What Is a Product Plan? Complete Guide (2026)

Understand what a product plan is, its components, and how it helps structure development, marketing, and launch activities.

A report by the Founders Forum Group summarizing data from 2024–2025 shows that 90% of startups fail, with 70% failing between years two and five. The same report notes that 42% collapse because they misread market demand—they build something nobody wants. As someone who has worked with dozens of early‑stage software teams, I’ve seen that pattern up close. Brilliant engineers and designers pour months into a product idea only to watch it fizzle because they didn’t have a clear plan. Crafting a product plan isn’t busywork; it’s a survival skill. Without one, teams drift, investors lose faith, and energy is wasted. With a solid plan, the why, who, what, when and how are visible, so everyone can move in the same direction.

This article unpacks what a product plan is and why it matters. I’ll explain the difference between product planning and the plan itself, outline each component of a good plan, share a step‑by‑step approach, illustrate it with an example, and answer common questions. By the end, you’ll have a toolkit for creating your own. My goal is to speak plainly, drawing on research and lived experience.

What is a product plan?

A product plan is a written artifact that connects your vision to execution. It outlines who the product is for, what problems it solves, the features you’ll build, when you’ll build them, and how you’ll know if it’s working. It’s the tangible outcome of a process called product planning.

Product planning vs. the product plan

Product planning is an ongoing process. It involves researching opportunities, making decisions, and adjusting as you learn. ProductPlan defines it as “researching, making decisions, and taking action to develop a successful product”. Pragmatic Institute adds that it is a strategic process that guides a product from idea through launch and continues throughout the product’s life, with the plan evolving as new information arises. In other words, planning is a living process, not a one‑time event.

The product plan is the output of that process. ProductPlan explains that planning results in a clear plan that outlines strategic themes, feature priorities, pricing, timelines and metrics. MindManager differentiates the plan from the roadmap by stating that a product plan clarifies what the product is, who it’s for and why it’s being developed, whereas a roadmap is a visual path to execution. Think of your plan as a narrative document that ties together vision and execution; the roadmap is a visual companion that maps priorities over time.

Why product planning matters

Planning matters because it ties people and resources to a shared purpose. Pragmatic Institute notes that effective planning ensures the product aligns with business goals, meets customer needs, manages resources and risks, and sets clear milestones. Without this structure, teams default to guesswork. I’ve seen engineering teams build features with no clear connection to revenue or retention goals. Marketing teams launch campaigns that fail because the product didn’t address a real pain point. Planning helps unify those efforts around evidence.

Planning also reduces waste. ProductPlan lists getting to market faster and cheaper, improving chances of product success, and establishing credibility among stakeholders as benefits of planning. When you commit to planning, you avoid building features that nobody uses and you maintain discipline in spending.

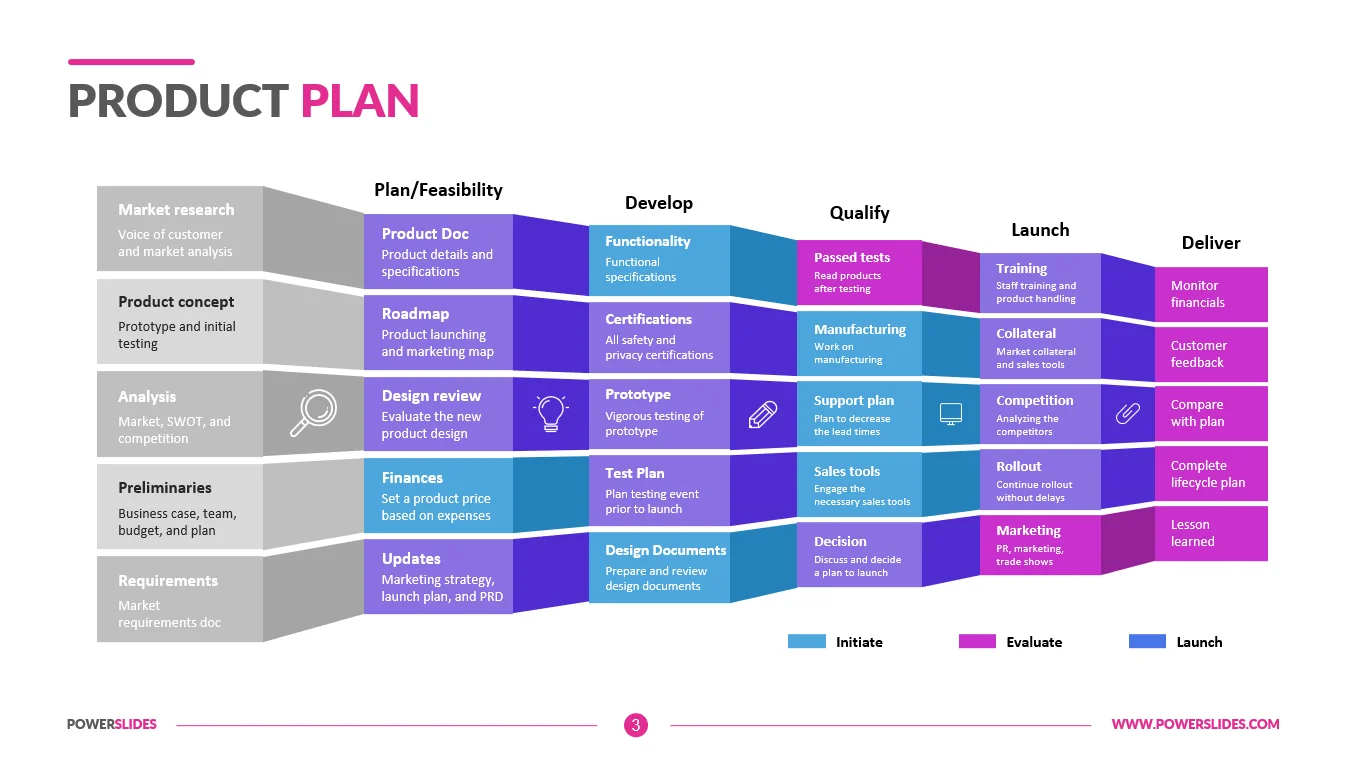

Where it fits in the product lifecycle

A product goes through phases: ideation → planning → delivery → evaluation → iteration. Planning sits between your initial idea and delivery. It draws from discovery research and feeds into your roadmap and go‑to‑market plan. Monday Dev’s guide describes product planning as the process of deciding what to build, when to build it, and how to allocate resources. The same guide contrasts product planning with product strategy (which sets the “why” and “what”) and explains that planning breaks strategy into specific features, timelines, and resource allocations. In practice, planning informs your product strategy and is informed by it. It also interacts with project plans and marketing plans. The boundaries aren’t rigid, but the purpose is clear: planning makes the future real.

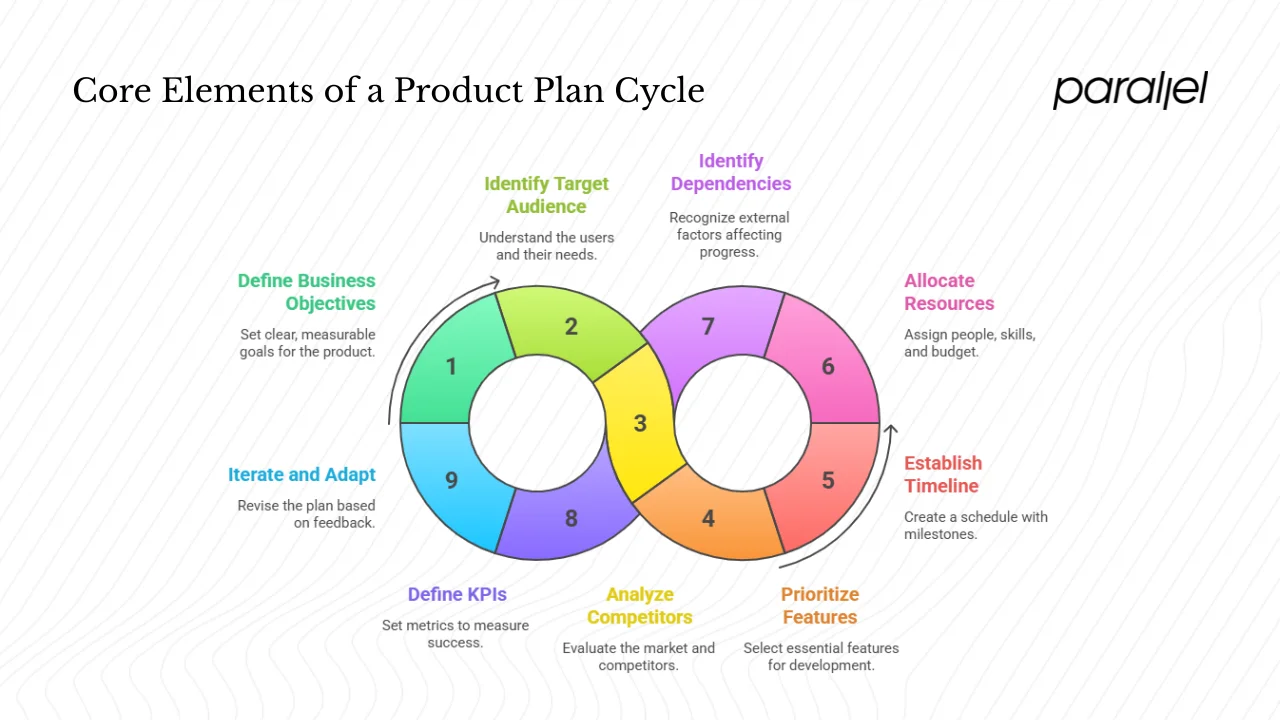

Core elements of a product plan

A useful plan covers several elements. Each addresses a different aspect of why you’re building the product and how you’ll deliver it. Skipping any of them risks drift.

1) Business objectives

Your plan should anchor to clear business outcomes. Ask: what goals does this product serve? Revenue growth? Retention improvement? Engagement? Market share? Pragmatic Institute highlights the need to align the product with business goals and financial objectives. In my experience, vague goals like “grow the user base” lead to confusion. Replace them with measurable targets such as “increase monthly active users by 25% within six months.” Pitfall: being too general or chasing vanity metrics; instead, connect objectives to specific, measurable outcomes.

2) Target audience and personas

A product exists to solve problems for real people. Define who those people are—their roles, goals, pains and context. Monday Dev stresses that the first step in planning is understanding customer needs and market opportunities. Tools like user interviews, surveys and Jobs‑to‑Be‑Done frameworks help clarify these needs. The main pitfall is thinking “everyone” is your customer or creating personas that are too broad. Early‑stage teams often design for themselves rather than for the people who will buy or use the product.

3) Competitor and market analysis

Look outside your bubble. Understand who else is solving the problem, their strengths and weaknesses, pricing and positioning. This analysis helps you differentiate and avoid copying features blindly. Pragmatic Institute lists competitive differentiation as an additional item to consider, emphasising the need to define how your product will stand out. Pitfall: focusing solely on competitors rather than customer needs, which leads to feature parity instead of innovation.

4) Feature prioritisation and scope

Not every idea deserves to be built now. Decide which features are must‑have versus nice‑to‑have. Use prioritisation frameworks like RICE, MoSCoW, or Kano to weigh impact, effort, confidence and risk. ProductPlan says that planning results in prioritised feature lists. The pitfall here is scope creep—trying to build everything at once. Start with a minimal viable product (MVP) that tests core assumptions, then add enhancements.

5) Timeline and milestones

A plan needs a rhythm. Map out phases (e.g., discovery, MVP, beta, launch) and the milestone dates. MindManager notes that a roadmap is a visual representation of tasks and milestones, while Monday Dev emphasises balancing detail and flexibility—near‑term tasks should be well defined while long‑term plans remain open to change. Pitfalls: over‑committing to unrealistic timelines or being too inflexible. Build in buffers for the unexpected.

6) Resource allocation

Assess what people, skills and budgets you need. Identify roles (product manager, designer, engineers), capacity, and budget constraints. Pragmatic Institute lists resource allocation as a key objective, ensuring that time, budget and personnel are managed efficiently. Pitfalls: underestimating effort, ignoring cross‑team dependencies, or assuming people will self‑organise without clear leadership.

7) Dependencies and risks

Every plan has assumptions. List the external factors that could block progress—such as regulatory approvals, third‑party integrations, legal reviews or hardware dependencies. Then identify risks (technical unknowns, market shifts, funding). When I worked with a fintech startup, we didn’t account for a required compliance audit; the product launch slipped by three months. Anticipating dependencies and creating mitigation plans prevents expensive surprises.

8) KPIs and success metrics

Define how you’ll measure success. Tie metrics to your business objectives. For a subscription SaaS product, that might be Daily Active Users, activation rate, retention at 90 days, Net Promoter Score. Pragmatic Institute calls out the need to identify KPIs that measure the product’s impact. Avoid vanity metrics (page views, downloads) that don’t link to value.

9) Iteration and feedback loop

A plan isn’t carved in stone. Build in mechanisms to learn and adapt. Monday Dev emphasises that product planning is ongoing and adapts as you learn. Include feedback channels like user testing, analytics and support tickets. Schedule periodic reviews (e.g., quarterly) to revise the plan based on data. The pitfall here is treating the plan as static or failing to revisit assumptions.

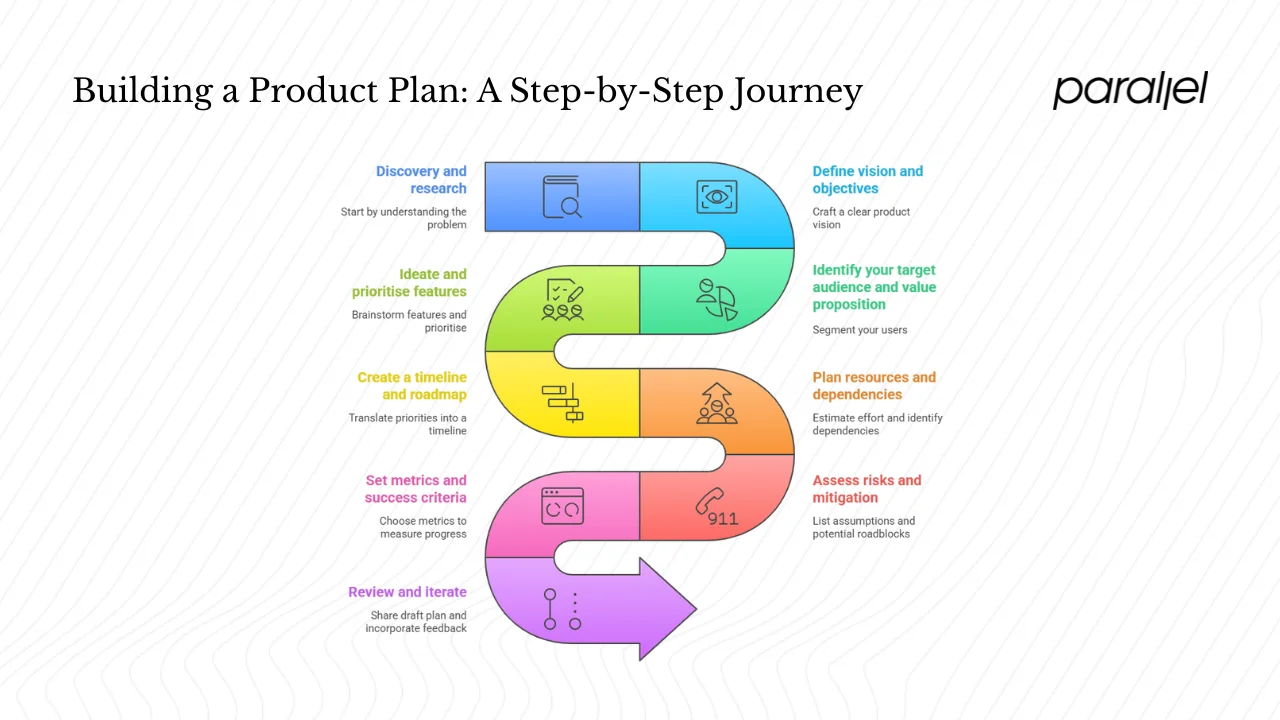

How to build a product plan: step by step

Creating a plan can feel daunting. Here’s a workflow I use with early‑stage founders. Adapt it to your team’s size and maturity.

1. Discovery and research

Start by understanding the problem. Conduct market and user research. Collect qualitative insights through interviews and surveys, and quantitative data through analytics. Monday Dev advises combining primary research (customer interviews, surveys, usability testing) with secondary research (industry trends, competitor analysis). The goal is to validate that there is a real pain point worth solving.

2. Define vision and objectives

Craft a clear product vision in one sentence: what problem you solve and for whom. This becomes your north star. Derive two or three measurable objectives from that vision, such as “reduce onboarding time by 50% within three months.” Map each objective to a business goal (revenue, retention). Pragmatic Institute emphasises aligning the product with business goals and financial objectives. Pitfall: writing vague vision statements full of jargon; instead, be concrete and human.

3. Identify your target audience and value proposition

Segment your users. Create personas or Jobs‑to‑Be‑Done profiles. Document their goals, frustrations and contexts. Then articulate your value proposition—why they should switch to your product. Monday Dev reminds us that product planning bridges the gap between business strategy and product development by balancing customer needs, technical feasibility and financial viability.

4. Ideate and prioritise features

Brainstorm features that address user pain points. Group ideas into themes (e.g., onboarding, analytics, collaboration) and then score them using a framework like RICE (Reach, Impact, Confidence, Effort). Decide which belongs in the MVP and which can wait. This exercise helps manage scope and ensures you focus on high‑impact areas first.

5. Create a timeline and roadmap

Translate your priorities into a timeline. Use phases such as MVP, beta, general availability. Assign rough dates or relative timeframes (Quarter 1, Quarter 2). A UX roadmap is described by Nielsen Norman Group as a strategic, living artifact that aligns a team’s future work and solves problems. This living quality means your timeline should remain flexible; near‑term items are detailed, while far‑term themes can shift.

6. Plan resources and dependencies

Estimate the effort needed for each feature or phase. Consider design, development, testing and marketing. Identify cross‑team dependencies—perhaps your mobile app requires an API from another team, or your legal team must review terms. Allocate budget and staff accordingly.

7. Assess risks and mitigation

List assumptions and potential roadblocks. For each, outline mitigation strategies. For example, if you depend on a third‑party API, plan what you’ll do if the API changes. For regulatory risks, build in time for compliance reviews. This risk register should be revisited regularly as new information emerges.

8. Set metrics and success criteria

For each objective, choose a small set of metrics that measure progress. Define leading indicators (like sign‑ups, activation) and lagging indicators (like churn, revenue). Set targets and thresholds so you know when to celebrate or pivot.

9. Review and iterate

Share your draft plan with stakeholders. Invite feedback from engineers, designers, marketing, sales, and leadership. Incorporate insights, and publish a version everyone can access. Treat the plan as a living document—review it quarterly or whenever the market shifts. As Monday Dev notes, planning is a continuous cycle.

A hypothetical example

Let’s walk through a simple scenario. Imagine you’re building a SaaS tool that helps remote engineering teams track technical debt. Here’s how your plan might look:

- Vision: Help software teams visualise and reduce technical debt so they ship features faster.

- Business objectives: Increase revenue by 20% year‑over‑year; reduce churn to under 5% in the first year.

- Target audience: Engineering managers at mid‑sized SaaS companies; pain points include lack of visibility into code quality and mounting debt.

- Market analysis: Tools like Jira and Asana handle tasks but not technical debt; competitors like CodeClimate focus on code metrics. The gap is actionable workflows for debt.

- Feature prioritisation: Must‑have features: dashboards showing debt by module, alerts for high‑risk areas, integration with GitHub. Nice‑to‑have: predictive models, Slack notifications. Use RICE to score each feature.

- Timeline:

- Quarter 1: Discovery research, MVP development (dashboard and integration).

- Quarter 2: Beta testing with five pilot customers, refine features.

- Quarter 3: Public launch, add alerts and notifications.

- Quarter 1: Discovery research, MVP development (dashboard and integration).

- Resources: Two engineers, one designer, one product manager; budget for GitHub API access.

- Dependencies: Access to customers’ repositories (security and privacy approvals).

- Risks: Low adoption if managers don’t trust automated metrics; mitigation: run workshops with pilot customers.

- Metrics: Activation rate (teams connecting repos), weekly active users, reduction in time spent on code reviews, NPS.

- Feedback loop: Monthly user interviews and analytics review to inform the backlog.

As you can see, the plan answers who, what, why, when, and how. If this team skipped planning, they might have built predictive features before validating the core dashboard.

A tale of two plans

I’ve seen teams succeed because they created a lean plan and revisited it often. Conversely, I worked with a social networking startup that spent nine months building a complex “social graph analysis” feature before confirming whether users needed it. They had no clear objectives or user research. After launch, sign‑ups trickled in, but engagement was low. Had they invested time in research and a simple plan, they could have validated their assumptions earlier and pivoted.

Best practices and tips

Based on research and experience, here are suggestions for creating an effective plan:

- Keep it high‑level at first. Don’t overdesign every feature. Focus on themes and outcomes.

- Use themes or strategic buckets. Organising features into themes prevents your roadmap from becoming a feature wishlist. Nielsen Norman Group notes that roadmaps are often organised by themes and time horizons (Now, Next, Future).

- Involve everyone early. Product managers should engage design, engineering, marketing and sales in planning. This fosters ownership and uncovers dependencies.

- Schedule regular updates. Revisit your plan quarterly or whenever your strategy shifts.

- Visualise it. Use a roadmap tool or simple spreadsheet to make the timeline and priorities visible to all. NNG describes a roadmap as a living artifact that aligns and prioritises future work.

- Communicate trade‑offs. Be transparent about why you’re prioritising some features over others. This builds trust with stakeholders.

- Include buffer time. Product development rarely goes perfectly. Build in slack for unforeseen issues like technical hurdles or regulatory reviews.

- Base decisions on evidence. Use customer data and market research to inform prioritisation rather than gut feel.

- Capture assumptions. Document your hypotheses and revisit them after testing. If an assumption proves false, adjust the plan rather than forcing the product in the wrong direction.

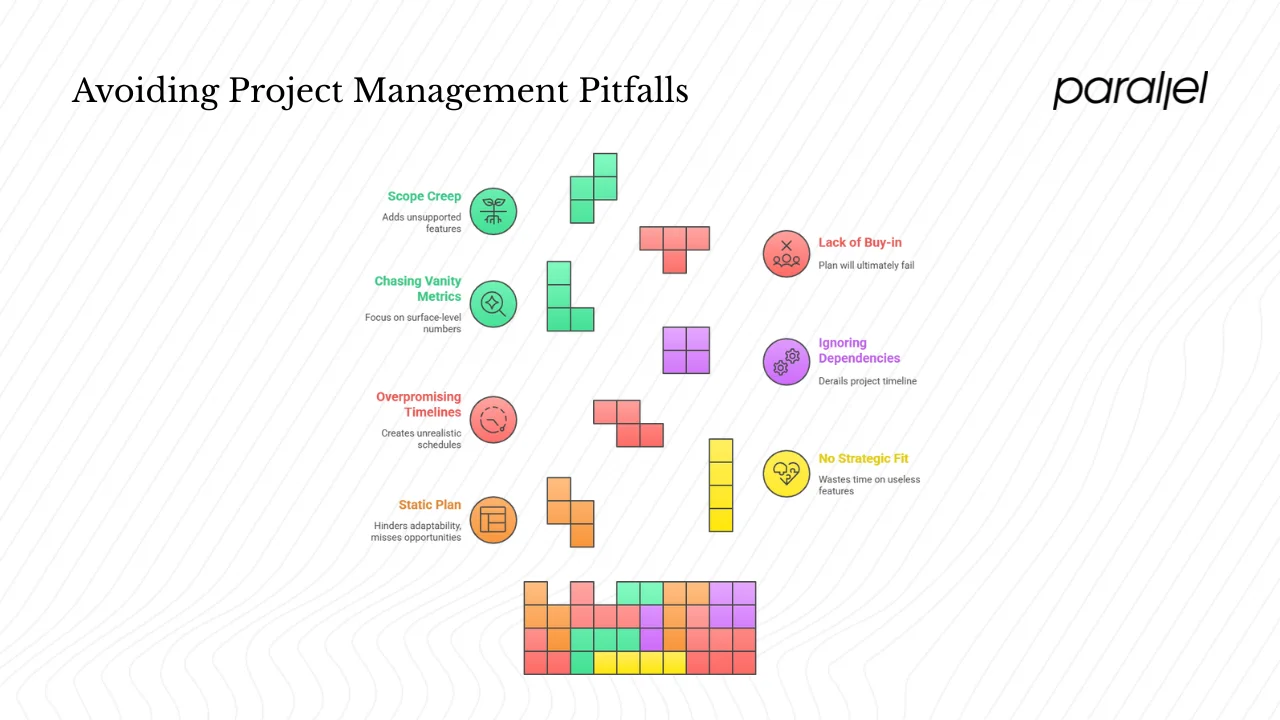

Common mistakes and pitfalls

Even experienced teams make errors. Here are traps to avoid:

- Treating the plan as static. The user story mapping blog warns that rigid adherence to a predetermined plan can hinder adaptability and cause missed opportunities. Be prepared to adjust as new data emerges.

- Building features without strategic fit. Without clear objectives, teams can waste months on features that don’t move the needle.

- Overpromising timelines. Pressure to show progress can lead to unrealistic schedules. Under‑promise and over‑deliver instead.

- Ignoring dependencies and risk. Overlooking compliance or technical dependencies can derail your timeline.

- Chasing vanity metrics. Choose metrics tied to business impact instead of surface‑level numbers.

- Lack of stakeholder buy‑in. If leaders or colleagues don’t support the plan, it will fail. Bring them in early and incorporate their feedback.

- Scope creep. Resist the temptation to add “just one more feature” unless it’s supported by data.

When to use (and when not to use) a product plan

A product plan is most useful when you have enough context to define a direction—typically after discovery research and before development. It’s especially valuable for early‑stage startups, scale‑ups, or new product lines. It helps secure funding, coordinate teams and track progress. When you’re in an extremely lean exploration phase—testing hypotheses with minimal code—focus on a lightweight backlog or hypothesis board instead. In fast‑changing markets, keep the plan lean and revisit it often; avoid locking in detail too far ahead.

Agile teams might worry that planning is a “waterfall.” In reality, they work together. The plan sets direction; agile rituals (sprints, stand‑ups, retrospectives) control execution. Think of the plan as a compass rather than a contract.

How a product plan relates to other artifacts

The plan sits within a family of product documents:

- Product roadmap: A visual timeline of themes and milestones; it’s narrower in scope and often used to communicate plans to stakeholders. MindManager notes that roadmaps map tasks, resources and timelines.

- Product strategy: A higher‑level document that defines market positioning and long‑term vision. Monday Dev explains that strategy sets the “why” and “what,” while product planning defines the “how” and “when”.

- Requirements and user stories: Detailed descriptions of features and workflows for engineers and designers. They flow from the plan and are refined during sprints.

- Go‑to‑market plan: A marketing and sales plan that outlines how the product will be launched and promoted. Monday Dev notes that go‑to‑market planning follows product planning.

- Backlog and sprint plans: Agile artefacts for day‑to‑day development; they implement the roadmap and adjust tasks based on feedback.

Understanding how these pieces work together prevents duplication and ensures each document serves a clear purpose.

Conclusion

Early‑stage founders often ask me, “Why bother writing a product plan? We just need to ship.” My answer is simple: a plan doesn’t slow you down—it keeps you focused. In a world where nine out of ten startups fail and nearly half collapse because they misread market needs, planning is an act of empathy and discipline. It forces you to understand who you’re building for, why it matters, and how you’ll deliver real value.

Treat your plan as a living artefact. Start small, revisit it regularly, and let evidence guide your decisions. As Nielsen Norman Group says, a roadmap (and by extension a plan) is a strategic, living artifact that aligns and communicates future work. The same is true of the product plan. When you approach planning with curiosity and humility, you set your team up not just to build features, but to solve problems that matter.

FAQ

1) What is the meaning of a product plan?

A product plan is a strategic document that captures the direction, features, timeline and metrics for a product. It translates your vision into actionable steps and helps unify everyone around the same objectives. ProductPlan explains that product planning produces a plan outlining strategic themes, feature priorities and timelines, while MindManager clarifies that the plan describes what the product is, who it’s for and why it’s being developed.

2) How do you write a product plan?

Start with discovery research and define your vision and objectives. Identify your target audience and value proposition. Brainstorm features, then prioritise them using frameworks like RICE. Create a timeline with milestones, allocate resources, identify dependencies and risks, set metrics, and embed a feedback loop. Share the plan, gather feedback and iterate. This nine‑step process mirrors the sections above and the principles shared by Monday Dev that planning is an ongoing cycle.

3) What are the 4 P’s of product planning?

In marketing, the “4 P’s” are product, price, place and promotion. In product planning, some practitioners repurpose the acronym to mean purpose (vision and objectives), people (target audience and team), process (steps and timeline), and performance (metrics and outcomes). The exact interpretation varies by framework. The key is ensuring that you cover why you’re building, for whom, how you’ll build and how you’ll measure success.

4) What are the components of a product plan?

A solid plan includes business objectives, target audience and personas, market and competitor analysis, feature prioritisation, timeline and milestones, resource allocation, dependencies and risks, KPIs and metrics, and a feedback loop for iteration. These elements are grounded in research and best practices outlined earlier.

5) Why should early‑stage startups bother with planning?

Because most startups fail, often due to misreading market needs. Planning reduces this risk by forcing you to validate assumptions, focus on evidence, and coordinate your team. It gives investors confidence and makes it easier to adapt when conditions change.

.avif)