What Is a Diary Study? Guide (2026)

Discover diary studies, longitudinal research methods that capture user behaviors and experiences over time.

Imagine handing your early adopters a simple way to log what they really do with your app each day. Rather than asking them to remember what happened last week, you see their thoughts, frustrations and small wins unfold in real time. That’s the promise of a diary study: participants self‑report experiences, behaviours and feelings over a period of days or weeks in their natural setting. This guide explains why diaries matter for early‑stage founders and product teams, how to plan them, and how to make sense of the data.

What is diary study?

A diary study is a research method where participants log their thoughts, actions, or experiences over a set period while using a product or performing relevant tasks. The goal is to understand how people actually interact with a product in their natural environment, not just in a lab or one-time interview.

Example

Say you’re designing a fitness tracking app. A diary study could involve participants logging each time they use the app for two weeks—what they were doing, how they felt, and what worked or didn’t. This might uncover insights like “users ignore reminders after day three” or “they only check the app after workouts, not before.”

Why bother with diary studies?

Traditional usability tests or surveys capture a snapshot. A diary study, by contrast, provides a longitudinal view—seeing how user behaviour evolves over days or weeks. Bolger, Davis and Rafaeli note that diary methods capture the particulars of experience in a way that other designs cannot. Participants log events as they occur, reducing the recall bias that affects retrospective interviews. For founders and product managers working on early releases, this matters because you can observe how adoption, adaptation and abandonment play out in the real world.

When do they work best?

A diary study is most useful when you need to:

- Track changes over time. Clay Design Agency notes that diary studies reveal how needs and behaviour change over weeks or months. This longitudinal insight helps teams decide whether the onboarding friction you fix today still matters a month later.

- See behaviour in context. Real‑world context matters: participants log experiences as they occur, showing constraints, distractions and motivations that lab‑based studies miss. When we worked with a health‑tech startup, a diary study showed that users often started sessions on mobile during transit and then resumed on desktop at home—an insight hidden from analytics alone.

- Understand complex journeys. Long adoption cycles or multi‑stage workflows can’t be captured in a single session. Diary studies let you map experiences across stages, revealing friction points and delights in the customer path.

- Capture emotional and motivational signals. Short surveys rarely uncover underlying feelings. Daily entries reveal hidden emotions and motivations, informing product decisions. During a recent project with an AI‑powered writing tool, participants’ diary notes revealed anxiety about publishing errors—leading us to prioritise clearer feedback and undo features.

Advantages and trade‑offs

Clay’s guide lists several advantages: rich, contextual data, participant‑led insights and flexibility in formats. LogRocket adds that diary studies require fewer resources than some other UX methods and provide real‑life context. Another benefit is scale: because entries are asynchronous, you can involve ten or more participants without scheduling moderating sessions.

There are downsides. Participant fatigue and attrition are real risks. Piasecki and colleagues caution that electronic diary methods require careful design to avoid overwhelming participants. Data quality varies; some participants will write essays while others provide terse notes. Analysis is labour‑intensive, and poor prompting can lead to missed information. Despite these challenges, the depth of insight often justifies the effort.

Understanding core terms and variants

Before planning your first study, it’s helpful to define a few terms:

- Longitudinal research: following the same participants over time to observe changes.

- Self‑report: participants record their own actions, thoughts and feelings rather than being observed.

- Daily logging: regular entries, often once or more per day, though event‑based prompts are also common.

- Event‑based vs time‑based: event‑based diaries ask participants to log each time a trigger event occurs (for example, every app login), whereas time‑based diaries prompt entries at fixed intervals. Mixed approaches are possible.

- Open vs structured diaries: open diaries allow free‑form entries; structured diaries provide prompts or scales. Clay notes that open diaries capture spontaneous insights while closed diaries yield more focused, comparable data.

- Digital vs paper: mobile apps or web forms enable photos, videos and timestamps. Paper diaries can work when digital access is limited.

Diary studies are cousins of the experience sampling method (ESM) and ecological momentary assessment (EMA). These methods emphasise capturing experiences in the moment and are often used in psychology and health research. The mental‑health study by McCombie and colleagues shows how digital diaries empower self‑expression and flexibility—values product teams should honour when designing prompts.

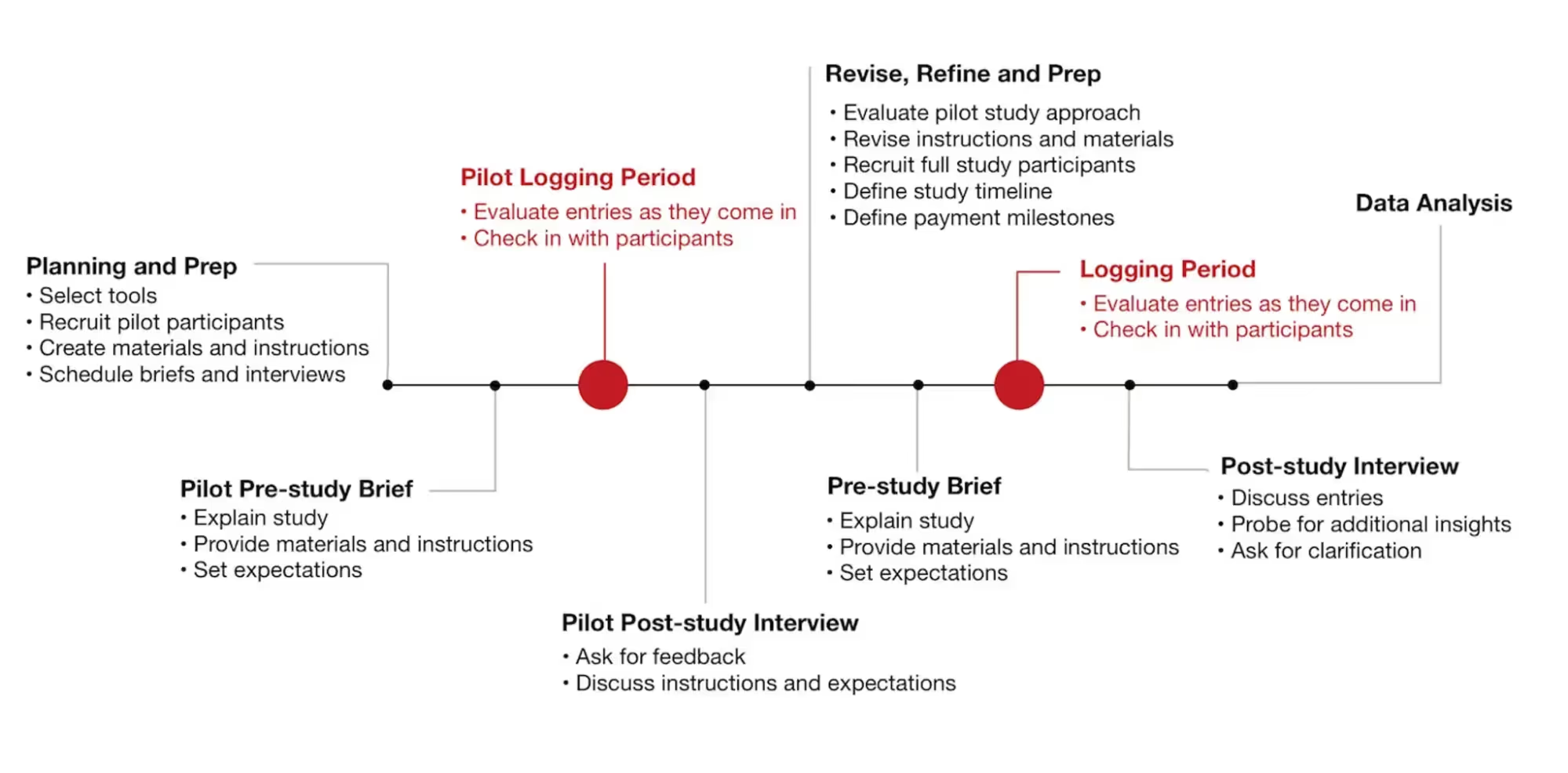

Planning your diary study

Running a diary study requires careful upfront design. Here’s a step‑by‑step plan based on our own projects and best practices from research literature.

1. Set clear objectives

Define the behaviours or experiences you want to understand. Are you exploring onboarding friction? Feature adoption? Emotional engagement? Clay suggests framing a specific research question to guide the study. Decide how the diary will complement other methods: will you combine it with interviews, analytics or surveys?

Choose an appropriate timescale. Many UX diaries run 2–4 weeks. Shorter studies can miss behavioural shifts; longer studies risk fatigue. Consider whether daily entries, weekly summaries or event‑based logging make sense for the behaviour you are tracking.

2. Recruit participants

Diary studies typically involve 10–15 participants. This number balances diversity with manageable analysis. Screen participants for commitment: they need to be comfortable writing or recording entries regularly. Provide clear consent forms and address privacy; participants will be sharing personal details.

In our experience, diversity across user segments yields richer insights. When working with a SaaS platform for small businesses, we recruited freelancers, small‑agency owners and internal IT managers. Their diaries revealed different pain points—one group struggled with pricing transparency, another with integration complexity.

3. Design the diary instrument

Craft prompts that align with your research question. Use a mix of open questions (“What did you try today and how did it feel?”) and structured scales (“Rate how satisfied you felt using feature X on a scale from 1–5”). According to Piasecki et al., electronic diaries can capture rich information when designed thoughtfully. Limit the number of prompts to avoid fatigue; test your diary on a colleague first.

Decide on entry formats. Written text is easiest to analyse; photos add context; short videos can reveal subtle interactions. Provide sample entries to illustrate the expected detail and tone. In one project for an AI‑powered design assistant, we encouraged participants to attach screenshots of confusing error messages. Those images became crucial evidence for prioritising bug fixes.

4. Select tools

Choose tools that make participation easy. Clay lists options like Dscout for rich media, Notion for flexible databases and Google Forms for simple, cost‑effective studies. Ensure notifications remind participants at the right times. Offline support can be important if your target users have intermittent connectivity.

5. Onboard participants

Start with a kickoff session—live or recorded—to explain the study’s purpose and demonstrate how to record entries. Show examples of good and bad entries. Clarify the frequency and types of entries you expect. Maintain engagement through regular check‑ins; a friendly reminder message can boost response rates.

In our projects, we sometimes use a group chat to answer participant questions and share encouragement. Small incentives at milestones (for example, gift cards after week 1 and at completion) help sustain motivation.

6. Run the study

During the study, monitor submissions daily. Send gentle nudges if entries are late, but avoid making participants feel judged. Clay recommends scheduling short touchpoints to answer questions and keep momentum. Be prepared to handle technical issues promptly—if a form link breaks, participants may drop out.

Consider mid‑study interviews. A brief call can clarify ambiguous entries and refresh engagement. For example, in a two‑week diary with an AI chatbot, we discovered from mid‑study interviews that participants were misinterpreting one prompt. We adjusted the phrasing and improved the quality of subsequent entries.

Making sense of diary data

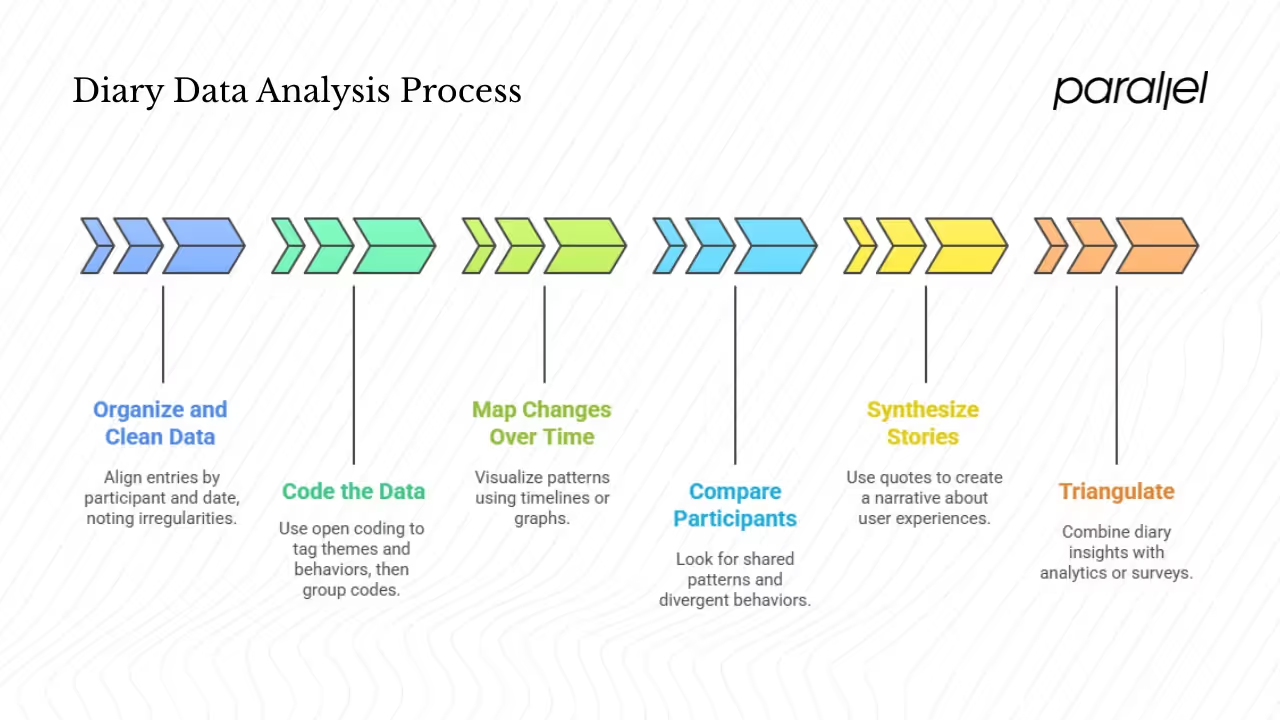

Diary studies produce piles of notes, photos and videos. Without a plan, analysis can be overwhelming. Here’s a practical approach:

- Organise and clean. Align entries by participant and date. Note any missing entries or irregularities. A spreadsheet or qualitative analysis tool (e.g., NVivo, Dedoose, or a simple database) helps manage data.

- Code the data. Use open coding to tag recurring themes, feelings and behaviours. Group similar codes into broader categories—this is known as axial coding. Clay’s article suggests grouping notes by theme, person or time and tagging repeated ideas.

- Map changes over time. Visualise patterns using timelines or graphs. You might track how satisfaction ratings change each week or plot feature usage frequency across participants.

- Compare participants. Look for shared patterns and divergent behaviours. In the AI design assistant study, freelancers and agency owners both struggled with template customisation, but agency owners reported frustration earlier in the process.

- Synthesize stories. Use participants’ quotes to tell a narrative about their journey (but avoid the banned word “journey” by focusing on their experiences over time). This narrative helps stakeholders empathise with users.

- Triangulate. Combine diary insights with analytics or surveys. If diaries indicate that users drop off after a certain feature, check analytics to confirm. Triangulation strengthens conclusions.

Comparing diary study vs other methods:

Common pitfalls and best practices

Diary studies are powerful but they require careful execution. Based on both literature and our own work, here are common challenges and how to address them:

- Participant fatigue. Long studies or frequent prompts lead to drop‑offs. Keep diaries short (2–4 weeks) and prompts concise.

- Missed entries. People forget or get busy. Automated reminders and a designated response window (for example, 24 hours) help. Accept that you’ll have some missing data; plan accordingly.

- Variable data quality. Some entries will be superficial. Offer examples of depth and provide feedback early on. Mixed‑modal prompts (text + photos) can encourage richer responses.

- Privacy concerns. Participants may hesitate to record sensitive information. Clarify how data will be anonymised and who will see it. Allow participants to skip questions or hide details.

- Technical issues. Apps may crash or uploads may fail. Provide offline options (e.g., save notes and upload later) and have a support channel.

- Bias. Participants may report what they think researchers want to hear. Encourage honesty and assure participants there are no right or wrong answers. Use post‑study interviews to probe discrepancies.

McCombie et al.’s 2024 study underscores the importance of centring participant values. They found that participants valued self‑expression, flexibility, non‑judgement, open communication, reflection and meaningful impact. Design your study to honour these values: allow participants to express themselves, listen without judgment and share how their contributions will shape the product.

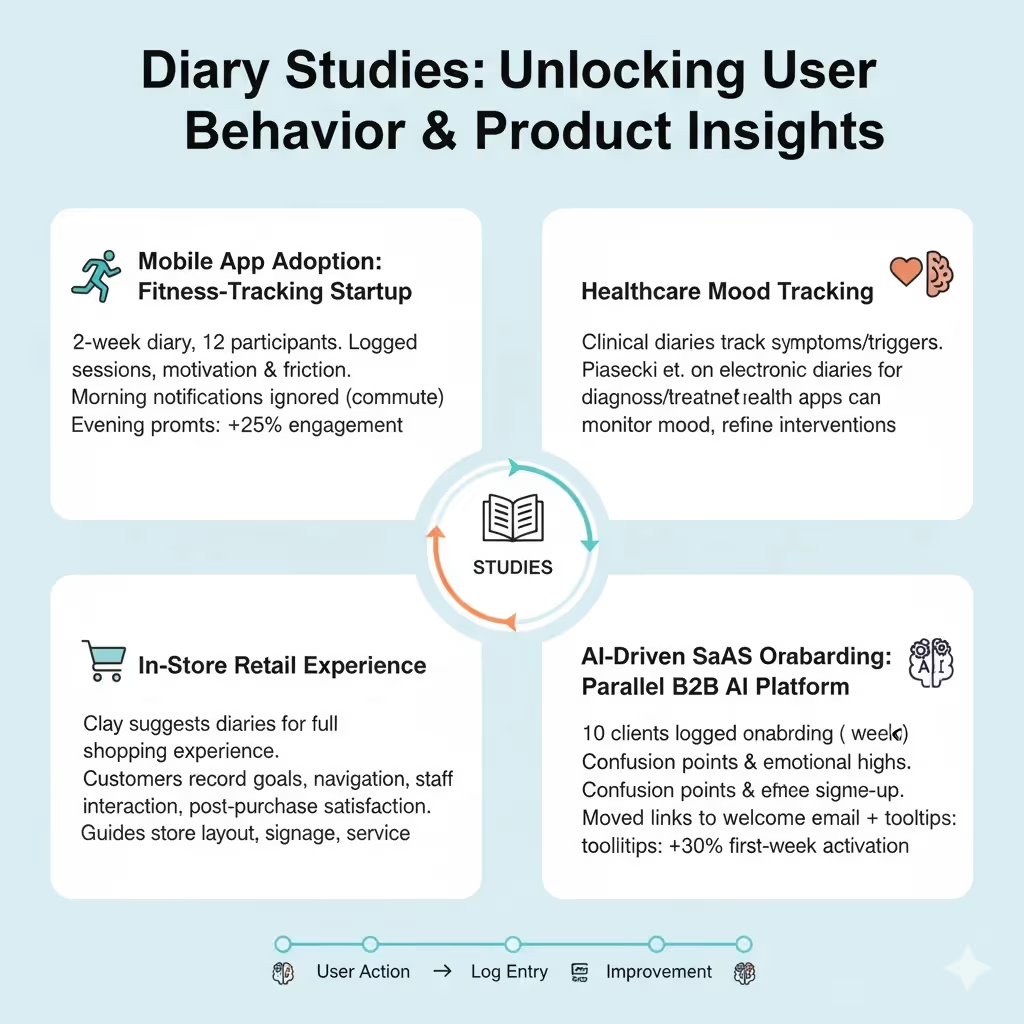

Real‑world examples

Diary studies have been used across domains. Here are a few examples relevant to product teams:

- Mobile app adoption: When we worked with a fitness‑tracking startup, we ran a two‑week diary with 12 participants to understand how people integrated the app into daily life. Participants logged each app session, what motivated them to open it, and any friction. The study revealed that morning notifications were ignored because users were commuting; shifting prompts to evening increased engagement by 25%.

- Healthcare mood tracking: In clinical contexts, diaries track symptoms and triggers. Piasecki et al. describe how electronic diaries can aid diagnosis and treatment planning by gathering day‑to‑day experiences. Startups building mental‑health apps can adopt similar approaches to monitor mood fluctuations and refine interventions.

- In‑store retail experience: Clay suggests diary studies to understand full shopping experiences. Customers record their goals for visiting, navigation ease, interactions with staff and post‑purchase satisfaction. The insights guide improvements in store layout, signage and service.

- AI‑driven SaaS onboarding: At Parallel, we recently helped a B2B AI platform reduce its time‑to‑value by 30%. We recruited 10 clients to log their onboarding steps over two weeks, noting confusion points and emotional highs. Their entries showed that documentation links were often missed because they appeared after the sign‑up confirmation. Moving those links into the welcome email and adding tooltips increased first‑week activation by 30%.

These examples illustrate how diaries uncover micro‑moments and trends that other methods miss. They also show that diaries can support decisions at every stage—from initial concept testing to post‑launch refinement.

When not to use a diary study

Diary studies aren’t a universal fix. Avoid them when:

- You only need a snapshot. A short survey or usability test may suffice for single‑session feedback.

- Direct observation is possible. If you can watch users interact with your product (e.g., in a usability lab or through remote observation tools), you may not need diaries.

- Sensitivity is high. If the topic involves very sensitive data (e.g., personal health or financial details), participants may be reluctant to record entries, even with anonymisation.

- The time window is too long. Long studies can lead to attrition and poor data. Consider break‑up interviews or analytics instead.

- You need quantitative precision. For highly structured, quantitative measurement, sensors or usage logs may provide more reliable data.

Use judgement: diaries are best when you need longitudinal, contextual, qualitative insight—especially for early‑stage products.

Closing thoughts

Diary studies ask participants to narrate their experiences over time. They are resource‑efficient compared with constant field observation, yet they provide deeper context than surveys or analytics. The 2007 review by Piasecki and colleagues emphasises that electronic diaries offer rich information for diagnosis and treatment when designed carefully. Recent research on digital diaries in mental health underscores the importance of centring participant values. Clay’s 2024 guide shows how to adapt diaries for product design and lists practical tools.

For founders and product leaders, diary studies can be a powerful compass. They reveal not just what users do but why they do it, how they feel along the way and how those feelings change over time. Done well, diaries help you make thoughtful, user‑centred decisions, reduce time‑to‑value and build products that fit into real lives. Start small, stay curious, and let your participants tell you the story of their experience.

Frequently asked questions

1) What is the purpose of a diary study?

A diary study collects rich, temporal, contextual self‑report data about behaviours, emotions and experiences over time. It reveals patterns and shifts that one‑off methods miss. As Bolger et al. describe, diary methods capture particulars of daily life that other designs cannot.

2) What is the format of a diary study?

A diary can take many forms: text entries, short scales, photos, voice notes or videos. Clay notes that diaries can be open, closed or mixed; digital diaries use apps or web forms, while paper diaries remain viable. Event‑based and time‑based prompts are both possible. Choose a format that suits your research goals and participants.

3) What is an example of a diary study?

Imagine a startup releasing a habit‑tracking app. For two weeks, participants record every time they open the app, why they opened it, what they did and how it felt. Researchers then map patterns across days, identifying friction points and emotional peaks. Another example is a retail diary where shoppers document each step of an in‑store visit.

4) How do I set up a diary study?

Steps include defining research questions, recruiting committed participants, designing prompts and selecting tools, onboarding participants with clear instructions, running the study with regular check‑ins and incentives, and finally analysing and synthesising the data. The earlier sections of this guide expand on each step.

.avif)