What Is a Product Brief? Complete Guide (2026)

Understand the purpose of a product brief, what it should include, and how it aligns teams around product goals and requirements.

Most new products never see the light of day. Data show that roughly 30,000 consumer products launch each year, yet only 40 % reach the market and around 95% fail to generate revenue. Many misfires stem from fuzzy goals, scope creep and teams working at cross‑purposes. After a decade building products for early‑stage SaaS and technology companies, I’ve learned that one document—a product brief—can keep everyone on track. So what is a product brief, and how can it help early‑stage founders and product teams? This article explains the concept, breaks down its elements and offers practical advice to avoid common pitfalls.

What is a product brief? Definition and context

A product brief (sometimes called a product specification) is a short document that outlines the purpose, goals and main details of a new product or feature. When someone asks what is a product brief, the answer is that it defines the product’s goals, attributes and direction, and outlines the requirements and information needed by the team to build it. Softkraft adds that it’s developed at the initial stage of product development and serves as a single source of truth, helping product teams understand user requirements and plan work. ProductFolio describes it as a blueprint that contains vital information such as business needs and goals. In practice, it’s a concise narrative that answers three questions: what is being built, why it matters and how success will be measured.

A product brief differs from a product requirements document (PRD) or a roadmap. A PRD is usually more detailed, specifying functional and technical requirements; a roadmap lays out the timeline and sequence of releases. The brief sits upstream of these documents: it clarifies the vision and problem to solve, which then informs the PRD and roadmap. It also differs from a feature spec, which drills into a single feature’s technical details. You create a product brief during the ideation or planning phase before development starts.

Why it matters for startups and product/design leaders

In early‑stage companies, resources are tight and teams are small. A clear product brief brings everyone together by giving a shared vision and well‑defined scope. For startups and product/design leaders, understanding what is a product brief clarifies roles and expectations. Softkraft notes that a brief provides context across departments and helps teams move toward a common goal. When our studio has partnered with founders, we’ve seen how a brief cuts down on unnecessary meetings and rework because the team can reference a single document instead of guessing. ProductPlan points out that a brief influences product quality, sets the pace and keeps team members on the same page, reducing surprises. It also encourages collaboration across disciplines because it’s a living document updated as priorities change.

In the absence of a brief, projects often drift. Statistics from Visual Planning show that 47 % of agile projects overrun budgets, miss deadlines or result in unhappy customers. Poor planning and lack of communication are among the leading causes. By contrast, a product brief clarifies the “why” behind every decision, guiding trade‑offs on features and budget. It helps founders decide whether to cut a feature or push a deadline. On top of that, investing time in this document builds trust with stakeholders; as Aha! notes, engaging colleagues early and often to gather insights ensures buy‑in across engineering, design, marketing and sales

Essential elements of a product brief

A strong brief covers enough detail to guide development without turning into a novel. We usually cover these essentials:

1) Project overview: State in plain language what the product or feature is, the problem it solves and the vision behind it. A sentence or two is enough to set context for everyone.

2) Audience & personas: Describe who will use the product and what they need. Personas are fictional, research‑backed representations of your users. They promote empathy and keep features grounded in real goals.

3) Features & design requirements: Outline the primary features—what must be included versus what would be nice to have—and mention any broad design considerations like platforms, style and accessibility. This helps prioritise and ensures designers and engineers work toward the same experience.

4) Competition: List major competitors and how you will differentiate from them. A few bullets on positioning, pricing or gaps are enough to identify opportunities.

5) Marketing & constraints: Summarise your positioning, messaging, launch channels and any resource or budget constraints. Including marketing early helps you plan for adoption instead of bolting it on later.

6) Timelines, roles & metrics: Sketch a rough roadmap with major milestones, identify who owns which part and define how success will be measured. Product KPIs should quantify success and guide strategic decisions; use a mix of business, user and development metrics.

As you fill each section, ask yourself: what is a product brief meant to achieve for your team? It should provide clarity and focus so that every decision ties back to the product’s goals.

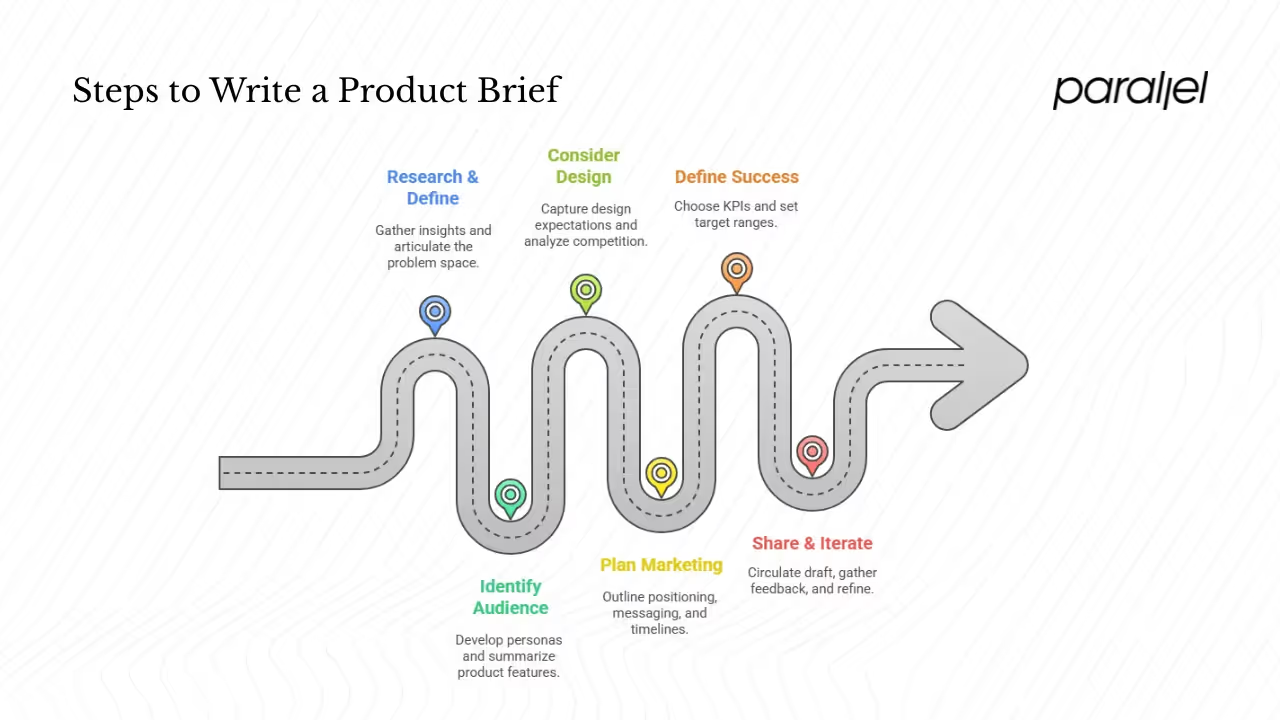

How to write a product brief—step by step

- Research and define the problem: Start by gathering insight through user interviews, surveys and market analysis. Use data (churn rates, conversion metrics) to understand the problem space and articulate the opportunity you’re addressing.

- Identify your audience and describe the product: Turn your research into personas and summarise the product in a couple of sentences. List primary features from the user’s perspective—what must be included versus what can wait.

- Consider design, constraints and competition: Capture major design expectations (platforms, style, accessibility) alongside any technical or resource constraints. Spend time analysing competitors to see what they do well and where gaps exist.

- Plan marketing, timelines and budget: Outline positioning, messaging and launch channels, then draft a rough roadmap with major milestones. Estimate how long each stage will take and be honest about budget and staffing.

- Define success metrics: Choose a handful of KPIs that reflect business and user outcomes—adoption, retention, revenue, defect density—and set target ranges.

- Share, gather feedback and iterate: Circulate the draft among stakeholders, invite questions and suggestions, then refine it. Use version control or a collaborative tool to track changes. Update the document as priorities shift; a product brief should change and grow.

Common pitfalls and best practices

1) Making it too long or too technical: Overly detailed briefs become unreadable. Stick to the why and what; leave the how for technical specs.

2) Leaving assumptions unstated: Teams often omit constraints, which later cause friction. If a feature is optional, state it. If you’re unsure about a market segment, call it out as a research area.

3) Not involving stakeholders early: Waiting until the last minute to consult engineering or marketing leads to pushback. Invite them during the drafting stage so they can voice concerns and bring their expertise.

4) Treating it as static: A brief written once and forgotten quickly loses relevance. Review and update it regularly as you learn more about users, competition and technology.

5) Over‑promising on scope, timelines or resources: It’s tempting to aim high to excite investors or leadership. But unrealistic promises erode trust and lead to burnout. Be honest about what you can deliver.

Example product brief

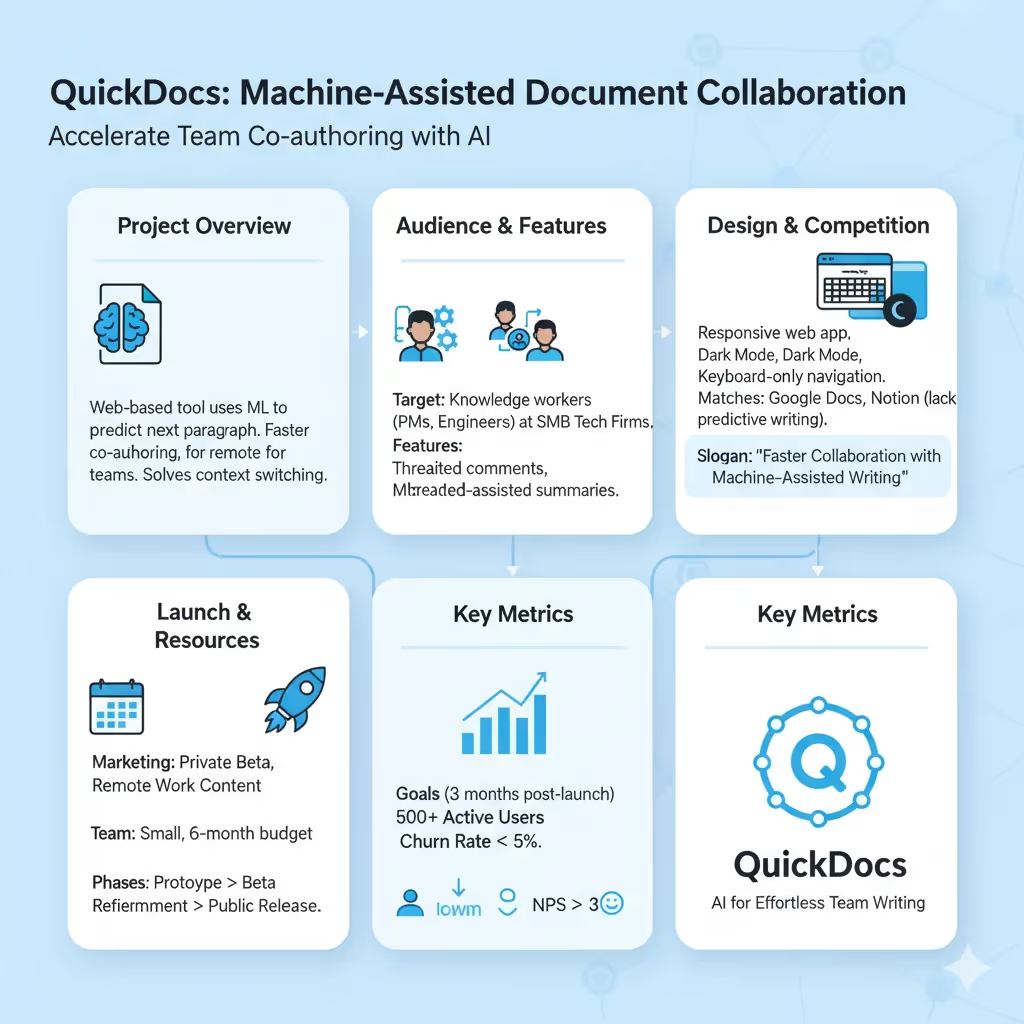

Below is a simplified product brief for a hypothetical SaaS tool called QuickDocs, a machine‑assisted document collaboration platform aimed at distributed teams.

Project overview: QuickDocs is a web‑based tool that uses machine learning to predict the next paragraph in collaborative documents, helping remote teams co‑author faster and maintain consistency. It solves the problem of context switching between individual writing and collaborative editing.

Audience and features: QuickDocs targets knowledge workers at small to mid‑sized tech firms—people like product managers and engineers who want frictionless collaboration. Its main features include real‑time co‑editing with predictive suggestions, threaded comments and machine‑assisted summaries.

Design and competition: The responsive web app will support dark mode and keyboard‑only navigation while matching the company’s colour palette. Competitors such as Google Docs and Notion offer basic collaboration but lack predictive writing, so QuickDocs positions itself as “faster collaboration with machine‑assisted writing.”

Launch and resources: Marketing begins with a private beta and content on remote work. A small team works within a six‑month budget, moving from prototype to beta, refinement and public release.

Metrics: The goal is to reach 500 active users within three months of launch, keep churn below 5 % and achieve a Net Promoter Score above 30.

Performance metrics and how to measure success

Success metrics should tie directly to business and user goals. Atlassian categorises product KPIs into three groups: business performance, customer/user engagement and product development. Business metrics include gross and net revenue, conversion rate and average revenue per user. Customer metrics cover activation rate, retention rate, churn and Net Promoter Score; these indicate whether users find value. Product development metrics—such as time to market, defect density, feature adoption rate and team velocity—measure how efficiently the team delivers work.

Use both leading indicators—such as sign‑ups and daily active users—and lagging indicators like revenue and retention. Set targets, review them regularly and adjust your product, onboarding or timeline based on what the data shows.

Conclusion

Building something new is always risky. The statistics on product failures are sobering, but they’re not destiny. A concise product brief can bring clarity, help teams make informed trade‑offs and keep everyone pointed in the same direction. Start crafting your brief early, share it widely and update it as you learn. It’s a small investment that pays huge dividends.

You now know what is a product brief and why it matters. Put the concept to work on your next project.

FAQ

1) What is a product brief?

A product brief is a concise document that outlines the purpose, goals, audience and main features of a new product. It serves as a guiding reference, capturing the essence of what you’re building and why.

2) How long should a product brief be?

Aim for one to three pages—enough to communicate the vision without burying the reader in detail. Save technical specifics for separate documents.

3) Why do people ask about product briefs?

Because the term can feel abstract. Knowing what is a product brief—who writes it, when to use it and how detailed it should be—helps teams adopt the practice confidently.

4) What do you mean by product briefly?

It’s simply a request for a short description of a product, not for a product brief. If someone says “describe your product briefly,” they want an elevator pitch.

5) What are brief examples?

They include documents like the QuickDocs example above—concise outlines of purpose, audience, features and metrics often distilled into a page or two.

6) Who is responsible for writing a product brief?

The product manager or founder usually drafts it because they own the vision, but engineers, designers and marketers add details and challenge assumptions.

7) When should you update a product brief?

Whenever new information affects scope or direction—after user testing, market shifts or funding changes. A living brief reflects the latest thinking and keeps the team on the same page.

8) How detailed should design requirements be in a product brief?

Keep them general: specify the platforms, style guidelines and accessibility expectations but avoid pixel‑perfect specs. Detailed UI documentation can follow in a separate design spec.

.avif)