What Is Tree Testing? Guide (2026)

Discover tree testing, a usability method for evaluating navigation structures and improving information architecture.

Why do some websites feel effortless while others bury key pages? After watching dozens of early‑stage products we kept coming back to one question: what is tree testing, and how can it help? Tree testing is a user‑experience research method where participants navigate a plain‑text menu to locate information.

By stripping away visual design, it isolates your information architecture and reveals whether labels and grouping align with users’ mental models. In this guide we explain why navigation structure matters and provide a practical roadmap for founders, product managers and design leaders.

What is tree testing?

A tree test answers a straightforward question: can users find what they need in your navigation tree? Participants start at the “root” of the menu and click through branches until they select the leaf node where they expect to find information. There is no search box and no visual styling; only labels and indentation. The Decision Lab defines tree testing as a method for evaluating how easily users locate key resources within a website or app by focusing on the navigation tree. MeasuringU echoes this, describing the technique as a way to quantify findability by using only labels and structure.

Tree testing lives within usability testing but has a narrower scope. Traditional usability tests observe users interacting with prototypes or live sites, revealing flow issues and interface problems. Tree testing strips away those layers to isolate the information architecture. It is sometimes called “reverse card sorting” because instead of asking users to group content into categories, you ask them to navigate a pre‑built hierarchy. Without design distractions, the test exposes whether labels and grouping logic align with mental models.

The name “tree” is more than a metaphor. In a well‑structured site, the homepage acts as the trunk, main categories form branches and individual pages are leaves. Breadth refers to the number of branches at each level; depth refers to how many levels users must traverse. Too much breadth overwhelms; too much depth buries information. Tree testing helps teams strike a balance by revealing which paths users attempt and where they get lost. Knowing what tree testing equips you to evaluate information architecture early and make adjustments before design work begins. Poor navigation doesn’t just frustrate people—it drives them away. A 2024 Qualtrics report on tree testing notes that 89% of users will leave a site if they encounter a poor user experience, highlighting the business impact of findability failures.

Core concepts & terminology

Before diving deeper into what tree testing is, it helps to know a few terms. The table below summarizes concepts relevant to this method.

How to run a tree test

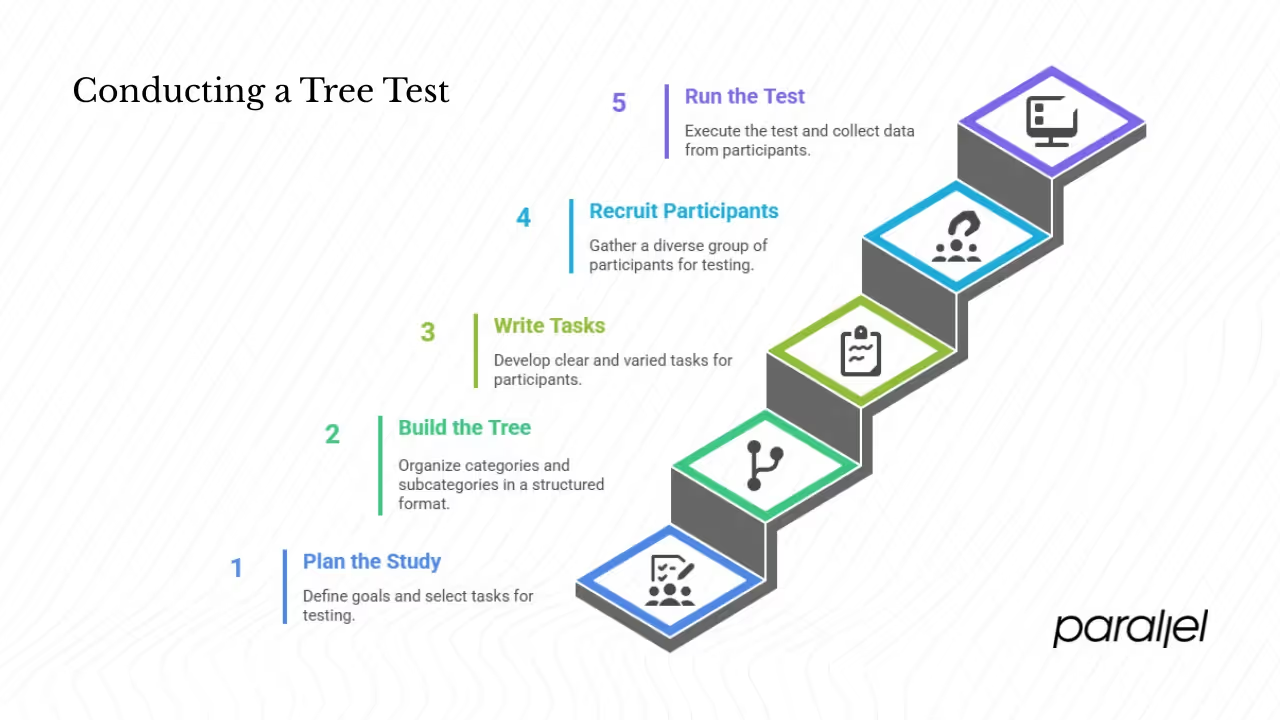

The mechanics of tree testing are straightforward. Here is a condensed roadmap drawn from our experience running tests with early‑stage teams.

1) Plan the study

Start by defining a clear goal (for example, “Can users find pricing?”), then pick a handful of representative tasks that matter most. Decide how much of the tree to test—often just the top two or three levels—and use a tool like Treejack, UXtweak or a simple spreadsheet to build and deploy the test.

2) Build the tree

Compile a list of categories, subcategories and leaf pages, then represent their parent–child relationships in a structured format (CSV or JSON). Use the same labels you plan to use in the product and weed out ambiguous or overlapping terms.

3) Write tasks

Write five to ten tasks in natural language (“You need a refund for your last purchase”) and include a mix of easy, typical and edge‑case scenarios to surface hidden problems without fatiguing participants.

4) Recruit participants

Recruit participants who match your target personas, aiming for a handful for qualitative pilots and 50–150 for quantitative validation. Unmoderated tests scale easily, while moderated sessions let you probe the “why” behind participant choices.

5) Run the test and collect data

Running a tree testing study doesn’t need to be complicated. Provide clear instructions and present tasks one at a time in a text‑only menu. While participants move through the hierarchy, record whether they reach the correct item, whether they backtrack, how long they spend and which top‑level branch they choose first. After each task, invite a brief comment on what confused them so you capture qualitative insights alongside the numbers.

Making sense of the results

1) Interpreting metrics

The numbers from a tree test tell a story. Look at the success rate to see how many participants end up in the right place and at directness to see whether they got there without backtracking. Time on task signals how hard they had to think, while first clicks reveal which high‑level category drew them in. Viewing the full path shows where people detoured or pogo‑sticked.

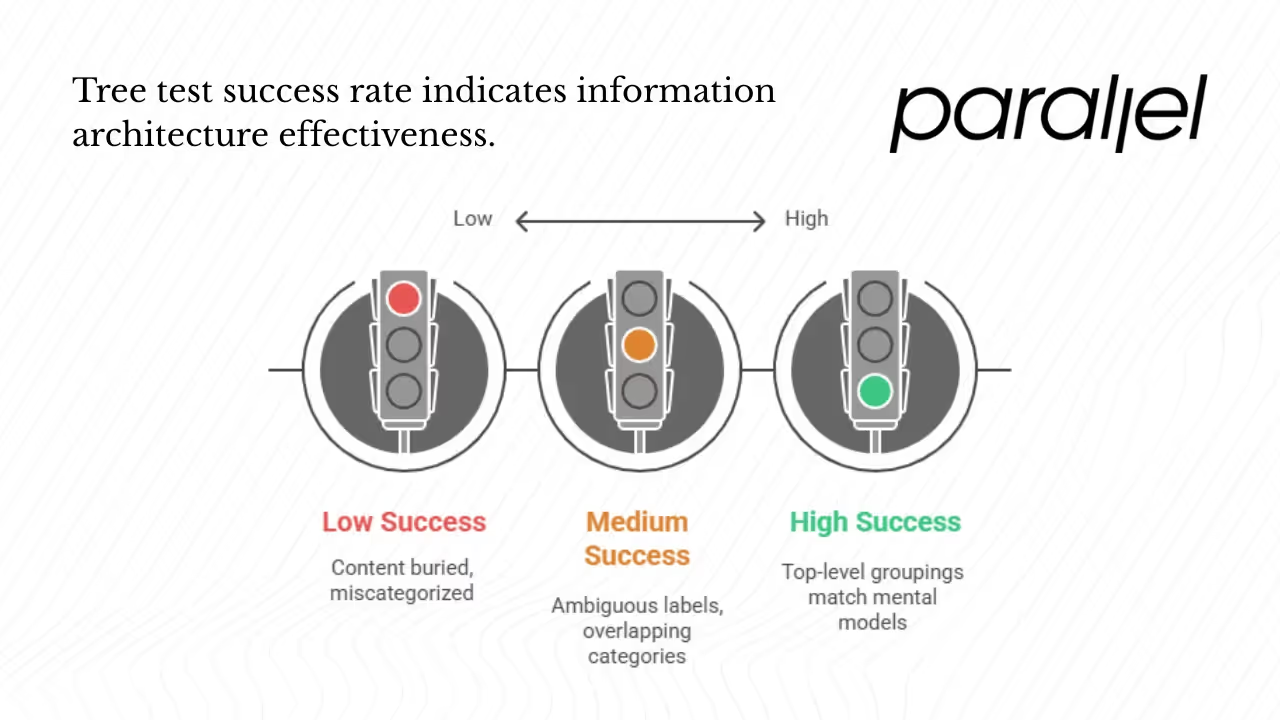

2) What is a good success rate?

There is no universal standard, but many teams treat around 80% as a goal. The University of Arkansas website redesign set an 80% success rate target for each task and treated anything below that as a cue to improve. Simpler products should achieve higher success; complex enterprise systems might accept slightly lower rates. More important than the absolute number is comparing structures and tracking improvement over time.

3) Diagnosing and fixing issues

Patterns in the data point to specific problems: low success combined with long times suggests content is buried or miscategorized; lots of backtracking indicates labels are ambiguous or overlap; scattered first clicks reveal that top‑level groupings don’t match mental models; and rarely used deep branches may be unnecessary. Rename ambiguous terms, reorganize categories, flatten the hierarchy and consider cross‑links where needed. If you’re comparing multiple trees, test each structure with separate participants and pick the one with better metrics and consistency.

Benefits, limitations & best practices

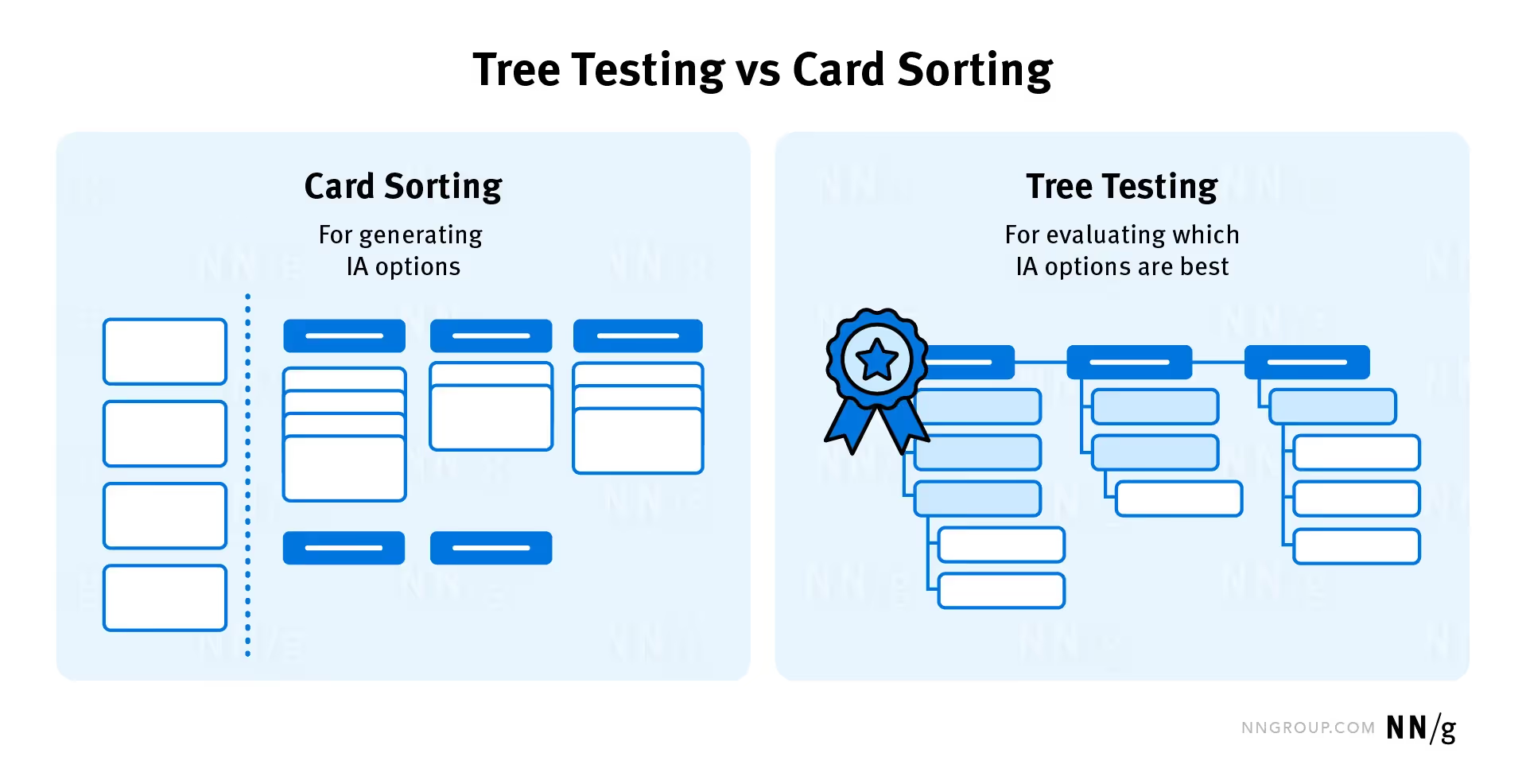

Tree testing vs. card sorting and other methods

Card sorting and what is tree testing often go hand‑in‑hand but serve distinct roles. Card sorting helps you discover how users group information and what labels they use; it is exploratory and generative. Tree testing verifies whether a proposed structure works by measuring findability. Once designs exist, click testing and full usability tests check whether buttons, layout and flow support navigation. Use the right method at the right stage.

Examples and lessons

Successful teams learn by doing. For example, when the University of Arkansas at Little Rock redesigned its website, they iterated through several tree tests—simplifying a complex mega menu until task success climbed above their 80% goal. In another case, a B2B client’s pricing page was buried under “Resources”; moving it to a top‑level “Plans & Pricing” category increased findability from 40 % to 85 % and halved time on task. These stories illustrate patterns we see everywhere: plain language beats jargon, shallow structures are easier to navigate and iterative testing drives improvement.

Advanced variations

Once you’ve mastered the basics, there are many ways to extend tree testing. You can compare multiple candidate trees by assigning different groups to each one, test cross‑listing items in more than one category, hide deeper levels until needed (progressive disclosure), or run localized tests for other languages. Combining the tree with think‑aloud sessions or interviews adds richness. These variations help you tackle complex products and diverse audiences.

Conclusion

So what is tree testing in practical terms? It is a low‑cost, data‑driven method that isolates your navigation structure from visual design to reveal whether users can find what they need. By focusing on labels and hierarchy, tree testing exposes weaknesses in your information architecture and provides clear metrics to guide improvement. Our experience shows that early and iterative tree tests help teams avoid costly redesigns and deliver better user experiences.

If you’re a founder, product manager or design leader, add what is tree testing to your toolbox. Start with a small pilot on your current navigation, observe where participants get lost and which labels mislead them, then rename, reorganize and flatten your tree. After you re‑test, you’ll be surprised how much clarity emerges from this simple, text‑based exercise. Ultimately, answering what is tree testing and applying the method will help ensure users can find content quickly, reducing frustration and boosting satisfaction.

FAQ

1) What does a tree test do?

A tree test evaluates whether users can find specific content using your proposed menu structure. Participants navigate a text‑based hierarchy and select where they expect information to live. The test measures success rate, directness, time and click paths..

2) What is the success rate benchmark in tree testing?

There is no universal rule, but many teams aim for an 80% success rate or higher. The University of Arkansas team used 80% as a goal and treated tasks below that threshold as areas for improvement.

3) How many tasks should a tree test include?

Five to ten tasks are typical. Shorter tests reduce fatigue and maintain data quality. Use fewer tasks in pilot tests and up to ten for larger quantitative studies.

4) Is tree testing similar to card sorting?

They are complementary but distinct. Card sorting helps you discover how users categorize content; tree testing validates whether a proposed structure works by measuring how easily participants find items. A common workflow is to conduct card sorting first and then run a tree test.

.avif)