What Is Market Validation? Complete Guide (2026)

Explore the concept of market validation, why it’s critical for startups, and methods for testing whether customers want your product.

In 2008, Drew Houston and Arash Ferdowsi had a clever hack: before they wrote any code for their file‑sync idea, they published a three‑minute video that explained what the service would do. Within 24 hours, more than 70 thousand people joined the waiting list. That wave of sign‑ups didn’t just stroke their egos—it convinced them that a real problem existed and investors should take the bet. Contrast that with Juicero, a venture‑backed juicer that spent $120 million building a sleek machine only to discover that most people didn’t need a $400 Wi‑Fi connected juicer. One team validated demand up front; the other relied on optimism and failed. Those stories illustrate what market validation is and why it matters.

What Is Market Validation? A Simple Explanation

Market validation is the process of testing whether real people in your target audience are willing to engage with or pay for your product idea—before you build it. It turns assumptions into evidence using experiments like landing pages, interviews, prototypes, or paid pilots. If nobody signs up or pays, you’ve learned something valuable without wasting months of work.

What is market validation?

At its core, market validation is the practice of presenting an idea to the people you hope will buy it and gathering evidence about whether they care. It comes after broad research and before building a full product. In our work with AI and SaaS founders at Parallel, we see too many teams confuse internal enthusiasm or investor interest with proof of demand. As Thinslices’ research warns, “every startup begins with a hypothesis, but you haven’t validated anything until someone outside your team cares enough to engage—sign up, pay or even just respond”.

Validation isn’t a substitute for customer research; it’s a filter that turns assumptions into evidence. When you validate early:

- You minimise waste: CB Insights analysed over 100 startup post‑mortems and found that no market need causes 35 percent of failure. A 2025 report notes that 34 percent of small businesses that fail lack product–market fit.

- You increase investor confidence: venture studios like 25Madison emphasize that early market validation is “the crucial first step that separates successful founders from those who spend months building products nobody wants”. Concrete evidence—sign‑ups, wait‑lists, paid pilots—signals to investors that the problem is real.

- You refine direction sooner: by testing messages, prototypes or pricing, you avoid building the wrong thing. According to the Nielsen Norman Group, “status feedback is crucial to the success of any system”; staying close to your audience ensures you always know whether you’re on track.

Where it fits: Idea → Validation → MVP → Scaling. In lean and agile environments, every concept is treated as a testable assumption. You don’t need to wait for a polished product; you can validate with landing pages, interviews or even a “Wizard of Oz” prototype where a human pretends to be the software.

Core concepts and supporting terms

Understanding what is market validation requires clarity around related concepts. These terms often get blended together but serve distinct purposes.

Customer feedback and feedback loops

- Qualitative vs quantitative: Talking to users uncovers motivations and pain points; measuring click‑throughs or sign‑ups shows whether behaviour matches words. A healthy validation process blends both.

- Feedback loops: Nielsen Norman Group notes that systems must “keep users informed” and provide clear feedback. Likewise, validation is iterative: you present an offer, collect reactions and adjust.

Target audience analysis

- Segmentation: define buyer and user personas by demographics, behaviours and psychographics. 25Madison advises founders to create specific, measurable hypotheses—for example, “manufacturing plant managers need predictive software to reduce downtime by 20%”. Vague hypotheses produce vague validation.

- Problem–solution fit: early interviews reveal whether the problem hurts enough to inspire action. As 25Madison points out, direct conversations remain “the gold standard” for early validation.

Market demand and trend signals

Look beyond your bubble. Secondary research (industry reports, search trends) hints at emerging opportunities. But be wary of hype; as we saw with generative AI, interest alone isn’t validation. Trend data should guide questions, not serve as proof.

Competitive analysis

Mapping competitors reveals gaps. Observing their pricing, traction and user reviews gives indirect signals of demand. If incumbents are hiring aggressively or raising capital, there’s likely a market—but that doesn’t mean there’s room for your twist. Validation ensures your differentiator is meaningful.

Product–market fit (PMF)

Marc Andreessen famously described PMF as “being in a good market with a product that satisfies that market.” Validation is the stepping stone toward PMF. It helps you test whether your value proposition resonates before investing heavily. When metrics like retention, usage frequency and referrals tick up, you’re closer to PMF.

Prototypes, MVPs and fake doors

- Low‑fidelity prototypes: sketches, clickable wireframes or simple videos. Lyssna’s concept testing guide notes that early‑stage ideas benefit from simple monadic tests.

- Fake‑door tests: a landing page or call‑to‑action collects sign‑ups for a non‑existent feature. Thinslices suggests a 10% conversion rate as a benchmark; anything lower signals that your messaging, audience or core idea needs revision.

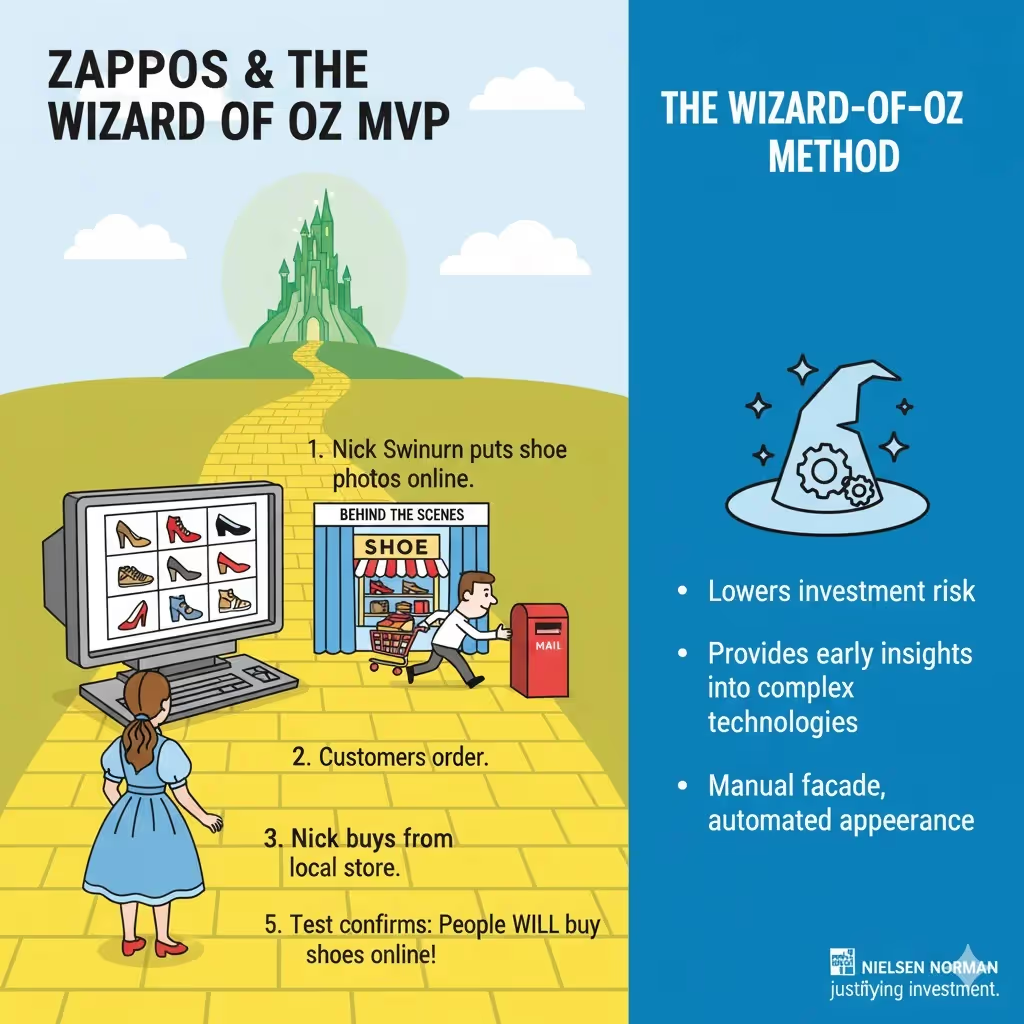

- Wizard of Oz / Concierge MVP: Nielsen Norman Group explains that the Wizard of Oz method lets a user interact with an interface that appears autonomous but is actually controlled by a human. This low‑cost approach delivers early insights into desirability and usability before investing in complex technology. Zappos famously fulfilled orders manually to prove that people would buy shoes online. In a concierge MVP, there’s no illusion—you manually deliver the service and learn from every interaction.

Sales data validation

Ultimately, the strongest signal is someone paying for your solution. Pre‑orders, pilot contracts and paid pilots reveal willingness to pay. 25Madison argues that a handful of paying customers is far more valuable than hundreds of free users.

Validation metrics

Common metrics include:

- Sign‑up rate / conversion rate: For landing pages, Thinslices uses 10% as a rule of thumb.

- Click‑through rate on ads or emails: measures curiosity.

- Net Promoter Score (NPS): indicates how likely users are to recommend your concept.

- Retention / repeat purchase: early pilot customers who stick around are gold.

- Qualitative enthusiasm: excitement and willingness to refer others matter more than polite compliments.

How to conduct market validation

1. Start with hypotheses

Write down assumptions about the problem, audience, solution and business model. 25Madison emphasises that a precise hypothesis—who experiences the problem, why they’ll pay and how much—makes validation meaningful. Ambiguity leads to ambiguous results.

2. Define your audience & segmentation

Identify target segments and personas. Use LinkedIn, forums or your network to recruit 10–12 people who match those profiles. Don’t rely on friends; you need unbiased perspectives.

3. Choose your validation methods

There’s no single path; pick the method that matches your stage and risk level.

Problem/solution interviews & surveys

Conduct open‑ended interviews to understand current pain points, existing solutions and willingness to pay. Surveys can scale this but lack nuance. In interviews, listen more than you talk and look for emotional reactions.

Landing page / fake‑door test

Create a simple page explaining your value proposition with one call‑to‑action. Use tools like Webflow or Carrd. Drive targeted traffic through small ad spends or community posts. Track sign‑ups, time on page and heatmaps. If conversion is below 10%, revisit your message or audience.

Prototype / concept testing

Use low‑fidelity prototypes (mock‑ups, videos) or moderated studies. Lyssna’s 2025 guide defines concept testing as collecting feedback on a concept during the product testing phase, after ideation but before development. It recommends combining qualitative and quantitative data, selecting participants carefully and choosing the right test type based on product maturity. Concept testing reduces financial risk: fixing an issue after release can cost up to 100 times more than addressing it during early design stages.

Minimum viable product (MVP) / pilot

Build only enough to test your core value proposition. A “single‑feature MVP” focuses on one problem. High‑fidelity MVPs like Wizard of Oz or concierge MVPs let you mimic the product while doing the work manually. Pre‑orders and crowdfunding campaigns generate revenue and validate demand before building.

A/B testing & experiments

Once you have traffic, test different value propositions, pricing tiers or features to see what resonates. Use these experiments to refine your messaging and offering.

Usage analytics

When you have a live prototype or beta, track how people use it: Which features they try first, where they drop off and how often they return. Retention and engagement indicate whether you’re solving a real problem.

Competitive validation & secondary data

Observe competitors’ traction, job postings and customer reviews. Use industry reports, search trends and market forecasts to gauge whether the problem is growing. But treat these as directional; only real user behaviour validates your hypothesis.

Hybrid / multi‑method validation

Combine qualitative and quantitative methods. For example, run interviews to understand why people sign up, then iterate messaging on your landing page and measure conversion. This triangulation reduces bias.

4. Launch small experiments and gather data

Run your chosen tests quickly and cheaply. Resist the urge to polish; early feedback on a rough prototype can save months of engineering.

5. Analyse & derive insights

Don’t cherry‑pick vanity metrics. Focus on behaviour, not just opinions. If people say they love your idea but don’t sign up or pay, their words are meaningless. Use thresholds (e.g., 10% conversion, 30% willingness to pay) to decide whether to proceed, pivot or scrap the idea. Document what you learned for future decisions.

6. Iterate, pivot or proceed

Validation is iterative. If results are weak, adjust your hypothesis, target audience or value proposition. If signals are strong—people are signing up, paying or referring others—move forward to building and scaling. If evidence suggests there’s no real problem, have the discipline to walk away. It’s better to pivot early than burn resources.

Examples and case studies

Dropbox: fake door success

Dropbox’s founders didn’t build a product until they had proof of demand. A simple video explained the concept; within a day 70 thousand people signed up. This “fake‑door” test validated that their idea solved a pain point and gave them leverage with investors. The tactic is still relevant: in our own work, we’ve run similar video demos for internal AI tools and measured whether prospects request early access before writing code.

Zappos & the Wizard of Oz MVP

Before investing in warehouses or automation, Nick Swinmurn put photos of shoes online. When customers ordered, he went to a local store, bought the shoes and mailed them. From the outside, shoppers experienced an online store; behind the scenes, it was manual. The test confirmed that people would buy shoes on the internet, justifying investment. This is the essence of the Wizard‑of‑Oz method, which Nielsen Norman Group says lowers investment risk by providing early insights into complex technologies.

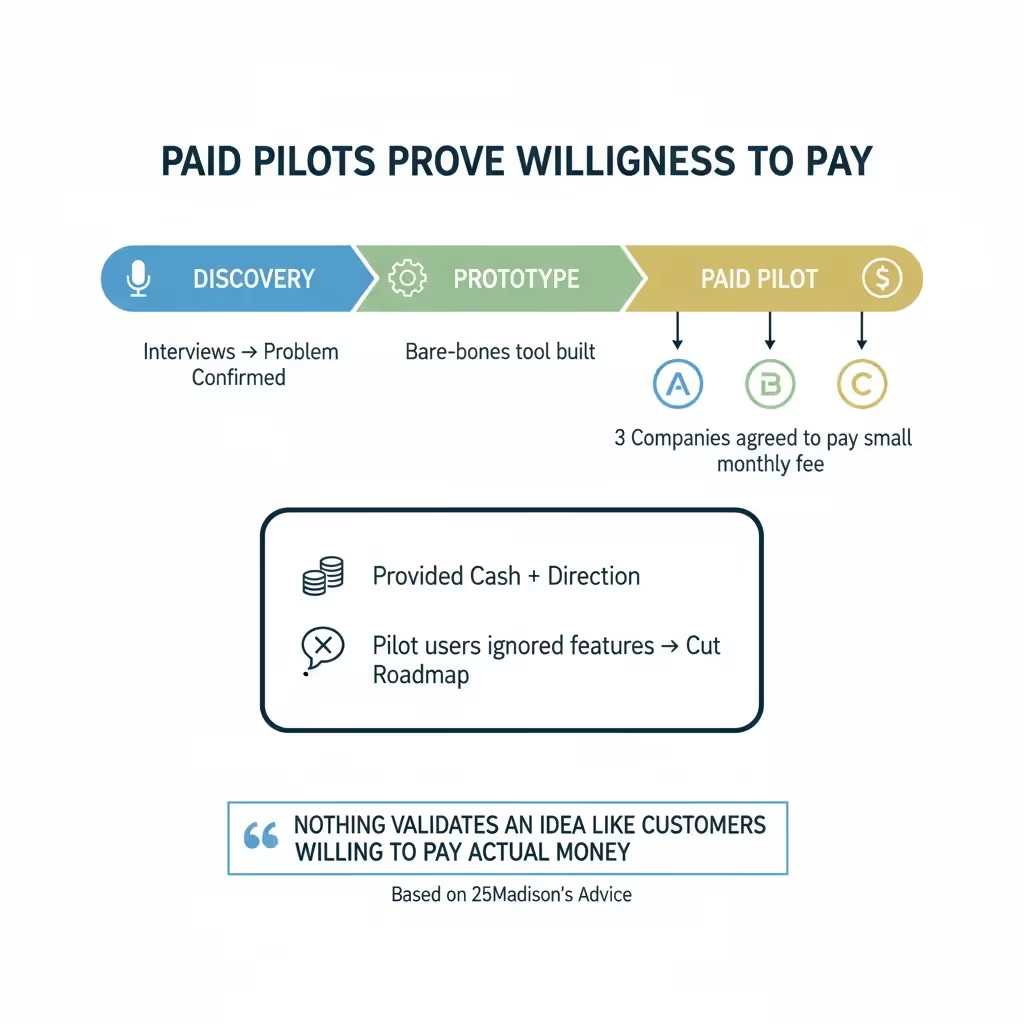

Paid pilots prove willingness to pay

In one recent Parallel project, we helped a B2B SaaS founder test an AI‑powered workflow tool. After a handful of discovery interviews confirmed the problem, we built a bare‑bones prototype and invited prospects to a paid pilot. Three companies agreed to pay a small monthly fee in exchange for influence over the roadmap. Their engagement provided both cash and direction; features that seemed exciting internally were cut when pilot users ignored them. This mirrors 25Madison’s advice that nothing validates an idea like customers willing to pay actual money.

A cautionary tale: skipping validation

We’ve also seen the downside. A hardware startup we advised poured months into building an elegant smart‑home device based on a founder’s hunch. Early adopters loved the concept in surveys, but no one pre‑ordered. When we eventually launched a pilot, less than 2 percent of site visitors converted, far below our 10 percent threshold. By then, the burn rate was high and the runway short. Investors lost confidence and the company shut down. The lesson? Validate before you build.

Reddit wisdom

On a popular forum for pre‑launch startups, a seasoned builder explained that market validation means getting people to pre‑pay for your solution, not just clicking a landing page. We agree: sign‑ups indicate curiosity, but paying customers demonstrates commitment. Treat free sign‑ups as signals, not proof.

Common pitfalls and challenges

Market validation isn’t a checkbox; it requires discipline. Here are traps to avoid:

- Chasing vanity metrics: likes, comments or press don’t mean demand. Focus on conversions and revenue.

- Biased feedback: friends and early evangelists may be supportive but unrepresentative. Seek out strangers.

- Unfocused hypotheses: testing too many variables at once makes it hard to know what worked. Be specific.

- Over‑engineering the MVP: building too much before validation wastes time and money. Start with the smallest experiment.

- Misinterpreting negative feedback: sometimes criticism relates to execution (bad UI) rather than the underlying need. Ask follow‑up questions to separate ideas from implementation.

- Ignoring timing: macro trends can make or break a market. Even a validated need can disappear if technology costs drop or regulation shifts.

- Failure to close the loop: after gathering feedback, incorporate it. Nothing erodes trust like asking users for input and ignoring it.

How validation fits into pitch decks and investor conversations

Investors are sceptical of untested ideas. They want evidence that users care. In a pitch deck, a validation slide might show:

- Market opportunity: the size of the problem and any macro trends supporting growth.

- User traction: wait‑list sign‑ups, pilot users, conversion rates. Thinslices suggests that conversion rates below 10% warrant caution.

- Evidence of willingness to pay: pre‑orders, revenue from paid pilots, letters of intent.

- Prototype or MVP learnings: key insights from usability tests or A/B experiments. A strong narrative shows how each experiment informed the next step.

Avoid overclaiming. Investors will dig into your numbers. Show real evidence, admit what you don’t yet know and explain how future experiments will answer those questions.

When to stop validating and move to build or scale

Validation doesn’t last forever. Signs you’re ready to move forward include:

- Consistent positive signals: multiple experiments across different methods show strong interest and willingness to pay.

- Retention: early users stick around and use the product regularly.

- Refined value proposition: your messaging resonates and conversions meet or exceed your thresholds.

- Clear next steps: you have a roadmap informed by user feedback, not guesses.

Beware analysis paralysis. There will always be unknowns. Set decision gates: if you hit your targets, build; if not, pivot or kill the idea. Validation continues post‑launch through feature tests and market expansion. As Lyssna notes, concept testing “remains useful even after you launch”.

Conclusion

What is market validation? It’s the disciplined practice of proving that a real market exists for your idea before you commit serious time and money. In our experience at Parallel, founders who embrace validation iterate faster, waste less and build products people actually want. Those who skip it often end up with a beautiful solution in search of a problem. Validation isn’t glamorous; it’s a process of asking uncomfortable questions and listening to what the market tells you. Start with a hypothesis, run an experiment, learn and repeat. The market—not investors or teammates—has the final say.

FAQ

1) What is the meaning of market validation?

Market validation means testing whether there’s real demand for your product idea among your target audience before investing heavily. You do this by presenting your concept to potential customers and gathering evidence—sign‑ups, interviews, pre‑orders, paid pilots—that shows they care.

2) How do you do market validation?

Write down assumptions about the problem, audience and solution; define a precise hypothesis. Identify and recruit people who fit your target profile. Choose methods such as interviews, landing pages, prototype tests, MVPs or pre‑orders. Run small experiments, collect data, analyze results and decide whether to pivot or proceed. A 10 percent conversion benchmark on landing pages is a common threshold.

3) What is market validation in a pitch deck?

It refers to the evidence you present to show that your idea has traction: sign‑ups, wait‑lists, pilot customers, pre‑orders, or usage metrics. Investors want to see concrete proof that real users are engaging with—and paying for—your solution.

4) What is the main purpose of validation?

The main purpose is to reduce risk. By testing whether a market exists and whether customers will pay, you avoid building something nobody wants. Validation also helps refine your product, messaging and pricing early, saving time and resources.

.avif)