What Is Product Mix? Definition and Examples (2026)

Discover what product mix is and how it refers to the range of products a company offers, helping businesses diversify and meet different market needs.

When founders and product leaders at early‑stage startups grapple with what to build next, they often assume that their offering is a single, indivisible product. In practice, they’re making decisions about a product mix: the combined portfolio of lines, versions and tiers they bring to market. Your mix influences everything from brand perception to operational complexity. Taking a moment to map it out can prevent resource‑splitting errors and open up clearer paths to growth. In this article we’ll define the concept, unpack its dimensions—breadth, length, depth and consistency—and explore real‑world examples. We’ll then look at strategies for expanding, pruning and modernising your mix, consider how to analyse it, flag common pitfalls and answer frequently asked questions.

What Is Product Mix?

A product mix is the complete set of products and services a company offers to its customers. Corporate Finance Institute explains that the mix, also called a product assortment or product portfolio, encompasses every line and item a firm sells. Airfocus defines it similarly: all the product lines and items available for sale. For early‑stage teams, the distinction between a product and the overall mix matters. You may start with one product, but once you add add‑ons, modules or tiers, you’re effectively managing a portfolio with its own dynamics. Clarity about the offering helps you decide what to build, improve or sunset.

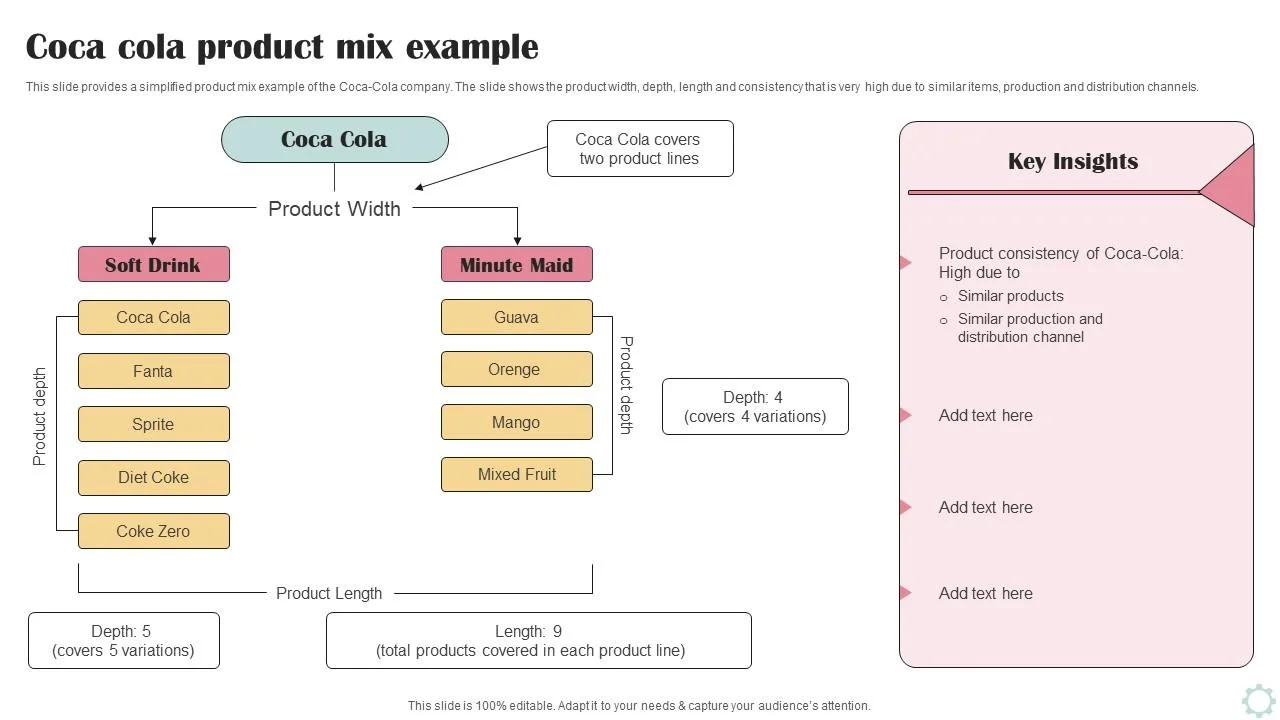

Such a mix consists of product lines, which are groups of related items or services. Within each line are individual product items. A can of Coca‑Cola is an item; all Coca‑Cola branded beverages make up a line; the company’s beverage and juice lines together form the Coca‑Cola mix. This nesting matters because decisions about one line (for instance, adding a new flavour) can affect the overall mix through production and distribution.

Key associated terms

- Product lines: sets of closely related products that perform similar functions or target similar users. They’re the building blocks of a portfolio.

- Product portfolio: another term for a company’s entire collection of products and services. It’s synonymous with this concept, though “portfolio” is often used when discussing strategic allocation of resources across lines.

- Product assortment: commonly used in retail contexts, it refers to the selection of goods and services a business makes available. Airfocus treats it as interchangeable with this concept.

- Product variety: the combination of breadth and depth in a mix. A company with many lines and numerous variants per line has high variety.

- Market offerings: all products, services and experiences a firm offers to a market. Market offerings provide the external view of the mix; internally, product managers need to understand how offerings fit into lines and the mix as a whole.

Understanding these terms ensures everyone on your team speaks the same language when discussing roadmap trade‑offs.

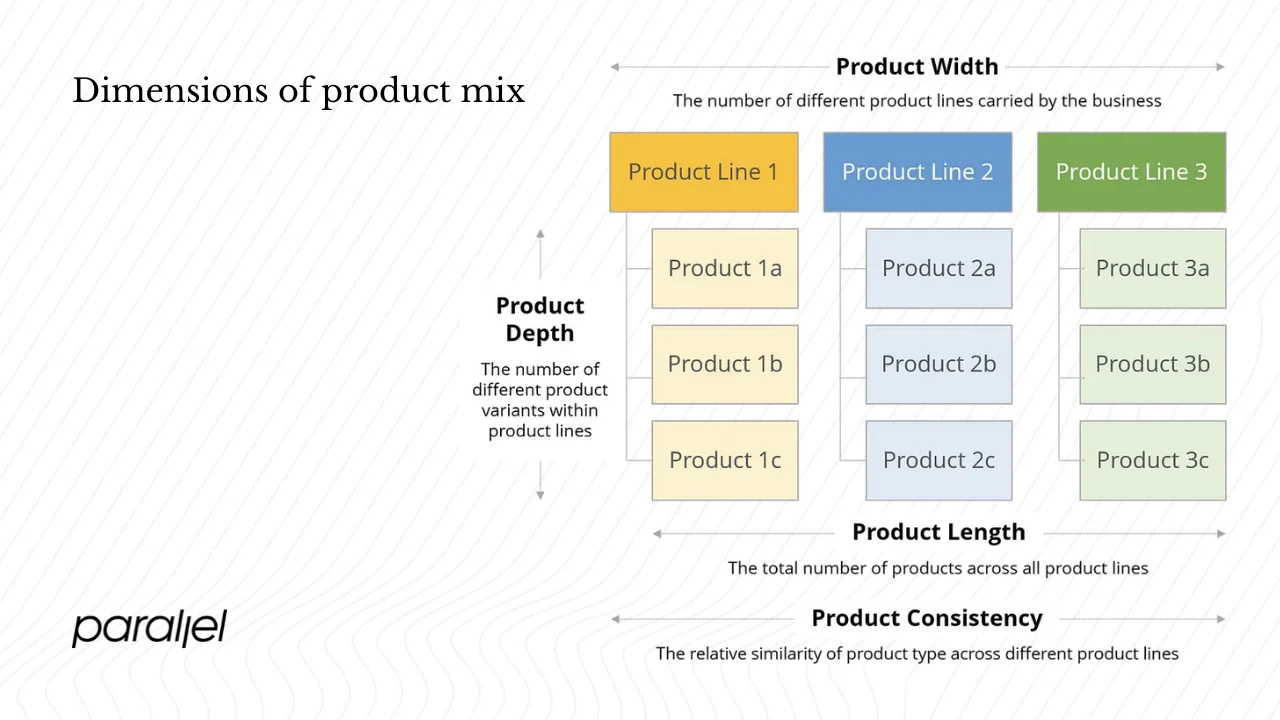

Dimensions of your mix

This mix isn’t a single number but a set of dimensions you can adjust. Mastering these dimensions gives design and product teams levers for growth and simplification.

1) Breadth / width

Breadth (or width) refers to the number of distinct product lines a company offers. If a firm sells smartphones, tablets and wearables, it has a breadth of three. Shopify uses Nestlé’s business to illustrate width: the food giant’s seven lines include beverages, cereals, chocolates, milk products and more. Greater breadth allows you to address different market segments but increases complexity in manufacturing, marketing and distribution. For startups, adding a new line should be a deliberate choice; each line introduces overhead and may dilute focus.

2) Length

Length is the total number of products (items) across all lines in the mix. A car company with two lines and three models in each line has a length of six. Length reflects inventory and support obligations. Shopify notes that Nestlé sells around 10,000 items across its seven lines. A long mix can serve more niches but demands more resources. For early‑stage SaaS teams, length increases as you offer multiple modules, each with its own feature set and version history.

3) Depth

Depth measures the number of variants within a product line. Variants may differ by size, flavour, feature set or pricing tier. Userpilot describes depth as the variety within each line, such as different plans for a SaaS product. Offering depth enables upsell opportunities, segmentation and personalised experiences. In the SaaS world, depth often comes first: a startup launches a core product and then introduces Basic, Pro and Enterprise tiers. Userpilot notes that Semrush expanded its core SEO platform into a suite of analytics and marketing products, deepening its mix to serve varied customer needs.

4) Consistency

Consistency is how closely related product lines are in terms of their use, production and distribution channels. High consistency means lines share processes and brand attributes, like Coca‑Cola’s beverage lines. Low consistency denotes diversification into unrelated categories (e.g., a smartphone maker entering home appliances). Consistency influences brand perception and operational efficiency. Shopify cautions that while inconsistent mixes can diversify revenue, they may dilute brand identity and stretch operational expertise. Startups usually benefit from a high degree of consistency because it allows shared infrastructure and messaging.

5) Bringing dimensions together

Imagine your portfolio as a four‑column matrix: width lists the number of lines, length counts total products, depth captures variants per line and consistency rates how similar those lines are. The combination describes your portfolio’s shape. A company with few lines but many variants (high depth) can tailor products to different segments while keeping operations focused. Conversely, a business with many lines (high width) but few variants has a broad but shallow offering. Product variety—the sum of breadth and depth—helps you visualise how many choices customers face.

The table below summarises three examples that illustrate how width, length, depth and consistency interact. We’ll revisit these examples later.

| Example | Lines & items (width & length) | Variants & consistency (depth & consistency) |

|---|---|---|

| Coca-Cola | Two lines (soft drinks and juices); about ten beverages across both lines | Six soft-drink variants and four juice variants; high consistency because all products are beverages |

| SaaS platform | Three lines (core SEO tool, analytics module, content module); six modules total | Basic/Pro/Enterprise tiers for each line; medium consistency since the lines share a technology base but serve different functions |

| Hypothetical startup | Begins with one line (a productivity app) and later adds a second line (integrations); starts with one item and later expands to three | Free, Basic and Pro tiers within each line; high consistency at first, becoming moderate as new lines are added |

Below the table is a bar chart visualising these dimensions across the three examples:

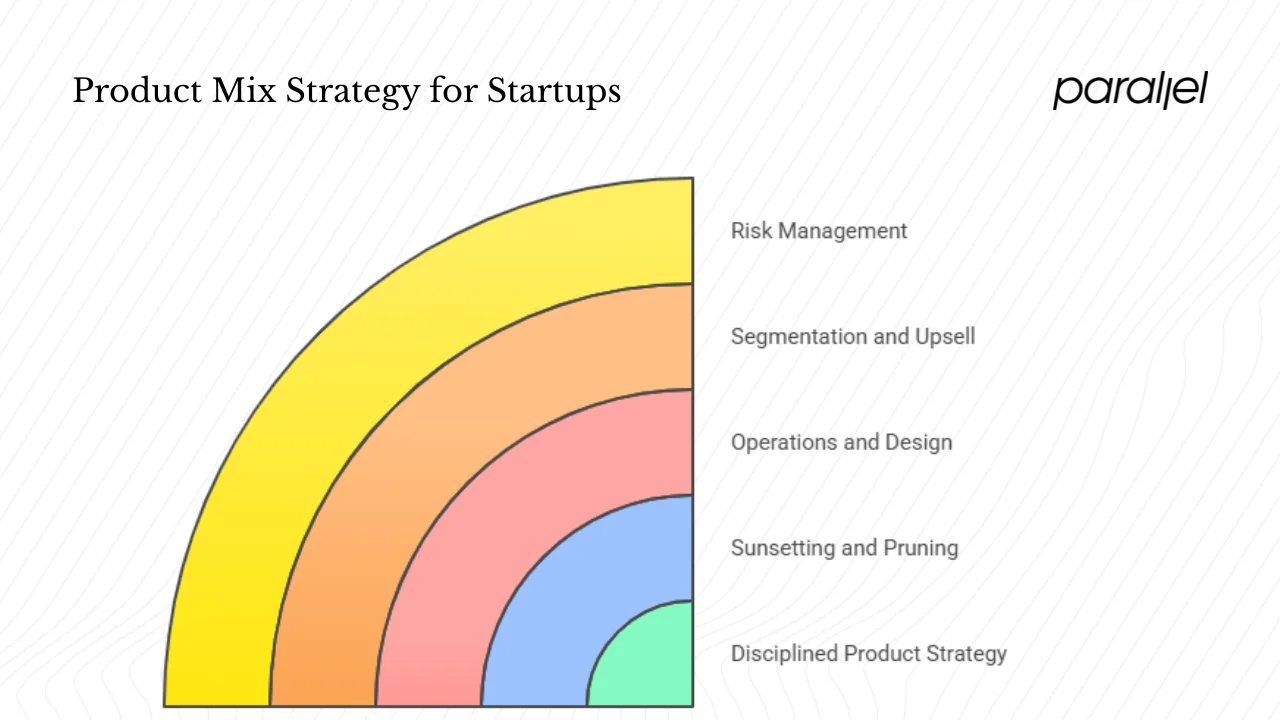

Why your mix matters for early‑stage startups and product teams

When you’re early in your journey, it’s tempting to think you have just one product. But as soon as you add a paid plan, a free tier or an add‑on, you’ve diversified your mix. Understanding your collection helps you decide where to invest limited resources and when to restrain yourself. Here are a few reasons it matters:

- Portfolio thinking: As your company evolves from an MVP to multiple offerings, you’re no longer managing a single asset. You’re orchestrating a portfolio of lines and variants. ProductPlan notes that a portfolio strategy helps focus resources on offerings with the greatest potential for growth and revenue.

- Risk management: Having more than one line can diversify revenue. CFI emphasises that expanding width or depth reduces dependence on one product. Conversely, unnecessary diversification can hurt brand image. Knowing your portfolio lets you balance diversification with focus.

- Segmentation and upsell: SaaS teams often start by deepening an existing line with tiers. Depth allows segmentation and pricing strategies tailored to different customer needs. Invesp’s research shows that tiered pricing remains the most widely adopted model, with companies offering an average of 3.5 tiers. Without a clear view of your offering, you might neglect opportunities to upsell or cross‑sell.

- Operations and design: Each new line or variant introduces design and operational overhead. Maintaining consistency across multiple products—interface patterns, brand voice, support processes—takes work. Shopify explains that inconsistent mixes risk brand dilution and increased distribution complexity.

- Sunsetting and pruning: For every product you add, you should consider what you might drop. A contraction strategy can free up focus for the core offering. Product School advises removing under‑used lines to concentrate resources on more promising products.

For founders and PMs, treating your portfolio as a mix encourages disciplined product strategy: building what matters, deepening where there’s traction, and pruning where there isn’t.

Product mix examples

Concrete examples make abstract concepts tangible. Below are three cases illustrating how different organisations manage their portfolios.

Coca‑Cola (B2C)

The Corporate Finance Institute uses Coca‑Cola to illustrate mix dimensions. In a simplified view, the company has two lines: soft drinks (Coca‑Cola, Fanta, Sprite, Diet Coke, Coke Zero) and juices (Minute Maid’s Guava, Orange, Mango and Mixed Fruit). That gives it a width of two. The length—total items—is ten. Depth is six for soft drinks and four for juice, showing multiple variations within each line. Because all lines fall under beverages, the mix has high consistency. This high consistency lets Coca‑Cola share production facilities and distribution while promoting a unified brand image.

SaaS context

SaaS companies often start with one core product and expand by adding variants and complementary lines. Userpilot highlights Procter & Gamble (P&G) as an example of a consumer goods company with a wide mix: beauty and grooming, health care and home care lines. Each line contains many products (length) with multiple variations (depth). In the SaaS world, think of a platform like Semrush, which began as an SEO tool and evolved into a suite of analytics, advertising and content products. Here the width expanded from one to several lines, while depth increased within each line through various plans and add‑ons. Invesp reports that 38% of SaaS companies bill based on use and an average of 3.5 tiers is common. This illustrates how depth and pricing strategies intertwine.

Another case is Apple. Dovetail’s example shows four product lines—iPhone, iPad, Mac and AirPods—and multiple variations within each line. The depth of the iPhone line alone includes models across generations and storage capacities. Apple’s mix has high consistency because all products are technology devices sharing design language and ecosystems.

Hypothetical startup

Consider a small productivity‑app startup. At launch, there is one product line: the core task manager. The MVP has a free tier and a paid tier, giving a depth of two and a width of one. In year two, the team introduces a collaboration module, creating a second line (width becomes two). Each line now has Basic and Pro tiers, increasing depth. Later, usage data shows the collaboration module is seldom used; the team decides to sunset it. The mix contracts back to one line but retains depth through multiple plans. This evolution illustrates how breadth, depth and length can ebb and flow based on user feedback and resource constraints.

In our own work at Parallel, we’ve seen AI/SaaS teams trip up when they add modules without mapping the impact on their mix. In one case, a startup built three ancillary tools alongside its core platform. Each tool demanded separate UI patterns, onboarding flows and support. The combined length and depth overwhelmed the small team and slowed iteration. When they refocused on a single line with tiered plans, engagement and development velocity improved.

Strategies & how to use them

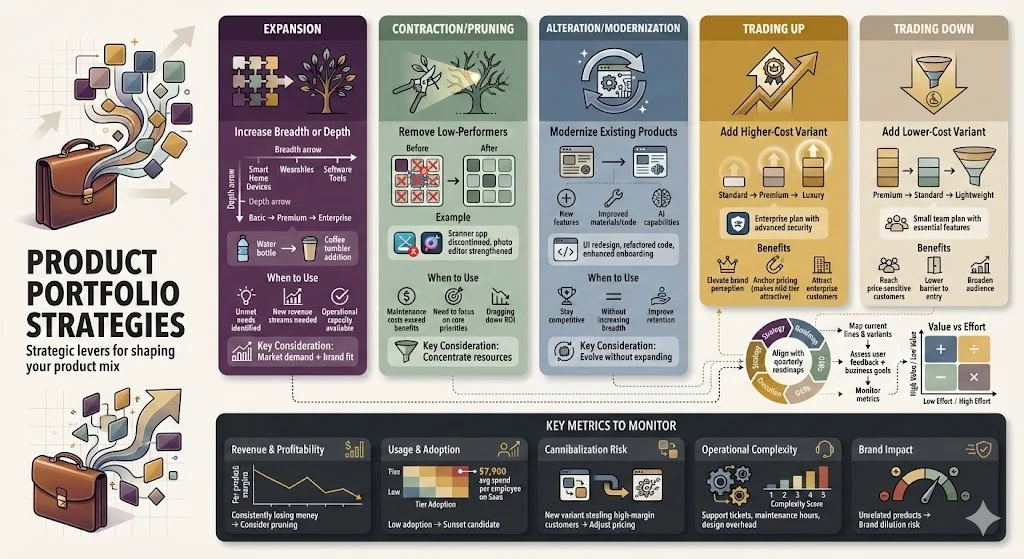

Crafting your portfolio isn’t just about counting products; it’s about choosing strategic directions. ProductPlan outlines several levers—expansion, contraction, improving existing products and differentiation—that companies use to shape their portfolios. Shopify and Product School echo similar strategies. Below are key approaches and when to apply them.

1) Expansion (increase breadth or depth)

Expansion involves adding new product lines or variants. Shopify describes launching coffee tumblers as an expansion for a water bottle company. In SaaS, this could mean adding a new module (breadth) or introducing a Premium tier (depth). Expansion can open new revenue streams and address unmet needs, but it requires careful evaluation of market demand, operational capacity and brand fit.

2) Contraction / pruning

Contraction means removing low‑performing lines or variants to concentrate resources. Airfocus notes that shrinking the mix can improve return on investment by cutting products that drag down overall performance. Product School gives the example of a digital platform discontinuing an underused scanner app to focus on its photo‑editing line. Startups should consider pruning when maintenance costs exceed benefits or when a line distracts from core priorities.

3) Alteration / modernization

Instead of adding or removing lines, you can modernise existing products. Shopify calls this modernization—updating existing items with new features, improved materials or generative AI capabilities. ProductPlan refers to it as changing an existing product. For SaaS teams, modernization might involve refactoring code, redesigning UI or enhancing onboarding to improve retention. This strategy helps stay competitive without increasing breadth.

4) Diversification, trading up and trading down

Diversification involves entering new markets or categories. ProductPlan describes trading up—adding a higher‑cost variant to elevate brand perception and encouraging purchase of mid‑tier products—and trading down, introducing a lower‑cost variant to reach price‑sensitive customersproductplan.com. Shopify echoes these strategies, highlighting how adding premium or budget versions can shift perceptions and broaden your audience. For a SaaS startup, trading up could mean offering an Enterprise plan with advanced security, while trading down might involve a lightweight plan for small teams.

5) Aligning with product management frameworks

A portfolio strategy should tie into your roadmapping and prioritisation processes. ProductPlan emphasises that a roadmap defines the vision and major milestones needed to reach strategic goals. Aligning your portfolio with this roadmap ensures you invest in lines and variants that support your objectives. Tools like OKRs and value versus effort matrices help prioritise which expansions or contractions to pursue. In practice, we advise teams to revisit their offering when planning quarterly roadmaps: map your lines, variants and consistency levels, then assess where user feedback or business goals suggest additions or removals.

6) Metrics and signals to monitor

Deciding whether to expand, contract or modernise requires data. Useful metrics include:

- Revenue and profitability per line: Identify which lines and variants drive margin. If a line consistently loses money, consider pruning.

- Usage and adoption: Track active users or usage frequency for each variant. Invesp reports that businesses spend an average of US$7,900 per employee on SaaS tools and that SaaS costs have risen about 8.7% year‑over‑year. High usage on one tier might justify deeper investment, while low adoption may signal the need to sunset.

- Cannibalisation risk: Monitor whether a new variant shifts customers away from higher‑margin versions. Tiered pricing can trigger cannibalisation if not designed carefully.

- Operational complexity: Estimate support, maintenance and design overhead per product. More lines and variants increase complexity.

- Brand impact: Use surveys or brand tracking to understand if new lines align with your positioning. CFI warns that adding unrelated products can harm brand image.

How to identify and analyse your portfolio

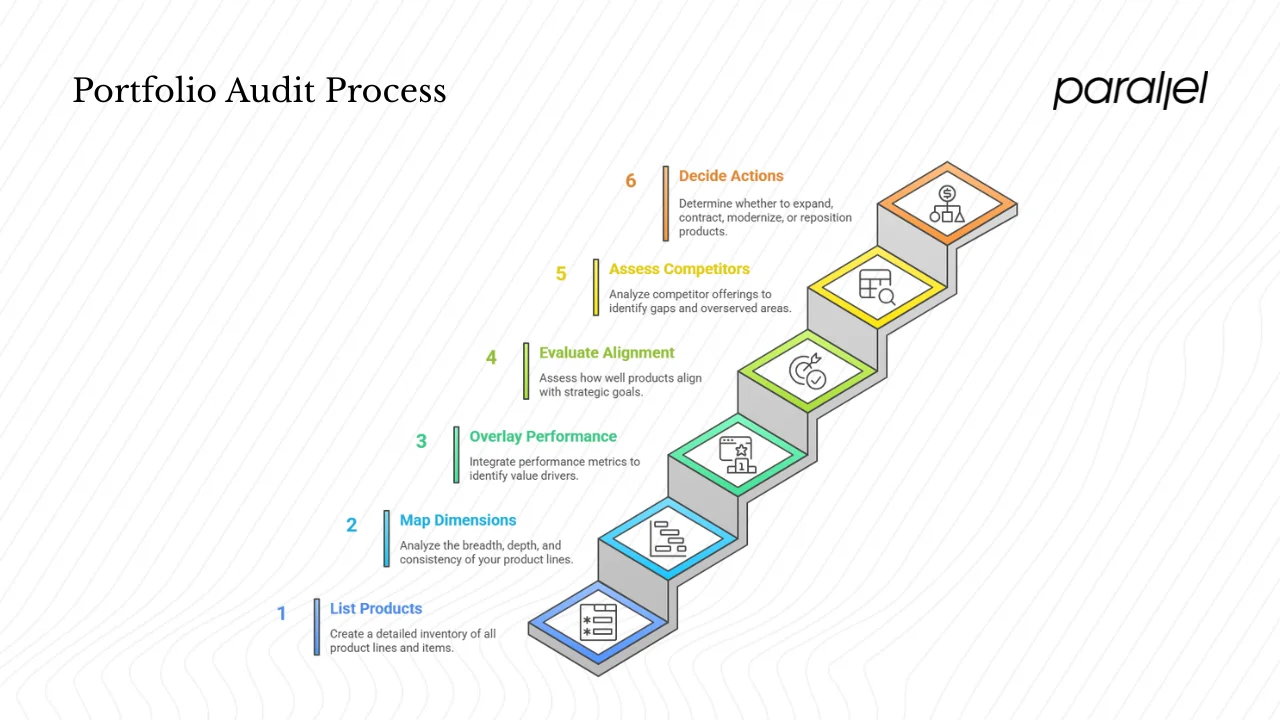

To make informed decisions about your portfolio, you need a clear inventory of what you offer and how it performs. Here’s a simple audit process:

- List all product lines and items. Create a spreadsheet with each line and every variant. Include details such as launch date, target segment and pricing.

- Map the dimensions. Add columns for width (number of lines), length (total items), depth (variants per line) and consistency (rating or notes on how closely related the lines are). Use the matrix from Section 2 as a guide.

- Overlay performance data. Include metrics like revenue, gross margin, active users and customer satisfaction for each item. For SaaS companies, note usage levels and churn. This helps you see which parts of the mix drive value.

- Evaluate alignment with strategy. Compare each line and variant against your product vision and OKRs. Does this offering serve your target segments? Is it essential for your roadmap?

- Assess competitor mixes. Airfocus suggests identifying direct, indirect and replacement competitors, analysing their top products and then mapping their breadth, depth and target audiences. This can reveal gaps in your own portfolio or overserved areas where differentiation is hard.

- Decide on actions. Based on usage and strategic alignment, choose whether to expand, contract, modernise or reposition. Document your rationale so future teams understand why decisions were made.

During this audit, keep an eye on variety. A high variety may look impressive but can overwhelm users and teams. Many startups benefit from focusing on a narrow but deep mix early on.

Common mistakes and pitfalls in mix management

- Adding too many lines too early: New founders often launch additional products to chase every opportunity. This spreads resources thin, dilutes focus and slows iteration. Stick to a narrow portfolio until the core line achieves product‑market fit.

- Low consistency leading to brand confusion: Introducing unrelated products can confuse customers. Shopify warns that inconsistent assortments may dilute brand identity. Maintain coherence, especially when your brand is still forming.

- Ignoring complexity costs: Every new variant demands design work, testing, support and marketing. Underestimating these costs leads to technical debt and user experience problems. A leaner portfolio is often easier to polish.

- Cannibalisation: Without careful positioning, new variants can cannibalise profitable offerings. For example, a budget tier may attract existing customers from mid‑tier plans. Pricing and feature differentiation should minimise cannibalisation.

- Lack of data‑driven decisions: Expanding or pruning based on gut feeling can lead to misalignment with customer needs. Use performance data, user research and competitor analysis before changing your offering.

Conclusion

Your product mix is more than a list of products—it’s a strategic tool that shapes how your company grows, competes and serves customers. By understanding the dimensions of breadth, length, depth and consistency, you gain levers to expand or contract thoughtfully. Recognising that even startups have some form of portfolio—even if it’s just a core product with multiple plans—prevents blind spots and helps you avoid complexity traps. Strategies such as expansion, contraction, modernization and trading up or down provide options for adapting to market needs. Auditing and analysing your offering with data ensures you invest in the right lines and variants while sunsetting those that no longer serve your goals. In our work with AI and SaaS teams, those who take this portfolio view build more resilient businesses and deliver better experiences. If you haven’t mapped your portfolio yet, now is the time to do it and use it as a compass for future design and product decisions.

FAQ

1. What is the meaning of product mix?

It’s the complete range of product lines and individual items a company offers to its customers. This collection is sometimes called a product assortment or product portfolio.

2. What are the four components of a product mix?

The four dimensions are width (number of product lines), length (total number of items), depth (variants within each line) and consistency (how closely related the lines are).

3. Is Coca‑Cola a product mix?

Not exactly—it’s a brand. The Coca‑Cola Company’s portfolio includes its soft drink line (Coca‑Cola, Fanta, Sprite, Diet Coke, Coke Zero) and its Minute Maid juice line (Guava, Orange, Mango, Mixed Fruit). Together these lines, and other beverages like water, make up the company’s offering.

3. How to identify a product mix?

Start by listing all your product lines and variants in a spreadsheet. Map the width (number of lines), length (total items), depth (variants per line) and consistency (how similar the lines are). Overlay performance metrics like revenue and usage, and compare your portfolio to competitors. This audit will reveal whether you should expand, contract or modernise your offerings.

.avif)