle‑tested process that teams could reuse. This method grew out of frustrations with endless debates and slow decision‑making; the goal was to give teams a shortcut to learning without having to build and launch full products.

Influences from related practices

Several movements informed the sprint. Design thinking emphasises empathy and iterative problem solving. Lean startup principles focus on building only what is needed to test hypotheses. Agile methods encourage short cycles and collaboration. The sprint borrows from all of these: it uses user‑centered research to pick a focus, rapid prototyping to build just enough to test, and a tight schedule to maintain momentum. The method has since been adopted by startups and large companies alike as a way to address complex challenges.

Why it matters for product teams

Startups often operate under uncertainty. They must decide whether to pursue an idea before they have data. A design sprint provides a structured way to answer critical business questions in five days. It compresses problem framing, ideation, prototyping and user testing into a single week. Because the process involves cross‑functional participants—designers, product managers, engineers and business stakeholders—it helps bring everyone onto the same page. Instead of debating in abstract, teams test a realistic prototype with users and decide their next steps based on evidence.

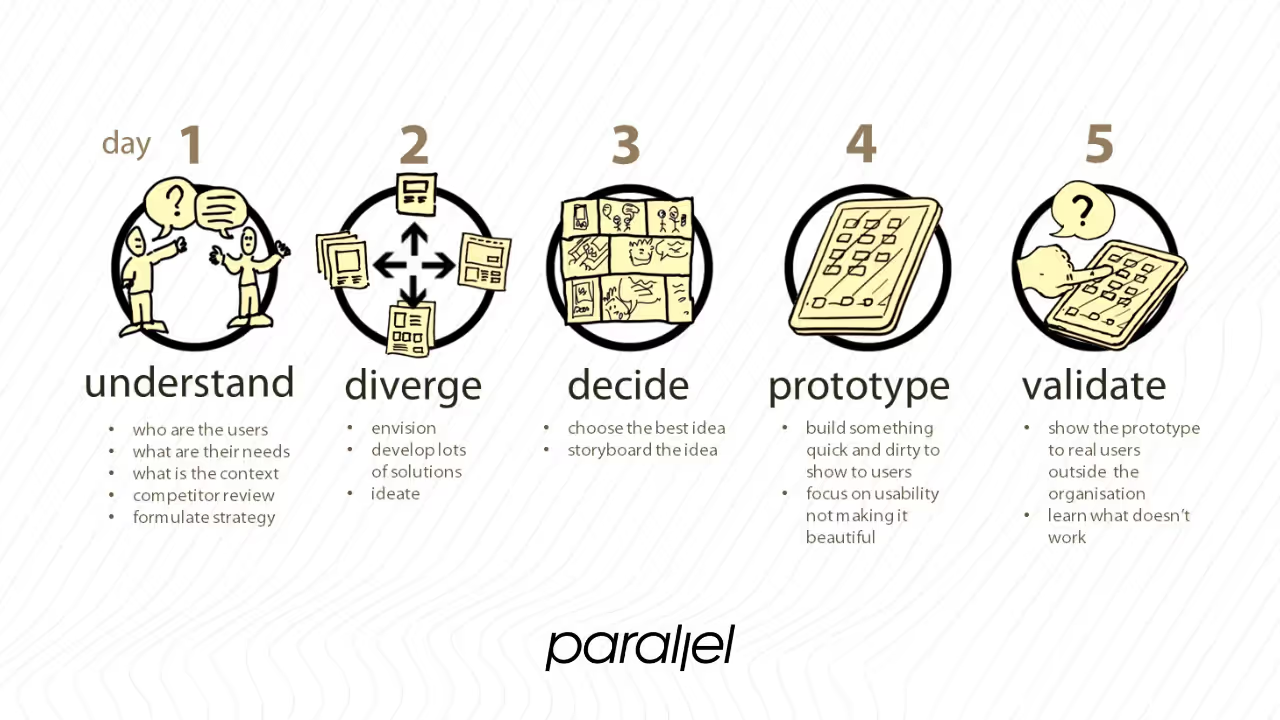

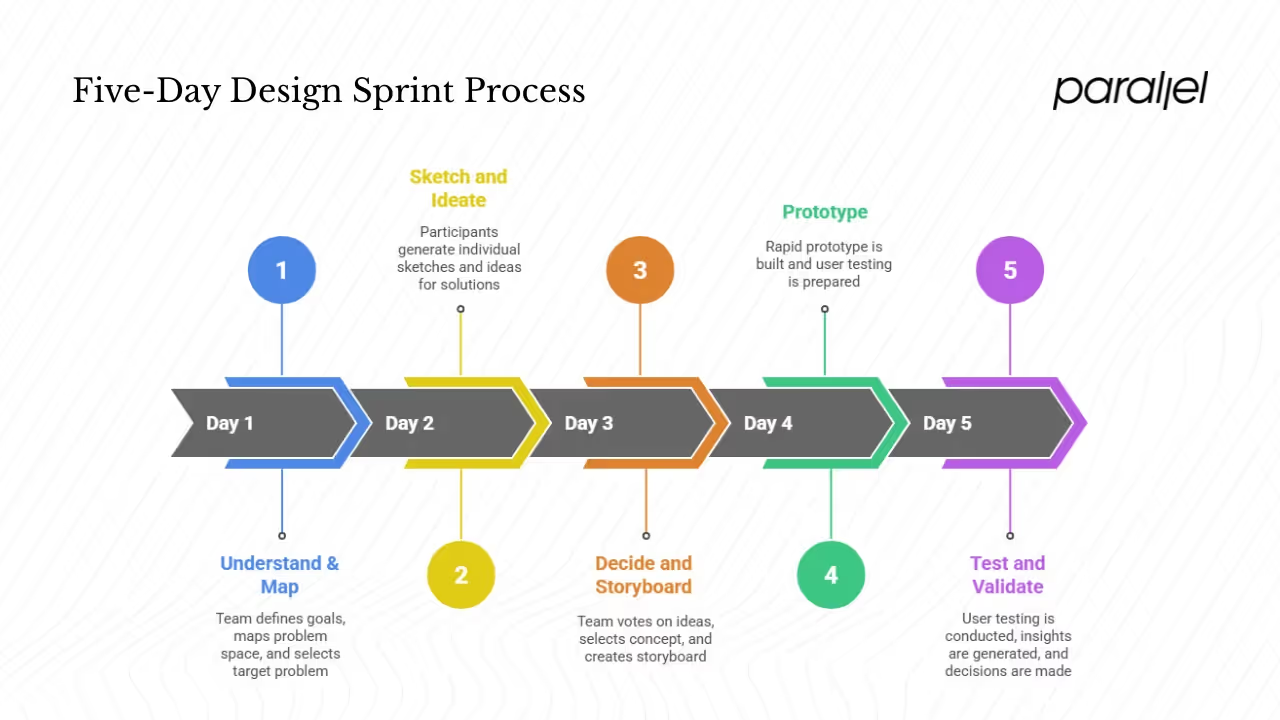

Design sprint: five‑step process

A classic sprint spans five days and follows a sequence of steps. Each day has a distinct purpose and set of outputs.

Day 1 – Understand & map

- Goal setting and mapping – The team defines a long‑term goal and identifies the key questions they need to answer. They map the problem space to understand the customer’s interactions and where the most critical pain points li.

- Expert interviews and research – Subject‑matter experts share insights about users, business constraints and technology considerations. The team may review user interviews, analytics and competitive research to ground their understanding. By the end of the day, the group chooses a target problem that offers the biggest opportunity for impact.

Day 2 – Sketch and ideate

- Individual idea generation – Participants work separately to produce sketches or storyboards. Techniques like “How might we …?” questions and the Crazy 8s exercise encourage divergent thinking so that a wide range of ideas surfaces. Avoid group brainstorming at this stage to reduce group‑think and encourage novel solutions.

- Output – The day ends with a set of sketches representing different approaches to the problem.

Day 3 – Decide and storyboard

- Critique and voting – The team reviews the sketches and uses structured voting (dot voting or heat maps) to identify promising ideas. Discussion focuses on feasibility and impact.

- Storyboard creation – Once a concept is chosen, participants create a step‑by‑step storyboard describing how a user will interact with the solution. This acts as a blueprint for the prototype.

- Outcome – By day’s end the team has a clear hypothesis to test and a plan for building the prototype.

Day 4 – Prototype

- Rapid prototyping – A realistic but lightweight prototype is built. It should emulate the user experience enough to get valid feedback. Simple tools like Figma, Marvel or even slide decks can suffice, as long as the prototype looks real to participants.

- Test preparation – The team writes an interview script and recruits five users (a number backed by Nielsen and Landauer’s research showing that testing with five users uncovers about 85% of usability problems). They schedule sessions for the next day.

- Outcome – At the end of day 4 there is a testable prototype and a plan for interviews.

Day 5 – Test and validate

- User testing – The team conducts one‑on‑one sessions with users, observing how they interact with the prototype. They capture behaviours, questions and points of confusion. Quick synthesis between sessions helps spot patterns.

- Insight generation – After the tests, the team discusses what they learned. They identify which parts of the hypothesis were validated and which need rethinking.

- Decision – Based on evidence, the team decides whether to proceed, iterate or pivot. This decision feeds into the product roadmap.

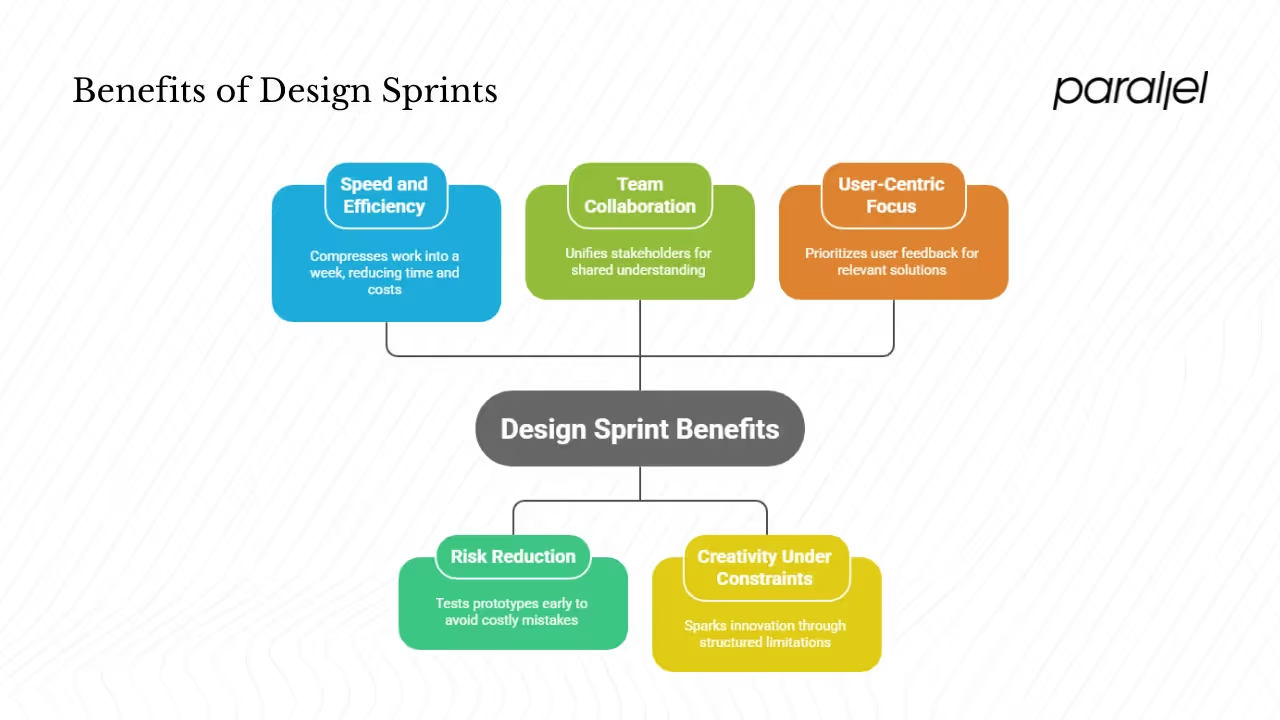

Why run a design sprint? Key benefits

1) Speed and efficiency

Design sprints compress months of work into a week. According to Goji Labs, studies show that sprints can reduce development time by 30–40 percent. Companies have reported cutting development costs by roughly 15 percent when using sprints. This efficiency comes from focusing on the riskiest parts of an idea, prototyping only what is needed and making decisions quickly.

2) Risk reduction

Building products without validating them is risky. By testing a prototype with users, teams learn which assumptions are wrong before they invest in full development. This reduces the chance of releasing features nobody wants. The sprint’s time box ensures that testing happens early, not after months of coding.

3) Bringing people together

Because a sprint involves cross‑functional participants, it helps unify stakeholders from design, product, engineering and business. Working together on a structured schedule reduces siloed decision‑making. By the end of the week, everyone has a shared understanding of the problem and the proposed solution.

4) Encouraging creativity under constraints

The structured agenda pushes participants to think broadly before narrowing down options. Individual sketching produces varied ideas, while the voting process helps the team agree on a single direction. The constraint of time sparks creativity and prevents over‑polishing early drafts.

5) Keeping users at the center

User testing is the final and most important part of the sprint. This focus on real user feedback ensures that the concept is grounded in actual needs rather than internal assumptions. The Nielsen Norman Group’s research shows that testing with just five participants can uncover a large share of usability issues, making a short sprint feasible.

When it works and when it doesn’t

Ideal scenarios

A design sprint shines in situations with high uncertainty and potential for big impact:

- New products or features – When launching something new, you need clarity on whether users want it. A sprint can quickly test appeal before investing heavily.

- Confusing flows or poor metrics – If analytics or support data show that users are stuck in an experience, a sprint can help rethink that flow.

- Entering a new market – A sprint can test assumptions about a new audience without building a full offering.

- Redesigns or rebrands – When rethinking an existing product, a sprint helps ensure that updates meet current user needs.

- Strategic uncertainty – When there are multiple possible directions and the team needs evidence to pick one, a sprint brings focus.

Less suitable situations

A sprint is not right for every problem. Minor interface tweaks or well‑understood issues might not justify the effort. Problems that require deep technical research or infrastructure changes may need longer exploration. If the right decision‑makers or domain experts cannot commit to being in the room, the sprint loses power. Likewise, if the challenge is not well‑framed, the group may spend the week chasing the wrong question.

Trade‑offs

A sprint demands a full week of undistracted attention from a cross‑functional team. This can disrupt regular work and requires planning. The prototype created during the sprint is deliberately lightweight; some stakeholders may expect more. Outcomes depend heavily on the quality of the problem statement and the diversity of perspectives in the room. Poor preparation can lead to superficial solutions.

Preparation: roles, team setup and logistics

Roles and responsibilities

- Facilitator – Guides the team through the process, enforces time boxes and keeps discussions focused.

- Decider – Often the founder or product lead. This person makes final calls when the group is split.

- Design/product lead – Brings user‑experience expertise and helps define the problem. They may run the prototyping on day 4.

- Engineer – Provides technical insights and ensures the prototype is feasible.

- Business stakeholder – Offers context on business goals and constraints.

- UX researcher – Helps plan user tests and interpret feedback.

Team size and mix

A sprint works best with five to eight participants. This number balances variety of viewpoints with the ability to make decisions quickly. The mix should include people who understand the user, the business and the technology. At least one decision‑maker must be present; without them, the sprint may stall.

Logistics and environment

Prepare a dedicated space for the week: a large room with whiteboards, sticky notes and enough wall space to hang sketches. For remote teams, use virtual whiteboarding tools like Miro or MURAL and a reliable video‑conferencing platform. Protect time by blocking calendars. Participants should not be pulled into other meetings during the sprint.

Before the sprint begins, gather existing research, analytics and stakeholder input. This material informs the problem framing and prevents re‑hashing known facts during the workshop. Recruit five users fitting the target profile and schedule interviews for day 5.

Variations and adaptations

Shortened sprints and remote versions

While the classic GV model runs for five days, many teams adapt the schedule. A four‑day sprint compresses the Understand and Sketch phases into one day. Half‑day kick‑offs can be used when participants cannot commit to full days. Remote sprints spread sessions over several weeks with shorter blocks to account for time‑zone differences. The core principles remain: clear problem framing, individual idea generation, group decision‑making, prototyping and testing.

Artificial intelligence design sprints

As machine‑learning products become more common, some teams run “artificial intelligence design sprints.” These follow the same structure but include additional considerations:

- Data and model scope – Define what data is available and how models will be trained. Limit the problem so that a prototype can be built without production‑level pipelines.

- Ethics and bias – Discuss potential biases in data and modelling and how to mitigate them. Engage legal and ethics experts early.

- User trust – Prototype ways to explain predictions or recommendations to users, since transparency is crucial in machine‑learning products.

Enterprise versus startup

Large organizations often have more stakeholders and complex decision chains. An enterprise sprint may involve separate pre‑work sessions to gather input from multiple departments and ensure commitment. Startups can move faster but still need to involve the right stakeholders to avoid blind spots.

Distributed teams

Remote teams can run effective sprints by relying on digital collaboration tools and clear communication. Keep sessions short to avoid fatigue. Use templates for sketching and voting, and make sure everyone has a microphone and camera. Encourage informal check‑ins to build rapport when working apart.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Vague problem framing – If the challenge is not specific, the sprint will produce unfocused solutions. Spend time defining the long‑term goal and the questions you need to answer.

- Missing expertise – Leaving out key domain experts or decision‑makers means the group may build a prototype that cannot be delivered. Involve those who understand the customer, technology and business.

- Over‑polishing the prototype – The prototype should be realistic enough to test, not a production‑ready product. Focus on the core flow and interactions. Avoid getting stuck on details.

- Ignoring user feedback – Confirmation bias is a risk. Listen carefully to test participants and adjust your thinking based on evidence, even if it contradicts your favourite ideas.

- Underestimating resources – Sprints require preparation and follow‑through. Allocate time for planning, recruiting users and synthesising insights. After the sprint, schedule time to iterate on the prototype.

- Lack of follow‑through – A sprint is pointless if insights are not acted on. Add findings to the product backlog, create a plan for iteration and involve leadership to carry decisions forward.

Measuring success and what comes after the sprint

Metrics and indicators

Success depends on more than whether users liked the prototype. Look for:

- Quality of user feedback – Did participants understand the concept? Were there clear moments of confusion or delight?

- Clarity on next steps – Does the team know whether to proceed, iterate or pivot?

- Validated hypotheses – Did the test confirm or refute assumptions? Document what you learned.

- Business impact – If the concept moves forward, track metrics such as conversion, engagement or revenue. In some cases, early research can indicate a lift in metrics: for example, Airbnb rethought its booking flow and saw a 10 percent increase in bookings.

- Costs saved – Compare the sprint investment to the potential cost of building the wrong feature. Companies that adopt sprints often report reducing development costs by around 15 percent.

Post‑sprint decisions

After the sprint, decide whether to:

- Go ahead – If feedback is positive and the team is confident, commit resources to build a minimal viable product.

- Iterate – If some parts worked and others didn’t, run a follow‑up sprint or iterate on the prototype.

- Pivot or drop – If the concept failed to solve the problem, thank the team and move on. Recognize that learning what not to build saves time and money.

Incorporating insights into product development

Make sure sprint learnings influence the product roadmap. Integrate validated user flows into design systems and share insights across teams. Use agile ceremonies like backlog grooming and sprint planning to turn sprint outputs into deliverable tasks. Keep the habit of testing early and often; run further research to refine the concept as it grows.

Case examples

Real stories show how design sprints work in practice. Here are two examples from well‑known companies and one from our own experience.

Slack refines its messaging platform

When Slack was expanding its messaging tool, the team ran a design sprint to examine how new users onboard. They built a prototype of the sign‑up and first‑use flow, tested it with users and discovered that people wanted clearer instructions for creating channels. Based on feedback, Slack simplified the flow and introduced guidance within the product. This sprint helped the company refine its core experience before launching at scale.

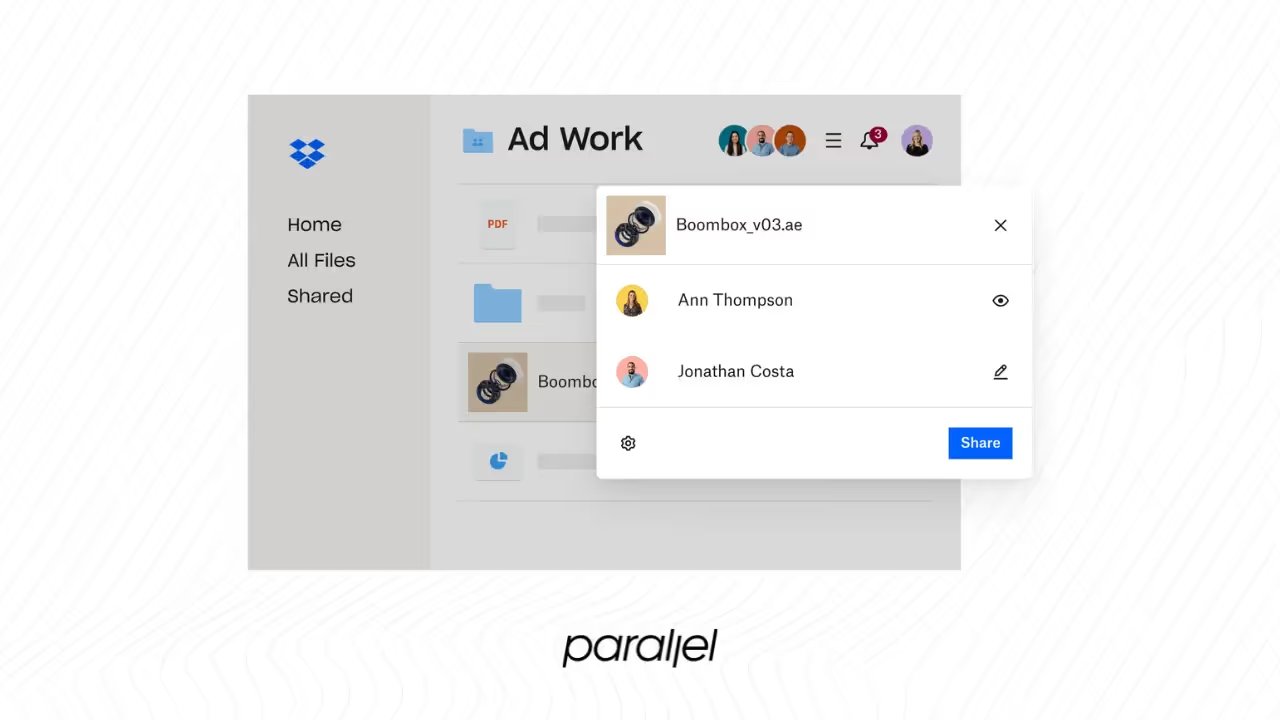

Dropbox validates demand with a video

Dropbox famously tested its file‑sharing concept with a simple video during a design sprint. The prototype wasn’t a working product; it was a narrated demo showing how the service would work. Potential customers loved it and signed up for updates. This evidence convinced the founders that the idea had legs, leading to a full build.

A hypothetical B2B SaaS startup

At Parallel, we worked with an early‑stage SaaS platform that wanted to improve its onboarding for enterprise clients. The team kept adding features, yet customers still complained about a steep learning curve. We proposed a sprint.

- On day 1, the team mapped the enterprise buyer’s experience from initial contact through first use.

- On day 2, they sketched different approaches, including guided tours, role‑based dashboards and quick‑start templates.

- By day 3, they chose a concept focusing on a lightweight “getting started” checklist integrated into the product.

- A clickable prototype was built on day 4 and tested with five real customers on day 5.

Feedback showed that the checklist reduced confusion and helped users achieve value faster. The startup implemented the checklist and saw a reduction in support tickets and an increase in activation within the first month. This case illustrates how a sprint can bring clarity and confidence in a short time.

Conclusion

Answering what is a design sprint reveals more than just a process; it shows a mindset that favours evidence over guesswork. A sprint is a structured, time‑boxed workshop that takes a team from problem framing to user‑tested prototype in five days. It draws on design thinking, lean practices and agile principles to provide a focused path for innovation. For founders and product leaders, running a sprint can mean the difference between building something people want and building something they never use.

A sprint is not a silver bullet; it takes discipline, preparation and commitment from the right people. But used thoughtfully, it can reduce risk, speed up decision‑making and put your users at the heart of your product strategy. The next time you’re staring at a blank roadmap or debating which feature to build, pause and ask yourself what is a design sprint. Then gather your team, clear a week and find out. You might be surprised at how much progress you can make in five days.

FAQ

1) What are the five steps in a design sprint?

The classic sprint follows five phases: 1) Understand and map, where the team defines goals and maps the problem; 2) Sketch and ideate, when individuals generate ideas; 3) Decide and storyboard, where the group critiques solutions and picks one to prototype; 4) Prototype, when a realistic mock‑up is built; and 5) Test, where the prototype is tested with real users.

2) What does a design sprint look like?

A sprint is a busy week. Each day has a focus: on day 1 you set goals and map the problem, on day 2 you brainstorm individually, on day 3 you decide on a solution and draw a detailed storyboard, on day 4 you build a prototype and on day 5 you test it with users. The team works together in a single space or virtual room, using whiteboards, sketches and prototypes to visualise ideas. At the end of the week, there’s concrete feedback from users and a decision on what to do next.

3) How many days is a design sprint?

A traditional sprint runs for five consecutive days. Variations exist—some teams run four‑day sprints or split sessions across two weeks—but the core idea is to dedicate a focused block of time to move from problem to tested solution.

4) What is an artificial intelligence design sprint?

An artificial‑intelligence sprint adapts the core sprint process for machine‑learning products. In addition to the usual steps, teams consider data sources, model design, ethics and transparency. They define the scope of the model, address bias, and prototype explainability features so users trust automated decisions. The sprint still lasts about a week but involves specialists in data science and ethics.

5) What tools are best for design sprints?

For in‑person sprints, you need whiteboards, sticky notes, markers and space to display sketches. For remote sprints, use virtual whiteboarding tools like Miro or MURAL, messaging platforms for quick communication and prototyping tools like Figma or Sketch. For user testing, services like Lookback or Maze help record sessions and gather feedback.

6) How do you pick users for prototype testing?

Recruit participants who reflect your target audience. Look for variety in roles, goals and behaviours. Five participants are often enough to uncover most usability issues. Screen participants ahead of time and schedule interviews on day 5 of the sprint. Offer incentives and ensure sessions are recorded for later analysis.

7) How often should a team run design sprints?

There’s no one‑size‑fits‑all answer. Use sprints when facing major decisions, new product ideas or uncertain directions. Some teams run one or two sprints per quarter; others use them at the start of new initiatives. Avoid running too many back‑to‑back sprints, as they require energy and focus. Instead, treat them as a strategic tool to answer high‑impact questions.

.avif)