What Is Generative Research? Guide (2026)

Discover generative research, which explores user needs and motivations to inspire new product ideas and designs.

Most early‑stage new companies fall into the same trap. They see an opportunity in the market and rush to build a product. Months later they realise that they’ve been solving a problem that doesn’t really matter to the people they’re hoping to serve. When you skip the step of truly understanding your customers, you risk wasting time, money and team morale.

This piece, drawn from Parallel’s experience working with dozens of machine‑intelligence and SaaS teams, explains what generative research is and why it matters. We’ll share how it differs from other research approaches, when to use it, common methods and how to get started. The goal is to help founders, product managers and design leaders build solutions grounded in real user needs.

What is generative research?

Generative research is a qualitative approach that investigates people’s needs, behaviours and motivations before a solution exists. Rather than starting with a product idea, you start with questions about the world: What problems do our potential customers face? How do they behave in a given context? What motivations or constraints shape their choices? An official government guide on user research defines it as work that “helps you discover behaviours and problems in the current environment” and suggests it is the type of research you use at the very start of a project. The focus is not on evaluating a prototype or design; it’s on generating a deep understanding of people’s lives.

The word generative reflects the purpose of this work. By uncovering hidden patterns and unmet needs, it generates new ideas and opportunities. Lyssna’s 2025 overview says that generative studies “seek to generate insights about users and their behaviour” and are often called discovery or exploratory research. Conducted early in the product development cycle, such research surfaces insights that can inspire innovative solutions.

Why generative research matters for new companies

1) Understand unmet needs

Many new companies fail because they misread the market. Founders Forum’s 2025 report on new company statistics points out that 42% of new companies collapse because they create products that nobody wants, while others fail due to funding issues (29%), team issues (23%) or competition (19%). In our work with early‑stage SaaS teams, we’ve seen well‑intentioned founders build beautiful dashboards only to find out later that customers needed something entirely different. Generative research forces you to slow down and ask “What is the real problem here?” before investing heavily in a solution.

2) Encourage creative exploration

When you start with an open mind, you allow surprising insights to surface. Instead of testing assumptions, generative research invites you to hear stories. In our sessions we’ve uncovered things like “I use spreadsheets because our team chat doesn’t have reminders” or “I’m afraid of automation because my manager tracks my every move.” These conversations inspire new directions you never considered. According to Lyssna, the questions driving generative studies include “What problems exist in this space? Why do users behave this way? What are users’ unmet needs and motivations?”. Asking these questions early opens space for bold ideas.

3) Reveal patterns missed by data

Analytics and A/B tests show you what users do, but not why. Interviews, observations and diary studies reveal the emotional drivers behind behaviour. A government guide observes that generative techniques like watching users carry out tasks or interviewing them help uncover behaviours and problems.

Quantitative data is valuable, but without context you risk misinterpreting patterns. In one of our projects, sign‑up completion rates were low. Data suggested the sign‑up fields were too long, but interviews showed that users dropped off because they were worried about sharing their bank details. That insight prompted a redesigned onboarding flow and a trust‑building explanation page.

4) Identify problems before building

Generative research helps you avoid the “build trap.” Teams often spend months building features that never see adoption because the original problem was poorly understood. Alida’s 2024 guide warns that if a team relies only on evaluative research, they may refine solutions without understanding the underlying problems. Generative work surfaces those underlying pain points so you build the right thing from the start.

5) Spark innovation grounded in reality

True innovation isn’t about clever technology; it’s about solving meaningful problems in a way people appreciate. By listening to real stories, teams find inspiration. We once worked with a health‑tech new company that thought reminders and dashboards would engage patients. Interviews with caregivers revealed that the emotional toll of managing appointments was the real burden. This led to a solution focused on shared schedules and one‑tap updates rather than analytics. It’s a small example of how generative work can produce truly useful ideas.

Generative vs other types of research

Generative vs evaluative

Generative vs foundational

Where it fits in the design thinking process

In a typical design thinking loop you move from discovery to synthesis, ideation, prototyping and testing. Generative research belongs in the discovery phase. It feeds into synthesis activities like creating personas or experience maps, which in turn inspire ideation. Evaluative research happens later during prototyping and refinement. This distinction matters because early‑stage new companies often skip discovery altogether, jumping straight into prototyping. Investing in generative work ensures you’re solving the right problems.

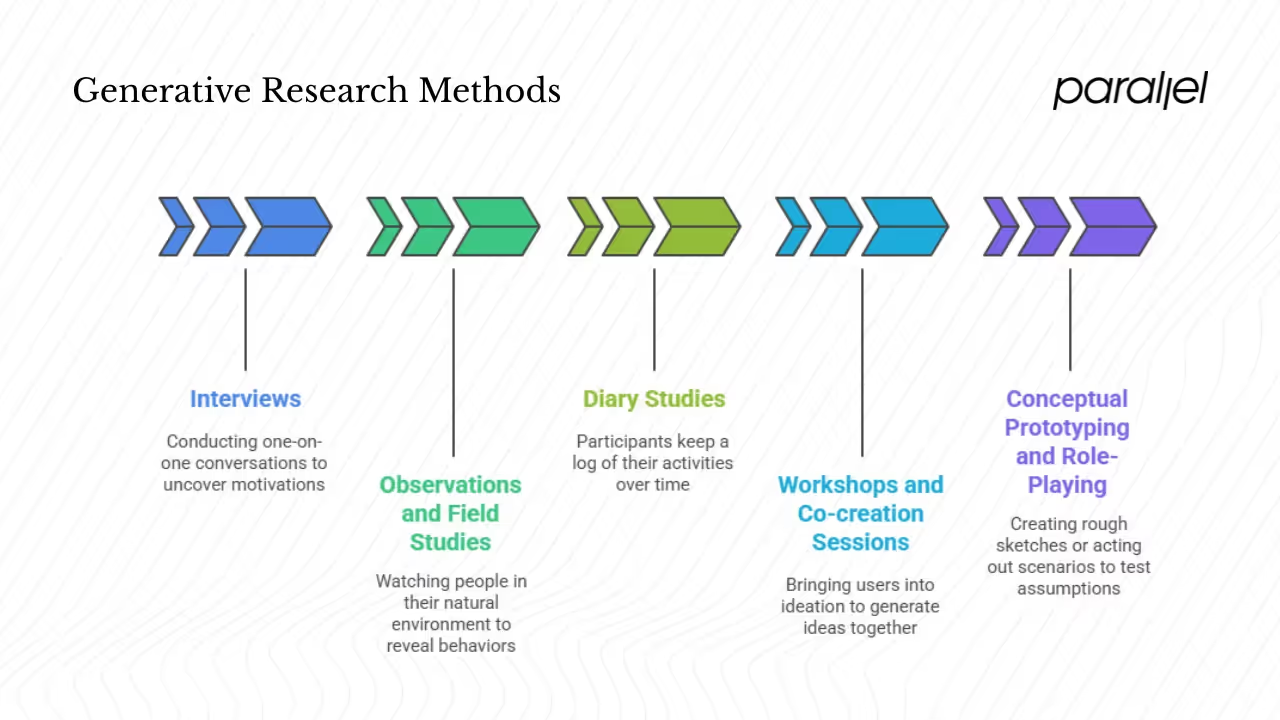

Methods of generative research

Generative research relies on qualitative methods. Below are common approaches and how we’ve used them at Parallel.

1) Interviews

One‑on‑one conversations allow you to uncover motivations and emotions. The Alida guide emphasises using open questions and listening without introducing your own hypothesis. In our practice we schedule 45‑60 minute sessions, record them (with permission) and ask about behaviour, not just opinions. A good interview guide starts with broad questions about daily habits and gradually focuses on specific problems.

2) Observations and field studies

Watching people in their natural environment reveals behaviours they may not mention. The government website lists observations and watching users carry out tasks as examples of generative research. We have shadowed warehouse workers to see how they handle inventory, noticing workarounds they didn’t think to mention in interviews. Taking photos or sketching the environment helps you recall details later.

3) Diary studies

People taking part keep a log of their activities over days or weeks. This method captures longitudinal experiences and is particularly valuable when behaviours change over time. For example, a team member may record their feelings each time they use your tool, revealing patterns like stress during month‑end reporting. At Parallel we use simple chat check‑ins or mobile diary apps to make it easy for busy people taking part.

4) Workshops and co‑creation sessions

Bringing users into ideation can be powerful. Group workshops help you understand shared experiences and generate ideas together. Lyssna includes focus groups and cultural probes among generative methods. We like to host short idea‑sketching sessions with early adopters, where they can illustrate how they would solve a problem. This not only sparks ideas but also gives people taking part a sense of ownership.

5) Conceptual prototyping and role‑playing

Even though generative research happens before formal designs, you can still create rough sketches or act out scenarios to test assumptions. Card‑sorting sessions help you understand how users categorise items. Role‑playing can reveal reactions to hypothetical services. These low‑fidelity activities keep the focus on the underlying needs rather than specific interfaces.

When should new companies use generative research?

- Early in product development cycles. When you’re deciding what problem to solve, generative work is essential. It helps you build a strong foundation rather than guessing.

- Entering a new market or problem space. If you’re pivoting your machine‑intelligence/SaaS business or exploring a completely new domain, discovery work prevents wasted effort.

- When user needs are unclear. If metrics show churn but don’t explain why, or if you sense there’s an opportunity but can’t articulate it, go back to users.

- During major redesigns or pivots. Even if you’ve been in the market for years, shifting direction merits a fresh look at user behaviour.

We’ve seen teams ignore generative work when launching a second product line, assuming they already knew their users. The result was poor adoption because the new use case had different motivations. Spending a few weeks on discovery would have saved months of engineering time.

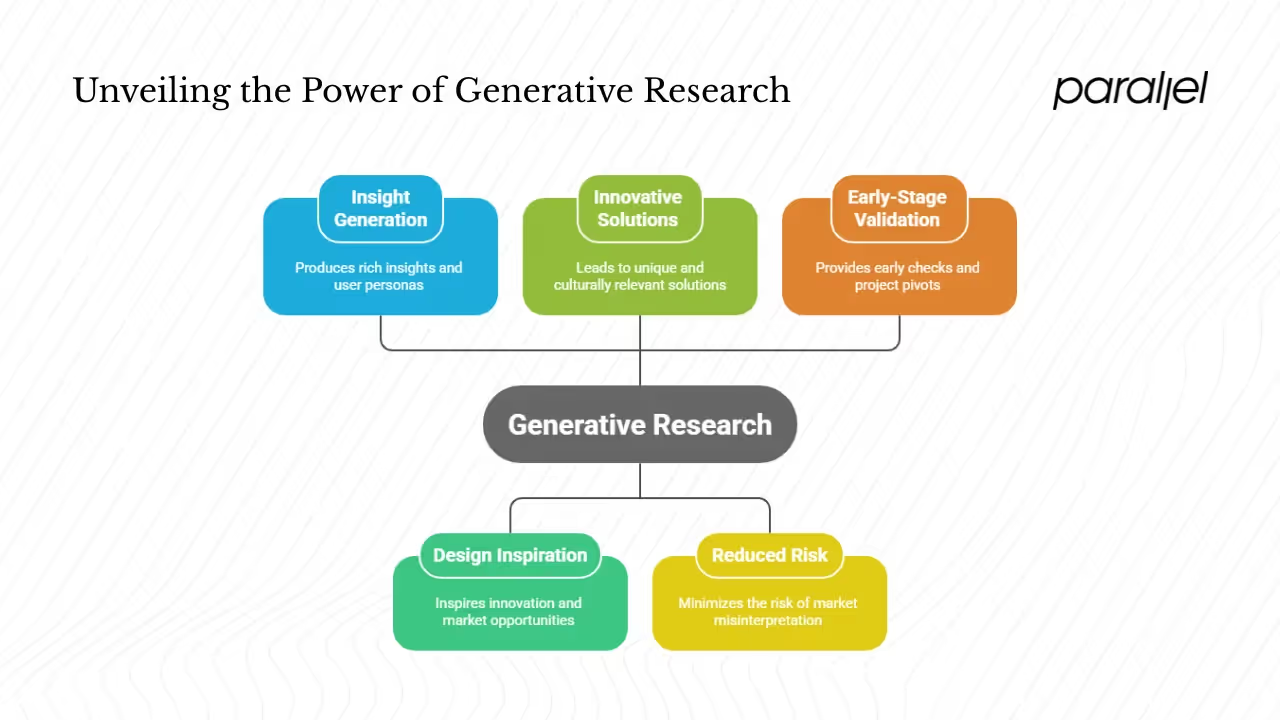

Benefits and outcomes of generative research

1) Insight generation

Generative research produces a rich set of insights. It surfaces unmet needs, mental models and behavioural patterns. Lyssna emphasises that such studies yield user personas, problem definitions and opportunity areas. These deliverables are invaluable for bringing the team together around who you’re serving and why.

2) Design inspiration

By hearing stories and seeing workarounds, you gain inspiration that goes deeper than feature requests. An Alida guide lists driving innovation and identifying market opportunities as reasons companies invest in generative research. We often convert quotes and observations into “How might we…” statements that fuel ideation sessions.

3) Innovative solutions

Because generative work opens your mind to new possibilities, it leads to solutions that stand out. In our practice we’ve learned about cultural contexts that shape product expectations, leading to design decisions that connect strongly with specific regions. Lyssna states that generative research produces new insights and opportunities for innovation.

4) Reduced risk

Investing in discovery reduces the risk of building something nobody uses. According to new company statistics, misreading market demand is the biggest reason new companies fail. Generative research guards against this by grounding your vision in reality. It also reduces the risk of accessibility and inclusivity issues, because you engage a range of people taking part.

5) Early‑stage validation

Generative work doesn’t replace evaluative research, but it does give you an early check. When you share themes and problem statements with stakeholders, they can see if those insights match their intuition. We’ve pivoted projects based on generative findings before writing a single line of code.

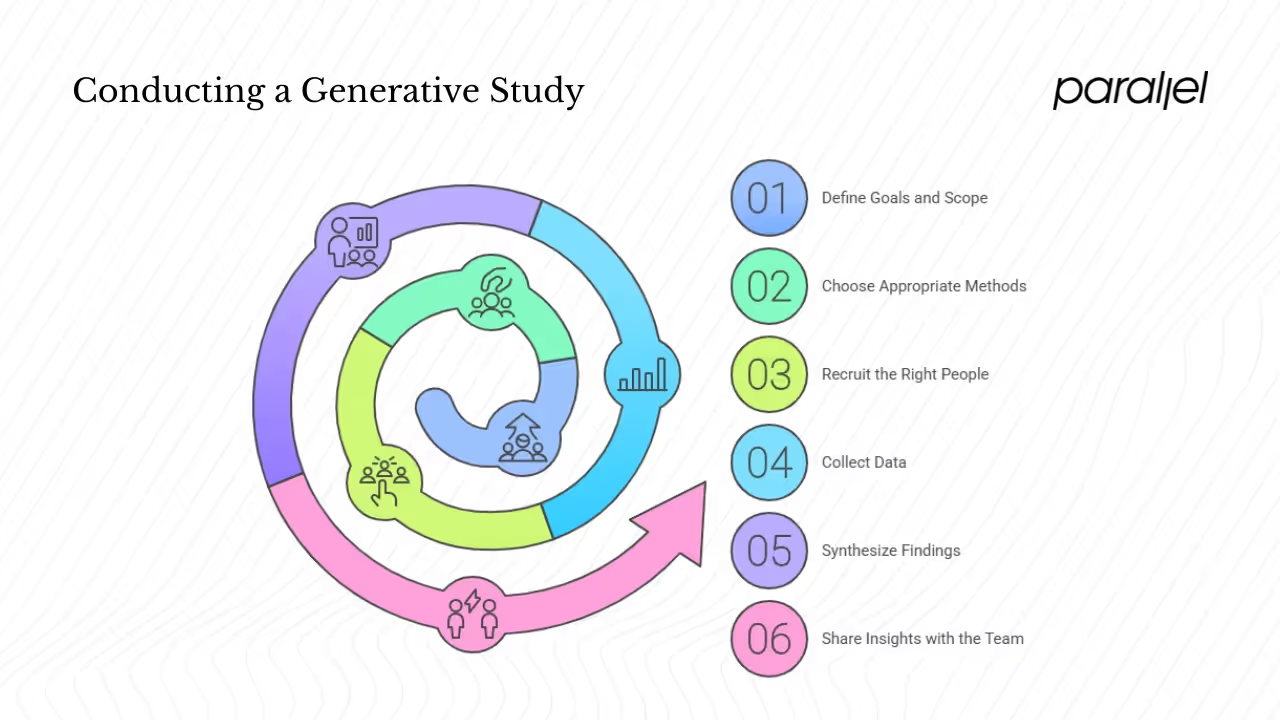

Practical steps to run a generative study

Conducting generative research doesn’t need to be complicated, but it does require planning. Here’s a process we use at Parallel.

- Define goals and scope. Collaborate with stakeholders to clarify what you hope to learn. Is it about understanding daily routines, motivations around a task, or attitudes towards a category? Alida stresses bringing the team together on the goal and making clear that you’re exploring problems, not testing solutions.

- Choose appropriate methods. Interviews are great for deep dives, diary studies capture longitudinal behaviour and workshops encourage co‑creation. Pick a mix based on your questions and timeline. Keep in mind that some methods, like field studies, require more time and resources.

- Recruit the right people. Identify who you need to talk to. For generative work, you may want both existing users and non‑users. Screen for behaviours or attitudes rather than demographics alone. At Parallel we partner with our clients’ customer success teams or use recruitment panels.

- Collect data. Record interviews (with consent) and take written observations. For diary studies, use simple check‑ins or voice memos. Observations should include sketches or photos of the environment. The more detail you capture, the easier synthesis becomes.

- Synthesize findings. Bring your team together to make sense of the data. Affinity mapping helps you group observations and quotes into themes. Look for patterns, contradictions and surprises. Summarise insights in plain language and link them to supporting evidence.

- Share insights with the team. Present the findings in a way that’s digestible and actionable. We often create one‑page posters or short videos. Including quotes and stories makes insights memorable. Connect each insight to potential opportunities for ideation.

Challenges and tips for success

Generative research is rewarding but can be tricky. Here are common pitfalls and how to avoid them.

- Vague questions and leading prompts: Asking “Do you like our idea?” will give you flattering answers. Use open questions like “Tell me about the last time you…” and let people taking part lead the conversation. Prepare thoroughly and practise your interview guide.

- Confirmation bias: Researchers often look for evidence that supports their ideas. Alida warns against introducing your hypothesis into discussions. Involve team members who weren’t part of the ideation to review data. Seek contradictory evidence and challenge assumptions.

- Lack of synthesis: It’s tempting to collect lots of data but never turn it into insights. Set aside dedicated time for analysis. Affinity mapping, experience mapping and storytelling help you turn raw observations into understanding.

- Recruiting bias: Talking only to your favourite customers yields skewed insights. Recruit a broad set of people representing different behaviours and attitudes. For generative work, talking to non‑users is invaluable.

- Balancing speed vs depth: Early‑stage teams move fast. You don’t always have months to run research. Start small: five to eight interviews can uncover major patterns. Use simple methods like quick diary check‑ins. Even a week of discovery is better than none.

Conclusion

Generative research is not a luxury reserved for large corporations. For early‑stage new companies it’s a lifeline. By asking open questions, listening deeply and observing real behaviour, you lay the groundwork for products that matter.

The data is clear: nearly half of new companies fail because they build something people don’t need. Teams that make user research a core practice see higher market share and more loyal customers. At Parallel we’ve watched small teams change after a few weeks of discovery. They went from guessing to understanding, from shipping features to solving problems.

If you’re a founder, product manager or design leader, make generative research part of your playbook. Integrate it early and revisit it regularly. You’ll not only reduce risk but also uncover opportunities that lead to meaningful innovation. Your customers deserve it—and so does your team.

FAQs

1) What does generative research mean?

Generative research is a user research method focused on uncovering needs, motivations and behaviours before a solution exists. It generates insights that inspire new ideas.

2) What is a generative approach to research?

A generative approach is proactive and exploratory. It prioritises open‑ended discovery over validating an existing idea. You engage people taking part in interviews, observations, diary studies and workshops to find problems and opportunities.

3) What are examples of generative user research?

Examples include in‑depth interviews, ethnographic field studies, diary studies, card sorting, co‑creation workshops and open‑ended surveys. Observations and user interviews are often the most accessible methods.

4) What is the difference between generative and foundational research?

Foundational research looks broadly at markets or user segments to build a strategic understanding, while generative research dives into specific behaviours and motivations to generate product ideas. Both happen before design and inform strategy, but generative studies produce concrete problem statements and ideas for solutions.

.avif)