What Is an Epic in Agile? Guide (2026)

Learn about epics in agile methodology, how they structure large user stories, and how to break them into manageable tasks.

When you’re building a product from scratch, a messy backlog and scattered plans slow your team down. I’ve watched founders and product managers drown in tickets without a clear sense of where they’re headed. An epic can bring order to the chaos. The question what is epic in agile matters because it helps you connect big goals with everyday work and reclaim momentum.

Epics give structure when a feature is too large for one sprint. They help teams deliver value in phases while keeping everyone pulling in the same direction. In this article I’ll explain what epics are, how they fit into the product hierarchy, and why they’re invaluable for early‑stage startups. I’ll share lessons from our work with emerging product teams and examples from leading product organizations.

What is an epic in agile?

An epic is simply a large user story that’s too big to complete in a single iteration. Mike Cohn, who helped popularise user stories, notes that epic is a label we apply to a large story and there’s no magic threshold at which a story becomes an epic. In other words, it’s a big story that requires splitting. TechTarget describes an epic as a large body of related work items completed over multiple sprints; it’s broken down into user stories that show how the goal will be met. BusinessMap echoes this definition: epics are large pieces of work that can be broken down into smaller, more manageable work items, tasks, or user stories that share the same goal. Nimblework adds that epics represent high‑level requirements or features that are too large to finish in a single sprint and may require collaboration across multiple teams or departments.

Why does this matter? Because without an epic, you have either a vague aspiration or a never‑ending list of small tasks. The epic connects big‑picture objectives with the granular work that delivers them. It lives in the product backlog and helps you visualise progress toward a meaningful goal. When people ask what is epic in agile they’re really asking how to manage the gap between strategy and execution.

Epic vs. story vs. theme: where does an epic fit?

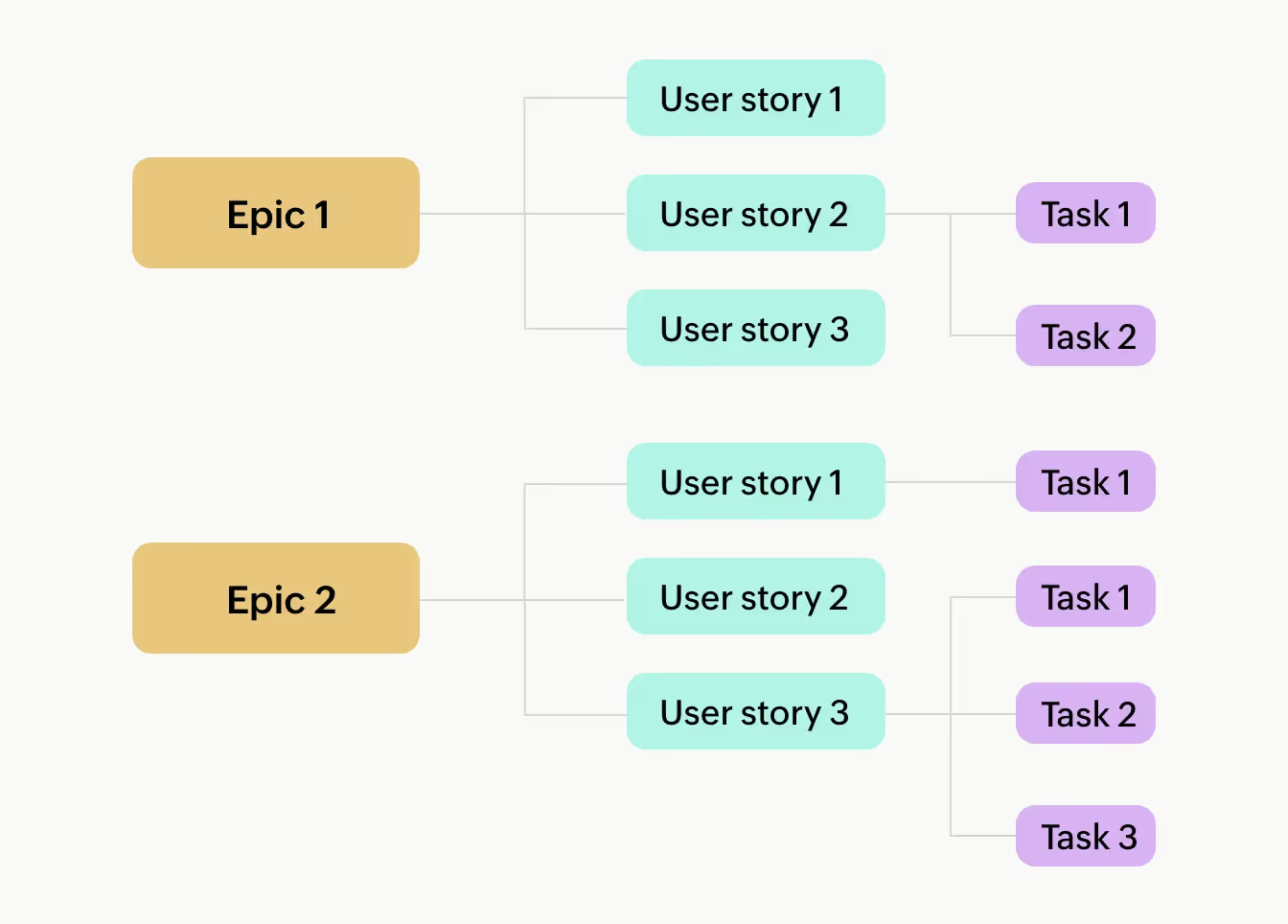

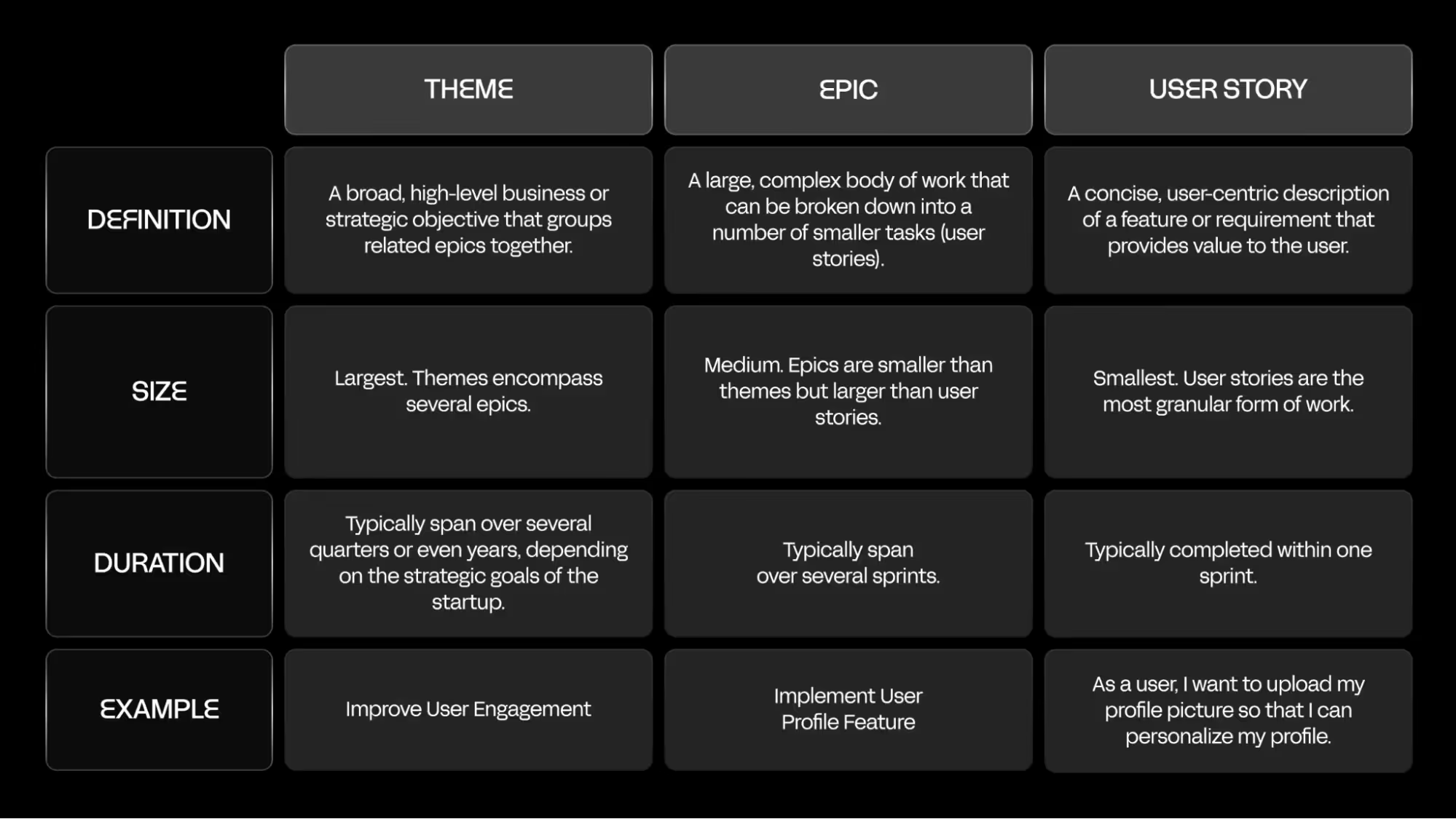

Agile frameworks use a hierarchy to keep work organised:

- Theme — A broad strategic objective that guides product direction. Themes sit at the top of the hierarchy and group related epics. Productboard points out that themes provide context for decision‑making and drive the creation of epics.

- Epic — A collection of tasks or user stories that support a theme. Epics break down development work into shippable components while keeping the daily work connected to the larger objective. Because an epic is too large for one sprint, it needs to be split into smaller stories.

- User story — The smallest unit of work, usually written from the end user’s perspective. TechTarget describes user stories as the requirements that development teams create units of software from; they are meant to be completed within a sprint.

- Task — The individual actions developers take to deliver a user story. Nimblework explains that tasks are the most granular unit of work and represent the specific actions needed to fulfil a user story.

By grouping stories under epics and epics under themes, you maintain clarity at different levels of abstraction. The hierarchy prevents large goals from being lost in the weeds of day‑to‑day tasks. When I get asked what is epic in agile, I point to this hierarchy – it’s simply the bridge between strategy and execution.

A quick analogy

Imagine you’re planning a road trip. The theme is the overall destination, like “Visit all national parks in the South.” Each epic could be a park you plan to visit, such as “XYZ Tiger Reserve.” Within each epic, stories describe specific activities, like “Book safari tickets” or “Pack binoculars.” Tasks might include “Write an email to the park” or “Check camera batteries.” The structure helps you stay on track without forgetting the broader purpose.

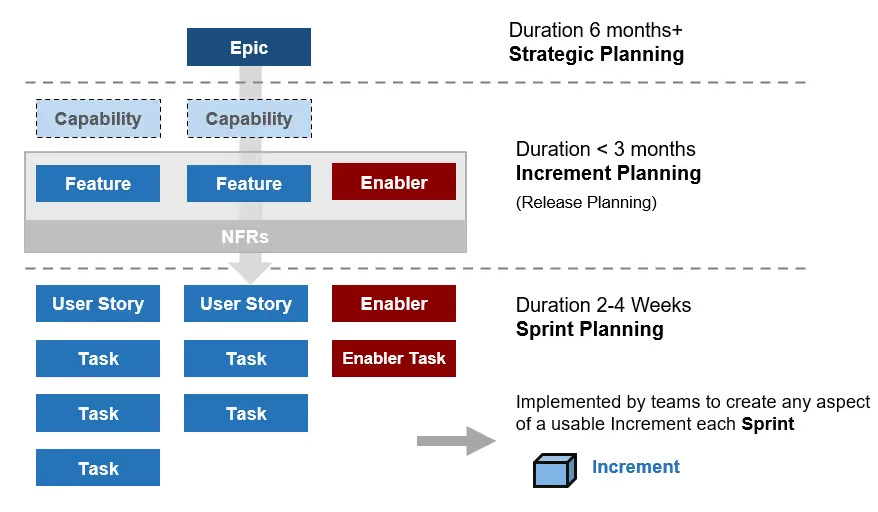

Epic vs. sprint: scope vs. time

A sprint is a fixed time‑box, usually one to four weeks, during which a team commits to delivering a set of stories. An epic isn’t tied to a timeframe; it’s defined by scope. Monday.com emphasises that epics connect miniature tasks to overarching goals and can be regularly updated based on feedback. TechTarget notes that epics usually span more than one sprint and might be spread across multiple teams. For early‑stage startups, this distinction is crucial: don’t try to cram an epic into a sprint. Slice the epic into stories first, assign those stories to sprints, and keep the epic visible across iterations.

I’ve seen teams view an epic like a mini‑project with a fixed deadline. That mindset causes stress and hides progress. Instead, view the epic as a living container. It changes as new insights come up. Ask yourself what is epic in agile and you’ll realise it’s a planning tool, not a calendar entry.

Why epics matter for startups

Startups often juggle feature roadmaps, technology modules, and business goals with limited resources. Epics bring structure and a sense of unity. Here’s why they are so valuable:

- Visibility of big goals: Monday.com explains that working in short sprints makes it easy to lose sight of the bigger picture; epics ensure tasks stay connected to project goals. When you run lean, seeing progress toward a meaningful objective keeps morale high.

- Link between business and tech: BusinessMap says epics should be specific and measurable so managers can track them and ensure they contribute to greater strategic objectives. This connection bridges the gap between business outcomes and software work.

- Structure for complex features: Productboard notes that epics break down development work into shippable components while keeping it tied to a theme. For example, building a marketplace or integrating a CRM demands coordination across design, engineering, and marketing; epics provide that umbrella.

- Bringing teams together: TechTarget observes that product owners use epics to organise product backlog items and provide a structure through which to manage the backlog. When your company has multiple squads, epics connect their efforts toward the same business goal.

From my experience working with machine‑learning and SaaS startups, epics also promote healthy conversations. When you create an epic, you force stakeholders to articulate why something matters. This discussion often surfaces hidden assumptions and ensures everyone pulls in the same direction. When someone on your team asks what is epic in agile, they’re implicitly asking how to keep the vision clear while moving fast.

How to write a good epic

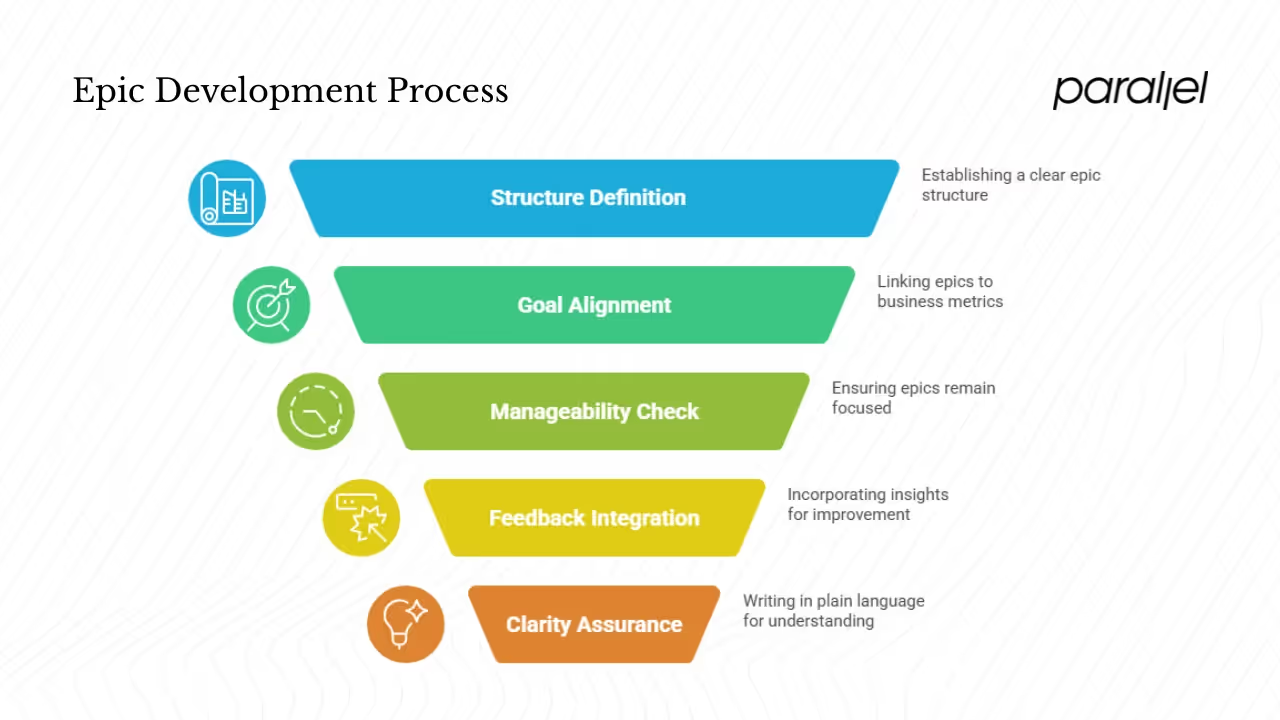

Writing an epic draws on both skill and craft. You need to capture the why, the what, and enough detail for teams to plan, without turning it into a specification document. Here are some guidelines drawn from Productboard and our own practice:

- Involve stakeholders early: A well‑written epic is a shared understanding. Productboard advises collaborating with engineering and design teams when writing the epic so that everyone understands the goal. Involve product managers, engineers, designers, and customer success early to surface different perspectives.

- Follow a simple structure: Bindiya Thakkar suggests a four‑section structure: (1) Introduction that covers the why and what; (2) Product requirement describing what needs to be built; (3) Technical requirement; (4) Design requirement. I like to add a fifth section for Measurable outcome so you can track impact.

- Link to business goals: Epics aren’t just engineering tasks. They exist because they move a business metric. Productboard encourages selecting a metric for the epic and tracking improvement. If you can’t articulate the desired outcome, you shouldn’t be writing an epic.

- Keep it manageable: An epic should not be so long that it becomes another product in itself. Productboard notes that two weeks is often a good length for an epic. In my work I’ve found that keeping epics under a month helps maintain focus without losing flexibility.

- Invite feedback loops: Monday.com suggests connecting epics with OKRs and integrating customer feedback loops. Define how you’ll collect insights (surveys, user interviews, analytics) and revisit the epic regularly.

- Write in plain language: Avoid technical jargon unless necessary. Use active voice and make sure someone outside your team can understand the goal. When new hires ask what is epic in agile, they should be able to read your epic and get it.

Four‑section template

To make this concrete, here’s a simple template we use at Parallel when crafting epics:

- Introduction: Context and purpose. Why are we doing this? What problem does it solve? How will it support a business goal?

- Product requirement: Describe the functionality from the user’s perspective. Keep it broad; the details belong to stories.

- Technical requirement: Outline technical constraints, dependencies, or integrations. Call out known risks and unknowns.

- Product requirement: Describe the functionality from the user’s perspective. Keep it broad; the details belong to stories.

- Design requirement: Specify any critical design considerations, such as accessibility requirements, interaction patterns, or branding guidelines.

This structure keeps the epic clear yet flexible. It ensures we don’t drown stakeholders in detail while giving our engineers and designers enough to start planning. When you can answer this question using this template, you’re ready to break it down into stories.

Practical examples

Productboard: pivoting a travel agency to experiences

Productboard offers a useful scenario for illustrating the theme→epic→story hierarchy. Imagine you’re a senior product manager at a web‑based travel agency whose bookings have dropped by 30%. After discussions, you decide to pivot into experiences. The theme becomes Transition from a traditional accommodation agency to a complete web‑based provider of experiences and activities.

To support this theme, you define several epics:

- Launch a web marketplace for experience providers and end‑users.

- Create an onboarding program for experience providers.

- Expand the current booking system to support experiences and activities.

- Build a mobile app to attract a younger audience of experience buyers.

Each epic is still too large to deliver in one sprint. So you break them down into stories. For instance, the marketplace epic might include stories like developing the signup process for providers, designing an experience page, reducing loading times in search, and writing a launch newsletter. These stories are then allocated to specific teams. This example shows how epics keep the vision focused while enabling parallel progress.

BusinessMap: integrating a CRM system

BusinessMap illustrates another scenario. Imagine company A delivers web‑hosting services and wants to address support requests efficiently by integrating a third‑party CRM. The initiative is Incorporate an enterprise CRM system to address customer requests. Supporting this initiative are epics such as Select a CRM platform and Implement the CRM system. The epic Select a CRM platform might include user stories like “As a project leader, I need to collect business requirements and technical specifications so that we can choose a CRM solution to address customer inquiries faster*.

Similarly, company B might set a goal to penetrate the project management software market. An epic could be Develop a budget management feature in the PM software, with user stories about recording spending information on projects. These examples show how epics act as containers for delivering strategic initiatives through smaller, testable increments.

Tracking epics effectively

Tracking is where many teams stumble. An epic isn’t finished until all its stories are done, and that can span multiple sprints. Here are some tracking practices drawn from research and our work:

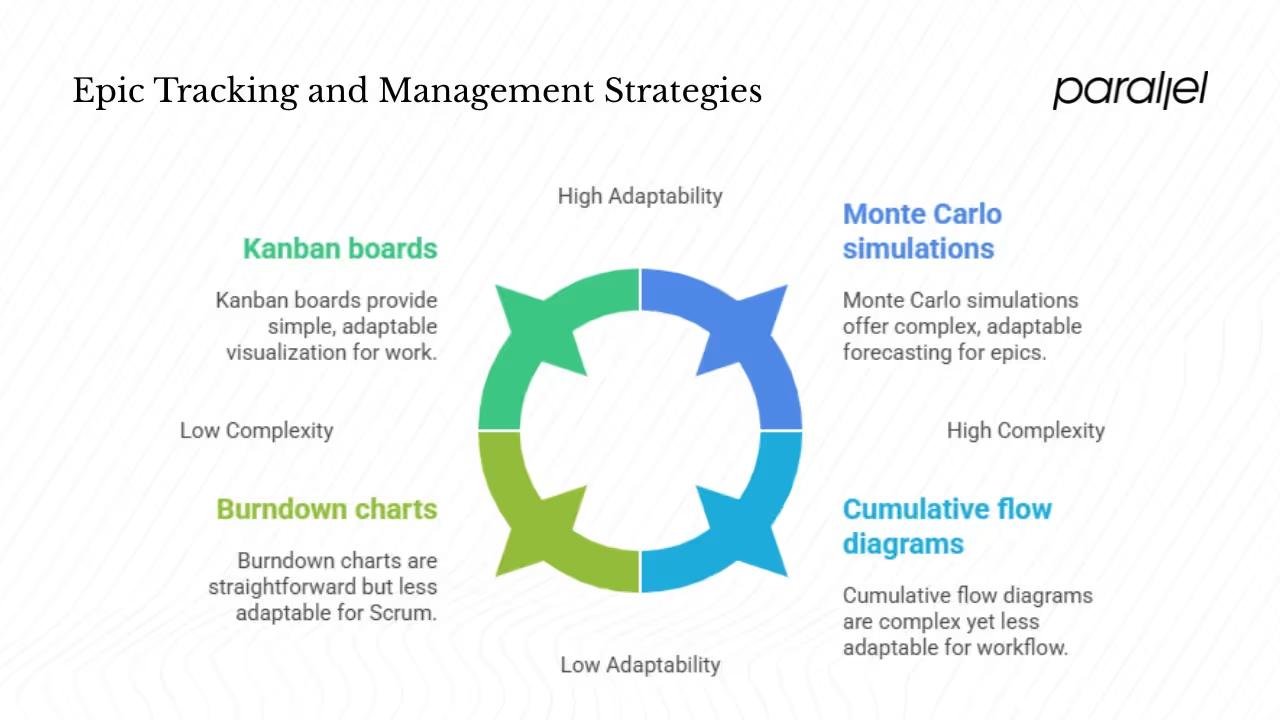

- Visualise work with Kanban boards: BusinessMap suggests mapping epics and their user stories on a Kanban board to provide transparency and help teams pull work when ready. Visualising progress ensures nothing slips through the cracks.

- Use burndown charts for Scrum teams: BusinessMap notes that Scrum teams often use burndown charts to monitor how much work remains in an epic and estimate how many sprints are needed.

- Use cumulative flow diagrams and Monte Carlo simulations for Kanban: Cumulative flow diagrams help monitor workflow stability and reveal bottlenecks. Monte Carlo simulations provide probabilistic forecasts about when an epic might finish by using historical throughput data.

- Set measurable outcomes: Productboard emphasises selecting a metric for each epic and tracking improvement to keep stakeholders informed and teams motivated. For example, measure adoption rates, conversion rates, or response times.

- Adapt scope as feedback comes in: Monday.com stresses flexibility and adaptability; as priorities change or new information arises, you can adjust or re‑prioritise epics. Use feedback loops to reshape the epic without losing sight of the goal.

In our own projects, we set up a simple dashboard for each epic. It shows the list of stories, their current status, and the metric we’re tracking. We review this dashboard weekly. If we discover a story is stuck, we unblock it quickly. If the metric isn’t trending in the right direction, we revisit the epic’s definition. This practice ensures we always know how our epics are performing and keeps the team moving together toward the bigger objective. When the team asks what is epic in agile during a retrospective, this dashboard offers an immediate, visual answer.

Common pitfalls to watch for

With all their benefits, epics can also be misused. Here are some pitfalls I’ve observed:

- Not splitting the epic: Teams sometimes view an epic like a mini project and avoid breaking it into stories. This delays feedback and hides complexity. Mike Cohn warns that calling a story an epic signals it’s too big to bring directly into a sprint. Always split the epic before planning.

- Over‑engineering terminology: Agile vocabulary can become a trap. People argue about whether something is a feature, epic, or story. Cohn reminds us that these terms are just labels; their definitions are flexible and not crucial to success. Don’t let the tool dictate your thinking.

- Viewing an epic like a time‑boxed sprint: An epic is based on scope, not time. Trying to squeeze an epic into a fixed period defeats its purpose and leads to rushed work. Define a manageable scope, slice it into stories, and let it span multiple sprints.

- Neglecting cross‑team collaboration: Epics often involve multiple disciplines. Failing to involve design or engineering early leads to out‑of‑sync expectations. Productboard advises involving the whole team when writing the epic.

- Ignoring metrics: Without a metric, you can’t tell whether the epic delivered value. Select a measurable outcome and track it consistently..

- Using tooling as a crutch: JIRA and other tools enforce strict hierarchies that may not fit your organisation. Focus on the conversation and shared understanding rather than the ticket structure. The tool should support your thinking, not drive it.

Conclusion

Put simply, an epic is just a large user story that drives a business goal and spans multiple sprints. It sits between themes and user stories, providing structure without imposing rigid timelines. By answering what is epic in agile, early‑stage startups gain a way to connect strategy to execution, bring product, design, and engineering efforts together, and measure progress.

Epics matter because they keep big goals visible without letting them get lost in granular tasks. They allow you to organise complex features or modules as backlog items, bridge business goals with development phases, and support agile planning with clear phases and measurable outcomes. Done well, epics help you deliver value in increments and adjust based on feedback.

Next time you find yourself overwhelmed by a long list of tickets, step back. Identify your next initiative, craft an epic using the four‑section structure, and break it into stories. Track it visibly, adjust as you learn, and stay focused on the outcome. When someone on your team wonders about epics, you’ll have a clear answer and a practical path forward.

Frequently asked questions

1) What is a story vs. an epic?

A user story is the smallest unit of work that delivers user value within a sprint. A story describes a feature from the user’s perspective and is meant to be completed in a single iteration. An epic is a larger requirement that needs to be broken down into multiple stories. It spans more than one sprint and supports a broader objective. TechTarget points out that epics are large bodies of related work items completed over multiple sprints and are broken down into lists of user stories that show how the goal will be met.

2) What is an epic vs. a sprint?

A sprint is a time‑boxed development cycle, usually one to four weeks. An epic is based on scope and spans across sprints. Monday.com emphasises that epics keep tasks connected to project goals and can be updated as feedback comes in, whereas sprints are fixed time periods.

3) What is theme and epic in agile?

A theme is a broad strategic objective that groups related epics. Epics sit below themes and group user stories that contribute to that strategy. Productboard explains that themes provide context and drive the creation of epics, while epics break down development work into shippable components.

4) What is the simple definition of epic?

In plain terms, an epic is a large user story that’s too big for one sprint. Mountain Goat Software defines an epic as a large story with no magic threshold; it’s simply a label applied to a story that’s too big to bring directly into a sprint. BusinessMap and others echo this view, emphasising that epics are large pieces of work broken down into smaller tasks or stories sharing the same goal.

.avif)