What Does Closed Beta Mean? Guide (2026)

Learn the meaning of closed beta, how it differs from open beta, and why companies invite select users to test products before launch.

You’ve just polished a new feature and want to put it in front of real people, but you aren’t ready to throw the doors open. A closed beta offers a controlled way to do just that. In its simplest sense, it’s a testing phase where access is restricted to a small, selected group of users.

This article addresses the question what does closed beta mean for founders, product leads and design or engineering teams who want to reduce risk and improve their product before a wider launch.

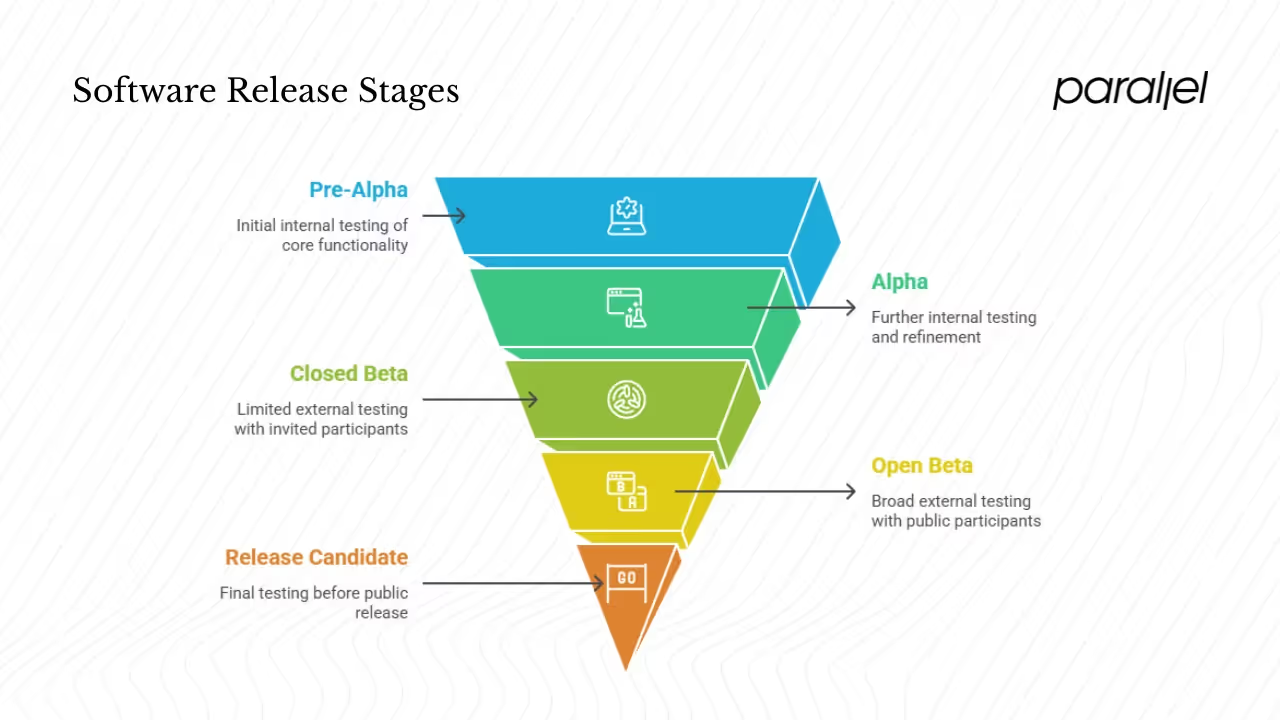

Where beta fits in the release cycle

Modern software and games pass through several stages on their way to a public release. During pre‑alpha and alpha stages, developers build and test the core functionality internally. The beta phase marks the point when external participants start using the product. James Stanier points out that open betas allow “normal people” to get involved, while closed betas are invite‑only and used to control user numbers. After beta comes a release candidate and eventually general availability, but the beta stage is the first chance to learn how the product behaves under a range of conditions.

What does closed beta mean in this context? Unlike internal testing, a closed beta invites a limited group of external participants to use the product under real‑world conditions. The aim is to reveal bugs that appear only in varied environments and to understand how users interact with features such as onboarding, navigation and performance. Because it sits between internal development and open release, a closed beta provides a bridge between theory and reality, giving teams the chance to course‑correct without being exposed to the entire market.

Some teams offer early access or previews as alternatives. Early access programmes allow anyone to pay to play an unfinished game, while a closed beta remains restricted by confidentiality. The choice depends on whether you need scale or control.

Understanding the closed beta

So, what does closed beta mean in practical terms? Nitor Infotech describes a closed beta version as one that is available only to invited participants. Global App Testing echoes this by defining it as releasing software to a select group whose number is limited and chosen carefully. Adjust’s glossary likens it to a private dinner party rather than an open invitation. In other words, it’s a private test that sits between internal alpha and public beta.

So, what does closed beta mean in practical terms? At its core it refers to a private test available only to invited participants.Global App Testing emphasises that the group is carefully chosen and small, and Adjust describes it as a private dinner party rather than an open invitationadjust.com. In other words, a closed beta sits between internal alpha and public release and invites a handful of trusted users.

Access is usually granted through sign‑ups, applications or referral programmes. Games may issue access codes; companies may invite loyal customers. Participants often sign confidentiality agreements, and access can be limited by region or platform. In some cases, accounts are wiped after the beta ends, as Riot did with Valorant. Testers should expect bugs and incomplete features and be ready to provide feedback. This controlled environment fosters collaboration and rapid improvement.

When designing your own programme, think about who you want involved and how you will onboard them. Clear communication about expectations, feedback channels and the purpose of the test helps participants feel valued and reduces frustration. Understanding these basics reinforces what closed beta means for both organisers and testers.

Benefits and trade‑offs

The main advantage of a closed beta is control. By limiting who participates, teams can better manage feedback, support, and infrastructure. This setup helps produce focused, high-quality insights.

Nitor identifies several benefits of this approach:

- Real-world feedback that reflects how people actually use the product

- Bug discovery before launch

- Usability insights that guide improvements

- Performance evaluation under realistic conditions

Inviting specific groups—like heavy users, domain experts, or influential customers—also helps test assumptions about user behaviour and product-market fit.

The Financial Perspective

There’s also a cost-saving angle. Research from Perforce indicates that fixing defects during testing costs about 15 times more than fixing them during the design phase. Catching issues early through a closed beta can significantly cut long-term costs.

On top of that, exclusivity has marketing value. Being part of a select group can make testers feel invested and spark early buzz.

The Trade-offs

Closed betas aren’t without downsides:

- A smaller tester pool means fewer edge cases are covered.

- If testers don’t reflect your target users, feedback can be skewed.

- Teams face extra work managing invitations, access codes, and support.

- Testers might expect stability and grow frustrated if the product crashes.

- Leaks can still happen despite non-disclosure agreements.

Nitor also points to challenges like limited control over testing environments and incomplete coverage. These drawbacks need to be considered when choosing between a closed or open beta.

When a Closed Beta Makes Sense

Closed betas work best for:

- Early-stage products

- Complex systems

- Projects where public failure would be costly

If the goal is to stress test servers or collect large-scale usage data, an open beta or early access program may be the better route. A common strategy is to start with a closed beta to fix major issues, then gradually move into an open beta as confidence grows.

Variants of closed beta programmes

Closed betas come in several flavours. Some focus on technical or compatibility issues and invite experienced testers. Others expose only a subset of features, target influencers or long‑time customers, or gradually add more participants to manage server load. Region‑based soft launches test monetisation and retention in specific markets before going global, and hybrid programmes may start private and then transition to open access.

How long should a closed beta run?

There is no universal duration, but the test should last long enough to collect meaningful feedback and iterate. Adjust’s glossary suggests that many beta tests run three to five weeks. Smaller SaaS teams may run closed betas for one to three months, while large games may continue until server stability and gameplay balance meet targets. What matters is to define exit criteria: metrics for crash rates, retention or user satisfaction, and thresholds for bug counts. Running a beta for too long can cause tester fatigue, while ending it too soon may leave critical issues undiscovered. Plan milestones for reviewing feedback and decide upfront what signals will prompt a transition to the next stage.

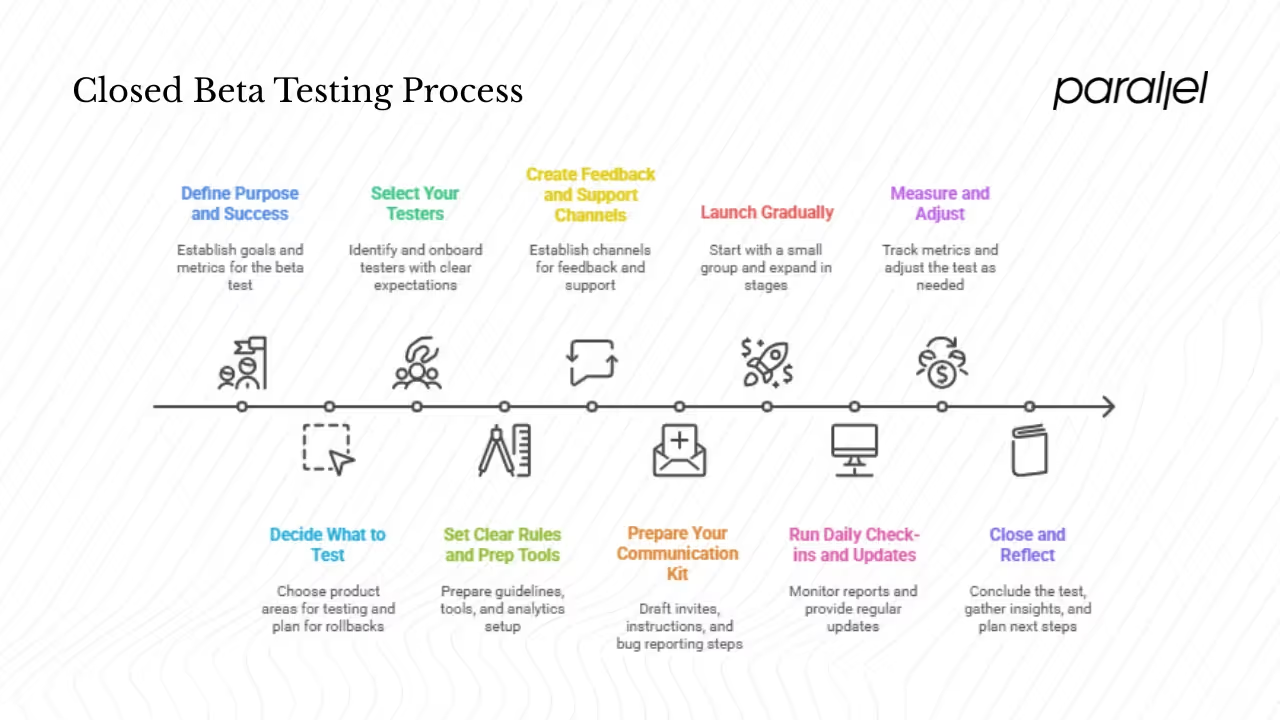

Running a closed beta: a step‑by‑step plan

1. Define purpose and success

Start by answering what closed beta means for your product. List your main learning goals, such as testing a new feature, checking scalability, or validating onboarding. Pick the numbers that matter: crash rate, task completion, or performance.

2. Decide what to test

Choose which parts of the product to expose and which to hold back. Mark any risky or unstable areas, and set up a rollback plan so you can revert quickly if something breaks.

3. Select your testers

Identify who should join—paying customers, early adopters, or subject experts. Make sure they understand what closed beta means for them: limited access, experimental builds, and an expectation to give feedback.

4. Set clear rules and prep tools

Prepare NDAs or usage guidelines, explain how you’ll handle their data, and configure analytics and crash tracking. Build a dashboard for your important numbers.

5. Create feedback and support channels

Set up one central place for bugs and another for short surveys or feature input. Define how fast you’ll respond to serious issues and who’s responsible for each part.

6. Prepare your communication kit

Draft invites, install instructions, and quick “how to report bugs” steps. Include a short explanation of what closed beta means in every message. Keep a list of known issues to manage expectations.

7. Launch gradually

Start small with internal users or a handful of trusted testers. Fix any blockers, then add more participants in stages. After each wave, review metrics and feedback before expanding.

8. Run daily check-ins and updates

Triage reports every morning, release small fixes often, and share updates so testers know you’re listening. Keep the feedback cycle short and transparent.

9. Measure and adjust

Track your chosen metrics closely. If key numbers improve, grow the test group; if they worsen, pause and fix before scaling. That’s the essence of what closed beta means: learning through controlled exposure.

10. Close and reflect

Set an end date or condition, communicate what happens next (data wipes, account carry-over, or next phase), and gather insights. Thank participants and summarise what worked, what didn’t, and how the results will shape the full release.

Examples and lessons

Real‑world cases shed light on what closed beta means. The Valorant beta in 2020 shows how controlled access can build excitement while avoiding server overload. Riot required players to link accounts and watch streams for a chance at access, limited numbers to keep the game stable and reset progress at the end. This allowed them to stress‑test infrastructure and refine gameplay before the full launch.

In our work at Parallel, a voice‑assistant project invited a handful of domain experts to uncover issues with background noise, and a no‑code platform used a private beta to streamline onboarding and cut time‑to‑first‑use by 30%. These experiences show how closed betas surface issues early and allow targeted iteration.

Some projects, such as Riot’s 2XKO, move from private tests to early access programmes. Understanding when to transition helps teams decide whether to stay closed or broaden participation.

Best practices and common pitfalls

From research and experience, several guidelines become clear:

- Select a representative group. Avoid inviting only power users or insiders. Aim for a mix of skill levels, locations and use cases to surface a wider range of issues.

- Keep the scope narrow. Resist the temptation to test every feature. Focus on a few areas to ensure you can act on feedback quickly.

- Be transparent. Let participants know what state the product is in, what is expected of them and how their data will be handled. Adjust emphasises completing legal and compliance checks before inviting testers.

- Centralise feedback. Use a single channel—such as a forum or survey—for bug reports and suggestions. This makes it easier to track and prioritise.

- Provide support but manage expectations. Set up dedicated support but make it clear that the product is unfinished. Encourage testers to report issues without expecting immediate resolution.

- Protect sensitive information. Use confidentiality agreements and restrict access to sensitive data. Centercode states that closed tests often rely on NDAs.

- Plan for scale. If the beta is successful, be prepared to invite more participants or transition to an open beta. Ensure that infrastructure and support channels can handle increased load.

- Approach it as an experiment. Set hypotheses, measure outcomes and be willing to adjust your product and process. A closed beta is an opportunity to learn, not just a marketing event.

Conclusion

A closed beta is more than a procedural step; it’s a strategic tool for learning and risk management. It’s an invite-only phase where a limited group provides real‑world feedback under controlled conditions, helping you catch issues and refine the product before a wider release. Smaller tester pools and added overhead are trade‑offs, but the benefits often outweigh them. Approach your beta with clear goals, measure what matters and use insights to shape a stronger launch.

Frequently asked questions

1) What is the difference between open beta and closed beta?

Anyone can join an open beta, while a closed beta is invited‑only and usually backed by confidentiality agreements.

2) How long does a closed beta last?

Many run for three to five weeks, though the exact duration depends on product complexity and feedback goals.

3) Why run a closed beta?

It lets teams catch bugs, test performance and gather early feedback in a controlled environment, reducing risk before a wider release.

4) Who can join a closed beta?

Participants are selected through invitations, applications or access codes, based on criteria such as usage patterns or expertise.

5) Do testers keep their progress or data?

In some game betas, accounts and progress are wiped—for example, Riot reset ranks and refunded purchases after Valorant—while software products may migrate data. The policy should be stated upfront.

6) Can testers share feedback or screenshots publicly?

Often not. Most private tests require confidentiality agreements, though some permit limited sharing if specified.

7) What happens after a closed beta ends?

Teams analyse feedback, fix issues and decide whether to move to open testing, early access or a full release. The beta is a learning stage, not the end of development.

.avif)