What Is Product Portfolio Management? Guide (2026)

Understand product portfolio management, how it balances resources across products, and its impact on strategic decision‑making.

A founder once asked me: “What is product portfolio management and why should I care when my startup has only one product?” My answer is that even the simplest product sits within a broader picture. Managing that picture means choosing where to invest your finite time and money. It means deciding which ideas to pursue, which to postpone and how everything ties back to your mission. In this guide I’ll explain the idea, show why it matters for startups, outline the core components and provide a framework to help you build, optimize and measure your portfolio so you grow deliberately rather than by accident.

What is a product portfolio?

A product portfolio is the collection of all the offerings your company provides. Roman Pichler describes it as a group of related products or variants that share a vision and serve a target group. Think of Microsoft Office: Word, Excel and PowerPoint are different products but belong to one portfolio. In a startup the portfolio might include a core platform, a paid extension and an experimental beta. Seeing them together helps you understand how customers perceive your brand and how investors judge your growth potential.

What is product portfolio management?

When someone asks me again, “So what is a product portfolio management?”, I explain that it’s the discipline of overseeing and optimising that collection of products. Productboard defines it as evaluating and prioritising resource allocation across products to ensure they fit company goals, market needs and profitability. It’s more than building roadmaps; it involves analysing performance, deciding when to develop, maintain or retire offerings and ensuring that each product’s strategy inherits the overarching vision. This perspective is different from product management, which focuses on a single product and its features.

Why it matters for early‑stage startups and design leaders

Early founders often see portfolio thinking as a luxury. Yet starting with this mindset pays dividends. First, it improves resource allocation: by comparing investments across products you can direct team energy and budget to the highest‑value opportunities. Second, it mitigates risk through diversification; a balanced mix of products at different lifecycle stages makes your business more resilient. Third, it ties every decision back to your mission: Pichler stresses that individual product strategies should inherit the overarching portfolio vision.

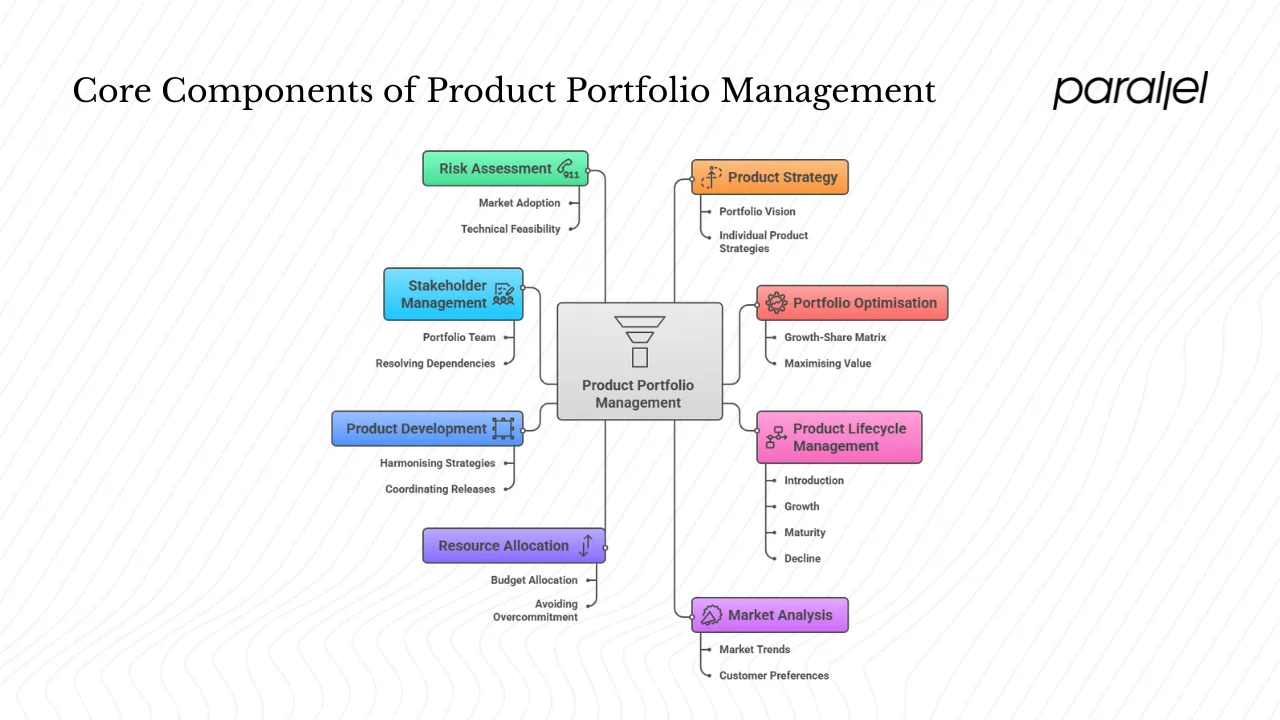

Core components of product portfolio management

1) Product strategy

When thinking about product strategy it helps to revisit what is a product portfolio management. A portfolio strategy sets guardrails for individual product strategies. Pichler’s portfolio vision for Microsoft Office — enabling people to get things done — informs the visions of Word, Excel and PowerPoint. For a startup, writing down your vision and goals at the portfolio scope clarifies which products fit and which don’t.

2) Portfolio optimisation

Optimisation means balancing your mix of offerings. The growth‑share matrix plots products by market share and growth: Stars, Cash Cows, Question Marks and Dogs. Cooper and Edgett list maximising value and achieving balance as core goals of portfolio management. For example, invest in a star product, harvest cash cows to fund innovation, evaluate question marks carefully and consider retiring dogs.

3) Product lifecycle management

Products pass through introduction, growth, maturity and decline. Early stages require heavy marketing and low sales. Growth brings rising demand, maturity yields peak profit and stiff competition, and decline occurs as alternatives appear. Tracking lifecycle stages helps you know when to invest, when to maintain and when to sunset an offering.

4) Market analysis

Market analysis looks at past features. Productboard advises monitoring market trends and customer preferences to keep the portfolio relevant. For startups, this means talking to customers, studying competitors and mapping each product to a segment. Use the insight to avoid overlapping offerings and to identify adjacencies.

5) Resource allocation

Cooper and Edgett define portfolio management as a continual decision process where resources are allocated and re‑allocated to active projects. Set guardrails: decide what percentage of your budget goes to core products, growth bets and experiments. Resist funding every idea and avoid overcommitting.

6) Product development

Portfolio thinking influences development choices. Instead of responding to every feature request, ask whether a new product or feature supports the portfolio vision. Pichler advises harmonising strategies and roadmaps across products and coordinating releases to avoid conflicts.

7) Stakeholder management

Managing a portfolio requires coordination across teams. Pichler suggests building a portfolio team that includes the head of product, product managers, development reps and important stakeholders. This team reviews strategy, resolves dependencies and ensures broad buy‑in.

8) Risk assessment

Risk takes many types: market adoption, technical feasibility and portfolio imbalance. Stage‑Gate’s authors observe that portfolio decisions are made with uncertain and changing information. Mixing stable cash cows with exploratory bets hedges risk. Regularly revisit assumptions and be ready to pivot if signals are weak.

9) Performance metrics

Individual products track metrics like active users. At the portfolio scope you need revenue distribution, growth rates, return on investment, resource utilisation and time to market. Productboard emphasises analysing revenue growth, profitability, market share and customer satisfaction for each product.

10) Business objectives fit

A strong portfolio maps every product to business objectives. Pichler stresses that individual product strategies must inherit the portfolio vision and business goals. Stage‑Gate emphasises strategic fit as a core goal. Before launching a new product, check whether it advances your mission and revenue targets.

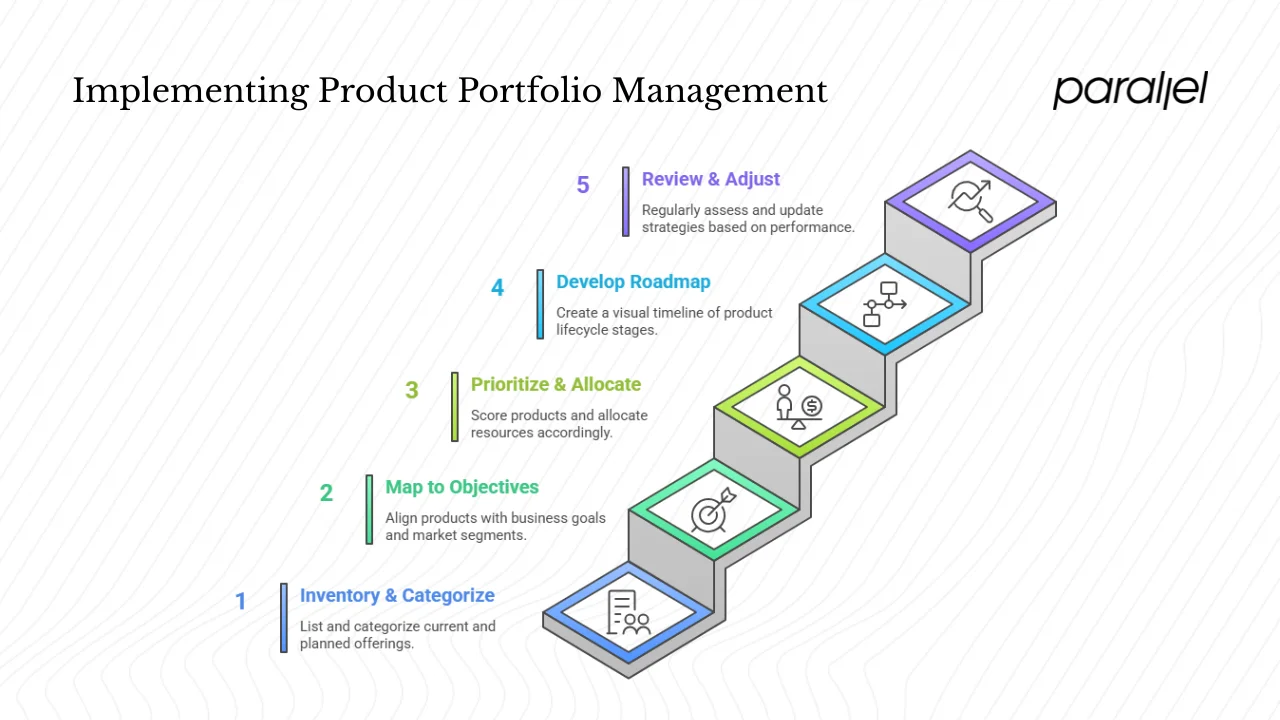

Framework for implementing product portfolio management in a startup

You don’t need expensive tools to start managing a portfolio. This simple framework works well for early teams.

Step 1: Inventory and categorise

Make a list of your current and planned offerings. Categorise them as core, growth or innovation, and record their lifecycle stage. This inventory gives everyone a shared view of the portfolio.

Step 2: Map to objectives and market

Write down how each product supports a business goal and which segment it serves. Productboard suggests matching products with the mission and monitoring market trends. Identify gaps or overlaps; for example, two products may target the same segment but compete for resources.

Step 3: Prioritise and allocate resources

Score products based on value, risk and cost. Cooper and Edgett describe scoring models and risk‑reward diagrams to maximise portfolio value. Rank the initiatives and allocate budget and team capacity accordingly. Be prepared to say no to lower‑value ideas.

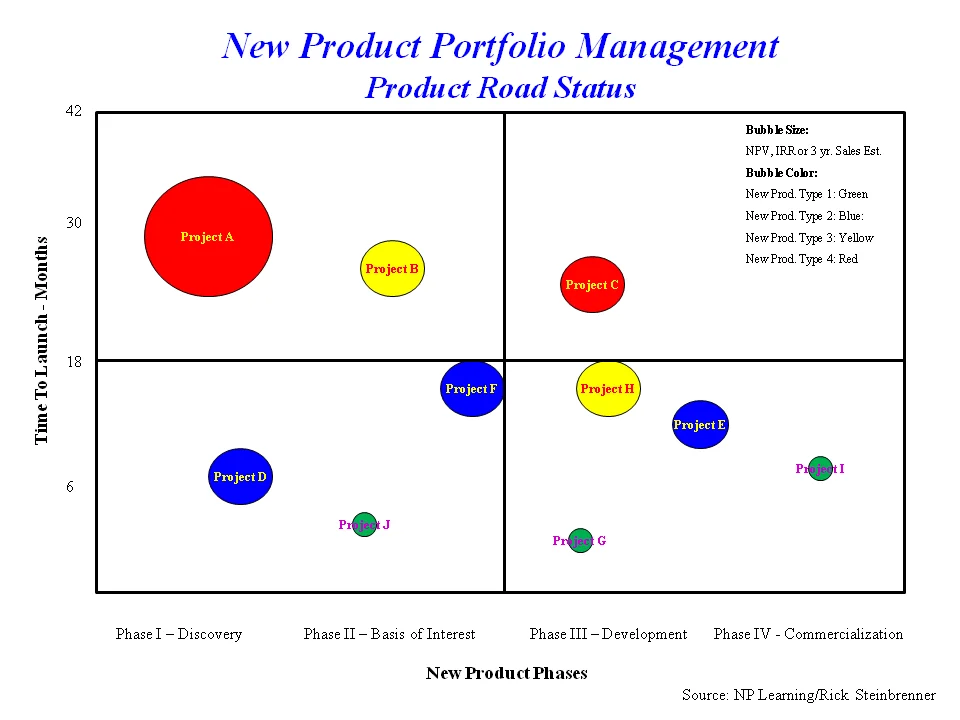

Step 4: Develop a portfolio roadmap

Create one roadmap that shows timing and dependencies across products. Visualise when each product will reach different lifecycle stages and how resources shift over time. This holistic view uncovers conflicts and helps with planning.

Step 5: Review and adjust

Regularly review the portfolio. Pichler suggests a quarterly cadence to consider performance, market changes and new trends. Update your strategies and resource allocation based on what you learn.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Not sunsetting products: Teams often keep underperforming products alive, diluting resources. Use lifecycle data to decide when to retire.

- Confusing portfolio with product strategy: Let the portfolio vision guide individual roadmaps.

- Ignoring stakeholder buy‑in: Decisions made in isolation breed resentment. Pichler advocates a collaborative portfolio team.

- Overcommitting: Stage‑Gate warns against taking on more projects than you can handle.

Startup‑specific considerations

Keep the process simple. Use spreadsheets or whiteboards instead of enterprise software. Review more frequently than large companies and be ready to pivot quickly based on feedback or investor guidance.

Case examples and practical scenarios

Consider a SaaS startup with a core analytics platform, a customer engagement add‑on and a machine‑learning beta. The core platform is a cash cow that funds the business. The engagement adds‑on sits in the growth quadrant, so the team invests in new features. The beta is a question mark; the team limits resources until customer uptake is proven. They allocate 60% of engineering to the core platform, 30% to the add‑on and 10% to the beta, reviewing quarterly and adjusting based on adoption.

A larger example is Microsoft 365. Word, Excel and PowerPoint share a portfolio vision of enabling productivity. Their strategies inherit this vision and target group. When the company emphasises collaboration, each product builds features that support that goal.

Tools and techniques

Several tools support portfolio management:

- Growth‑share matrix: Maps products into stars, cash cows, question marks and dogs for balanced decisions.

- Scoring models: Give importance to value, risk and cost to rank investments.

- Dashboards: Simple spreadsheets showing revenue, growth, lifecycle stage and resource allocation.

- Roadmap templates: Visual timelines that depict dependencies across products.

- Governance models: Regular review meetings with product, design, engineering and business leaders to ensure decisions are transparent.

Revisiting the question

In practice the question of product portfolio management is not something you answer once and forget. It becomes a mantra. Each time we evaluate a new feature or pivot a strategy, we ask ourselves: what is a product portfolio management decision here? When discussing trade‑offs with founders, I often repeat: what is a product portfolio management lens telling us? When mentoring new product leaders, I encourage them to ask: what is a product portfolio management practice in this context? Even after years in this field I still pause to consider: what is a product portfolio management problem I'm solving right now? The repeated question keeps your thinking grounded.

Benefits and ROI of product portfolio management

A disciplined approach delivers real value:

- Resource efficiency: By focusing on high‑potential products, you maximize return on investment.

- Strategic clarity: When roadmaps inherit the portfolio vision, teams work toward a common mission.

- Risk management: Diversifying across lifecycle stages and market segments spreads risk.

- Faster delivery: Fewer, better‑prioritised projects mean shorter time to market.

- Data‑driven decisions: Metrics allow leaders to adjust based on evidence.

Challenges and how to address them

Common challenges include data silos, cultural resistance, limited capacity and lack of process. Create a single source of truth with a shared dashboard; make lifecycle status and performance visible so teams are comfortable retiring products; prioritise ruthlessly so you don’t take on too many projects; and establish a regular review cadence to keep the portfolio on track.

Conclusion

In the end, the question of product portfolio management is about mindset. It encourages founders and design leaders to think in systems rather than silos. By seeing all your offerings together, mapping them to objectives and allocating resources deliberately, you avoid spreading yourself too thin. In my work with machine‑learning and SaaS teams, those who adopt portfolio thinking early make better decisions and communicate more clearly. If you want to grow sustainably, start your portfolio work today. Ask: what is a product portfolio management practice inside my company? Do I know where each product sits in its lifecycle? Are we investing our limited capacity in the right mix of core, growth and exploratory bets? Answering these questions will set you on a path to smarter growth.

FAQ

1. What does product portfolio management mean?

It is the practice of overseeing and optimising the full suite of a company’s offerings. Productboard defines it as evaluating and prioritising resource allocation across products so they fit company goals, market demands and profitability. Pichler adds that it includes analysing the portfolio, updating strategy and adjusting the mix by adding or removing products.

2. What is an example of a product portfolio?

Microsoft 365 is a prime example: Word, Excel and PowerPoint sit under one vision of enabling productivity, and their strategies inherit that vision. In startups, a core product plus an extension and a beta make up a portfolio that should be managed as a whole.

3. How much does a product portfolio manager make?

Compensation varies by region and industry. A salary survey from a product management platform indicates that in 2025 the average base salary for a product portfolio manager in the United States is about $115,000, with top performers earning up to $150,000 and bonuses ranging from 10% to 20%. Salaries tend to be higher in tech and pharmaceutical sectors and lower in retail or hospitality.

4. What are the four dimensions of a product portfolio?

The growth‑share matrix uses two dimensions — market growth and relative market share — to classify products as stars, cash cows, question marks or dogs. Another way to view dimensions is breadth (number of products), depth (variants), risk‑return profile and lifecycle stage. A balanced portfolio considers all these aspects.

.avif)