What Makes a Good Product Manager? Guide (2026)

Discover the qualities and skills that define a successful product manager, including leadership, communication, and strategic thinking.

The best product stories are about people who learn and adapt. Early in my career I saw a founding product manager break a feature factory cycle by listening to users and pushing for change despite having no formal authority. When she left, the team slid back into chasing requests. Her story shows how crucial certain traits are in startups, where product sits between vision and execution. Knowing what makes a good product manager helps founders, leaders and early‑stage teams shape hiring, strategy and personal growth. We'll examine the qualities, habits, pitfalls and development paths that define effective product leadership.

TL;DR: What Makes a Good Product Manager?

A good product manager combines user empathy, strategic vision, communication skills, analytical thinking, and leadership to deliver valuable, user-centered solutions. They balance near-term execution with long-term planning, make data-informed decisions, lead through influence, and adapt to fast-changing environments. Key traits include problem-solving, prioritization, market awareness, technical fluency, and the ability to say “no” tactfully. Great product managers also focus on outcomes over outputs, practice continuous discovery, involve cross-functional teams, and constantly seek feedback to improve. Context—like company stage or industry—shapes how these skills apply.

Core qualities of a good product manager

A product manager at an early‑stage company is a strategist, translator and diplomat. They draw on a mix of empathy, analysis, strategy and leadership to connect user needs with business goals. Understanding these core qualities explains what makes a good product manager in fast‑moving environments. These qualities create a foundation for success.

1) User‑centric mindset and empathy

Great products start with a deep understanding of users. Being user‑centred means listening to people’s needs and pains, even when those pains are not voiced directly. In a survey of 52 product managers, the word “empathy” appeared more than ten times, and respondents emphasised that soft skills mattered more than technical skills. One respondent summarised it well: a product manager must “understand that their empathy for their users’ emotions must exceed all logic and data”. Empathy isn't guesswork; it is built through interviews, observation and usage data. Product managers can practice perspective‑taking, volunteer with different communities and bring users into early conversations to strengthen this skill. At Parallel we often watch users struggle with early prototypes; those sessions reveal unspoken friction points that no analytics dashboard can show.

2) Communication skills

Much of the work in product is communication. The job involves translating between founders, engineers, designers and customers. Leland’s 2025 skills guide points out that product managers serve as a bridge across engineering, design, marketing and sales, and they must ensure that the product serves both user needs and company goals. Clear verbal and written communication builds trust, reduces confusion and keeps momentum. Good communicators also listen actively, adjust their message to each audience and use stories to explain why a decision was made. On one client project we realised our roadmaps read like a backlog of tasks rather than a narrative. We changed the framing to outcomes and saw engagement from leadership soar.

3) Problem‑solving and analytical ability

Product work is filled with open‑ended questions. Defining the right problem before proposing solutions requires curiosity and rigorous analysis. A 2024 ProductPlan survey found that prioritisation decisions are driven first by customer needs and wants, followed closely by company goals. That order reflects how great product managers think: they frame problems in terms of user and business value, then use data to test assumptions. Analytical skills include reading metrics, designing experiments and weighing trade‑offs. When we built a machine‑learning‑powered onboarding flow, our first version asked users to supply multiple data points. Usage data showed high drop‑off, so we ran an A/B test with a simplified sign‑up flow and cut abandonment by 30 %. Without analysing real behaviour, we might have rationalised the drop‑off as poor marketing rather than a solvable design issue.

4) Strategic and visionary thinking

Startups live in the future while acting in the present. A product manager needs to balance near‑term execution with long‑term vision. Product School describes strategic thinking as developing a long‑term vision that guides product evolution and sets clear goals that match broader business objectives. Visionary thinking goes a step further by anticipating market shifts and betting on emerging trends. At the same time, a strategy should be adaptable; as the Nielsen Norman Group warns, technology is changing quickly and those who cling too tightly to past practices risk irrelevance. A good product manager looks up from the backlog and asks, “Where do we need to be in two years, and how do today’s choices support or hinder that?”

5) Technical knowledge

Product managers don't need to be coders, but technical fluency allows them to engage meaningfully with engineers and understand constraints. Product School points out that writing technical requirements and understanding how systems are put together enhances collaboration and innovation. Technical understanding helps with scoping, estimating and making informed trade‑offs. In early‑stage machine learning and SaaS teams, we’ve seen product managers succeed when they can explain why a machine‑learning model’s inference time will slow the user experience or why a microservice architecture might delay a feature. Those details build credibility with engineering colleagues and prevent unrealistic commitments.

6) Leadership and collaborative ability

Product managers lead through influence rather than authority. They inspire teams, negotiate with stakeholders and create a space where different disciplines can contribute. The Nielsen Norman Group emphasises the importance of empathising with other disciplines and building partnerships. In practice, that means explaining ideas in plain language, adapting processes to meet teams midway and staying focused on shared outcomes. We once worked with a startup where the design team felt sidelined; the product manager held a workshop to co‑create the roadmap and invited feedback on trade‑offs. The resulting trust improved speed and morale.

7) Prioritisation skills and time management

Managing trade‑offs is one of the most tangible skills in product management. The 2024 ProductPlan report shows that customer needs and company goals are the top drivers of prioritisation, while other factors such as internal requests and competition rank lower. Great product managers weigh effort against impact, decide what to postpone and organise their own time. They use frameworks like RICE (reach, impact, confidence, effort) to compare initiatives and consider both data and instinct. They also shield teams from constant context switching by sticking to the plan unless new information warrants a pivot.

8) Adaptability and resilience

Startups are unpredictable. Plans change when user feedback or market conditions shift. Adaptability means adjusting course without losing sight of the bigger goal. The Nielsen Norman Group encourages professionals to be flexible and resourceful, particularly as emerging technologies such as machine learning change the work. Resilience complements adaptability; it is the ability to stay calm during uncertainty, learn from failures and keep moving. When our team’s first attempt at a machine‑learning feature failed due to data quality issues, the product manager kept morale high, iterated quickly and eventually delivered a simpler rule‑based solution that met user needs.

9) Market awareness

Understanding the competitive environment and domain trends helps product managers make informed bets. Market sensitivity involves analysing competitors, tracking adjacent industries and recognising shifts in user expectations. Product School suggests subscribing to industry newsletters and conducting competitor analysis to stay attuned to market forces. For a fintech client, staying aware of regulatory updates helped us design features that complied with local laws while still offering a smooth experience for small businesses.

10) Decision‑making

Product managers often decide with incomplete information. Being decisive, taking responsibility and communicating rationale are crucial. The ProductPlan report found that in small companies, CEOs control prioritisation decisions 43 % of the time, whereas only 38 % see product managers owning decisions. In medium and large companies, product leaders have more control. Regardless of the structure, a product manager’s value lies in synthesising input, weighing risks and committing to a course. Decisiveness builds momentum and clarifies accountability.

Behaviours and habits of highly effective product managers

Qualities become useful when they shape daily work. Effective product managers cultivate habits that translate qualities into outcomes. These behaviours show what makes a good product manager stand out from someone who merely manages tasks.

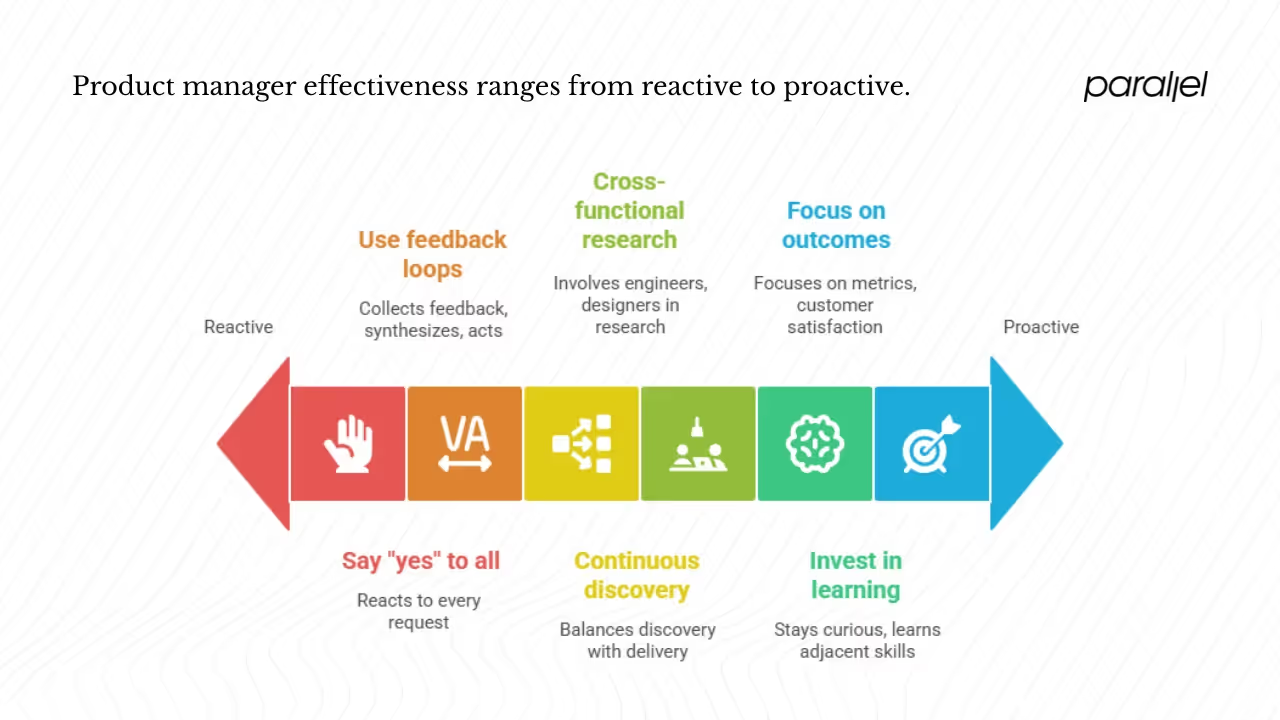

- Focus on outcomes over outputs: Rather than counting features shipped, focus on metrics that matter—customer satisfaction, retention or revenue. This outcome mindset is gaining traction in the design community. The Nielsen Norman Group advocates an outcome‑oriented approach to design and warns that building features for the sake of machine learning hype seldom works.

- Continuous discovery: Discovery isn’t a one‑time phase; it is ongoing. According to the 2024 ProductPlan report, only 17 % of respondents spend most of their time on discovery while 39 % focus mostly on delivery. Balancing discovery with delivery increases the odds that what you build solves real problems. Great product managers schedule regular user interviews, run experiments and adjust roadmaps based on findings.

- Cross‑functional research: A 2025 survey found that 73.3 % of teams involve a product manager in user research, 45.2 % involve a product designer and 27.8 % involve a tech lead. Yet only 19.1 % of teams have the full trio of product manager, designer and engineer in discovery. Effective managers invite engineers and designers into research to build shared understanding, leading to better solutions.

- Use feedback loops wisely: The same 2025 report observed that the percentage of teams using a specific repository for user feedback rose from 36.6 % to 46.6% between 2024 and 2025. Storing feedback separately from the backlog prevents teams from chasing every request and allows them to identify patterns. Good product managers set up processes for collecting, synthesising and acting on feedback without being reactive.

- Say “no” tactfully: Prioritisation means declining features that don’t advance the strategy. The ProductPlan survey shows that customer needs and company goals should guide priority. When stakeholders propose work that doesn’t meet those criteria, a polite “not now” protects focus. Good product managers explain the reasoning and offer alternative paths when appropriate.

- Invest in learning: The field changes quickly, so staying curious matters. Read case studies, attend webinars and learn adjacent skills such as UX research or basic machine learning. A poll by the Nielsen Norman Group showed that 84 % of UX professionals value creating impact as the best part of their job. That drive for impact fuels ongoing learning.

Differences between good and great product managers

All good product managers share the qualities above, but the ones who stand out do a few things differently. This section examines how those differences build upon what makes a good product manager and raise them to exceptional.

Common pitfalls and signs of a poor product manager

Understanding what not to do can sharpen understanding of what makes a good product manager. Some common pitfalls include:

- Lack of user insight. Building features without validating user needs leads to wasted effort. When product strategy is dictated by senior leadership, fewer product people spend time in discovery, leading to feature factories.

- Saying yes to everything. Without clear prioritisation, the backlog becomes bloated. The ProductPlan survey indicates that prioritisation should be guided by customer needs and company goals Saying yes to every request dilutes impact.

- Poor communication. Keeping stakeholders in the dark erodes trust. A good product manager shares context, progress and decisions. Silence invites confusion.

- Indecisiveness. Delaying decisions stalls progress. If you wait for perfect data, competitors move faster. It’s better to make a call, test it and adjust than to spin in analysis.

- Being too tactical or too strategic. Focusing only on delivery without a vision leads to reactive development, while staying in the clouds without execution frustrates teams. Balance is vital.

- Ignoring feedback or data. Sticking to a plan despite evidence to the contrary shows ego over impact. Good product managers adapt when user feedback or metrics reveal a wrong direction.

How to develop these skills (for founders, early PMs and leaders)

No one starts with all these abilities. Growth comes from deliberate practice. If you want to embody what makes a good product manager, you need to put in the work.

- Assess yourself. List your strengths and gaps across the qualities above. Are you strong in analysis but weak in storytelling? Awareness guides improvement.

- Seek feedback. Ask team members, users and mentors for honest perspectives. Peer reviews or 360‑degree evaluations expose blind spots.

- Shadow and mentor. Observe experienced product managers in action and find a mentor. Conversely, mentor someone less experienced to sharpen your own thinking.

- Get hands‑on. Lead discovery sessions, write a product requirements document or run a metrics review. Doing the work embeds lessons.

- Study cases and books. Read research like the ProductPlan and Thingsters reports for data‑driven insights. Books like Inspired by Marty Cagan and articles by thought leaders provide frameworks.

- Experiment and iterate. Build small features or prototypes, collect feedback and adjust. Practising rapid iteration teaches adaptability.

- Use prioritisation frameworks. Tools like RICE and MoSCoW help structure trade‑off decisions. Pick one and apply it consistently.

- Improve time management. Use calendars, to‑do lists and focus blocks. Scheduling discovery sessions alongside delivery tasks ensures neither gets neglected.

Context matters: stage, domain and team size

What makes a good product manager changes with context. The answer varies across stages and industries.

- Early‑stage startups. Resources are scarce and roles blur. Product managers at this stage must be generalists, comfortable wearing multiple hats. Because there may be no dedicated designer or researcher, the product manager often gathers user feedback themselves. Decision‑making cycles are quick, and there is little room for structured processes.

- Scale‑ups and larger organisations. As companies grow, roles specialise. Product managers can focus on strategy while relying on design and engineering leads for execution. They must coordinate across teams and balance autonomy with cohesion. In medium and large companies, product managers are more likely to control priority decisions.

- Consumer vs. enterprise products. Consumer products emphasise ease of use, virality and emotional resonance. Enterprise products require deep domain knowledge, integration with existing systems and navigation of longer sales cycles. The product manager’s focus shifts accordingly.

- Regulated domains. In healthcare or finance, compliance shapes product decisions. Understanding regulations becomes part of the job. Market awareness includes monitoring policy changes.

- Technical vs. non‑technical founding teams. When founders are technical, product managers may need to champion user research and link the product to business goals. When founders are non‑technical, product managers might lean into scoping and feasibility.

Conclusion

So, what makes a good product manager? It’s not a single trait but a combination of empathy, clear communication, analytical rigour, strategic thinking, technical fluency, leadership, prioritisation, adaptability, market awareness and decisive action. When these qualities show up in daily habits—focusing on outcomes, practising continuous discovery, involving cross‑functional teams, managing feedback wisely and learning constantly—good becomes great. The role is context‑dependent, and there’s no perfect template. Yet by cultivating these skills and behaviours, staying curious, and balancing vision with execution, product managers at early‑stage startups can guide teams through uncertainty toward products that users love and businesses value. Growth is not accidental; it’s the result of deliberate practice, reflection and a relentless focus on creating real value.

FAQs

1) What are the 5 C’s of product management?

They are customer, collaboration, communication, curiosity and commercial sense. Customer refers to understanding user needs deeply. Collaboration means working across functions. Communication covers clear dialogue and storytelling. Curiosity drives discovery and learning. Commercial sense ensures that the product supports the business.

2) What are the 5 P’s of product management?

They typically stand for product, problem, people, process and profit. Product is the solution you’re building. Problem reminds you to define what you’re solving. People include users and team members. Process covers how you deliver and learn. Profit emphasises sustainability.

3) What is the most critical skill for a product manager?

There is no single silver bullet, but empathy comes close. The Medium survey of 52 product managers found that empathy was the most mentioned trait, and Product School describes it as a cornerstone of user‑centred design. Without empathy, it’s difficult to prioritise effectively, communicate clearly or make decisions that serve users and the business.

4) What is the profile of a bad product manager?

A poor product manager avoids user research, says yes to every request, communicates poorly, hesitates to decide, focuses either only on tactical tasks or only on vision, and ignores feedback. They may also impose ideas without listening to engineers or designers, leading to friction and missed opportunities.

.avif)