What Is Lean UX? Complete Guide (2026)

Explore lean UX principles, focusing on collaborative design, rapid experimentation, and iterative improvements to deliver user value.

Building a product is hard. In the rush to get to market, early‑stage teams often waste months designing features no one wants, writing specifications that read like novels and operating in separate silos. I see teams in the machine‑learning and software space pour time into pixel‑perfect interfaces only to scrap them when user feedback arrives too late.

In 2025, research shows that about 34% of startups fail because they have poor product–market fit—in other words, they build the wrong thing. Many founders ask what lean ux is and whether it can help them avoid this fate.

This guide explains what Lean UX is, how it differs from traditional UX, why it matters for startups, how to put it into practice and the pitfalls to watch out for. I’ll speak from both research and lived experience, with the goal of helping founders, product managers and design leaders work smarter.

What is Lean UX?

Lean UX is a user‑centered approach that stems from agile principles. Unlike traditional UX methods that rely on detailed documentation and long research phases, Lean UX is an iterative and collaborative process. The goal is to reduce waste, test assumptions quickly and build a shared understanding across design and development.

As Jeff Gothelf and Josh Seiden define it, Lean UX is “inspired by Lean Startup and Agile development” and is about bringing the true nature of a product to light faster in a collaborative, cross‑functional way. Teams working this way prioritise learning over delivery, using rapid prototypes and real user feedback to inform decisions. Instead of producing thick design documents, they create only the minimal deliverables needed to move learning forward.

Lean UX has its roots in lean manufacturing and the agile software movement. Lean manufacturing focused on removing waste and continuously improving production processes. Agile took those ideas and applied them to software delivery. Lean UX adapts them further for the user experience field: work in small batches, validate with users early and often, and collaborate across functions. In practice that means product managers, designers and engineers work together from the start to define problems, test hypotheses and iterate quickly. The result is a product informed by real customer needs rather than internal assumptions.

Lean UX versus traditional UX

Principles and mindset

Lean UX rests on a handful of ideas. User‑centered design means making assumptions explicit and grounding decisions in real customer needs. Iterative learning is the build‑measure‑learn cycle: produce small increments, measure impact and adjust. Efficiency in design calls for minimal artifacts—quick sketches or prototypes that teach something new. Experimentation gives teams permission to try and fail; not every idea will work and that is fine. Continuous improvement ensures that both the product and the process get better over time. Adopting these principles demands trust and a willingness to be wrong, but it yields momentum and products that serve users better.

The Lean UX process: think, make and check

If you still wonder what lean ux is in practice, Lean UX unfolds in loops of thinking, making and checking. In the think phase, the team clarifies the problem, states assumptions and decides how to measure success. Research is deliberately lightweight; interviews and data analysis are meant to build a shared understanding, not produce a tome.

Make is about building the minimum thing needed to test a hypothesis—this could be a paper sketch, a clickable prototype or even a live “fake door”. Speed matters more than polish: the point is to put something in front of users quickly.

Check involves showing that prototype to real users and gathering feedback through usability tests, surveys or analytics. Based on what you learn, you decide whether to invest more, iterate or pivot. These loops can run in days rather than weeks and scale up or down with team size.

Why Lean UX matters for startups

For founders and product managers operating under tight constraints, Lean UX offers a way to avoid building the wrong product. Startups typically face three challenges: limited time, limited money and uncertainty about the problem to solve. Traditional UX with its long research and design phases can be risky. Lean UX addresses those challenges by placing small bets and learning quickly. Teams avoid big investments in features nobody will use. This is important because a lack of product–market fit is behind about one‑third of startup failures. In my own work with machine‑learning‑driven SaaS teams, simple prototypes have shown surprising insights and saved months of development. The same approach helped the scheduling tool Doodle refine a single page and increase trial signups by 25%.

Lean UX also improves collaboration and focus. When designers, engineers and product managers work together from day one, there is no “throw it over the wall” moment. Meetings become about outcomes rather than deliverables, and decisions are grounded in shared evidence. This shared understanding speeds development and keeps the team aligned around customer problems rather than investor‑driven feature lists.

Tools and techniques

When you look up what lean ux is, you might think there’s a single toolkit, but it’s more about how you work than what you use. Lean UX isn’t tied to a specific toolset. Lightweight sketches, Figma prototypes, wireframes or quick landing pages are enough to test an idea. Feedback comes from interviews, guerilla usability tests, surveys and analytics; qualitative methods reveal why users behave a certain way and quantitative data shows what happens. When you have many ideas competing for attention, frameworks like Impact–Certainty–Effort (ICE) help prioritise them. Use simple metrics to decide if a hypothesis holds. Keep rituals like short workshops to declare assumptions, regular check‑ins to share learnings and lightweight documentation to record what was learned. The point is to focus on learning rather than perfect deliverables.

Challenges and pitfalls

Adopting Lean UX can still be challenging. Some stakeholders expect detailed roadmaps and documentation; they might feel uneasy about working with rough prototypes. Clear communication about the process and its benefits—and showing quick wins—can build trust. Teams must also avoid vanity metrics by tying measures directly to hypotheses: if the hypothesis concerns abandoned carts, measure checkout completion, not page views. Rapid cycles may lead to endless tweaking without a goal; guard against this by defining success criteria and moving on if an experiment fails. Working fast doesn’t mean skipping research: talking to users is non‑negotiable. Finally, Lean UX only works when designers, developers and product managers share ownership of outcomes; if they operate in silos, the approach falls apart.

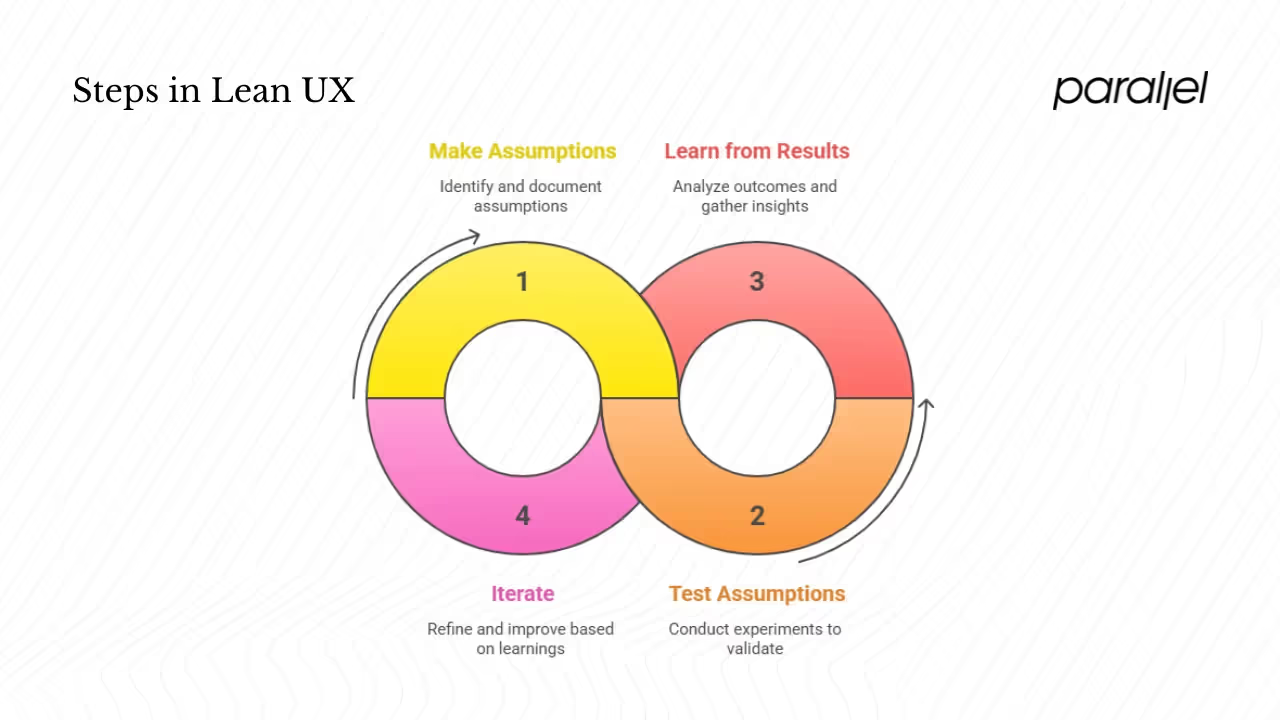

How many steps are in Lean UX?

When people ask how many steps are in what is lean ux, they’re often looking for a recipe. In truth, the number of steps varies. Many teams use the three‑phase Think–Make–Check loop. Others adopt more granular models like the five steps UXTweak lists: assumptions, hypotheses, design and prototype, run experiments, and learn and iterate. The Lean UX Canvas, a tool popularised by Jeff Gothelf, adds structure around user, business and solution assumptions. The lesson is that Lean UX is flexible. You and your team can break the process into whatever steps make sense for your context and benefit from making assumptions visible, testing them quickly and learning from the results.

Smaller teams may collapse steps together—for example, running experiments while prototyping. Larger organisations may separate roles for research, design and development but still work in short loops. Use the framework that keeps the feedback cycle tight. The point isn’t to follow a rigid recipe, but to embed learning and collaboration into your work.

Is Lean UX safe?

Lean UX reduces business risk by validating ideas early. By testing small pieces with users, you learn whether an idea holds water before investing heavily. But it isn’t suitable everywhere. Products in regulated industries such as medicine, finance and aviation require detailed documentation and must meet strict standards. Those constraints do not preclude lean thinking; you can still collaborate closely, test prototypes internally and gather early feedback. You just need to integrate these experiments with compliance processes and protect user data. When in doubt, run design reviews and ethical checks, roll out changes in small increments and involve legal and privacy experts to ensure you balance agility with due diligence.

Conclusion

At its heart, what is lean ux is a shift from outputs to outcomes. It asks us to stop obsessing over deliverables and start asking whether we are solving the right problem. Lean UX emphasises collaboration, rapid iteration, user‑centered design and continuous improvement. For startups, adopting this mindset can mean the difference between burning capital on unused features and building a product that customers love.

I encourage founders and product leaders to run a pilot: pick a small problem, create a cross‑functional team, declare your assumptions and design a quick experiment. Keep the materials light, measure real user behaviour and let the evidence guide you. This small start can change how you build products. If you want to learn more, read Jeff Gothelf and Josh Seiden’s Lean UX and consider hosting a hypothesis workshop with your team. If you’re unsure how to begin, start by mapping your assumptions and inviting your team to run a small experiment—you might be surprised by what you learn. By now you should have a clear sense of what is lean ux and how it can help you. The sooner you shift from guessing to learning, the sooner you’ll build something people will pay for.

FAQ

1) What is a Lean UX approach?

A Lean UX approach combines agile methods, lean thinking and user‑centered design. Teams work in short cycles, create simple prototypes, test them with users and learn from the results.

2) What is the difference between UX and Lean UX?

Traditional UX often means long research phases and detailed specifications. Lean UX focuses on quick cycles of building and testing, cross‑functional collaboration and learning over delivery.

3) How many steps are there in Lean UX?

There is no single answer. Teams often use a three‑phase Think–Make–Check loop; others break it into five steps. What matters is making assumptions explicit, testing them and learning quickly.

4) Is Lean UX safe?

Lean UX reduces risk by validating ideas early, but regulated sectors such as medicine and finance require detailed approvals and documentation. In those cases adapt Lean UX to fit compliance needs and protect user privacy.

.avif)