What Is Pagination? Implementation Guide & SEO Examples

Master pagination for websites and apps. Learn how to implement clear navigation, improve SEO crawlability, and enhance user experience in 2026. Read the expert guide!

In product conversations with founders and product managers, one phrase surfaces again: what is pagination? The answer seems simple, yet the implications for a growing web product are complex.

As your dataset scales from tens to thousands of records, pages that once loaded instantly now crawl. Users can’t find older entries, and Googlebot stops indexing deeper content. Pagination splits content into discrete pages with clear navigation controls.

This article draws on my experience leading design and product strategy at Parallel to explain why pagination matters for early‑stage startups, how to implement it thoughtfully, and how to avoid pitfalls that can hurt user experience or search visibility.

What is pagination and why does it matter?

In web contexts, we use pagination to divide sets of content — lists of blog posts, product catalogues, search results or database records — into sequential pages. Each page contains a subset of the items, linked by numbered navigation or previous/next controls. This definition may sound technical, but it captures the essence: break a large dataset into manageable chunks that people and machines can digest. When product leaders ask what pagination is, they sometimes confuse it with infinite scroll; understanding this definition helps clarify the distinction.

Navigation, segmentation and numbering

Three ideas underpin pagination: navigation, content segmentation and page numbering. Navigation means giving users controls to move through pages — for instance a row of numbers with “previous” and “next” arrows. Content segmentation refers to splitting a large list into logical chunks rather than presenting everything at once. Page numbering provides a mental model (“page 1 of 5”) and allows direct jumps to a specific part. Together, these elements make long lists less overwhelming and help users understand where they are within a dataset.

Why startups should care

Pagination is not just a UI detail; it influences performance, content management, user retention and SEO. Without pagination, rendering hundreds of items can slow down pages and frustrate users on slower networks. Pagination ensures that only a limited number of records are loaded at a time, improving load times and server performance. It also structures your content, making it easier for users to move through the list and for teams to maintain archives. Search engines rely on these structures to crawl deeper pages; properly paginated pages provide crawlable links, improving indexing. For early‑stage startups, planning pagination early supports scaling, reduces technical debt and avoids the scramble when content volume grows.

Common use cases of pagination

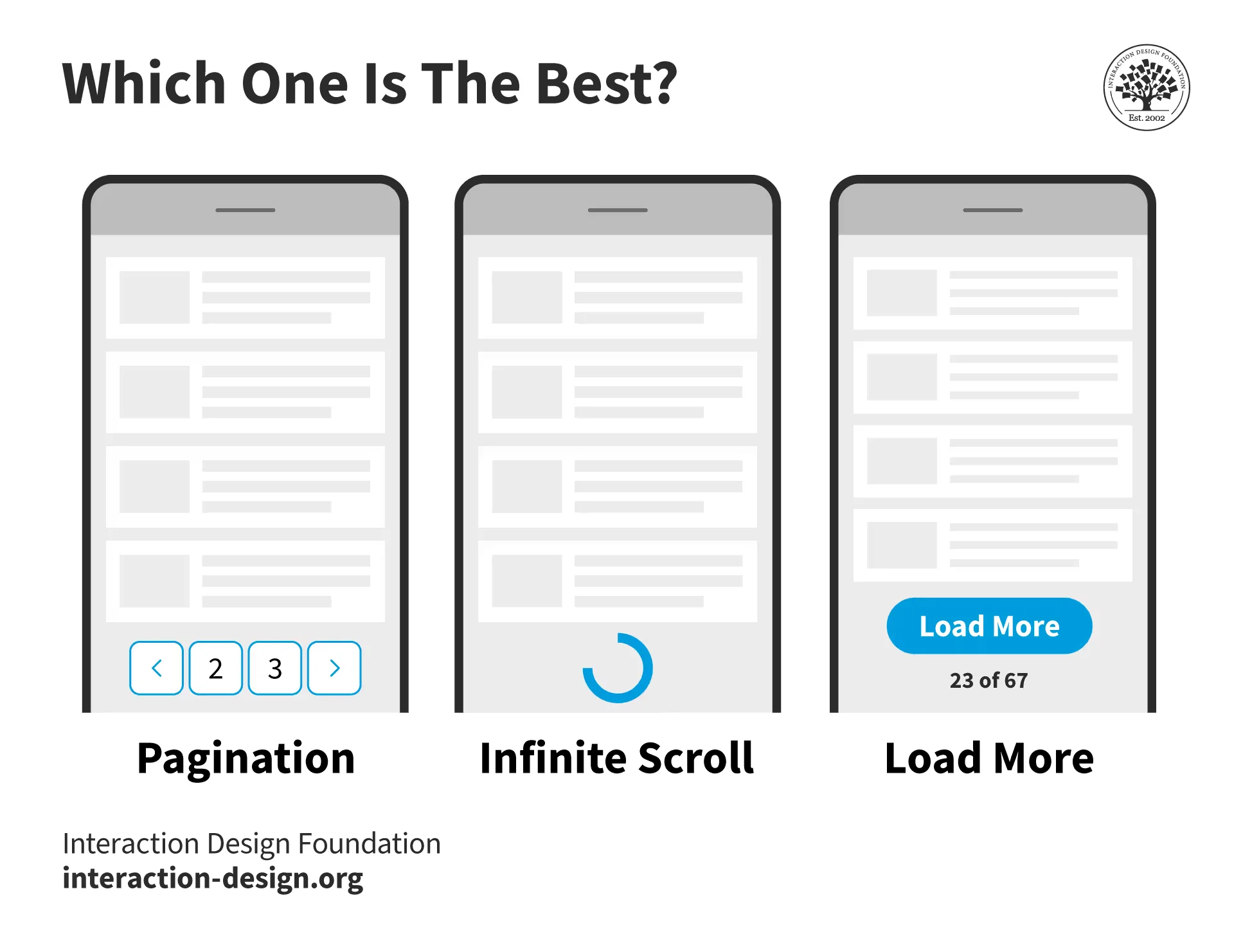

Pagination crops up across a range of product experiences. Recognising these use‑cases helps teams decide when to adopt it and when alternatives such as “load more” or infinite scroll may be better.

- Content lists and blog archives: News sites, blogs and knowledge bases use pagination to organise articles. A category page might show ten posts per page to keep the layout uncluttered. This approach prevents users from wading through hundreds of headlines at once and makes it easier for search engines to reach older posts.

- Product catalogues and e‑commerce: Large catalogues often have thousands of products. Splitting them into pages with query parameters like ?page=2 helps users browse logically. The Search Engine Land analysis notes that even major retailers use this pattern to prevent excessive scrolling and to aid discovery.

- Search results, filters and data tables: In dashboards or admin panels, data tables often show a limited number of rows with pagination controls. This improves performance and allows users to focus on the current slice of data rather than being overwhelmed by the entire dataset.

- APIs and backend retrieval: Pagination isn’t just about the user interface. APIs that return large lists — for example, retrieving thousands of customer records — often implement pagination to control load. The OneTrust developer guide distinguishes between page‑based (offset) pagination using parameters like page and size, and cursor‑based pagination where a continuation token acts as a pointer.

- When not to paginate: Short lists don’t need pagination. For example, a list of five items can simply be displayed in full. Infinite scroll or “load more” can be suitable for feeds where users want to keep exploring, such as social media streams. But infinite scroll has SEO drawbacks because crawlers rarely scroll down to trigger new content; we discuss this later.

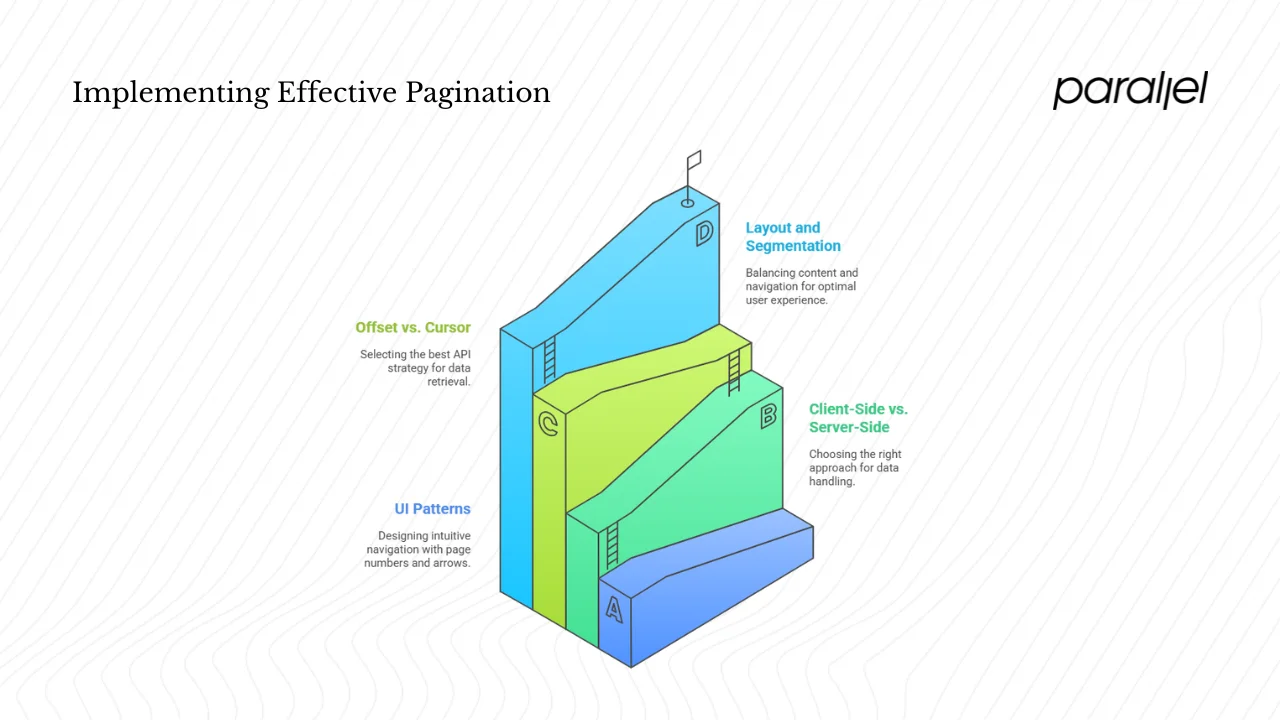

How pagination works: design, implementation and patterns

1) UI and experience patterns

Pagination is a user interface pattern for presenting large result sets. The familiar row of page numbers at the bottom of a list allows users to jump directly to page 3 or skip ahead ten pages. Arrows provide sequential navigation. Some designs show only a few numbers around the current page with ellipses indicating skipped pages; this avoids clutter when there are dozens of pages. You might include “first” and “last” buttons for long lists. Marking the current page number helps users see where they are. Compared with infinite scroll, pagination gives users a sense of completion and control, making it easier to return to a particular position in the list.

2) Client‑side versus server‑side

There are two broad ways to implement pagination: client‑side and server‑side. In client‑side pagination, all data is loaded into the browser and then sliced into pages using JavaScript. Wikipedia notes that client‑side pagination is suitable only when there are very few records; all records are returned and the client uses JavaScript or CSS to display separate pages. Server‑side pagination is more common; each page request fetches only the subset of data needed. This approach supports large datasets, improves initial load times and caters to users without JavaScript. Hybrid approaches using AJAX fetch additional pages on demand.

3) Offset versus cursor pagination in APIs

At the API layer, there are two popular strategies. Offset (page‑based) pagination uses query parameters such as page=0 and size=20 to return a specific slice of results. The OneTrust guide describes how the API response includes metadata like totalPages, size and pageNumber. Developers loop through pages until all results are retrieved. Offset pagination is simple to implement but can be inefficient when dealing with very large datasets because skipping many rows becomes slow.

Cursor (keyset) pagination uses a token returned by the server to mark where the previous request left off. The next request includes this token to fetch the subsequent batch. This method is better for real‑time or frequently changing data sets because it avoids missing items when new records are inserted between requests. However, you can only move sequentially — you can’t jump straight to page 10 because there is no concept of page numbers.

4) Interaction with layout and content segmentation

Designers must decide how many items to show per page. Too few items and users click constantly; too many and the page becomes long. The Interaction Design Foundation suggests dividing the overall dataset into smaller groups and finding a balance between content, readability and ease of navigation. The layout should maintain context across pages, for example by repeating table headers or filters so that users don’t lose orientation. In content segmentation, ensure each page contains meaningful content, not arbitrary splits; for example, avoid splitting a paragraph mid‑sentence.

Benefits and risks of pagination

Benefits

- Improved user experience: Splitting long lists into pages reduces cognitive load. Users can digest content in smaller portions and feel a sense of progress. The Uxcel glossary emphasises that pagination empowers users to decide how they browse: they can skip to later pages, return to earlier ones or jump directly to a desired section.

- Performance gains: Loading only a subset of data reduces server strain and speeds up response times. This is crucial for mobile users and slower networks.

- Better content management: For product teams, pagination imposes a structure that makes content easier to organise and manage. Archives and search pages remain tidy, and adding new items doesn’t disrupt existing layout.

- SEO and indexing: Search engines recognise pagination structures and use them to find deeper content. Without pagination, crawlers may struggle to discover nested pages. A properly paginated site provides internal links that ensure no page becomes orphaned.

Risks and pitfalls

- SEO missteps: Poor implementation can create duplicate content or hamper crawling. Using the same canonical tag for all paginated pages or failing to provide unique URLs can confuse search engines. The Google Search Central guidance notes that each page should have a unique, crawlable URL and that crawlers don’t execute JavaScript actions to load more content.

- User experience traps: Too many page numbers or confusing controls can frustrate users. If navigation is hidden behind a dropdown or placed away from the list, people may not realise there is more content. On mobile devices, pagination controls need to be large enough to tap.

- Performance issues: Allowing users to “view all” items can defeat the purpose of pagination if the dataset is huge. Similarly, if each page triggers heavy database queries or unoptimised API calls, the benefit of pagination is lost.

Strategic considerations for startups

Deciding between pagination, “load more” and infinite scroll depends on your product’s goals. Pagination works well when users need to know their place in a list or when they might skip ahead. Load more is suited to feeds where users want to continuously discover new content without losing context. Infinite scroll creates a continuous flow but can hurt SEO because crawlers don’t trigger JavaScript to load additional items. For early‑stage products, start with simple pagination; as you gather analytics on page‑to‑page drop‑off, adjust your pattern. Factor in mobile behaviour: a “load more” button may be more practical on small screens.

CTA: Book a call

SEO impact and best practices

If you’re still wondering what pagination is and its effect on SEO, this section explains how search engines treat paginated content.

How search engines view paginated content

Search engines need to crawl all relevant pages of a site. Pagination structures help them discover deeper content and maintain internal linking. The Search Engine Land article notes that pagination improves indexing, crawl efficiency and internal linking: crawlers can prioritise valuable pages while ignoring less important ones. Without pagination, deeply nested content may remain undiscovered.

Google’s documentation emphasises that pagination uses numbered links, whereas “load more” and infinite scroll rely on JavaScript events. Google primarily indexes URLs found in anchor tags and does not trigger JavaScript functions for content updates. Each paginated page should have its own URL with sequential links, and the first page should not be the canonical URL for the rest. Avoid indexing filtered or sorted versions of the same list to prevent duplicate content.

Important SEO practices

- Ensure each page has a unique, crawlable URL; avoid using fragment identifiers like #page2 because search engines may ignore them.

- Use proper <a href> links for navigation so crawlers can follow them. Avoid JavaScript-only pagination.

- Implement self‑referencing canonical tags; avoid pointing all pages to page 1 unless you have a “view all” page. The Search Engine Land piece notes that Google deprecated rel=prev/next but still recognises pagination structures.

- Include meaningful content on each paginated page. Avoid thin pages that only show items without context — add headings, descriptions or summaries to help search engines understand the page’s purpose.

- Optimise crawl budget by limiting the number of paginated pages that search engines need to traverse. Use internal linking (e.g., blog archives) to ensure pages deeper than page 3 are still reachable.

Startup checklist for pagination and SEO

- Audit your content: Identify lists with more than about twenty items; plan to paginate them.

- Design a clean URL structure: Use query parameters or clean paths (/page/2/) for pages. Avoid mixing filters and sorts within the same URLs.

- Build crawlable navigation: Use standard anchor tags for numbers and previous/next controls. Avoid using <button> elements that require JavaScript to fetch content.

- Monitor analytics: Track drop‑off between pages using analytics tools. High drop‑off on page 2 could indicate that items per page are too low or that navigation is unclear.

- Check search console: Verify that deeper pages are indexed. If they are not, revisit your internal linking or sitemap.

- Optimise for mobile: Consider showing fewer items per page on small screens, or use a “load more” pattern combined with unique URLs to maintain crawlability.

Pagination versus alternate patterns

Pagination offers structure and orientation; “load more” and infinite scroll deliver continuous content but can hinder indexing. Search Engine Land notes that infinite scroll relies on JavaScript and may orphan content because search bots don’t scroll down. For conversion‑oriented flows — such as checkout or onboarding — pagination provides clear milestones and reduces risk of lost context. “Load more” suits casual browsing where users may keep scrolling as long as interesting items appear. For early‑stage startups with limited resources, traditional pagination is easier to implement and more SEO‑friendly.

Practical implementation: from design to code

Design considerations

Designers and product leaders should start by deciding how many items to show per page. Consider user behaviour, content type and device. For blog posts, 10–20 items per page works well; for tables, you might choose 25 or 50. Provide navigation controls: previous/next buttons, page numbers and optionally first/last buttons. For long lists, use ellipses to avoid clutter. Always show the current page and total pages to orient users. On mobile, simplify controls — a “load more” button may be more accessible than tiny page numbers.

Accessibility matters. Use proper labels (“Page 2 of 5”), focus states and keyboard navigation. The Uxcel glossary emphasises that pagination provides predictable navigation points that screen readers can interpret.

Engineering considerations

Choose a backend pagination strategy. Offset pagination is easy to implement using SQL LIMIT and OFFSET or API parameters page and size. However, it can become inefficient for large data sets because skipping rows is expensive. Cursor pagination uses a unique identifier or timestamp as a pointer to the next batch. It provides consistent results even when new records are added between requests but requires more complex logic. Decide based on your dataset size and how often it changes.

On the client side, ensure that API calls include pagination parameters and handle responses accordingly. In single‑page applications, update the URL when users change pages using pushState so that they can bookmark a specific page. Pre-fetching the next page can improve perceived performance but should be balanced with bandwidth usage.

SEO and analytics integration

Generate unique URLs for each page and update your sitemap if you want search engines to discover them. Use analytics events to measure user flow across pages. If most users drop off after page 1, experiment with more items per page or a “load more” button. Implement A/B tests to compare pagination patterns. For SEO, avoid blocking paginated pages via robots.txt or canonical tags; instead, let search engines crawl and index them.

Code snippets

Here’s a simplified HTML snippet for pagination navigation:

<nav class="pagination" aria-label="Page navigation">

<a href="?page=1" class="prev" aria-label="Previous">«</a>

<a href="?page=1" class="page" aria-current="page">1</a>

<a href="?page=2" class="page">2</a>

<span class="ellipsis">…</span>

<a href="?page=5" class="page">5</a>

<a href="?page=2" class="next" aria-label="Next">»</a>

</nav>

And a pseudo‑code example of offset pagination in an API:

def get_paginated_results(page: int = 0, size: int = 20):

offset = page * size

query = "SELECT * FROM items ORDER BY created_at DESC LIMIT %s OFFSET %s"

results = db.execute(query, (size, offset))

return results

# Client calls

page = 0

while True:

data = get_paginated_results(page=page, size=20)

if not data:

break

process(data)

page += 1

Cursor pagination using a continuation token might look like this:

def get_cursor_results(cursor: str = None, size: int = 20):

if cursor:

return api.post("/items", json={"size": size, "requestContinuation": cursor})

else:

return api.post("/items", json={"size": size})

cursor = None

while True:

response = get_cursor_results(cursor)

data = response["content"]

process(data)

cursor = response["pageable"]["requestContinuation"]

if not cursor:

break

These examples show how pagination is handled at the code layer. In practice, you would also include error handling, rate limit considerations and caching.

When to revisit pagination

Pagination isn’t a one‑time decision. As content grows, revisit how many items you show per page and whether your navigation pattern still works. Monitor performance metrics and drop‑off rates and adjust when user behaviour changes. When mobile usage increases, consider reducing items per page. Keep up with search engine guidance — Google deprecated rel=prev/next in 2019, indicating that SEO practices change over time.

A startup case study: ShopStart’s catalogue problem

To make this discussion concrete, let’s look at a hypothetical early‑stage e‑commerce startup, “ShopStart,” that sells artisanal goods. In its first version, the product catalogue page listed all 100 items on one page. At launch this wasn’t an issue; load times were acceptable and customers could scroll easily. Over six months the catalogue expanded to over 1,000 items. Page loads slowed to a crawl, and customers complained about not finding older products.

During a discovery session, we asked the team what pagination is? They admitted that they hadn’t considered it past a simple table. We proposed splitting the catalogue into pages of 20 items and adding navigation at the bottom. The design team created a clean row of page numbers with previous/next arrows. Developers implemented offset pagination with page and size parameters. We also ensured each paginated URL was crawlable and added internal links from category pages. Once launched, page load times dropped by 70%, bounce rates decreased and older products began receiving traffic from search engines.

Not everything was perfect. We saw a sharp drop‑off after page 3. Analytics revealed that customers rarely progressed past page 2. To surface more products earlier, we added sorting options (e.g., popularity, price) and increased the default items per page from 20 to 40. We also tested a “load more” button on mobile. These iterations show that pagination is part of an ongoing design and product conversation, not a one‑time feature.

Reflection and take‑aways

Pagination answers a simple question — what is pagination — but its impact touches UI design, engineering and SEO. It is the process of splitting content into discrete pages, providing navigation controls and numbering to help users orient themselves. For startups, pagination improves performance, user experience, content management and search visibility. Implement it early, choose the right pattern (offset vs cursor) for your data, and design intuitive controls. When used thoughtfully, pagination becomes part of your product architecture rather than an afterthought.

Action points:

- Audit pages with long lists and decide whether to add pagination, “load more” or infinite scroll.

- Define a sensible number of items per page based on user behaviour and device type.

- Design clear navigation with visible page numbers and previous/next controls; mark the current page.

- Choose a backend strategy (offset or cursor) and implement API parameters accordingly.

- Ensure each page has a unique, crawlable URL; avoid JavaScript‑only pagination.

- Monitor analytics and search console; iterate on items per page and navigation patterns.

- Keep accessibility in mind — use aria labels and focus states for screen readers.

At Parallel, we’ve seen teams overlook pagination until they feel the pain. By planning early and bringing design, engineering and SEO perspectives together, you set up your product to scale gracefully. The question of pagination may be simple, but the answer – and the decisions it inspires – will influence user satisfaction and search visibility for years to come.

Frequently asked questions

1) What is pagination with an example?

In web development, pagination is splitting content into numbered pages. For example, an e‑commerce category might show products 1–20 on page 1, products 21–40 on page 2 and so on. Users click page 2 to see the next twenty products. This structure helps them move through large catalogues and improves performance.

2) How do you paginate a page?

Start by deciding how many items to show per page. Design a navigation control with page numbers, previous/next links and optionally first/last buttons. On the backend, fetch only the relevant slice of data using offset (page and size) or cursor parameters. On the front end, update the URL to reflect the page number and render the returned data. Ensure navigation links are anchor tags so crawlers can follow them.

3) What is pagination in coding?

In code, pagination means dividing a dataset into smaller groups. Two common patterns are offset pagination (skip page * size records and return the next size records) and cursor pagination (use a token to fetch the next batch). Developers use SQL LIMIT/OFFSET or API parameters to implement this. Pagination ensures that applications don’t load an entire dataset at once, reducing memory and network overhead.

4) What is pagination in the REST API?

A REST API that returns large lists typically supports pagination parameters. Page‑based APIs accept page and size parameters and return metadata like totalPages. Cursor‑based APIs return a requestContinuation token; clients include this token in subsequent requests to retrieve the next batch. The response often includes metadata (such as size, first, last, numberOfElements) to inform clients how to handle further requests. Pagination helps control server load and network traffic while giving clients control over the amount of data retrieved.

.avif)