What Is an MVP for Entrepreneurs? Complete Guide (2026)

Learn about the minimum viable product (MVP) concept for entrepreneurs, its benefits, and how to launch a lean version of your product.

Many early‑stage founders pour months into building full‑fledged products only to find that the market is ambivalent. A study from Founders Forum Group notes that 42% of startups fail because they misread market demand. That sobering statistic highlights an important truth: the biggest risk isn’t technical execution, it’s building something no one needs. This guide answers what is an MVP for entrepreneurs and shows how a lean first version can help founders test assumptions while preserving resources. We’ll cover how to apply the concept, why it matters, how to build one, and when to consider other approaches. Along the way we’ll draw on recent research and our experience working with founders at Parallel to keep the advice grounded and current.

What is an MVP for entrepreneurs?

Eric Ries, the author of The Lean Startup, defined a minimum viable product (MVP) as “that version of a new product which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least effort”. Put simply, an MVP is a lean first iteration that tests a core hypothesis. It is minimum because it contains only the essential features needed to evaluate a concept, and it is viable because it must deliver real value to early adopters. Shortcut’s product guide stresses these two attributes: skip non‑essential features and ensure the version functions well enough to satisfy users. An MVP is not just a prototype; prototypes can test technical feasibility, while an MVP is built to learn whether the problem and solution resonate with a market.

In an entrepreneurial context, the concept is about minimizing risk and cost while maximizing learning. A well‑defined MVP helps a startup validate assumptions about user needs, pricing and product‑market fit before committing significant resources. Research from 2024 dissects the term further: Lortie, Cox and their co‑authors emphasise that an MVP must include not only a working feature but also a means to distribute it and a feedback mechanism. Those elements ensure that the team can observe real user behaviour and adjust quickly.

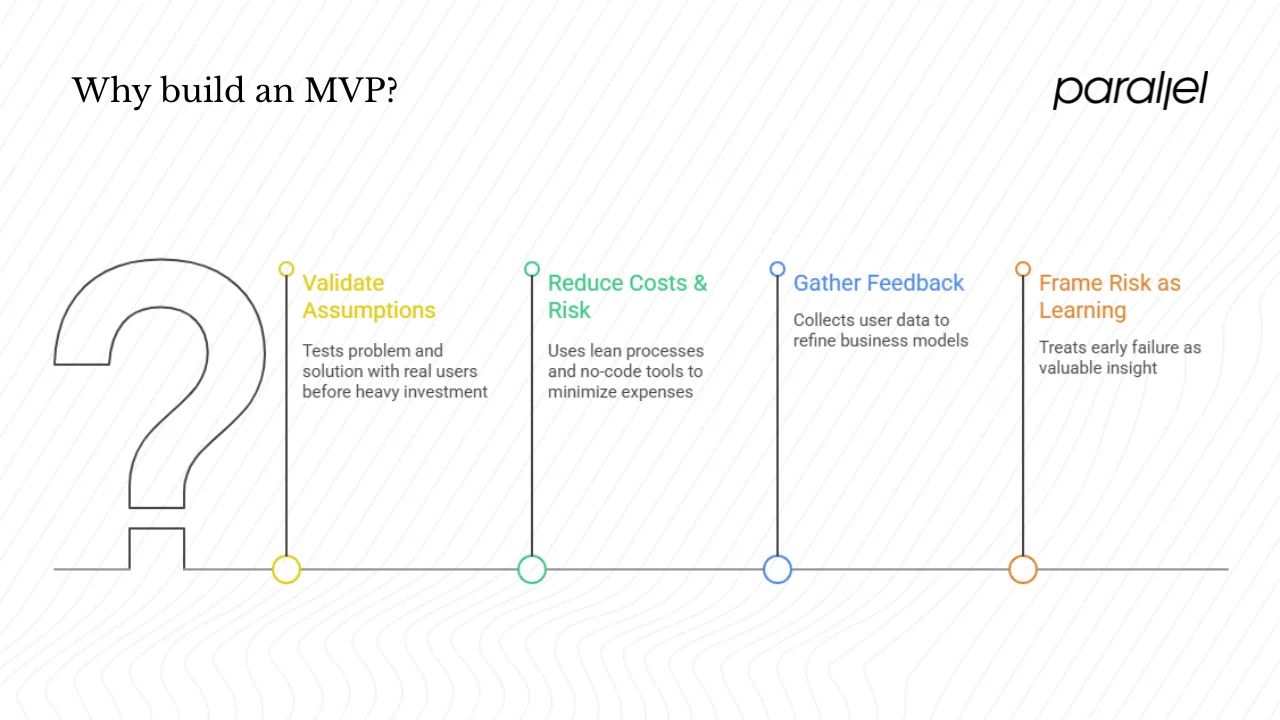

Why entrepreneurs should build an MVP

1) Testing before scaling

Early validation is the most compelling reason to build an MVP. The same Founders Forum report that highlights misreading demand as the top cause of failure also shows that only two in five startups become profitable. Launching an MVP lets you test assumptions about the problem and solution with real users before investing heavily. Productfolio reminds us that the primary purpose is “cheap or inexpensive validated learning”. Without that learning, building a large product becomes a high‑stakes gamble.

2) Reducing cost and minimising risk

Building a lean first version keeps costs down and limits exposure if the idea fails. No‑code tools and lean processes amplify this effect. A 2025 analysis of no‑code development found that organisations using such platforms save up to 70% compared with traditional development and cut development time by 90%. That speed and cost advantage allows startups to launch MVPs in days or weeks, not months. Because you commit fewer resources, you can afford to discard or pivot more easily when feedback suggests a change.

3) Gathering feedback and testing business models

Real user feedback is priceless. An MVP introduces your concept to a small but representative group of users and collects data on how they use it. Shortcut’s examples illustrate this: the Duolingo prototype used web articles as language exercises and collected translations as data. Early iterations revealed that gamification drove engagement, guiding the team to focus on user retention and eventually adopt a freemium model. Similarly, Dropbox’s founder released a simple demo video because his prototype was not ready for public release. The video explained the product’s core features and generated 70,000 beta sign‑ups, validating demand. These stories show that early feedback can confirm or challenge your business model, pricing and value proposition.

4) Framing risk as learning

Steve Blank, a mentor to entrepreneurs, distinguishes between making a version 1.0 and creating an MVP: the goal is to learn rather than deliver. In other words, an MVP is not a stripped‑down product that will eventually scale; it is an experiment. By framing risk as learning, founders can treat early failure as valuable insight and avoid sunk‑cost traps. That mindset is at the heart of what is an MVP for entrepreneurs.

MVP in the startup life cycle

An MVP sits between the initial idea and a full product launch. Lean startup methodology describes the build–measure–learn loop: build a minimal product, measure user behaviour, and learn from the results. This cycle repeats until the hypothesis is validated or a pivot is needed. For early‑stage teams, the loop needs to be fast. Linear’s 2024 reflection explains that the modern MVP is not simply a hack but a refined early version that competes in an existing category. Many markets are crowded; users expect a reasonable level of polish even in early versions. The article argues that instead of rushing to release the smallest thing, founders should narrow their target audience and spend time refining the core to compete. Their experience highlights that what is an MVP for entrepreneurs today involves a balance: it must be minimal enough to test hypotheses quickly but polished enough to stand out.

This approach contrasts with larger product teams that often have more resources and longer timelines. Entrepreneurs must prioritise speed, resource constraints and direct outcomes. The MVP stage is also the point where teams start engaging investors. Demonstrating traction through a well‑executed MVP can help attract funding and partnerships without having to build the entire product.

What qualifies as an MVP?

Not every small release is an MVP. To qualify, it should:

- Deliver a core solution. The version must solve the primary problem for your target users; it can’t be a half‑working mock‑up. Productfolio cautions against confusing an MVP with “phase 1” of a delivery plan.

- Enable hypothesis testing. The point is to validate assumptions. You should identify what you want to learn and ensure the MVP can answer that question.

- Include a feedback loop. The research paper on MVPs stresses the need for a distribution channel and an effective user feedback mechanism. Without feedback, you are flying blind.

- Be iterative. Release quickly, gather feedback, and refine. If you are not prepared to iterate, you are not building an MVP.

Common misconceptions

Several myths persist:

- “Smaller means better.” Reducing features is not the goal; providing value with minimal waste is. A tiny app that does not solve the main problem is not viable.

- “Prototype equals MVP.” Prototypes explore feasibility or design ideas. An MVP tests market demand and learning. They serve different purposes.

- “It must be a software build.” MVPs come in many forms—videos, spreadsheets, or manual services—as long as they test your core assumptions.

Examples of what qualifies and what doesn’t

- Qualifies: A landing page that explains your service and collects email sign‑ups; a manual concierge service that imitates the future automated version; a demo video like Dropbox’s that demonstrates value.

- Doesn’t qualify: A half‑finished app with missing functionality; a beautifully designed prototype with no way to test market demand; a pilot that solves a different problem than your intended product.

Knowing what an mvp for entrepreneurs means focusing on learning rather than product completeness.

Types of MVPs and examples

Different industries and goals call for different MVP formats. Here are common types and examples:

- Demo video: A short video shows the product concept, features and value. Dropbox’s 2007 video created interest and turned 5,000 beta sign‑ups into 70,000. You can adopt this format when your prototype isn’t ready for public use but you need to gauge interest.

- Landing‑page MVP: Set up a simple website explaining your product and inviting visitors to sign up. Measure conversion and gather questions to test demand and messaging.

- Wizard of Oz (Flintstone) MVP: Provide the service manually behind the scenes while presenting it as automated. Zappos sold shoes on its site without holding inventory; founders bought the shoes at local stores and shipped them. This approach tests whether customers value the service without investing in infrastructure.

- Concierge MVP: Offer the service manually and let customers know it’s manual. This works well when personal guidance is part of the proposition, such as high‑touch coaching or curation.

- Single‑feature MVP: Build one core feature that solves the main problem. You can expand later based on feedback. Slack’s initial version focused on team chat, file sharing and channels; only after users adopted those features did the company expand into search and integrations.

Selecting the right type depends on your domain, the problem you’re solving and how quickly you need feedback. There is no single answer to what is an mvp for entrepreneurs; the appropriate form is defined by the hypothesis you need to test.

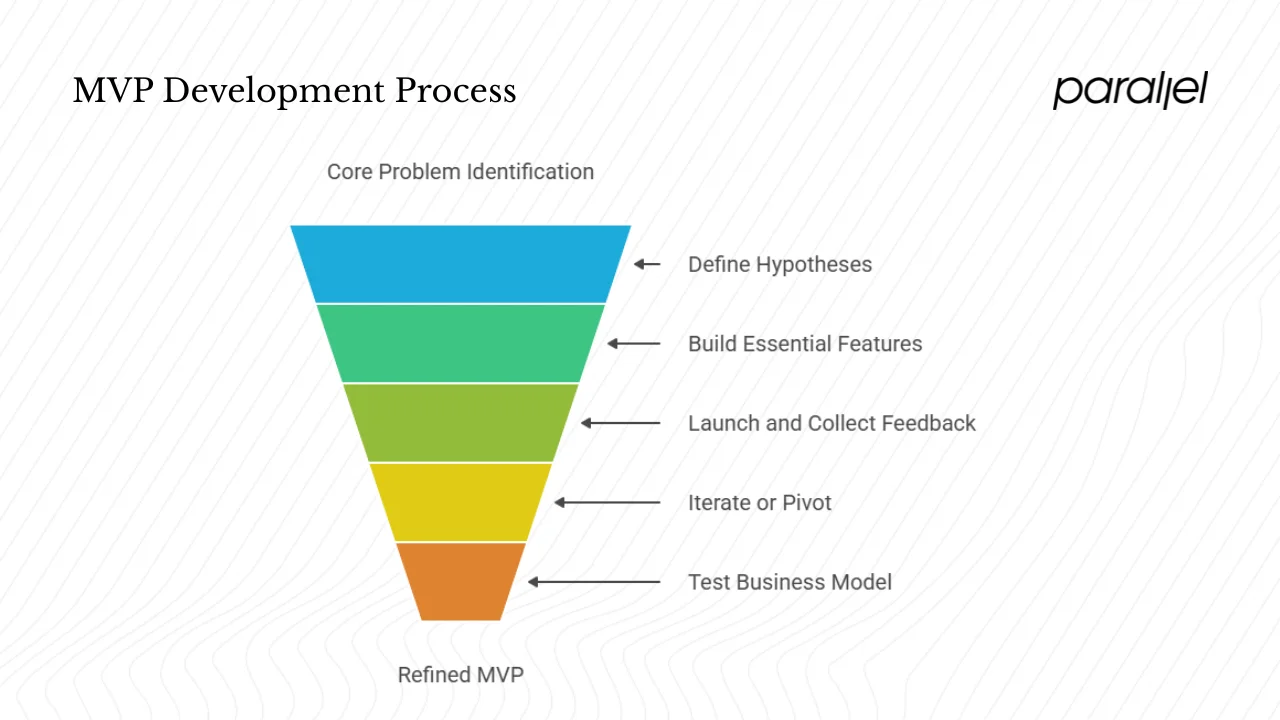

How to build an MVP: step‑by‑step

Building an effective MVP requires discipline and focus. Here’s a step‑by‑step approach grounded in both theory and practice:

- Identify the core problem and target user. Be specific. Instead of “everyone who writes,” focus on “freelance journalists who need to organise notes.” A narrow target makes it easier to design a coherent solution, as the Linear team learned when they narrowed their audience.

- Define your hypotheses. What assumptions about the problem, value proposition, and business model need to be true for your startup to succeed? List them and prioritise the riskiest.

- Decide what features are essential to test the main assumption. Resist the urge to add “nice‑to‑have” elements. Productfolio emphasises that the MVP is about learning, not delivering a version 1.0.

- Build quickly and economically. Use no‑code tools or simple prototypes to reduce cost. Data shows that no‑code platforms can reduce development time by up to 90%adalo.com, enabling you to get to market in days instead of months.

- Launch to a small group and collect qualitative and quantitative feedback. Track sign‑ups, engagement, usage patterns and pay attention to user comments. Without an effective distribution channel and feedback mechanism, you miss the chance to learn.

- Iterate or pivot. Use feedback to refine the product. If the core assumption proves false, pivot to a new hypothesis. Linear suggests that iteration is not one moment but a continuous process.

- Test the business model. Experiment with pricing, delivery methods, and acquisition channels. Early revenue models may not stick, as Duolingo discovered when it shifted from crowdsourced translations to gamified learning and a freemium model.

Throughout these steps, maintain a mindset of learning and experimentation. That mindset is central to what is an MVP for entrepreneurs.

Linking MVPs to business model testing and market entry

An MVP is more than a product—it’s a test of your entire venture. By exposing the core value proposition to real users and charging (or not), you learn if customers are willing to pay, which features matter and how you might deliver and scale. The 2024 research paper on MVPs highlights that beyond functionality, distribution and feedback channels are essential. Without them, you can’t assess whether there is a market or how customers behave.

Testing business models means experimenting with pricing and revenue mechanisms early. For example, Dropbox moved from a free beta to a freemium model once usage patterns showed strong adoption. Zappos used a manual fulfilment process to prove there was demand before investing in warehouses.

Market entry strategy is also informed by an MVP. Instead of launching an overbuilt product, you release a minimal version to a narrow segment, observe adoption and adjust. As Linear’s article notes, competing in a mature market often requires a polished early release. Balancing speed with quality is crucial; you need to deliver enough value to stand out while still learning quickly. When done well, the answer to what is an MVP for entrepreneurs becomes clear: it is your first step into the market, designed to test both the product and the business behind it.

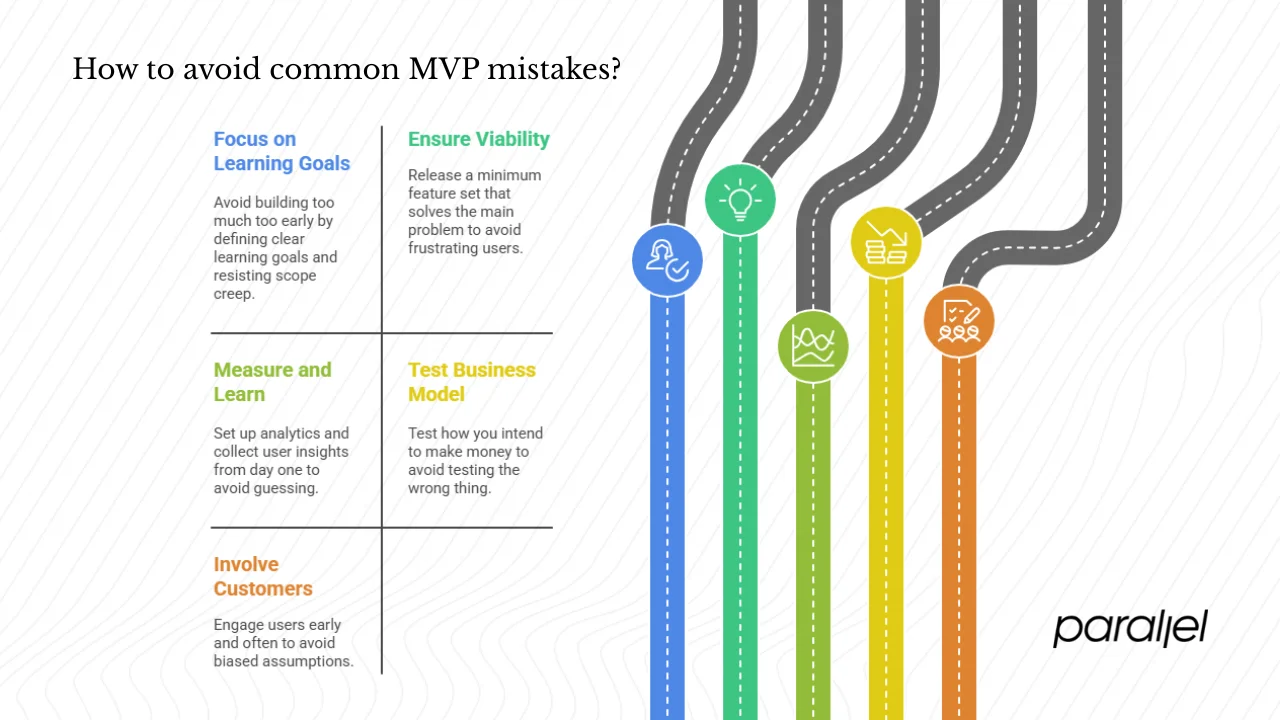

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

- Building too much too early. Founders often add features in an attempt to please everyone, which dilutes the focus and delays feedback. Avoid this by defining learning goals and resisting scope creep.

- Ignoring viability. A minimum feature set must still solve the main problem. Releasing something barely usable frustrates users and produces misleading feedback.

- Failing to measure and learn. Launching an MVP without analytics or user research means you are guessing. Set up metrics and collect qualitative insights from day one.

- Disconnecting from the business model. Your MVP should test how you intend to make money. If you give away the product without any hint of future pricing, you might be testing the wrong thing.

- Skipping customer involvement. Building in a vacuum leads to biased assumptions. Engage users early and often. Remember that the aim is to learn about customers, not to prove you are right.

By being intentional about scope, measurement and market assumptions, you can avoid these pitfalls and stay true to the spirit of what is an MVP for entrepreneurs.

Measuring success of your MVP

Success metrics fall into two categories: engagement indicators and learning indicators.

- Engagement: Track how many users sign up, use the product regularly, complete key actions and refer others. Retention and activation rates reveal whether the core value resonates.

- Conversion: If you are testing pricing, measure the percentage of users who convert to paying customers, average revenue per user and churn. Early revenue signals a viable business model.

- Qualitative feedback: Analyse comments, complaints and suggestions. Themes in qualitative data often reveal unmet needs or misaligned assumptions.

- Learning outcomes: Perhaps the most important measure is whether the MVP answered your hypothesis. Did it confirm or refute your assumptions about the problem, value proposition or business model? Each iteration should reduce uncertainty.

- Cost vs. value: Compare the resources invested to the learning gained. An MVP that costs too much relative to the insight obtained defeats the purpose. Leveraging no‑code tools helps maintain this balance.

These metrics help you decide whether to continue, pivot or stop. The choice should be guided by evidence rather than sunk costs.

Scaling after the MVP

Once your MVP has achieved its learning goals and demonstrates traction, it’s time to plan the next steps.

- Add features carefully. Use feedback to prioritise improvements. Don’t rush to add every requested feature; focus on what moves the needle for your target users.

- Improve quality and infrastructure. Address technical debt, improve performance and ensure reliability. Scaling with a shaky foundation creates future bottlenecks.

- Expand your market. Once you’ve achieved a product–market fit with a narrow audience, consider adjacent segments. Use data to identify where demand is strongest.

- Refine your business model. Introduce pricing tiers, subscriptions or usage‑based billing based on what you’ve learned. Continue to test pricing strategies on new cohorts.

- Keep testing. Even as you grow, maintain the build–measure–learn mindset. Market conditions change, and assumptions can become outdated.

Scaling is not the end of the process. You’re moving from a learning phase to a growth phase while still applying the same discipline that defines what is an MVP for entrepreneurs.

When not to use an MVP and alternatives

While MVPs are powerful tools, they are not always appropriate. Situations where a fuller product might be warranted include:

- High regulatory or safety requirements. In healthcare, aviation or finance, a minimal product may not meet safety or compliance standards. A proof of concept or pilot with full compliance built in may be necessary.

- Hardware with long lead times. Physical products often require investment in tooling and supply chains that cannot be easily iterated. In such cases, a prototype or pilot program can test user acceptance before mass production.

- Markets with network effects or winners‑take‑all dynamics. Sometimes speed and scale are critical to capture the market. In those cases, an MVP might not provide enough momentum.

Alternatives include:

- Proof of concept (PoC): A technical experiment to verify feasibility without exposing it to users.

- Pilot: A limited‑scope deployment of a full product in a controlled environment, often used in regulated industries.

- Minimum sellable product (MSP): A version that is complete enough to sell and support on the market, often used when the minimal version must meet certain standards.

Deciding whether to use an MVP or another approach depends on your domain, risk tolerance and the nature of your hypotheses.

Conclusion

By now it should be clear what is an mvp for entrepreneurs: a lean, functional version of a product designed to maximise learning while minimising waste. Research shows that misjudging market demand is the top reason startups fail, and a well‑executed MVP counters that risk by exposing hypotheses to real users early. An MVP must deliver core value, include a feedback loop and support iteration. It should test business model assumptions, gather qualitative and quantitative feedback and inform your market entry strategy. When the MVP validates your idea, you can scale with confidence; if it doesn’t, you pivot with minimal sunk cost.

As you plan your next product, ask yourself: what is the smallest thing you can build to test your riskiest assumption? How will you collect feedback and measure success? Treat the MVP not as a quick release but as an ongoing process of learning and improvement. In our work at Parallel we’ve seen teams waste months on features that customers never use. We’ve also seen the power of lean experiments to unlock genuine traction. Embrace that spirit of curiosity and disciplined testing, and you’ll greatly improve your odds of building something people truly need.

FAQ

1) What is an MVP in entrepreneurship?

The term MVP stands for minimum viable product. Eric Ries defines it as the version of a new product that enables a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least effort. For entrepreneurs, an MVP is a strategic tool: a lean first version that solves a core problem, includes a feedback loop and validates assumptions about the market and business model. It is not about shipping a full product; it is about learning quickly and efficiently.

2) What qualifies as an MVP?

An MVP must deliver real value to early adopters while remaining minimal. It should have just enough features to solve the core problem, include a mechanism to collect feedback and be designed to test a specific hypothesis. Prototypes or incomplete applications that don’t allow for user learning do not qualify. Examples that qualify include a demo video that explains the product (like Dropbox), a landing page that collects email sign‑ups or a manual service that mimics an automated solution.

3) What is an example of an MVP in business?

Dropbox’s early demo video is a classic example. Founder Drew Houston recorded a simple video explaining how his file‑syncing service would work and offered beta sign‑ups. The video went viral, and sign‑ups jumped from 5,000 to 70,000, demonstrating strong demand before the full product existed. Zappos used a Wizard of Oz MVP: they photographed shoes, listed them on a site and, when orders came in, bought the shoes from local stores and shipped them. These examples show how lean experiments can validate both demand and business models.

4) What does it mean to be an MVP?

In sports, MVP often refers to the “most valuable player.” In entrepreneurship and product development, it stands for minimum viable product. Being an MVP means being the smallest functional version of a product that lets you test assumptions and gather learning. For entrepreneurs, it also means adopting a mindset of continuous experimentation and improvement. Instead of chasing perfection, you seek rapid feedback and adapt accordingly.

.avif)