What Is Participatory Design? Guide (2026)

Discover participatory design, where designers and stakeholders co‑create solutions through collaboration.

In the rush to ship features, I’ve seen early‑stage teams build in isolation and later wonder why those features gather dust. This guide answers what is participatory design and explains how involving your users early can be a safety net for lean teams. Participatory design is more than a user‑testing activity; it invites people who will live with your product into the process itself. In the next sections I’ll unpack definitions, origins, core principles, comparisons with other methods, when and how to apply participatory design, a process template, case examples and a set of tools to help you get started.

What is participatory design? (Origins, philosophy and theory)

Participatory Design is a way of creating products with users, not just for them. It involves bringing the people who will actually use the product into the design process, so their ideas, needs, and feedback shape the outcome from the start.

Participatory design grew out of workplace democracy movements in Scandinavia during the 1970s and 1980s. Researchers, government agencies and labour unions collaborated on technology projects to ensure new systems served workers rather than just management. A widely cited project with Norway’s iron and metal workers involved union representatives working alongside government researchers to propose better shop‑floor planning systems. This history matters because it seeded essential values: sharing decision‑making power, recognising the expertise of non‑designers and challenging the professional bias known as déformation professionnelle—a cognitive tendency to see problems only through one’s own professional lens.

Participatory design evolved outside factory settings. Urban planners used it for neighbourhood renewal, community organisers for public services and software designers for early computing projects. From the 1990s onward it merged with human‑computer interaction, design thinking and human‑centred design. It remains a philosophy as much as a method: it argues that design decisions should be made with, not simply for, those affected.

The methodology balances openness with structure. Researchers emphasise that participatory design is not a single technique but a set of approaches spanning recruitment, facilitation, prototyping and evaluation. A 2024 systematic review of 88 studies showed that most participatory projects focused on intangible systems and recruited stakeholders across multiple phases of design. The review identified 14 specific techniques and stressed that involving stakeholders early and across stages yields richer insights. The tension lies in giving participants agency while still guiding the process toward a viable product.

Core principles and pillars

1) Broaden involvement

At its core, participatory design invites end users and stakeholders to work with designers, not merely react to prototypes. The Interaction Design Foundation notes that participatory design involves end users in the creation process so that products and services better meet their needs. In practice this means recruiting people affected by the product (customers, support staff, regulators and partners) and ensuring that marginalised voices are represented. The trade‑off: achieving a representative group takes time and effort and may slow early sprints.

2) Collaboration and shared creation

Creating together means that participants are co‑authors of ideas, not just respondents. The same IxDF guide emphasises collaboration and empowerment as core principles. Co‑creation workshops, sketching sessions and storyboarding enable participants to translate tacit knowledge into tangible concepts. Facilitation skills matter here. Sessions can drift if they become therapy sessions or if a few voices dominate. Skilled facilitators balance structure with openness and help synthesise contributions into actionable concepts.

3) Varied voices and public input

Participation should include people from different backgrounds, roles and abilities. The Wacnik review found that stakeholder recruitment methods varied widely across projects and that the most effective efforts spanned multiple stages. Inviting those who are usually ignored—such as older adults, rural workers or people with disabilities—adds complexity but surface needs that surveys miss. In our work with an assistive‑technology startup, involving visually impaired users from the outset revealed context‑of‑use challenges (battery life, outdoor glare) that the team had overlooked. Without those perspectives, we would have optimised for aesthetics over usability.

4) Iterative cycles

Participatory design is iterative. You plan, recruit, co‑ideate, prototype, test and refine—then repeat. Arcia et al. (2024) point out that participatory design is an “increasingly common” method in health informatics and emphasise that well‑designed visualisations improve comprehension and engagement. Iteration is costly in time and effort, but it uncovers latent issues early. It also helps participants see their input reflected in successive versions, which builds trust and cultivates a sense of ownership.

5) User‑centred without hierarchy

Many teams use user‑centred design where researchers mediate between users and designers. Participatory design pushes further: it seeks to diminish the gap between the “design expert” and the “user expert”. According to IxDF, participatory design emphasises inclusion, collaboration, empowerment, iteration and contextual understanding. The challenge is balancing user desires with constraints such as business goals and technical feasibility. We often bring the product owner and engineering lead into sessions so trade‑offs can be discussed openly.

Participatory design vs related methods

1) Co‑design

The term co‑design is often used interchangeably with participatory design, but there are differences. Co‑design usually refers to joint ideation activities (workshops, sketching) whereas participatory design spans a wider arc—covering discovery, ideation, prototyping and even governance. A 2024 case study on co‑design for telepractice services emphasised that co‑designers balanced idealism with realism and valued small group settings. Co‑design is powerful for generating ideas but may not address recruitment, decision‑making or long‑term governance. I use “co‑design” to describe shorter sessions within a broader participatory process.

2) User‑centered or human‑centered design

User‑centered design emerged from ergonomics and emphasises designing for users by studying their needs, then testing solutions. Participatory design goes further by designing with users. IxDF explains that in user‑centered design, designers often act as mediators, bringing users into testing or feedback sessions. Participatory design invites users into brainstorming, decision‑making and iteration. This shift redistributes power: users can veto features or propose alternatives. However, participatory design requires more time and may not suit quick A/B tests or low‑stakes features.

3) Participatory development and participatory action research

Participatory development comes from community development and NGO work. It involves local communities in planning and implementing projects. The Simprints case study notes that participatory design empowers users and supports local ownership but that existing knowledge is fragmented when applied in low‑resource settings. Participatory action research combines research and action by involving participants as co‑researchers; it often aims for social change rather than product adoption. These approaches share philosophies of agency and empowerment but differ in context and scale. For a small SaaS team shipping a new workflow, participatory development’s community focus may be overkill.

4) When participatory design is not right

If your timeline is extremely tight, if users are inaccessible or uninterested, or if the stakes are low, participatory design might not be the best option. Guerrilla testing, A/B experiments or analytics may be quicker. For example, our team once built a small internal tool for automating invoice exports. The users were our own finance colleagues, they were happy with a basic interface and had no interest in co‑designing it. In that case a brief interview and quick prototype sufficed.

When and why to use participatory design

Benefits

- Better problem–solution fit – When people who will use your product help craft it, you reduce the risk of building unused features. The systematic review showed that in 65 of 88 studies, stakeholders participated across multiple stages, suggesting that continuous involvement leads to richer insights.

- Uncover latent needs – Participatory design surfaces needs that surveys or interviews miss. In our work with an HR SaaS startup, employees created storyboards for performance reviews. They revealed anxieties about fairness that wouldn’t surface in a questionnaire.

- Build trust and ownership – People are more likely to champion a product they helped craft. An IxDF article emphasises that empowerment is central; participants feel valued when their ideas shape the outcome.

- Detecting issues early – Co‑creating low‑fidelity prototypes helps spot context‑specific problems before you commit. A 2024 tutorial on participatory design of health visualisations notes that well‑designed visualisations improve comprehension and behaviour, showing the value of early feedback.

- Encourage innovation – Bringing together engineers, designers and users sparks unexpected ideas. Cross‑disciplinary groups challenge assumptions and reduce professional blind spots.

- Save rework costs – Iterative cycles may seem slow, but they prevent expensive pivots later. Fixes at the prototype stage are cheaper than code rewrites post‑launch.

Risks and challenges

- Coordination overhead – Recruiting participants, scheduling workshops and synthesising feedback demand time and planning. Startups must allocate resources accordingly.

- Recruitment bias – If you only involve vocal or available participants, you risk designing for a niche. The Wacnik review notes the diversity of recruitment methods; aim for variety in demographics, roles and perspectives.

- Managing conflicts – Stakeholders may have conflicting priorities. Facilitators need to mediate and sometimes make tough calls. Transparent decision logs help here.

- Facilitation skill – Good participatory design requires skilled facilitators to create safe spaces, ensure balanced participation and translate insights into actionable decisions.

- Scope creep – Without clear boundaries, sessions can devolve into “let’s redesign everything.” Set the scope and articulate what will change and what will remain fixed in this iteration.

- Risk of majority rule – Loud majority voices may drown out niche but important needs. Use techniques like small-group work and anonymous voting to mitigate this risk.

Trade‑offs

Participatory design involves decisions about depth versus breadth (how deeply to involve a few participants versus how broadly to reach many), formality versus informality and control versus openness. You can vary the degree of agency—from consultative (users give input) to collaborative (users have decision rights). The right mix depends on your product, timeline and team maturity.

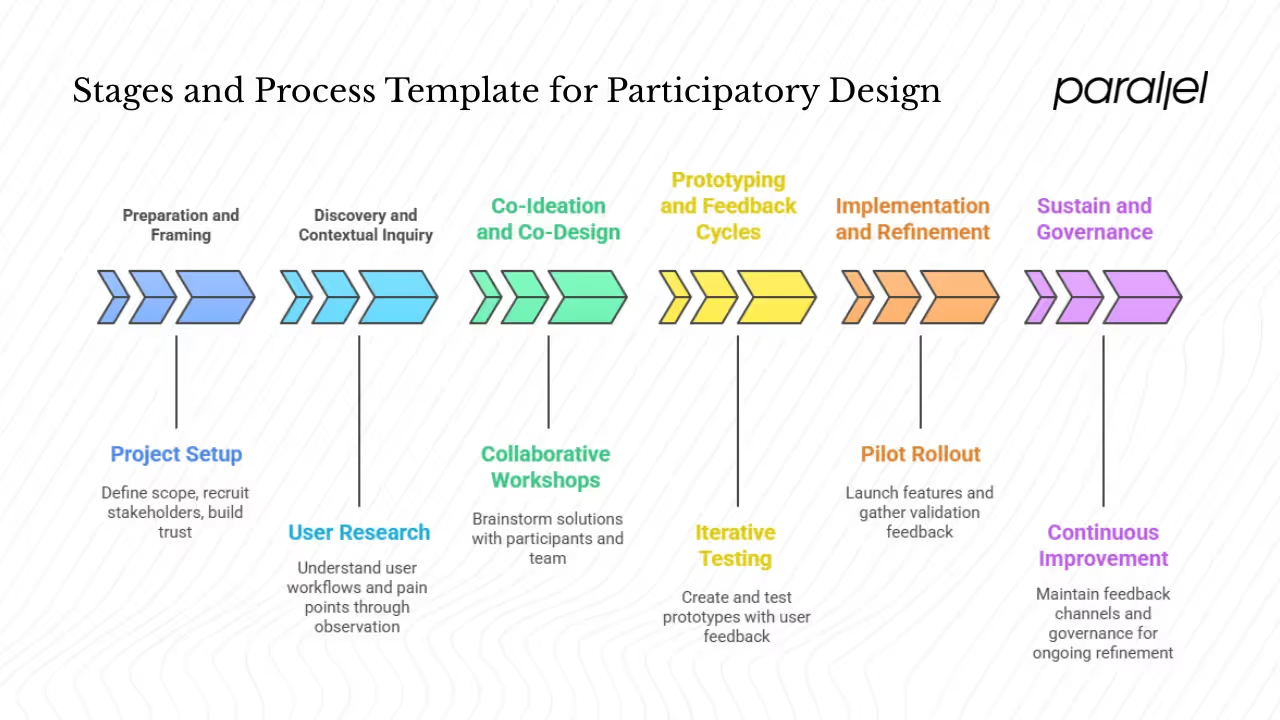

Stages and process template

1) Preparation and framing

Define the scope and goals. Identify which part of the product needs participatory input (e.g., onboarding flow, dashboard layout). Map stakeholders and recruit a cross‑section of participants—end users, domain experts, internal teams. Build trust through initial conversations and clarify expectations. For example, set guidelines about meeting frequency and decision rights so participants know the degree of influence they will have.

2) Discovery and contextual inquiry

Spend time understanding users’ context. Methods include shadowing, contextual interviews, cultural probes and participatory observation. Encourage participants to document their workflows or pain points. The Simprints study emphasises that participatory design draws on users’ socio‑cultural insights and empowers them. This stage yields artifacts like process maps, empathy maps and early hypotheses.

3) Co‑ideation and co‑design

Run structured workshops where participants and team members brainstorm solutions. Techniques include collaborative sketching, experience mapping, storyboarding and design charrettes. Use prompts such as “Imagine a perfect day using this product” to elicit ideas. A 2024 telepractice co‑design project used five workshops with lived‑experience participants to develop a prototype; smaller groups allowed deeper discussion.

4) Prototyping and feedback cycles

Translate ideas into low‑fidelity prototypes—paper sketches, clickable wireframes, role‑play scripts. Test them with participants and refine. The health visualisation tutorial provides a procedural guide for preparing sessions, conducting design activities in different formats and analyzing feedback. Offer initial stimuli rather than blank canvases; participants respond better when they have something concrete to critique.

5) Implementation and refinement

As prototypes mature into working features, keep participants involved through pilot rollouts and validation sessions. Document how feedback influenced decisions so participants see that their input mattered.

6) Sustain and governance

After launch, keep channels open for continuous improvement. This might include community forums, rotating stakeholder councils or regular check‑ins. Governance may require handing over some decision‑making rights to user representatives, particularly in civic or community projects.

Sample techniques and tools

- Workshops and focus groups – For co‑ideation and consensus building.

- Storytelling and experience mapping – Participants recount narratives and map interactions over time.

- Cultural probes – Kits (e.g., diaries, cameras) that participants use to document their context.

- Pluralistic walkthroughs – Mixed groups evaluate usability issues together.

- Generative participatory design – Sessions that encourage participants to generate prototypes, common in e‑health.

- In‑situ design – Designing in the environment where the product will be used.

- Remote co‑design platforms – Use remote collaboration tools for geographically dispersed participants. Many of our sessions involve video calls and shared virtual whiteboards.

- Feedback boards and idea walls – Asynchronous spaces where participants can leave comments and vote.

Sample timeline for a lean project

Adjust this timeline based on product scope and team capacity. Shorter cycles may be possible for narrow features, while a civic project may require months.

Case studies and examples

Simprints: biometric identification in low‑resource settings

Simprints, a non‑profit technology firm, provides fingerprint scanners integrated with mobile apps to improve identity verification in healthcare and microfinance. A study documenting their use of participatory design notes that this approach supports collaborative, community‑based practices and empowers users to take ownership. However, the team struggled to translate human‑centred design toolkits into their technical projects due to the complex realities of low‑resource settings. They found limited guidance on overcoming challenges such as unreliable power, limited connectivity and cultural differences. Through partnerships with local health workers and community members, Simprints adjusted the hardware design, interface and deployment strategy. Participants suggested design tweaks like adding bright indicators for low battery and designing enclosures that resisted dust and humidity. Without this involvement, the product might have been too fragile for rural clinics.

Telepractice co‑design with people with disabilities

A 2024 research project co‑designed a telepractice model for a disability service in Western Australia. Ten experienced experts and staff participated in five workshops, producing a prototype telepractice model for testing. Participants pointed out the value of small groups, accessibility and choice. They also noted tension between ideal features and realistic constraints. The organisational team learned that co‑design introduces messy, time‑consuming dynamics that clash with formal approval processes. Nonetheless, the process generated a model better aligned with clients’ needs and built shared ownership across the organisation.

Health information visualisations

Adriana Arcia and colleagues produced a 2024 tutorial for participatory design sessions aimed at developing health information visualisations. The authors describe participatory design as an increasingly common method that helps ensure visualisations are comprehensible and meaningful to target audiences. They stress that existing guides often lack procedural details and that success depends on practical considerations such as session format and internet‑based data collection. Their guide includes a glossary, consent templates and prompts; it emphasises that the process is iterative and benefits from early stimuli. For example, they found that providing participants with initial graphics to react to, rather than starting from a blank page, leads to more focused feedback.

Parallel’s experience with an onboarding flow

In our work at Parallel, we partnered with a SaaS startup that used machine learning to redesign their onboarding flow for small businesses. The team had built a linear, multi‑step setup wizard and shipped it without engaging users. Adoption stagnated. We proposed a participatory approach: we recruited six customers (owners and finance managers), two support agents and the product manager. In the discovery phase we shadowed them as they signed up, capturing friction points. During co‑ideation workshops we jointly sketched alternate flows, such as progressive disclosure of setup options and contextual tips. Through prototyping and testing we discovered that users preferred to integrate one service at a time and wanted to see immediate value before configuring more. The resulting onboarding allowed customers to start with a single feature and add others later. After launch, sign‑up completion rates increased by 25%, and support tickets about onboarding dropped by half. This experience reinforced the value of participatory design in avoiding speculative features and building trust.

Best practices and tips for startups

- Start small – You don’t have to commit to months of workshops. Pilot participatory methods on a single feature or cycle. After success, expand.

- Motivate participants – Offer incentives (gift cards, recognition, early access) and explain the impact of their involvement. People are more likely to stay engaged if they see how their ideas influence the product.

- Recruit thoughtfully – Balance early adopters with less vocal users. Use stakeholder mapping to identify roles, demographics and outliers. Partnerships with community organisations can help reach under‑represented groups.

- Manage expectations – Be honest about what’s up for discussion and what’s constrained (e.g., regulatory requirements). Participants appreciate transparency and will adjust their suggestions accordingly.

- Facilitator matters – Invest in training or hire a facilitator experienced in group dynamics. They should create a safe environment, encourage quieter voices and synthesise ideas.

- Document decisions – Keep a clear record of feedback, decisions and rationale. Share updates with participants so they feel heard and understand why certain suggestions were incorporated or deferred.

- Integrate with your roadmap – Consider participatory insights as part of your product backlog. Prioritise improvements based on impact and feasibility and schedule them in sprints.

- Hybrid methods – Combine in‑person sessions with remote tools when participants are geographically dispersed. Asynchronous feedback boards can supplement synchronous workshops.

- Ethical considerations – Obtain informed consent, respect privacy and ensure participants’ contributions are acknowledged. Be aware of power dynamics; avoid exploitative practices.

- Scale with growth – As your team grows, make participatory design part of how you work. Create roles or committees responsible for ongoing stakeholder engagement.

Metrics and evaluation

How do you know if participatory design “worked”? Consider qualitative and quantitative indicators:

- Qualitative feedback – Ask participants whether they felt valued and whether their ideas influenced the outcome. Look for signs of satisfaction and empowerment.

- Insight richness – Evaluate the depth and novelty of insights collected. Did participatory sessions uncover issues that traditional methods missed?

- Feature adoption – Track usage metrics after launch. Higher adoption or reduced support requests can signal a better fit.

- Reduction in fixes – Measure the number of design changes required after release. Participatory projects often reduce post‑launch rework.

- Idea‑to‑implementation ratio – Count how many participant suggestions were implemented versus discarded. A high ratio indicates efficient translation of feedback.

- Time to release – Track any delays introduced. Participatory design can extend timelines; monitor whether the benefits justify the extra time.

- Participant retention – For long projects, assess whether stakeholders stay engaged. Drop‑off rates might indicate fatigue or unclear value.

Decision guide: when to choose participatory design

Ask yourself:

- Is user involvement critical? – If the problem deeply affects users’ workflow or wellbeing, co‑creating is beneficial.

- Can you access participants? – Without access to willing participants, participatory design will struggle.

- Do you have time and budget? – Iteration requires resources. For low‑stakes features with minimal impact, quick testing may suffice.

- Are there multiple stakeholder groups? – Projects with regulators, operators and end users benefit from shared decision‑making.

- Are you redesigning a high‑impact system? – Systems that affect public services, healthcare or safety warrant participatory approaches.

If you answer “no” to several, consider lighter methods: quick interviews, usability tests, analytics or A/B experiments. You can still adopt a participatory mindset—seeking input early and often—without a full programme.

Conclusion

Founders and product leaders often ask what participatory design is and why it matters when time and capital are scarce. Participatory design isn’t about giving up control; it’s about reducing guesswork by involving those who will live with your product. Its origins in Scandinavian workplace democracy remind us that technology can empower or alienate. By broadening involvement, encouraging shared creation, representing varied voices and iterating openly, we move from designing for to designing with. The result is not just more user‑friendly products but stronger partnerships and deeper insights. Try a small participatory session in your next sprint—invite two customers to sketch solutions with you—and see how it changes your perspective.

FAQ

1) What do you mean by participatory design?

Participatory design is a philosophy and set of methods that involve end users and stakeholders as active contributors throughout the design process. It emphasises collaboration, empowerment, iteration and contextual understanding so that products meet real needs and reduce professional bias.

2) What is a participant design?

People sometimes mis‑state the term. They usually mean participatory design: a process where participants co‑create solutions. There is no separate concept called “participant design.”

3) What is participatory design vs co‑design?

Co‑design usually refers to joint ideation sessions; participatory design spans a wider process including discovery, recruitment, prototyping and governance. Co‑design is often a component of participatory design.

4) What is participatory development?

Participatory development refers to community‑led planning and implementation, often used in global development projects. It shares the philosophy of local ownership with participatory design but operates at a larger, socio‑economic scale.

5) How many participants do I need?

It depends on your goals. For focused features, 4–6 participants may provide depth. For projects with broad impact, recruit a cross‑section of users, staff and other stakeholders. Ensure you include less vocal voices to avoid skewed insights.

6) How do I recruit participants?

Map stakeholders, reach out through networks, community groups and user panels. Offer incentives and be transparent about expectations and time commitments. Partnerships with advocacy groups or industry associations can broaden your reach.

7) How do I manage conflicting feedback?

Facilitate sessions to surface underlying needs behind conflicting suggestions. Cluster feedback into themes, prioritise based on impact and feasibility and document the rationale for decisions. Communicate back to participants so they understand how their input was used.

8) Can we use participatory design remotely?

Yes. Remote workshops, virtual whiteboards and asynchronous feedback tools enable participation across locations. The 2024 tutorial on participatory design for health visualisations includes guidance on internet‑based data collection.

9) Is participatory design time‑consuming?

It does require planning and iteration. However, early involvement often prevents costly rework later. Start with a small pilot to evaluate the return on investment.

.avif)