What Is a Prototype? Guide (2026)

Discover prototypes, interactive models of a product used to test design concepts and functionality.

Most people underestimate how hard it is to launch a successful software product. Recent research suggests that 70%–90% of new products struggle to gain lasting traction, with startups facing 60%–80% failure rates. Those sobering statistics aren’t meant to scare you; they set the stage for why prototypes matter. Prototypes give teams a safe space to test, refine, and align on an idea long before engineers commit time and money to build it.

When founders and product leads ask, what is a prototype, they’re really asking how to reduce uncertainty. A prototype is an early version of a product that lets you try ideas, gather feedback, and make informed decisions. If you begin an initiative without knowing what is a prototype, you risk pouring months of effort into the wrong thing.

In my experience guiding AI‑driven SaaS startups at Parallel, prototyping is the difference between pouring months of effort into the wrong thing and quickly validating whether an idea merits deeper investment.

What is a prototype?

When people ask what a prototype is, they’re often expecting a complex answer. In truth, a prototype is an early sample or model built to test a concept before full‑scale production. It can be anything from a paper sketch to a clickable user interface. The Product School defines it as “an early version of a product used to test ideas, gather feedback, and refine designs before full product development”. Simplilearn echoes that framing, describing prototypes as early samples built to test a concept or process and noting that they allow designers and stakeholders to evaluate ideas and user reactions before significant resources are committed.

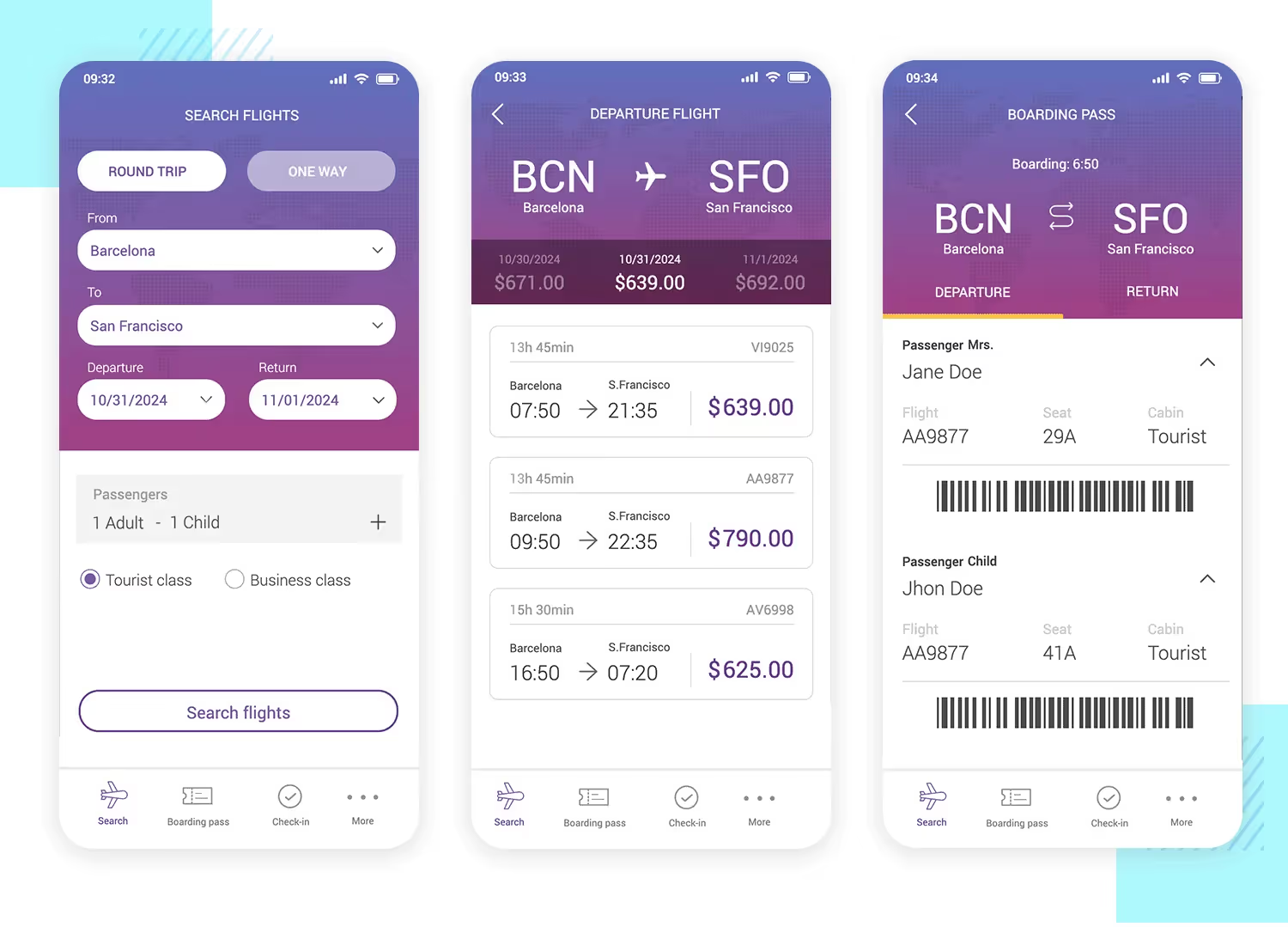

When you’re working on a web or mobile product, a prototype usually takes the form of a clickable version of the interface. TheTin describes interactive prototypes as “designed sets of screens where users can click and navigate around the product”. Tools like Figma or InVision let you import sketches or fully designed screens, connect them with hotspots, and simulate basic interactions. This gives stakeholders and testers a tangible, navigable model of the product without writing production code.

How prototypes differ from other artefacts

It’s common to confuse prototypes with related deliverables, but each serves a distinct purpose:

- Design mockups are static visual compositions. They show how an interface looks but not how it behaves. Prototypes, on the other hand, allow interaction. They enable you to test flows and micro‑interactions, not just aesthetics.

- User interface samples (sometimes called comps) showcase a polished layout or style. Like mockups, they are static images and do not permit user input or navigation.

- Proof of concept (PoC) focuses on technical feasibility. A PoC tests whether a particular technology or architecture can address a problem. Apptension describes a proof of concept as a way “to test the idea’s underlying general assumptions and ensure it can be implemented technically”. It might include a working component built with the intended technology. A prototype, by contrast, concentrates on the user experience, exploring how the product works from the user’s perspective. A PoC can be part of a prototype, but they are not the same thing.

Startups rely on prototypes because they offer a low‑cost way to align teams and validate concepts. When you have a rough version of your product, it’s much easier to gather feedback from potential users, investors, and colleagues. Christina Goldschmidt, VP of Product Design at Warner Music Group, explains that showing a sketch or prototype allows everyone to understand the idea quickly and have meaningful discussions. Without a prototype, product requirements are often abstract and misinterpreted, leading to misalignment and rework.

Why prototyping matters in product development

Once you have a grasp of what is a prototype, the next question is why creating one matters during development. Understanding this lays the groundwork for effective product planning.

1) Reducing risk and saving resources

Building software is expensive, and mistakes compound as you move closer to launch. Prototyping helps teams reduce development risks by catching problems early. Product School lists reducing development risk, improving user experience, speeding decision‑making, and saving time and money among the benefits of prototypes. Simplilearn further notes that prototypes let you identify technical, financial, or design constraints and adjust before committing resources. In practical terms, a $5 sketch that surfaces a faulty assumption saves the tens of thousands you would otherwise spend building a feature no one needs.

2) Aligning designers, PMs, engineers and stakeholders

One of the hardest parts of product work is ensuring everyone interprets requirements the same way. Prototypes serve as a shared reference point. They turn bullet‑point requirements into something you can see and interact with. Product School highlights that prototypes ensure team alignment and boost stakeholder confidence. From my own experience, giving engineers a prototype early prevents misinterpretations that would otherwise emerge during code reviews. Designers and PMs can discuss flows using the same artefact. Investors can see progress and provide input that might alter the roadmap.

3) Encouraging feedback and iteration

When feedback arrives late, making changes is painful. A prototype invites feedback when it’s still cheap to adjust. TheTin notes that interactive prototypes help stakeholders and users gain a visual understanding of a webpage or app at an early stage, which makes it easier to make corrections. Early feedback also drives empathy; Simplilearn remarks that prototyping “generates empathy for prospective consumers” and helps identify unnecessary features. At Parallel, we use quick low‑fidelity prototypes in user interviews to uncover pain points before our engineers write a single line of production code.

4) Supporting pitches and funding conversations

Many founders need to secure investment before they can build a full product. Prototypes are powerful in investor or client meetings because they show rather than tell. A tangible model conveys the value proposition better than a slide deck. Product School mentions that prototypes help secure funding or buy‑in. When potential investors can click through a concept, they understand the vision and are more likely to invest.

5) Avoiding costly coding mistakes

Coding an idea only to discover that users don’t understand it is demoralizing. Prototyping allows teams to test interactions and refine flows before committing to code. Simplilearn points out that prototypes allow you to “discover design errors and check their correctness before going into production”. In my work, I’ve seen teams scrap months of engineering work because the concept didn’t resonate with users. Prototypes would have uncovered those issues in days.

Types of prototypes

Not all prototypes are equal. Different stages of the product lifecycle call for different levels of fidelity. Knowing what is a prototype will help you choose the right level of detail at the right time. Here are the main types you’re likely to use.

Low‑fidelity prototypes

Low‑fidelity prototypes are simple and inexpensive. They include paper sketches, whiteboard wireframes, or digital wireframes with minimal styling. TheTin lists paper (sketches) and wireframes among the main prototype categoriesthetin.net. These rough representations help teams explore ideas quickly and iterate without getting bogged down in details. Use low‑fidelity prototypes during the brainstorming phase or when you need to agree on user flows and screen hierarchy. Their informal nature encourages stakeholders to suggest changes without worrying about aesthetics.

High‑fidelity prototypes

High‑fidelity prototypes closely resemble the final product in look and interaction. They include interactive UI samples built from polished designs. Product School notes that high‑fidelity prototypes “simulate the final product more closely”. They are typically created once core flows are validated and you need to test usability, transitions, and micro‑interactions. High‑fidelity prototypes are useful for stakeholder demos and user testing sessions where realistic behaviour matters. However, they take longer to build; if you invest too much time in polishing them too early, you risk delaying feedback.

Proof of concept

A proof of concept (PoC) is not exactly a prototype but is often mentioned in the same breath. As Apptension explains, its primary purpose is to validate technical feasibility by testing a technology or approach. A PoC might involve building a small component or service to verify that an algorithm can handle real‑world data, or that a third‑party API works at scale. It does not focus on user flows or interface, but on verifying that the idea can be built. In some cases, teams create a PoC first, then follow with a prototype to evaluate the user experience.

Design mockups versus prototypes

Design mockups are static, polished visuals used to convey the aesthetic direction of a product. They show color, typography, spacing, and brand elements, but they don’t let you interact with the product. A prototype adds interaction and flow to the equation. You might start with mockups to agree on visual direction and then link those screens together to produce a high‑fidelity prototype for testing.

The prototyping process

Prototyping isn’t a single event; it’s a process that encourages iteration and learning. Once you understand what is a prototype, you can follow a repeatable approach that keeps teams focused and lean. In our work with early‑stage startups at Parallel, we follow a process that keeps teams focused and lean:

- Define the problem and goal: Before drawing anything, clarify the user problem and what you need to learn. Without a clear question, a prototype can devolve into guesswork.

- Sketch or wireframe ideas: Start with quick sketches or low‑fidelity wireframes. These help you map user flows, decide on screen hierarchy, and get internal alignment.

- Build a low‑fidelity prototype: Use tools like Figma, InVision, or Adobe XD to connect your sketches or wireframes into a clickable model. TheTin notes that interactive prototypes allow you to test changes to user flow efficiently.

- Test internally and refine: Share the prototype with your team. Walk through different scenarios. Listen for confusion or friction. Adjust the flow and layout before showing it to users.

- Create a high‑fidelity prototype for usability testing: Once the concept is solid, apply visual styling and add realistic interactions. Product School emphasizes that high‑fidelity prototypes are better suited for usability testing and stakeholder demos.

- Gather stakeholder and user feedback: Show the prototype to potential users, investors, and partners. Ask open‑ended questions to uncover surprises. The goal is to learn, not to impress.

- Iterate until ready for development: Incorporate feedback, refine the prototype, and repeat the testing cycle. As the prototype stabilizes, involve engineers to confirm feasibility and plan the build. Only after this cycle should you commit to development.

Tools to consider

Modern tools make prototyping accessible to everyone, not just designers. Figma has become the default choice for collaborative design and prototyping. InVision offers interactive linking and user testing capabilities. Adobe XD provides an integrated environment for design and prototyping. TheTin article notes that interactive prototypes are often built using Figma or InVision. Choose the tool that fits your team’s workflow and skillset rather than chasing the latest trend.

Best practices for effective prototyping

Prototyping is both an art and a discipline. These guidelines help teams get the most out of their efforts:

- Start simple and move fast. Begin with sketches or wireframes. You’ll learn more by testing a simple flow today than by polishing a complex design for weeks.

- Test early and often. Show your prototypes to users, colleagues, and stakeholders throughout the process. Frequent feedback prevents wasted effort and surfaces blind spots.

- Balance fidelity with speed. Use low‑fidelity prototypes to explore ideas quickly. Shift to high‑fidelity when you’re confident in the flow and need to test nuance, such as micro‑interactions or visual hierarchy.

- Adapt to your audience. Stakeholders and investors might care about narrative and vision, whereas users care about whether they can accomplish tasks. Tailor the fidelity and scope of your prototype to who will be reviewing it.

- Avoid the pixel‑perfect trap. It’s tempting to obsess over every pixel, but early prototypes should prioritize learning. Leave room for change. Perfection too early can create resistance to feedback and slow you down.

From my experience at Parallel, the most successful prototypes were the ones we built quickly and were willing to discard. When teams invest too much emotionally in a prototype, they become reluctant to make necessary changes. The prototype is a learning tool, not the final deliverable.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

Even experienced teams fall into common traps when prototyping. Here are some mistakes to watch for and how to sidestep them:

- Mistaking the prototype for the final product: A prototype is meant to test ideas. Don’t treat it as the finished design. Keep communication clear that the prototype is subject to change.

- Overinvesting in polish too early: Spending days perfecting color schemes or animations on an unvalidated idea wastes time. Focus on the core flow first. Polish once the concept has traction.

- Ignoring user feedback: It’s easy to dismiss negative feedback because it contradicts your vision. But the whole point of prototyping is to learn. Listen carefully, ask follow‑up questions, and adjust.

- Excluding engineers from the process: Engineers provide valuable perspective on feasibility and constraints. Involve them early so that your prototype is grounded in reality and future handoff is smoother.

Conclusion

Prototypes are more than pretty models; they’re essential tools for reducing risk, aligning teams, and building products that people actually need. In a world where 70%–90% of new products fail and startups face particularly high failure rates, prototyping offers a pragmatic way to de‑risk your vision. By starting with low‑fidelity sketches, testing early, and iterating through higher‑fidelity versions, you can uncover insights that save time and money.

If you started this piece wondering what a prototype is, you now know it’s a tool for learning and validation, not just a deliverable. Whether you’re pitching investors, guiding a small team, or leading a design organization, prototypes will help you turn ideas into tangible products with confidence. Build them early. Test them often. Treat them as learning tools, and you’ll make better decisions.

FAQs

1) What is a prototype in simple words?

A prototype is an early version of a product used to test and refine ideas before investing in full development. It helps teams validate assumptions and learn from user feedback.

2) What is an example of a prototype?

A low‑fidelity example could be a hand‑drawn paper sketch showing the layout of a mobile app. A high‑fidelity example might be a clickable Figma file that lets users tap through screens and experience the flow of the product.

3) Why do we use a prototype?

Prototypes reduce the risk of building the wrong thing. They clarify requirements, align stakeholders, and expose problems early. Research shows that prototypes reduce development risks, improve user experience, speed decision‑making, and save time and money.

4) What is a prototype product?

A prototype product is a preliminary version of a product used to evaluate feasibility and user experience. Unlike a proof of concept—which tests whether a technology works—a prototype focuses on how users interact with the product and helps refine its design.

.avif)