What Is a Field Study? Guide (2026)

Learn about field studies, observing users in their natural environment to understand real‑world interactions.

I’m often asked what is a field study and why a busy founder or product manager should bother. Products live in messy, everyday places. In our work with early‑stage machine‑learning and SaaS teams at Parallel, we see how decisions made in conference rooms drift from daily use. A field study is the simple act of leaving the building to watch, listen and gather clues from people where they actually work. It means showing up where customers drive, assemble or relax and letting reality guide your choices.

What is a field study?

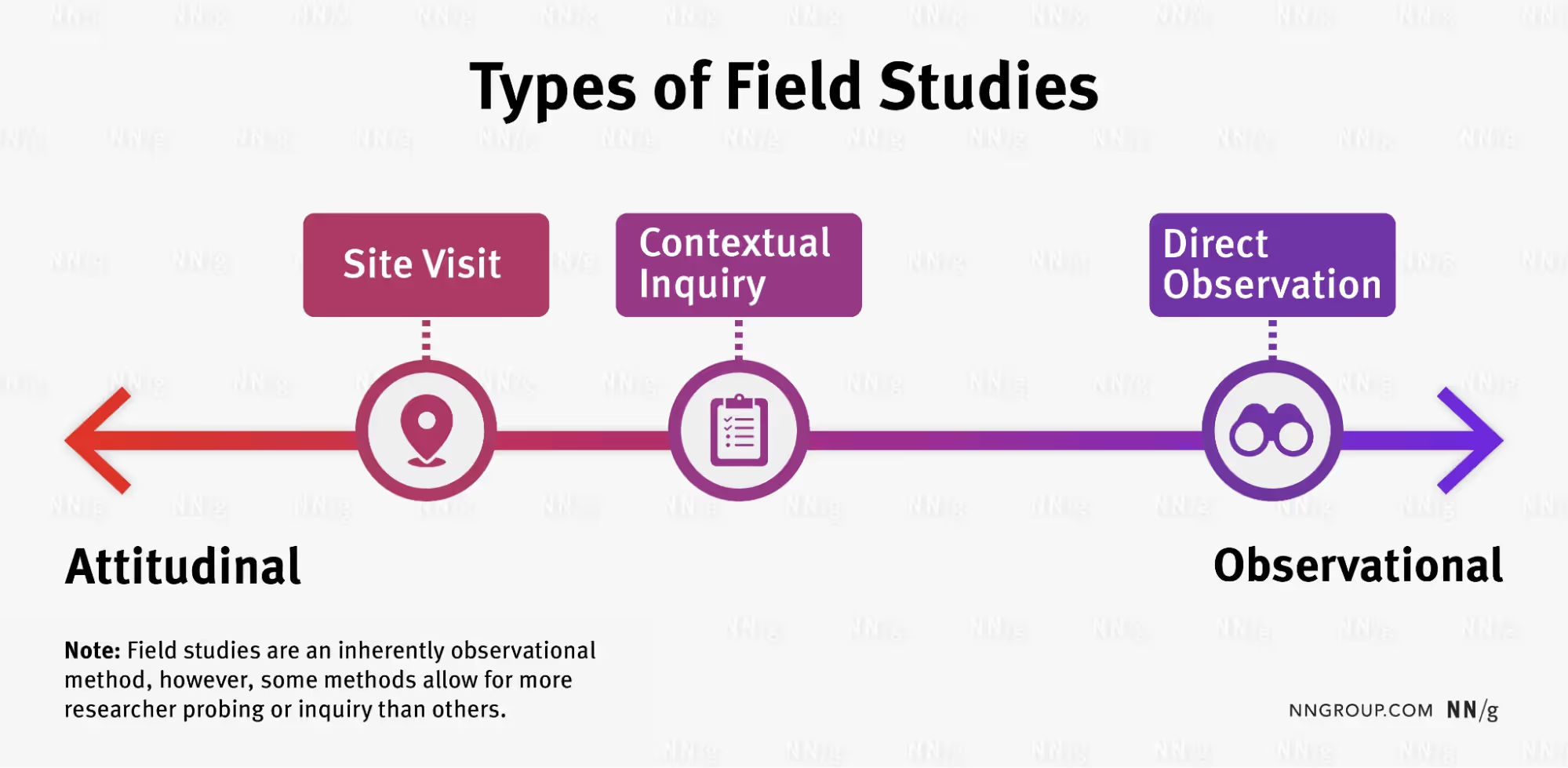

A field study is a research method that involves collecting data in the participant’s usual setting. As Nielsen Norman Group states, it’s a type of contextual research done “in situ,” meaning in place. Instead of bringing people into a lab, the researcher goes where the action happens and watches tasks unfold without rearranging the situation. Dovetail describes it as observing, interviewing and interacting with people in contexts such as workplaces or communities. Field studies vary widely. At one end you might quietly watch how a nurse charts medication in a hospital corridor. At the other you might live alongside a team for weeks to understand how they make decisions.

Two elements distinguish a field study from other methods. First, it’s grounded in the real world. You see distractions, time pressure, noise and social dynamics that seldom appear in remote or lab sessions. Second, it blends observation with conversation. While you might keep silent during a direct observation session, contextual inquiries allow you to ask short questions about what you’re seeing. The result is an empirical study that captures both what people do and why they do it.

Why field studies matter for startups

Startups often build features based on assumptions, chat messages or analytic dashboards. Those clues are useful but incomplete. Products live in messy places—from kitchens to factory floors to cars. A field study uncovers how those contexts shape use. In our experience at Parallel, early‑stage teams are prone to misjudge how little time users have, how tools compete for attention or how physical environments constrain screen‑based interactions. By stepping outside and conducting a field study, you anchor innovation in reality.

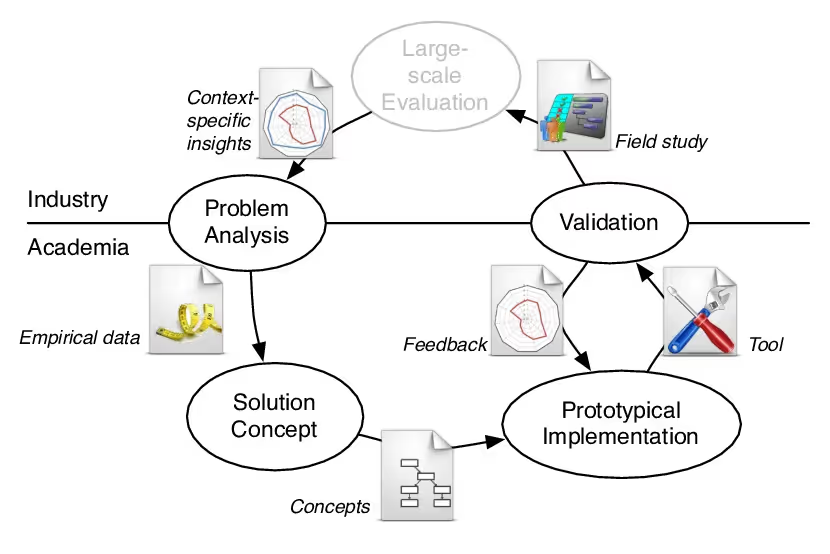

Recent data underscores this point. UXinsight’s 2024 UX Research Maturity Benchmark surveyed 455 research professionals and found that methods and operations—including field studies—are one of six core pillars of mature research practices. Teams at the ‘Established’ and ‘Pioneering’ maturity levels integrate research directly into decision‑making, showing how investing in on‑site research pays off.

Authenticity is the greatest benefit. Observing natural behavior reveals work‑arounds, jargon and pain points that won’t surface in a controlled session. This context helps teams prioritise problems, understand constraints like glare or bad connections and avoid building unused features. A field study also builds empathy within the team.

Types of field studies

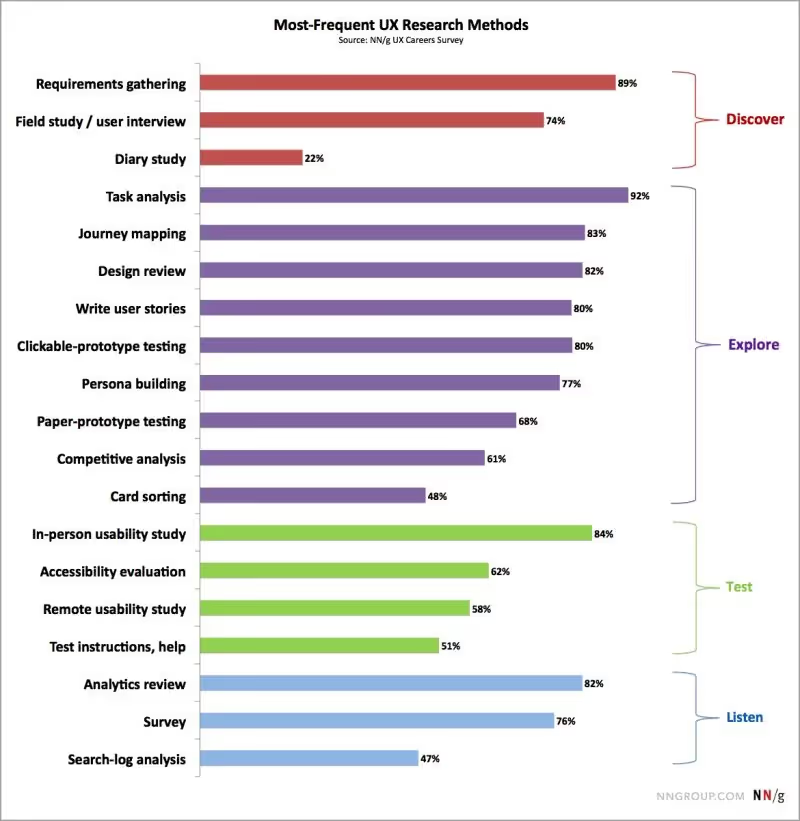

Nielsen Norman Group and other sources describe several variants of field studies. Each balances observation and interaction differently:

- Direct observation – watch people perform tasks in situ without intervening; use this to map flows and jargon.

- Contextual inquiry – combine observation with quick questions to understand reasoning without disrupting the activity.

- Customer‑site visits – tour a client’s workplace and discuss processes, learning about constraints first‑hand.

- Ethnography – immerse yourself for an extended period to understand social norms and practices.

- Participant observation and qualitative interviews – take part in activities and talk to people to build trust and gather context.

The choice depends on your goals, resources and how much you can intrude. Many teams start with observation and add contextual questions as they learn.

How to plan and conduct a field study

Planning a field study demands care. Keep it simple with these steps:

- Define your question – specify the behavior or context you want to understand.

- Pick the site – visit natural habitats, workplaces or events where the behavior occurs.

- Choose methods – mix observation, brief interviews, surveys or document analysis.

- Recruit and get consent – work with organisations and participants to secure permission.

- Decide observers – limit the number of observers and assign roles to minimise disruption.

- Plan logistics – schedule sessions, bring appropriate recording tools and consider ethics.

- Debrief quickly – summarise observations soon after sessions to keep details fresh.

Following these simple steps helps your field study run smoothly and yield insights.

Data collection and analysis

Field studies generate rich data. Collect it by watching tasks as they happen, asking participants to explain their choices, and reviewing surveys or existing documents. While field studies are primarily qualitative, counting behaviors or time intervals can help you communicate findings. After collecting data, cluster observations into themes and compare them with your expectations. Summarise patterns to inform design decisions. Be mindful of the Hawthorne effect—people may alter behaviour because they know they’re being observed. Build rapport and spend enough time on site so participants feel comfortable. Use simple tools like checklists, photos or video to capture details without constantly interrupting. Analysis should involve multiple perspectives; having team members from design, product and engineering review the data can reveal different angles. Visualise patterns with experience maps or storyboards to make findings tangible and shareable.

Advantages and drawbacks

When someone asks what is a field study, they often want to know if going on site is worth it. The answer is yes—field work provides authentic insights, flexibility, rich data and the chance to discover behaviors you didn’t anticipate. The trade‑offs are cost and time, limited control over variables, potential bias and complex logistics. Weighing these factors helps you decide whether a field study makes sense for your project. You can reduce some drawbacks by planning carefully: combine remote and on‑site sessions to lower travel costs, train observers to minimise bias, and choose manageable sample sizes. These adjustments help you gain context‑rich insights without overstretching your team.

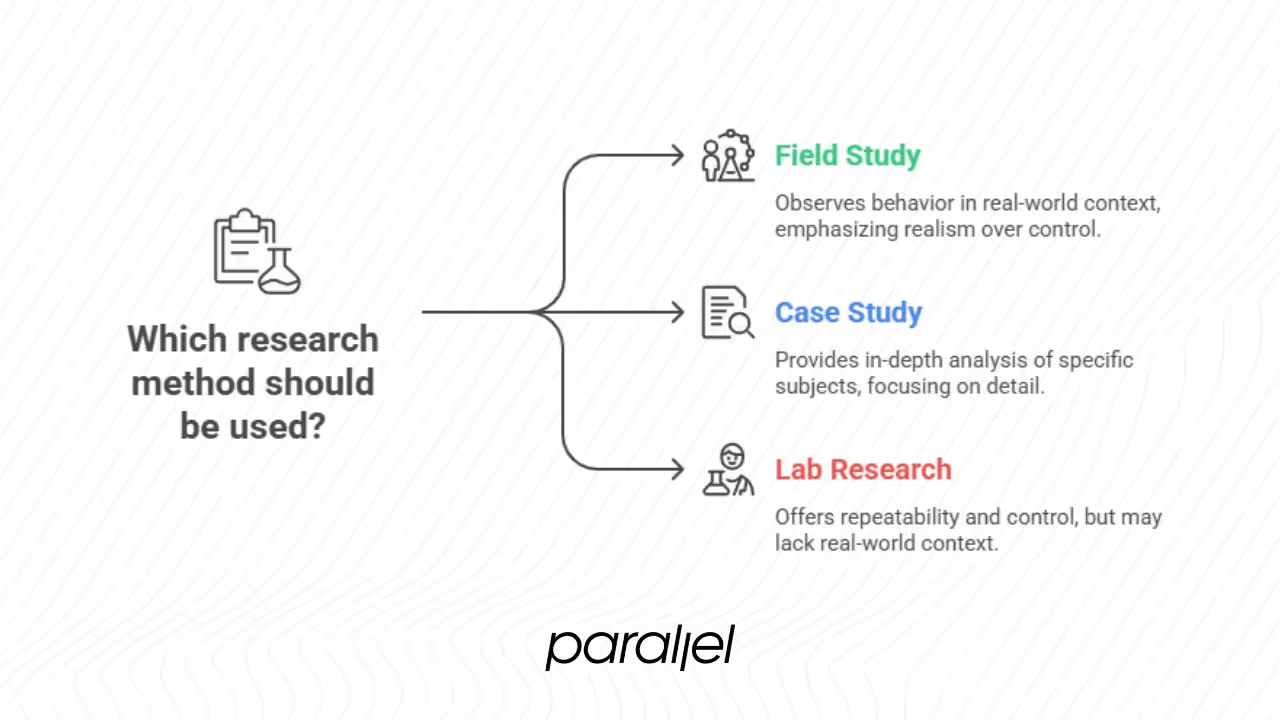

Field study vs. case study and other methods

People sometimes confuse field studies with case studies or lab research. Knowing what is a field study helps: a field study observes everyday behavior in context, whereas a case study is a deep dive into a specific person, group or event. A field study trades control for realism, while lab or remote research offers repeatability but may overlook environmental factors. Use controlled methods to fine‑tune interactions and field work to understand context and constraints.

When to run a field study

Field studies are valuable at multiple points in the product lifecycle. In early discovery, visiting users helps you see their current work‑arounds, constraints and goals before you commit to a solution. Watching real behaviour before you design prevents misaligned solutions. Later, field testing prototypes in realistic settings shows whether designs hold up under real conditions, such as a busy shift or noisy car. A start‑up might begin with quick contextual inquiries to grasp how people do a task, then return with a prototype to see how it fits into everyday life.

Field research also plays a role in continuous improvement. After launch, periodic site visits can uncover emerging needs and inform the roadmap. Some teams run remote observations or diary studies between visits, but being on location helps you catch subtle cues like body language and workspace constraints. For resource‑constrained teams, targeted visits to high‑risk contexts or mission‑critical workflows deliver outsized value. If travel is impossible, video calls with screen sharing can approximate context, though you’ll miss some environmental clues.

Real‑world examples for product teams

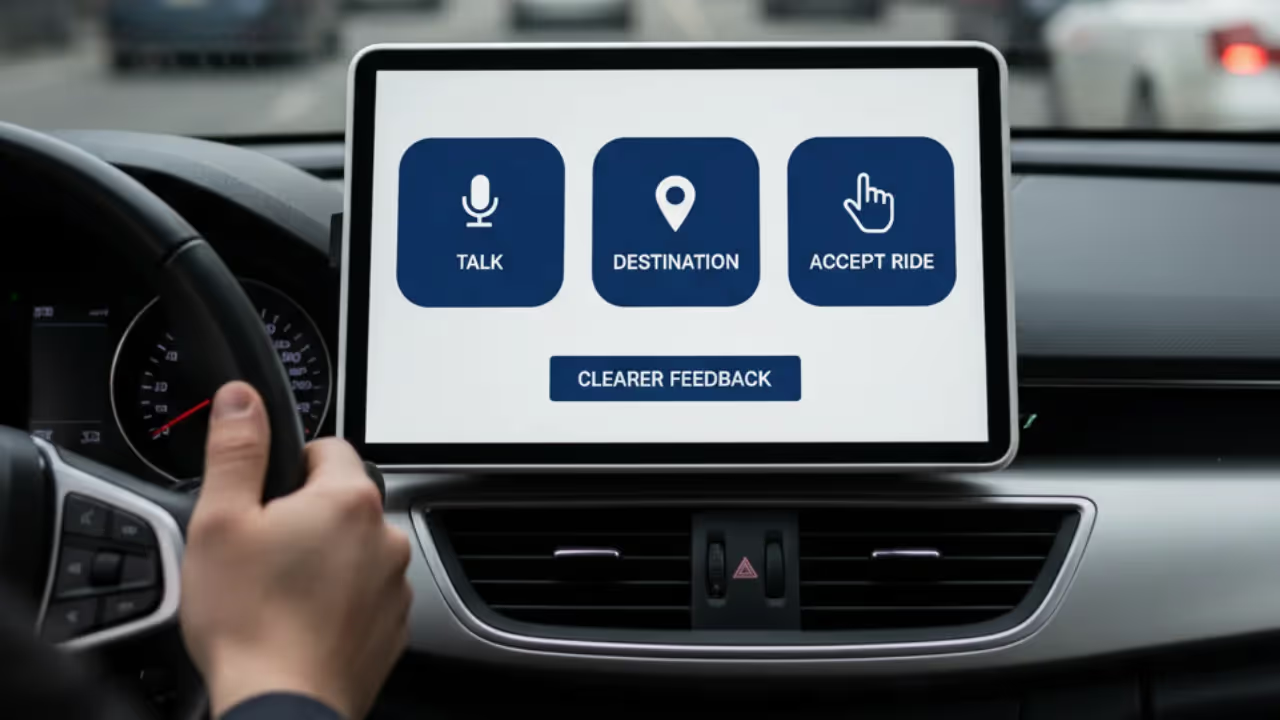

Clients often ask us what is a field study when facing puzzling usability issues. For one voice assistant, riding with drivers showed us how road noise and stress made small touch targets unusable; larger buttons and clearer feedback improved adoption.

On a factory‑floor project, we learned that gloves and grease made touchscreens impractical, so we added physical buttons and simplified steps. These visits illustrate how on‑site research reveals constraints that no office session would expose.

Another engagement involved customer support agents juggling multiple chat windows and phone calls. Observing them in their hectic workspace showed us that simple colour coding wasn’t enough; we redesigned notifications to use motion and sound cues so high‑priority chats stood out. Such insights are hard to spot when you’re not sitting in the room.

Tips for startup product teams

If you’re still wondering what is a field study, think of it as an on‑site check that helps ground your thinking. If you’re considering a field study, keep it manageable.

Start with a single context or user group. Short contextual inquiries or customer‑site visits can yield valuable data without huge expense. Invite stakeholders thoughtfully; one or two observers are fine, but a crowd can intimidate users. Set clear rules for observers: stay quiet, jot down observations and debrief later. Finally, share field stories with your team through short clips or written narratives to build empathy and understanding.

Field studies don’t always mean long engagements. You can run a series of short, focused visits to answer specific questions. For example, spend a morning shadowing users during peak tasks, then regroup to synthesise insights. Pair these visits with remote research—use surveys or analytics to identify patterns, and then go on site to understand them. Bringing engineers or executives along occasionally accelerates decision making by giving them firsthand exposure. After each study, share highlights through stories, photos or short clips to keep the learnings alive and build empathy across the team.

Conclusion

Field studies are a powerful way to ground product work in the realities of daily life. By answering what is a field study with on‑site observation and interaction, founders and product leaders gain insight that no survey or analytic dashboard can provide.

The method isn’t a panacea—it takes time, money and planning—but when used thoughtfully it can help early‑stage teams make better decisions, avoid costly mistakes and build products that fit naturally into people’s lives. In a world awash with remote tools and broad metrics, stepping into your users’ shoes (or cars, kitchens or factories) remains one of the most human and effective research practices.

As user research matures, field studies remain a way to ground innovation in reality. They remind us that great products start with observing people where they work. That is the essence of what is a field study.

FAQ

1) What do you mean by field study?

A field study involves observing and collecting data in participants’ everyday environments rather than a lab, often mixing watching with short conversations.

2) What are the three types of field studies?

Common types include direct observation, contextual inquiry and ethnography; some researchers also count customer‑site visits and participant observation.

3) What is education field study?

It means studying teaching and learning in real classrooms or learning communities.

4) What is the difference between a case study and a field study?

Case studies dive deeply into a specific person, group or event, while field studies observe behaviour in natural contexts over time.

.avif)