What Is a Forcing Function? Guide (2026)

Understand the concept of a forcing function in business and design, and how it drives desired behaviors or outcomes.

You have a product idea and a lean team. After the initial rush, progress slows. Discussions drift and decisions wait for another meeting. This is common for founders and product managers when the idea is clear but execution stalls. In those moments we often ask, "what is a forcing function and how can it help?" A forcing function is an external constraint such as a deadline, public promise or blocking step that compels action and turns "we should" into "we must."

A quick answer: what is a forcing function? It’s something that introduces pressure or a clear boundary so you move. Without it, the gap between motivation and accountability widens, deadlines slip and momentum ebbs. Forcing functions bridge that gap by making commitments visible and raising the stakes for follow‑through. In this article you’ll learn how they work, the types you can use, real examples, design steps, when not to use them, their impact and a brief case story.

What is a forcing function?

A forcing function is a constraint or scheduled boundary that transforms “we should” into “we must” by making inaction costlier than action.

Chris Sparks, who coaches executives and named his company after the concept, explains that a forcing function is a catalyst that changes your default behaviour in the future by matching near‑term incentives with long‑term goals. In his experience, forcing functions usually take the shape of a commitment or a pre‑scheduled event that demands progress. They bring attention to the work at hand and put you in a position where excuses are harder because someone else is expecting a result.

In the world of product and interaction design, a forcing function is an aspect of a design that prevents a target action from being performed or allows it only when a prior action happens first. Examples include cars that do not shift into reverse unless the driver presses the brake, microwaves that will not open while running or hospital policies that remove concentrated potassium from wards to prevent mixing mistakes. Don Norman, in The Design of Everyday Things, classifies design forcing functions into interlocks (operations that must happen in a set order), lock‑ins (keeping an operation active until completion) and lock‑outs (preventing access to hazardous situations). These constraints are not about punishing users but about guiding behaviour toward safe or desired outcomes.

In behavioural psychology, forcing functions work because deadlines, external pressure and accountability can shift behaviour. A self‑imposed goal often lacks urgency; adding a constraint raises the perceived cost of inaction. Sparks observes that deadlines, externalization (getting goals out of your head), accountability and stakes are important mechanisms: a looming deliverable gives focus, sharing your intent creates social pressure, and raising the stakes makes failure more painful.

The role of deadlines and constraints

Forcing functions mix motivation and constraint. Pure motivation without structure often stalls when priorities compete or energy dips. A deadline, however soft, creates a boundary in time that encourages focused effort. External pressure – such as a customer expecting a demo – adds consequence. Accountability to peers or mentors means someone will notice if you miss a step. Together, these elements push action forward. In product work, this can make the difference between shipping a feature and staying in analysis mode.

A forcing function differs from discipline. Discipline is an internal drive to do what is needed regardless of circumstances. It grows over time and can waver under stress. A forcing function is external scaffolding. It does not replace personal drive but supports it by reducing the choice to procrastinate. Think of it as placing a meeting on the calendar that you must attend – your internal drive might not be enough to get you there every time, but the calendar event and the peers expecting you nudge you to show up.

Forcing functions also complement other productivity tools. Reminders help you not forget tasks; habit loops build routines; incentives provide rewards. A forcing function, by contrast, combines constraint with motivation. It forces your short‑term actions to match your longer‑term priorities. It therefore belongs in the same toolkit as timeboxing, personal trainers, and other systems that help you get important work done.

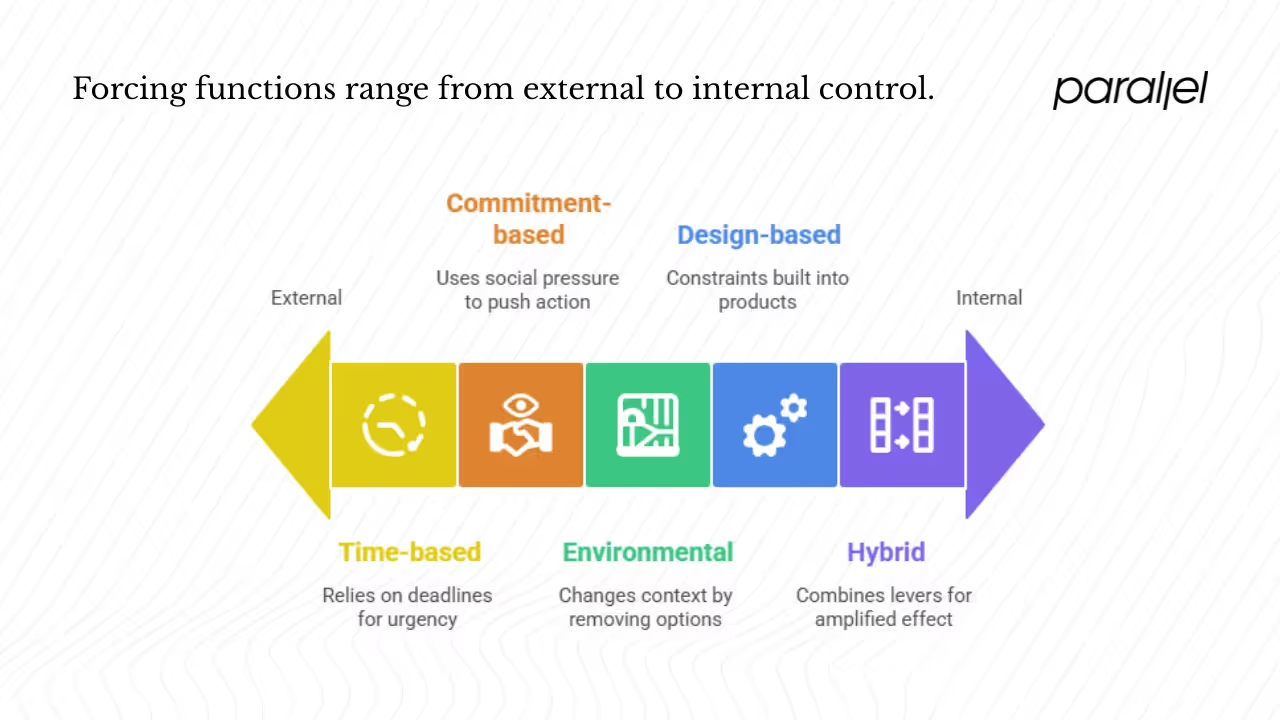

Types of forcing functions

Forcing functions vary by the mechanism they use. Understanding the variants helps you choose the right approach for your team or product.

1) Time‑based forcing functions

Time‑based forcing functions rely on deadlines and windows—soft or hard dates, milestones or trial periods—that create urgency and encourage focus.

Soft deadlines like weekly demos provide a cadence with some flexibility, while hard deadlines such as a contractual release date or an upcoming conference are fixed and non‑negotiable. Trial periods and limited‑time offers also compel decisions before a window closes, making them another type of time‑based forcing function.

2) Commitment and accountability‑based forcing functions

Commitment and accountability mechanisms use social pressure—public promises, peer check‑ins, financial stakes or formal contracts—to push action.

Public promises create reputational risk and drive follow‑through, while financial stakes (for example, depositing money you lose if you miss a milestone) and peer accountability harness social pressure. Written contracts, such as service‑quality agreements, institutionalise consequences for missed commitments.

3) Design‑based forcing functions

Design‑based forcing functions are constraints built into products. They include interlocks, lock‑ins, lock‑outs and confirmation prompts that prevent dangerous or premature actions.

Interlocks ensure that users can't skip essential steps, lock‑ins keep processes active until completion and lock‑outs prevent dangerous actions. Confirmation prompts and two‑person rules slow users down intentionally to reduce errors. Designers also use cognitive forcing functions: some systems require a user to sketch or write an idea before seeing machine‑generated output, reducing the risk of blindly accepting suggestions.

4) Environmental and structural forcing functions

Environmental forcing functions change context by removing options or automating triggers, such as meeting‑free blocks, gated reviews or dedicated spaces that focus attention.

Meeting‑free mornings and standing meetings adjust the context to make deep work or brevity the default, and manufacturing lines enforce one‑way flow to prevent rework. Constraints can also be built into systems via gating or automation: a continuous integration pipeline that blocks code merges until tests pass or an expense policy that rejects submissions without receipts reduces friction for compliant behaviour and increases it for unwanted actions.

5) Hybrid forcing functions

Many teams combine these levers into hybrid forcing functions like weekly demos, hack weeks or release trains that mix time, accountability and environment. To understand what is a forcing function, categorize them by time, commitment, design, environment and hybrids.

Hybrid forcing functions mix multiple levers to amplify their effect. Weekly review meetings combine a time‑box with peer accountability and a blocked calendar slot, hack weeks blend a timebox, a change of environment and peer pressure, and release trains synchronise releases to a fixed cadence with gating conditions like tests and reviews. Mixing levers often creates stronger momentum than using a single lever alone.

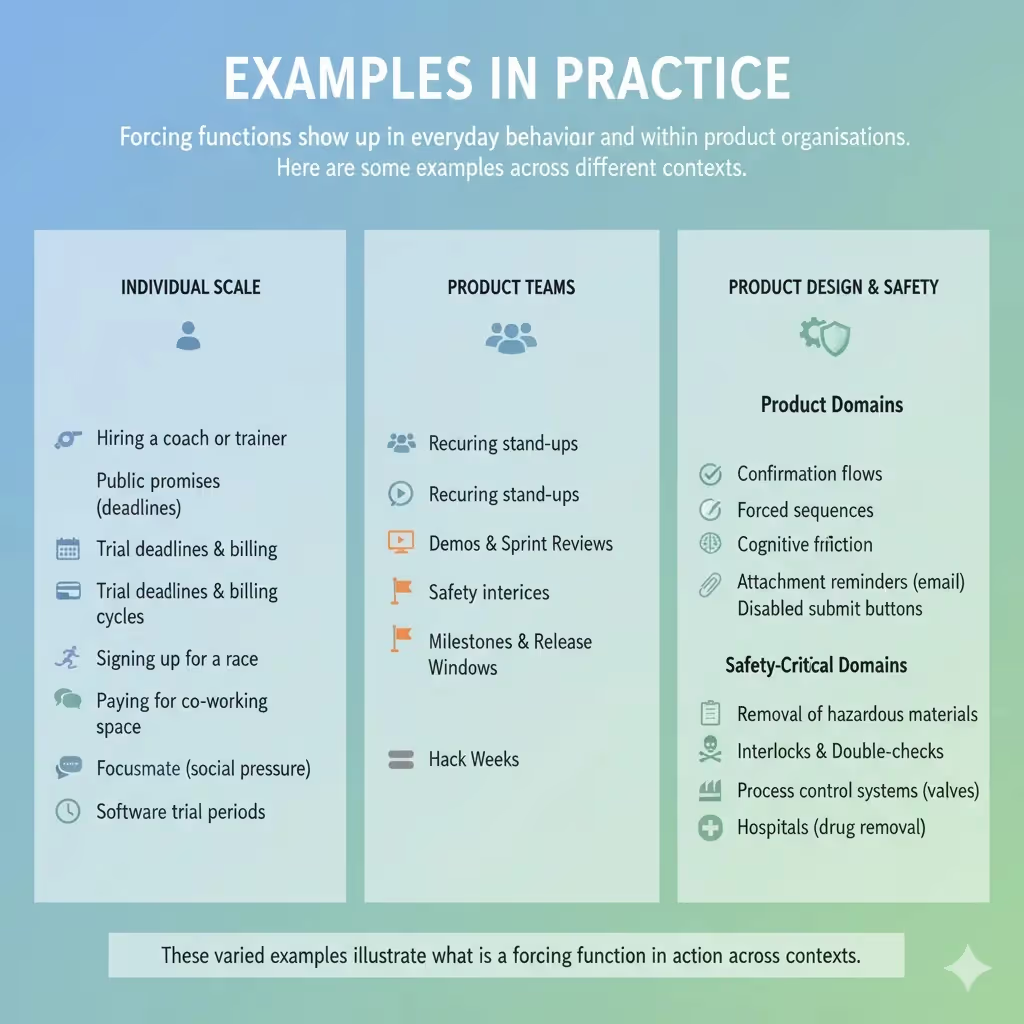

Examples in practice

Forcing functions show up in everyday behaviour and within product organisations. Here are some examples across different contexts. At an individual scale, forcing functions include hiring a coach or trainer, making public promises about delivery dates, or relying on trial deadlines and billing cycles to force a decision. Within product teams, recurring stand‑ups, demos, milestones, release windows and hack weeks create regular points of accountability that push work forward. In products themselves, confirmation flows, forced sequences, safety interlocks and cognitive friction serve as design‑based forcing functions. In safety‑critical domains, checklists and the removal of hazardous materials prevent dangerous actions. These varied examples illustrate what is a forcing function in action across contexts.

Individuals often create forcing functions without realising it. Signing up for a race or paying for a co‑working space introduces a date or cost that makes procrastination painful. Services like Focusmate match you with a stranger for a focused session, harnessing social pressure, and trial periods on software force you to test and decide before access expires.

In teams, stand‑ups, demos, sprint reviews, and hack weeks are everyday forcing functions that create cadence and accountability. Design patterns such as attachment reminders in email clients or disabled submit buttons protect users, and safety‑critical domains use interlocks and double‑checks to prevent accidents. Process control systems require valves to operate in a specific sequence, and hospitals remove high‑risk drugs from general storage.

Designing and implementing a forcing function

Introducing a forcing function is deliberate. You want to encourage progress without causing unnecessary stress. Below is a process for creating one. To create a forcing function, start by identifying the behaviour you want to trigger. Before you decide what is a forcing function for your situation, pick a mechanism—time, accountability, design or environment—that fits your context. Calibrate its intensity so it nudges without overwhelming. Leave some slack for exceptions, monitor results and adjust. Finally, explain the rationale to your team and start small to build trust.

Start by deciding what behaviour or outcome you want to encourage and why it isn’t happening. Are you trying to increase code review throughput, shorten cycle time or reduce errors? Write down the target and examine where the process is slipping—lack of urgency, unclear ownership or distractions. Choose a lever that matches the problem: a time‑box for inertia, public commitments for accountability, design constraints for error prevention or environment changes for focus.

Once you’ve chosen a lever, calibrate its intensity and leave some slack. A daily checkin might be too much for senior teams but just right for new hires; a hard deadline may motivate but could sacrifice quality if unrealistic. Start small and adjust based on feedback. Buffer time and exceptions prevent the forcing function from becoming oppressive.

Finally, monitor and iterate. Track metrics like cycle time, defect rates or meeting attendance to see if the forcing function has the desired effect. Explain why you’re adding the constraint and share examples of success. People resist arbitrary rules, so transparency and a small pilot build trust. Good forcing functions adapt with the team; they support discipline without replacing it.

Common pitfalls and anti‑patterns

Used poorly, forcing functions can backfire. Too many hard deadlines and mandatory deliverables feel like micromanagement and can erode intrinsic motivation, causing people to cut corners. They can also mask deeper problems when hitting the constraint becomes a goal in itself. Without monitoring and feedback, stress builds and burnout follows.

Another common anti‑pattern is using the wrong lever. A design lock‑out won’t fix a lack of accountability, and a public promise won’t prevent errors. Choose a mechanism that addresses the real behaviour you want to change and adjust it as you learn. Keep in mind that forcing functions are just one tool in your toolbox; they should support, not replace, discipline and motivation.

When not to use a forcing function

Constraints are not always appropriate. Creative work and early exploration require space and should not be bound by strict deadlines; premature constraints can produce shallow work. Senior experts need autonomy—imposing strict check‑ins can signal mistrust. And if your team lacks basic habits, like a shared definition of done or a stable backlog, adding a release train can overwhelm. Stabilise your processes before adding constraints.

Impact on metrics and performance

When well designed, forcing functions accelerate progress and reduce slippage. A recurring demo encourages teams to finish features, and agenda requirements cut wasted meeting time. They improve accountability and discipline. But there are risks: too many deadlines lead to stress; people may game the system by optimising for the wrong metric; and strict gates can create bottlenecks. Monitor these trade‑offs.

When you introduce a forcing function like a weekly demo, it often reduces slippage in tasks. People finish features so they can show them. In our coaching, teams using forced demos improved their release reliability by roughly 20–30% over two quarters. Flowtrace’s 2025 report found that 64% of recurring meetings lack an agenda and teams spend 392 hours a year in them. Introducing agenda requirements is a forcing function: meetings shrink or are cancelled if there is no plan. This can free dozens of hours per person each year.

Forcing functions also improves accountability. When you commit publicly, you’re more likely to follow through. We’ve seen teams who publish public changelogs report fewer last‑minute scrambles because everyone knows features must be ready by the next update. However, misuse can drive negative outcomes: unrealistic deadlines lead to stress, and some team members may chase visible metrics rather than meaningful work. Balance speed and quality and watch for gaming behaviour.

Financially, forcing functions can reduce waste. A release train reduces the costs of context switching and last‑minute work. Reduced meeting time translates into more focused work. But there can be hidden costs: teams may accumulate technical debt to meet deadlines or neglect long‑term improvements. Monitor metrics like defect rates, customer satisfaction and team morale to understand the full impact.

Case example: accelerating delivery with forcing functions

In 2024 we worked with a machine‑learning‑powered SaaS startup that struggled to ship on time. Stand‑ups were status reports, demos were irregular and meetings filled the week. We introduced weekly demo days, meeting‑free mornings, a two‑week release train and a public changelog. Within two months, shipped stories per train rose by about 30%, engineers completed more reviews and stakeholder confidence improved. The blend of time, accountability and environmental forcing functions illustrates what is a forcing function in practice and how small changes can build momentum.

The company had about fifteen engineers and a product manager. They lacked structure: stand‑ups were perfunctory, requirements changed mid‑sprint and stories rolled over from one cycle to the next. We introduced a two‑week release cadence, weekly demos, protected deep‑work mornings and a public changelog, creating a mix of time‑based, accountability and structural forcing functions.

Within weeks the cadence shifted. Roll‑overs dropped, engineers prepared demos each Friday and the changelog increased visibility. After two months the average cycle time fell from about twenty days to fourteen and shipped stories per release climbed roughly 30%. Team morale and stakeholder confidence improved with the steady progress.

Recap and next steps

So, what is a forcing function? It’s a thoughtful constraint—like a deadline, public commitment, design lock‑in or environmental change—that makes it harder to avoid progress. When you design one, define the behaviour, choose the right lever, calibrate its strength, allow slack and watch the impact. Use them selectively on high‑impact work. Look at your rituals and ask where you’re losing momentum. Try a small forcing function this week and observe how it influences behaviour.

Forcing functions work because they create friction in the right places. They are not about punishing people; they are about making the right choice easier and the wrong choice harder. Thoughtfully applied, they help you and your team move from intention to impact. As you experiment, be transparent about your goals and gather feedback. Over time you’ll develop a palette of constraints that spur progress without stifling creativity.

Cheat sheet

- Define the target: What specific behaviour are you trying to trigger?

- Pick the mechanism: Time (deadlines, milestones), accountability (public commitments, peer pressure), design (interlocks, confirmations), environment (context changes) or a combination.

- Set the intensity: Strong enough to nudge, not so strong that it causes backlash.

- Add slack: Allow room for exceptions and creativity.

- Monitor and adjust: Track impact, learn from side effects and refine.

Frequently asked questions

1) What is an example of a forcing function?

An everyday example is scheduling a recurring stand‑up where each team member shares what they accomplished and what they plan to do next. Knowing you will speak in front of peers pushes you to finish tasks. In design, an interlock like a microwave that won’t open while running is a forcing function because it prevents an unsafe action.

2) What are forcing functions in a product team?

For product teams, forcing functions include demos, release trains, sprint reviews, and public roadmaps. These events create natural deadlines and social pressure to deliver. They help reduce drift and bring teams back to a shared cadence.

3) What is a forcing function in process control?

In process control, a forcing function is a mechanical or software interlock that ensures safe operation. For example, chemical plants often require valves to close in a specific sequence to prevent explosions. In healthcare, removing hazardous substances from areas where they might be misused is a forcing function.

4) How are forcing functions used in healthcare?

Healthcare forcing functions involve design changes or policies that prevent dangerous actions. Examples include drug connectors that only fit the correct port, protocols that require double checks before medication administration, or checklists that must be completed before surgery. These functions remove the option to skip critical safety steps.

5) Can forcing functions stifle creativity or motivation?

If overused or too rigid, forcing functions can feel constraining and dampen creativity. They work best when applied to well‑defined tasks that need momentum. For exploratory work, softer nudges like regular sharing sessions or soft deadlines can provide structure without limiting exploration. Balance constraint with autonomy.

6) How strong should the forcing pressure be?

A forcing function should be strong enough to nudge behaviour but not so strong that people feel trapped. Start with modest constraints and increase only if needed. Observe how the team responds. If resistance rises or quality drops, reduce the intensity. The goal is to encourage progress, not to coerce.

7) Are forcing functions manipulative?

Not if used transparently. A forcing function should be explicit and fair. You’re not tricking people; you’re setting clear expectations and consequences. The purpose is to support shared goals, not to trap or shame team members. If a forcing function feels manipulative, revisit the rationale and be open about why the constraint exists.

8) How do forcing functions differ from habits?

Habits are internal patterns of behaviour formed through repetition. Forcing functions are external mechanisms that create conditions under which action is more likely. Over time a forcing function can help cultivate a habit—for example, a recurring daily stand‑up can encourage consistent daily progress—but the two concepts are distinct. Habits persist without external pressure, whereas a forcing function stops working when removed.

9) How do I know if my forcing function is working?

Measure the outcome you care about—cycle time, number of completed stories, fewer errors or more consistent meeting attendance. Compare your baseline metrics with those after introducing the forcing function. Also pay attention to qualitative signals: Do people feel less overwhelmed? Is quality improving? If the numbers don’t move or morale drops, tweak or retire the forcing function.

.avif)