What Is an Epic in Product Management? Guide (2026)

Learn what an epic means in product management, how it helps structure large work items, and how to break it down for agile teams.

Stop for a second and look at your backlog. It might contain dozens of tickets: bug fixes, feature ideas, user stories. Without a structure, you risk losing focus. Early‑stage teams I coach often ask me what is an epic in product management and why they should care. An epic is the missing organising element between your vision and your day‑to‑day tasks. It groups related stories under a shared outcome, enabling better planning, cross‑team coordination and meaningful progress. In this guide I’ll explain what epics are, how they fit into Agile and product hierarchies, how to write and plan them, and common pitfalls to avoid.

What is an epic in product management?

You can’t use epics effectively until you understand what they represent. Atlassian defines an epic as “a defined body of work that is segmented into specific tasks (called ‘stories’ or ‘user stories’) based on the needs/requests of customers or end‑users”. The Nielsen Norman Group adds that an epic is a “large user story that the development team divides into smaller stories and tasks to complete over time and across multiple sprints”. The CPO Club echoes this, describing an epic as a collection of smaller user stories that describe a large work item. In other words, when people ask me what is an epic in product management, I say: it’s a container for related stories that deliver a chunk of customer value too big for a single sprint.

An epic sits between high‑level strategic themes and the granular user stories your teams work on. It’s larger than a feature, spans multiple sprints, and has a clear business outcome. There’s no strict size limit; what one startup calls an epic might be a feature in a larger enterprise. The defining characteristics are scope and intent:

- Outcome driven: A good epic defines a measurable outcome, such as “reduce onboarding abandonment by 20%.” Without a clear objective, it becomes a dumping ground.

- Decomposable: Epics can be divided into independent stories that each deliver value.

- Time bounded: Epics should complete within a release cycle. If they run indefinitely, break them into smaller epics.

- Flexible scope: As you learn, you can add or remove stories; epics are living artefacts.

Understanding these basics prevents you from using epics as catch‑all labels. Instead, they become purposeful structures that align work to strategy.

Grasping what is an epic in product management sets the foundation for the hierarchy we discuss next.

How epics fit into Agile and product hierarchies

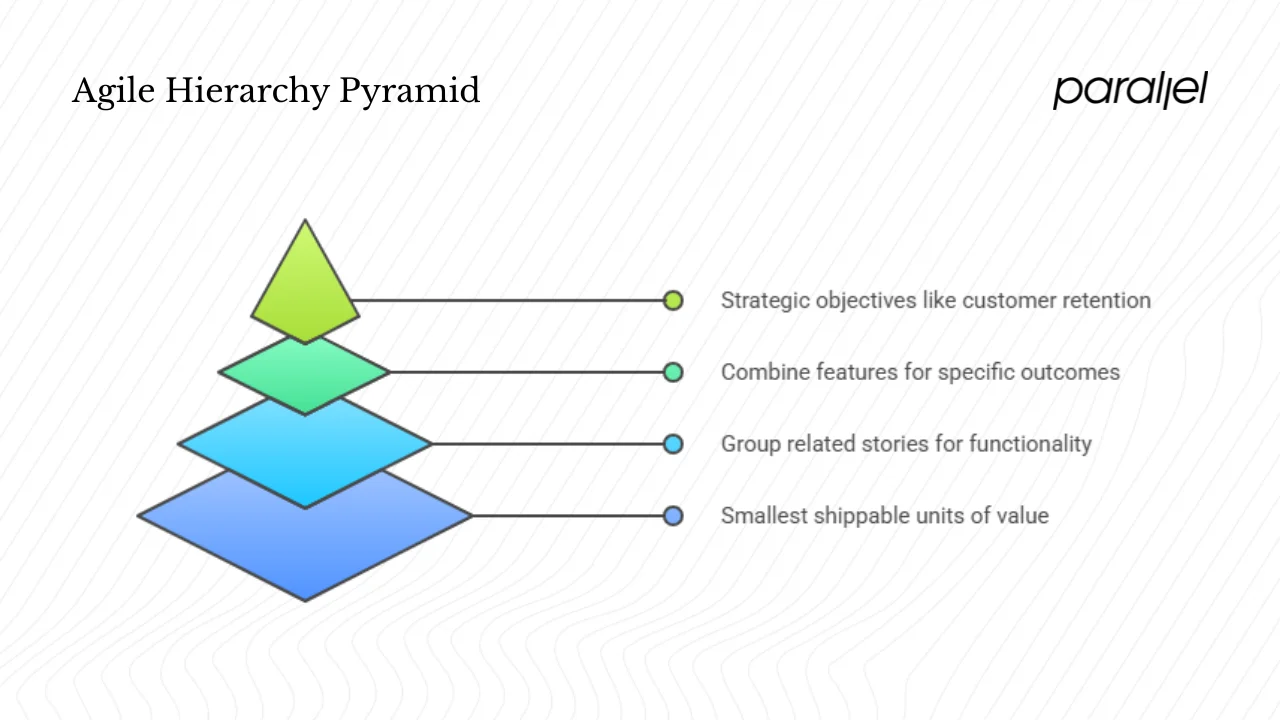

Once you understand the concept, the next question is how epics relate to stories, features and themes. Here’s the hierarchy many teams use:

- User stories are the smallest, shippable units of value. They follow the familiar format, “As a [user], I want [goal] so that [benefit].”

- Features group related stories that implement a single functionality. Not every team uses this layer; early‑stage teams often jump straight from epics to stories.

- Epics combine several features or story clusters that work toward a specific outcome. The CPO Club notes that epics “contain several user stories and each user story in turn contains all the tasks required for implementation”.

- Themes or initiatives sit above epics and represent strategic objectives like “Improve customer retention” or “Enable self‑serve onboarding.”

Understanding the hierarchy helps you decide when to use an epic versus a story or theme. For example, in the theme “Improve activation,” you might have an epic called “First‑time user flow redesign” and another epic called “Onboarding email series.” Each epic breaks down into several stories.

Epics also integrate with Agile planning tools. They live in your backlog above stories and help you organise and prioritise. Many organisations tie business metrics to epics. The 17th State of Agile report found that one‑third of respondents use OKRs linked to epics to measure success. It also notes that epic and release burndown charts are among the top metrics used to evaluate team performance. These statistics underscore the importance of epics in connecting work to outcomes.

Epics also encourage cross‑functional collaboration because multiple teams can work on stories under the same epic. Atlassian points out that epics help teams break work into shippable pieces so that large projects actually get done and teams continue to ship value to customers on a regular basis. In early‑stage companies, grouping tasks this way fosters accountability, gives designers, engineers and marketers a shared target, and reduces the churn that comes from tackling isolated tickets without a common goal.

Examples: Bringing epics to life

To truly grasp the idea, examples help. Let’s look at a fictional SaaS scenario and a real‑world example.

Fictional SaaS example. Imagine your theme is “Improve onboarding & activation.” One epic might be “First‑time user flow redesign.” The stories under this epic could include:

- Signup wizard: Guide users through account creation with progressive disclosure.

- Welcome tutorial: Provide an interactive walkthrough of core features.

- Retention email drip: Send targeted emails during the first week to encourage activation.

- First task guidance: Suggest an initial task relevant to the user’s use case.

Each story delivers value on its own yet collectively they achieve the epic’s outcome of increasing activation.

Real‑world example. ProductPlan’s learning centre visualises epics sitting between themes and stories. One epic under the theme “Increase app trial users” is “Simplify download process.” It’s broken into stories such as “shorten signup form” and “move form from website into app”productplan.com. Another epic under the same theme focuses on installation, with stories like “auto‑detect details needed for install.” This structure demonstrates how epics link strategic goals to actionable work.

These examples show that epics aren’t just big tasks. They’re cohesive chunks of value that coordinate multiple stories across design, engineering and marketing.

Seen together, these scenarios illustrate what is an epic in product management in action.

Writing and structuring epics

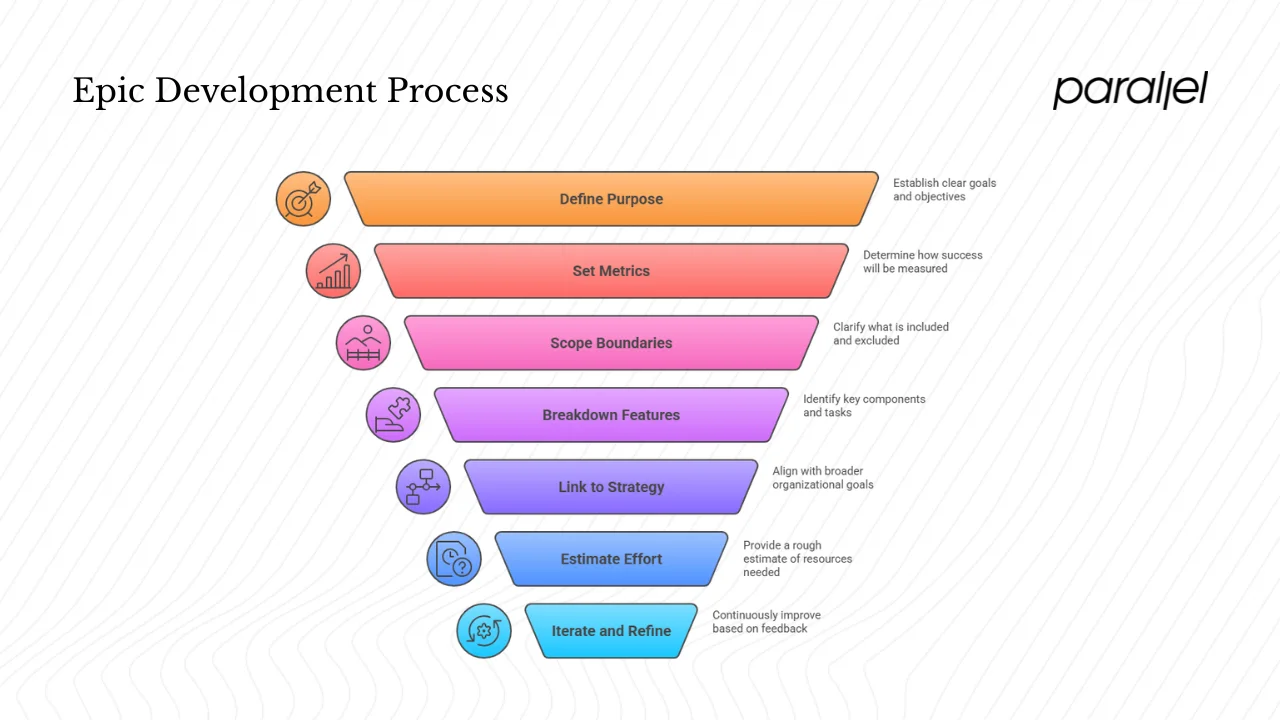

When founders ask me what is an epic in product management, they often follow up with “How do I write one?” Here’s a lightweight approach that balances clarity and agility:

- Name and purpose. Give the epic an action‑oriented title and short description. For example, “Redesign checkout process” with a purpose like “reduce cart abandonment by 20%.”

- Outcome and success metrics. Define how you’ll measure success. This could be a metric (e.g., trial‑to‑paid conversion) or a qualitative outcome.

- Scope boundaries. State what’s in scope and what’s not. Clarity prevents scope creep.

- Breakdown. List the main features or story groups within the epic. Use a user story map to identify activities and tasks.

- Link to strategy. Connect the epic to a theme or initiative in your roadmap. In your tool, link downstream stories and associate relevant OKRs.

- Estimate. Provide a rough estimate (story points or t‑shirt size) to help prioritisation.

- Iterate. As development progresses, refine or split the epic. Atlassian emphasises that scope is flexible; user stories are added or removed based on feedback.

Remember: an epic is not a specification. It’s a container for learning and iteration. Write just enough to align the team, then evolve it as you discover more.

Planning, tracking and adapting epics

Knowing the definition is only half the battle; the other half is planning and tracking. Here are practical guidelines:

- Map epics to releases: Use epics as slices on your roadmap. For an early‑stage startup, limit active epics per quarter to avoid spreading your small team too thin.

- Prioritise based on value and risk: Score epics against criteria like reach, impact, confidence and effort. Prioritise epics that advance your strategy or reduce critical risks.

- Visualise progress: Create epic burndown or burnup charts. Add swimlanes on your board for each epic. The State of Agile report shows that 32% of organisations tie OKRs to epics and track progress against them.

- Embrace change: Epics are dynamic; adjust them as you learn. Split an epic if it grows too big, merge if goals converge, or drop it if it no longer aligns with strategy.

- Define done: An epic is complete when all constituent stories meet their acceptance criteria and the intended outcome is achieved. Only then should you mark it done and communicate completion to stakeholders.

Your planning process should remain lightweight. The goal is to keep teams focused on outcomes, not to generate documentation.

Always return to what is an epic in product management when planning and tracking; anchoring your plans in the definition keeps the scope focused on delivering a specific outcome.

Pitfalls and best practices for early‑stage teams

Misunderstanding what is an epic in product management leads to common mistakes. Avoid these traps:

- Calling oversized stories epics: Stories longer than a sprint are just poorly scoped stories. Break them down before grouping them.

- Running too many epics at once: For a five‑person startup, two or three concurrent epics is plenty. More than that reduces focus.

- Over‑engineering the hierarchy: If you have only a handful of stories, epics are unnecessary. Don’t add layers for the sake of it.

- Grouping unrelated tasks: An epic should unite stories toward the same outcome. Random tasks under an epic suggest poor scoping.

- Lack of ownership: Assign a product manager to own the epic. Without ownership, scope and priorities drift.

- Ignoring feedback: Epics should evolve. Revisit them after each sprint; remove or add stories based on what you learn.

Best practices are simple: start lean, revisit regularly, limit concurrent epics, define clear outcomes, and visualise progress. Use the simplest tooling that provides traceability.

When to use and when not to use epics

If you’re still unsure whether to use epics, consider whether you need them at all. Epics are valuable when your product or organisation reaches a certain complexity:

- Use epics when multiple teams work on related functionality, when you’re coordinating across sprints or when you want to bridge strategy and execution.

- Skip epics in very early MVP stages or on small projects that fit into a couple of sprints. The overhead isn’t worth it for a tiny backlog.

- Scale thoughtfully. In large organisations or frameworks like SAFe, epics can become multi‑month investments requiring lean business cases. At Parallel, we tailor the size and process of epics to the team’s maturity rather than blindly adopting enterprise practices.

Conclusion

Epics transform chaotic backlogs into coherent, outcome‑oriented plans. They group related stories under a clear objective, linking your vision to the work your teams execute. Throughout this guide we’ve answered what is an epic in product management, explored how epics fit into the Agile hierarchy, shown examples, shared writing and planning techniques, and highlighted pitfalls. The takeaway: use epics as a flexible structure for organising complex work, but keep them lean and tied to measurable outcomes. By mastering epics, you can lead your team with clarity, deliver value faster and iterate effectively.

FAQ

1) What is an example of an epic?

An epic such as “Redesign onboarding flow” includes stories like “signup wizard,” “welcome tutorial,” “retention email drip,” and “first task guidance.” Another epic might be “Integrated analytics dashboard,” with stories around data ingestion, visualisation, export and alerts.

2) What is the difference between Agile and an epic?

Agile is a methodology or mindset centred on iterative development, collaboration and responding to change. An epic is a concept within Agile used to group related stories into a larger body of work.

3) What does the term epic mean here?

It means a large user story broken into smaller stories and tasks. The Nielsen Norman Group describes an epic as a “large user story” that can be divided into smaller stories and tasks across multiple sprints.

4) Do product managers write epics?

Yes. Product managers, often called product owners, typically define epics and own their prioritisation and delivery. Kerstin Exner notes that epics are usually written and maintained by the product owner or product manager, though the stories within are a collaborative effort.

.avif)