What Is a User Scenario? Guide (2026)

Understand user scenarios, fictional narratives that describe user goals, and how they guide design decisions.

Earlier this year one of our clients asked for a way to help commuters find cabs during evening rain. The team’s instinct was to push a new booking feature without speaking to users. When we sat with a few commuters the story was very different: some were standing under balconies with spotty networks, others were worried about surge pricing, and a few had credits left in their wallets.

That simple activity made us ask what is the user scenario as a design tool. Far too often teams jump straight into features without pausing to understand how people behave in context. A user scenario is a narrative tool that brings back the human element and keeps product decisions grounded.

In this guide I will explain what it means, why it is useful, how to write one, and how to bring it into your workflow. If you run an early‑stage company or lead design, this will help you make choices with clarity.

What exactly is a user scenario?

The phrase what is the user scenario might seem abstract at first glance. Research communities such as the Interaction Design Foundation define a user scenario as a detailed description of a user in a realistic situation. It goes further than a bullet list of needs; it paints a rich picture that captures motivations, triggers and actions. Because these stories are evocative rather than prescriptive, they help teams understand why someone interacts with a system. I like to think of them as short stories that bring life to the personas we create during research.

A strong scenario usually includes the following components:

- Persona and context: a specific archetype and background, not a generic “user”.

- Situation or environment: where and when the activity takes place, including physical, social and organisational context.

- Trigger or motivation: what prompts the person to act.

- Goal or task: what they want to accomplish.

- Interaction flow: the sequence of steps and decisions they make.

- Constraints and friction: what stands in their way (network issues, budget, time, social pressure).

- Success criteria and failure states: how we know the scenario ends well or poorly.

According to Justinmind’s 2024 write‑up, user scenarios help design teams move beyond goals and into the details of how someone would accomplish a task. They capture the user’s path from start to finish and validate aspects of the design we might overlook. In my own work, scenarios act as a bridge between research and wireframes: they are descriptive enough to inspire empathy yet not so prescriptive that they constrain creativity.

Why use user scenarios

There are good reasons to build scenarios into your process:

- Connecting personas and features – Personas tell us who users are; scenarios show us what they do. The Interaction Design Foundation points out that scenarios promote empathy by providing back stories that explain users’ needs. When you ground a feature in a scenario, you ensure it solves a real problem.

- Context matters – A scenario forces you to think about network speed, environment, social factors and constraints. This often surfaces hidden needs or edge cases. For example, our ride‑booking client realised that commuters without cash needed an alternate payment method during storms.

- Better team alignment – Narratives are easier to discuss than abstract requirements. When the team reads a scenario, everyone pictures the same situation. This improves dialogue between design, product and engineering.

- Testing becomes meaningful – During usability studies, task scenarios engage participants and mirror real use. The details help you write test scripts that uncover friction.

- Driving business outcomes – Strong experiences convert better. A 2025 industry report notes that a well‑designed interface can increase conversion rates by up to 200%, and improved user experience can boost conversions by up to 400%. Companies that invest in user‑centred design see 1.5× faster revenue growth and may yield a return of $100 for every dollar invested. Scenarios help teams design those experiences.

- Spotting risks – By mapping steps and decision points, you can see where users might drop off. The same report points out that 88% of users leave if a page loads too slowly and 61% exit due to unclear navigation. Scenarios help you design around those risks.

My experience working with early stage software teams echoes these points. When a founder shows me a lengthy feature list, my first question is “what scenario are you solving for?” This re‑focuses the conversation from output to outcome.

User scenario vs related concepts

To place scenarios in context, it helps to compare them with other artefacts. The table below summarises how scenarios differ from related tools. Note that the banned word “journey” is replaced with “path map” to describe high‑level sequences.

| Concept | Definition / focus | Relation to user scenario | When useful |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path map (often called user path) | A high-level map of stages a person goes through (e.g., awareness → onboarding → retention). | Scenarios are granular snapshots of a moment within a larger path. | Use path maps for strategic planning, scenarios for detailed cases. |

| User story | A brief statement formatted as “As a ___ I want ___ so that ___”. | Stories capture the what; scenarios provide context and the how and why. | Use stories in agile backlogs; scenarios during design thinking. |

| Use case | A structured specification of interactions between an actor and a system, including steps and exceptions. | Use cases are formal and system-centric; scenarios are narrative and user-centric. | Use when you need to define system behaviour rigorously. |

| Workflow or interaction flow | The path a person takes through an interface. | Scenarios help define and validate flows by asking “in this context, what does the user do next?” | Use flows in wireframes; use scenarios to ground them. |

| Behaviour pattern or user need | Recurring tendencies or needs of users (e.g., scanning, browsing, switching tasks). | Scenarios incorporate these patterns to predict behaviour under constraints. | Use patterns during personal research; feed them into scenarios. |

The purpose of this table is not to claim that one artefact is superior. Rather, each serves a different purpose. In agile teams, user stories may guide backlog prioritisation, while scenarios inform design and testing.

When to use a user scenario in your process

Scenarios are versatile. Here are situations where they add value:

- Early ideation – Before sketching wireframes, write scenarios to test whether an idea solves a real problem. This helps you discard features that sound exciting but don’t meet an actual need.

- After research – Once you have personas and behavioural insights, craft scenarios to bring them to life.

- Before designing flows – Use scenarios to set context and edge conditions. Ask, “In this situation, what will happen?”

- Exploring alternatives – Write multiple scenarios for the same goal to see how different personas might approach it. This reveals trade‑offs.

- Usability testing – Scenario‑based tasks encourage participants to behave naturally. They provide richer feedback than generic instructions.

- Onboarding new team members – Scenarios act as teaching tools. A new engineer can read a scenario and instantly understand why a feature exists.

- Risk spotting – Map out decision points to see where users might drop off. The 2025 stats about user attrition show how slow load times and poor navigation drive abandonment.

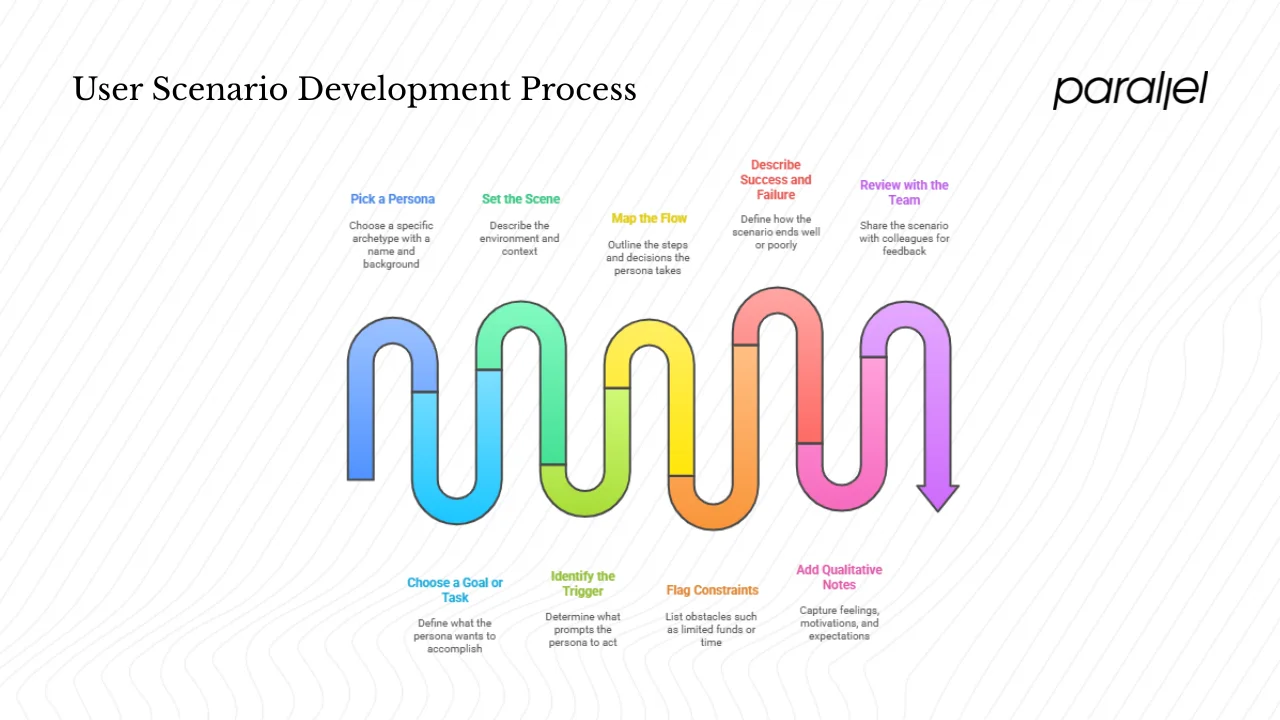

How to write a strong user scenario — step by step

Writing a compelling scenario requires structure and empathy. Here’s a process I use:

- Pick a persona: choose a specific archetype created from research; give them a name and background.

- Choose a goal or task: what does this person want to accomplish? Keep it focused.

- Set the scene: describe the environment, including physical, social and organisational factors. Think about network conditions, mood, time of day.

- Identify the trigger: what prompts the person to act? It might be an event, a need or an emotion.

- Map the flow: outline the steps they take, decisions they make, and alternatives they consider. This can include branching paths.

- Flag constraints: list obstacles such as limited funds, time pressure, technical friction or social concerns.

- Describe success and failure: how does the scenario end well? What would constitute failure?

- Add qualitative notes: capture feelings, motivations and expectations. What is going through their mind?

- Review with the team: share the scenario with colleagues and refine based on feedback.

Tips and guidelines

- Keep it concise but vivid: a paragraph or two is often enough; focus on what matters.

- Use the language your users would use; avoid technical jargon.

- Focus on actions and motivations, not interface details. Don’t specify button colours or layout.

- Use constraints to create tension; trade‑offs lead to insights.

- Validate with real users: show them your scenario and ask if it feels plausible.

I often use a simple template: Persona, Context, Trigger, Goal, Steps, Outcome, Feelings. It’s flexible enough to adapt to different projects.

Real examples

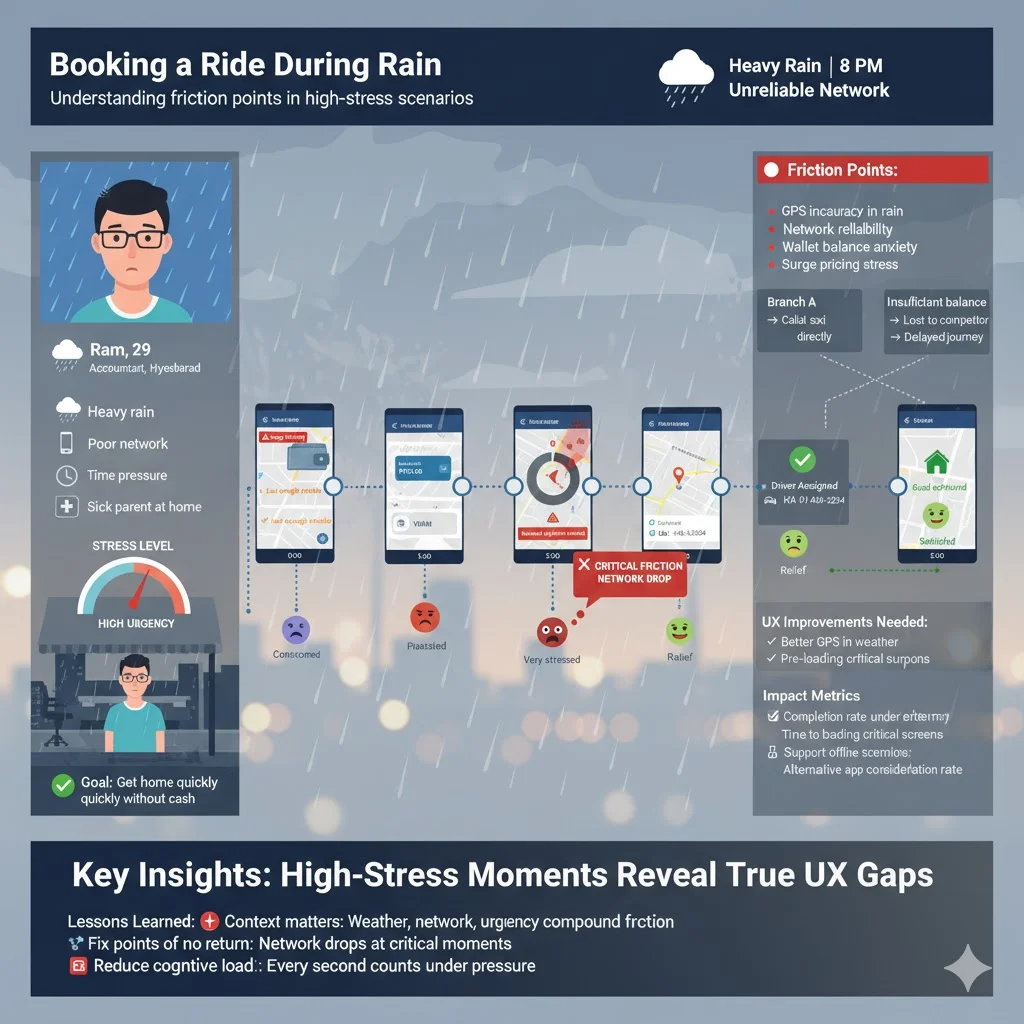

Example 1: Booking a ride during rain

- Persona: Ram, a 29‑year‑old accountant living in Hyderabad.

- Context: It’s 8 pm during a heavy shower. Ram is under a narrow balcony outside his office, his phone network is unreliable and his wallet balance is low.

- Trigger: He needs to get home quickly because he has a sick parent waiting.

- Goal: Book a cab using the company’s ride‑hailing app without using cash.

- Steps:

- Opens the app and sees surge pricing.

- Checks wallet balance; sees he has just enough credits.

- Choose the “wallet” payment method.

- Confirms pickup location using GPS (which is inaccurate due to weather), manually adjusts it.

- Waits for confirmation; network drops and the app shows a loading spinner.

- Considers switching to a competitor app but decides to wait.

- Gets a driver assigned after a minute; receives car details.

- Opens the app and sees surge pricing.

- Branches:

- If the network fails and the app times out, he might call a taxi directly.

- If the wallet balance is insufficient, he might try to borrow cash from a colleague.

- If the network fails and the app times out, he might call a taxi directly.

- Outcome: He books successfully and reaches home. The scenario revealed the need to improve GPS accuracy during weather events and to support offline confirmation.

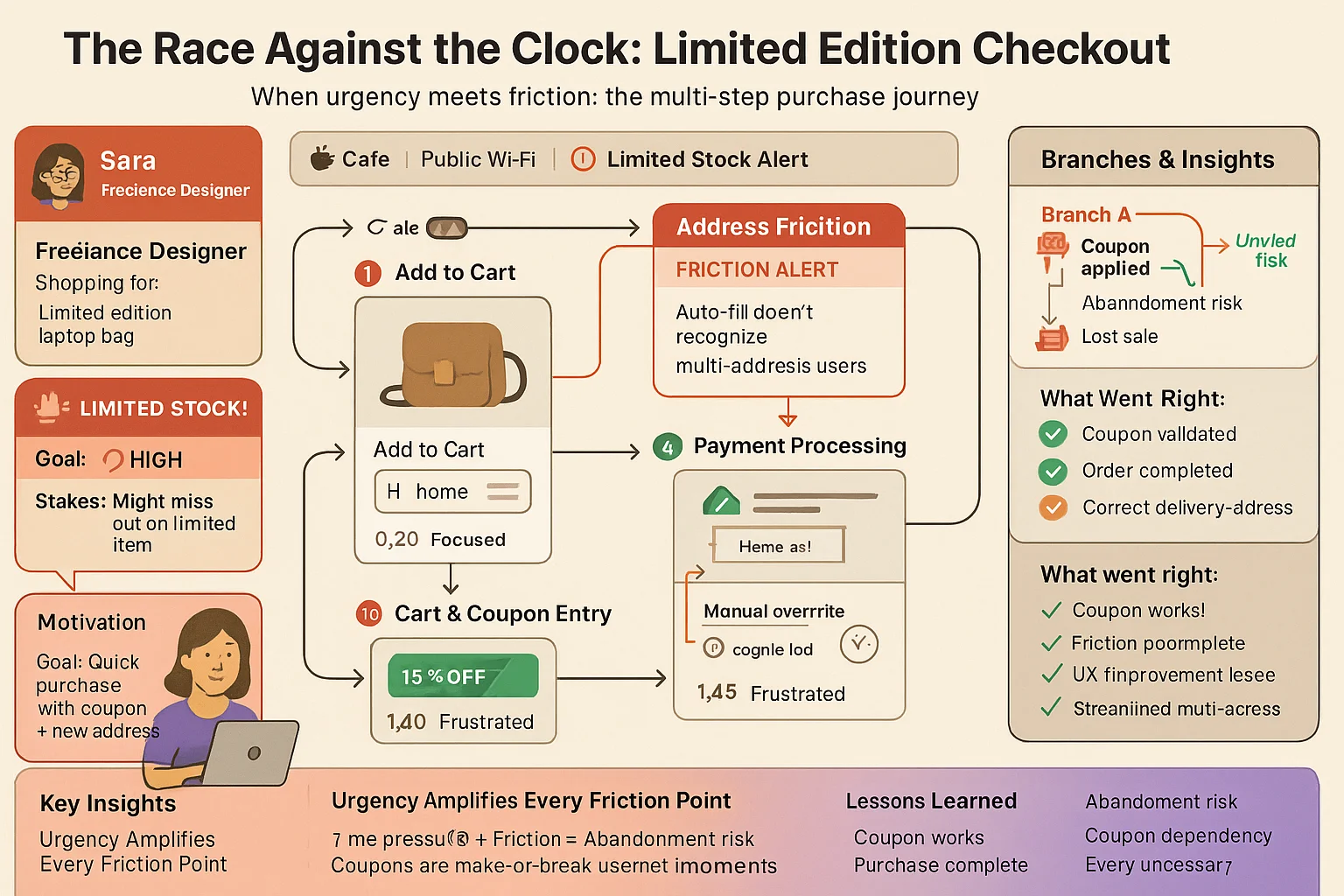

Example 2: Checkout with coupon and address change

- Persona: Sara, a freelance designer, shopping for a limited‑edition laptop bag.

- Context: She’s at a café on public Wi‑Fi. She has a coupon code from an email and wants the bag delivered to her coworking space.

- Trigger: A promotional pop‑up about the limited stock.

- Goal: Complete the purchase quickly using the coupon and update the shipping address.

- Steps:

- Add the bag to the cart.

- Open the cart and enter the coupon code.

- Edits her default shipping address to the coworking space.

- The form auto‑fills with her home address; she has to overwrite it.

- Proceeds to payment; the coupon reduces the price.

- Confirms the order.

- Add the bag to the cart.

- Branches:

- If the coupon is invalid, she might abandon the purchase.

- If the address form does not save the new location, she might contact support.

- If the coupon is invalid, she might abandon the purchase.

- Outcome: She completes the purchase. The scenario highlights the friction of auto‑fill on multi‑address accounts and the risk of coupon codes failing.

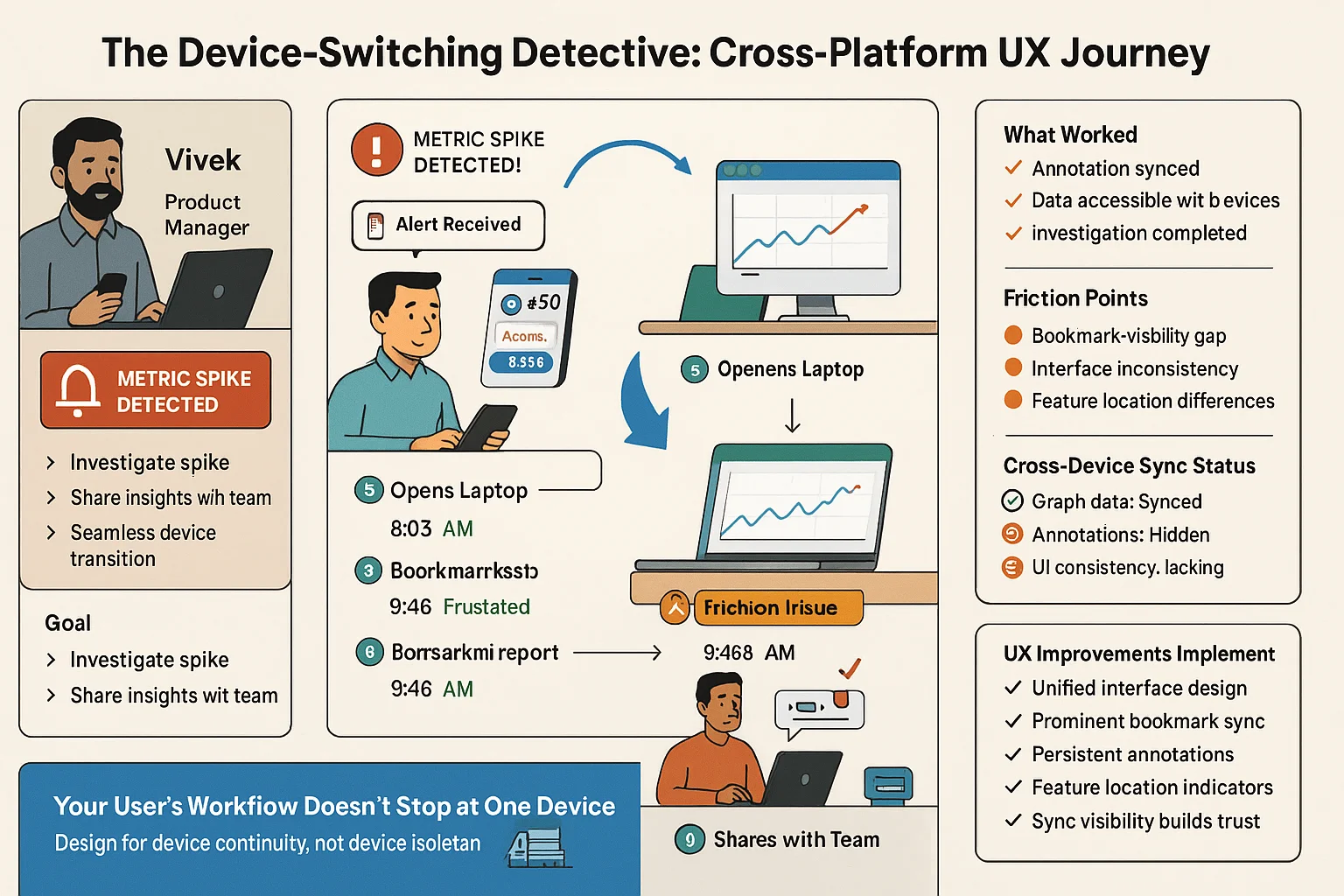

Example 3: Switching devices during a task

- Persona: Vivek, a product manager working on a machine‑learning dashboard (I avoided the banned term).

- Context: He starts researching metrics on his phone while commuting, then continues on his laptop at the office.

- Trigger: He sees an alert that a metric has spiked.

- Goal: Investigate the spike and share insights with his team.

- Steps:

- On mobile, he opens the dashboard and glances at the graph.

- He annotates a section of the graph to highlight the spike.

- He bookmarks the report for later.

- At the office, he opens his laptop; the annotation syncs but the bookmark is not obvious.

- He expands the graph, exports data, and writes comments in a chat channel.

- On mobile, he opens the dashboard and glances at the graph.

- Branches:

- If the sync fails, he might lose the annotation.

- If the desktop interface is different from the mobile one, he might spend time searching for features.

- If the sync fails, he might lose the annotation.

- Outcome: With scenario insight, we improved cross‑device consistency and made annotations persistent across platforms.

These examples show how scenarios surface real‑world constraints—network problems, auto‑fill mistakes, cross‑device sync—that do not appear in feature lists. They also help teams prioritise improvements that have a measurable impact on business metrics (reduced drop‑offs, higher repeat use, fewer support calls).

Common mistakes and pitfalls

Even seasoned teams get scenarios wrong. Watch out for these traps:

- Too generic – A scenario that reads like “A user logs in and buys a product” lacks context and motivation. Without specifics, it does not guide design.

- Overly prescriptive – Specifying interface details (e.g., “click the red button”) forces designers into one solution too early.

- Ignoring alternate paths – Real use is messy. Don’t write only the happy path; include errors, recovery and drop‑off behaviours.

- Stale scenarios – Products evolve. Keep scenarios updated as features change.

- Scenario overload – Creating a scenario for every minor feature can overwhelm teams. Focus on the ones that inform major flows or risky behaviours.

- No validation – A scenario is only useful if users recognise themselves in it. Share it with real people.

- Confusing with other artefacts – User stories and use cases have their place, but they are not the same as scenarios. Use each for its intended purpose.

Integrating scenarios into your workflow

Scenarios should not live in a drawer. Here are ways to bring them into daily work:

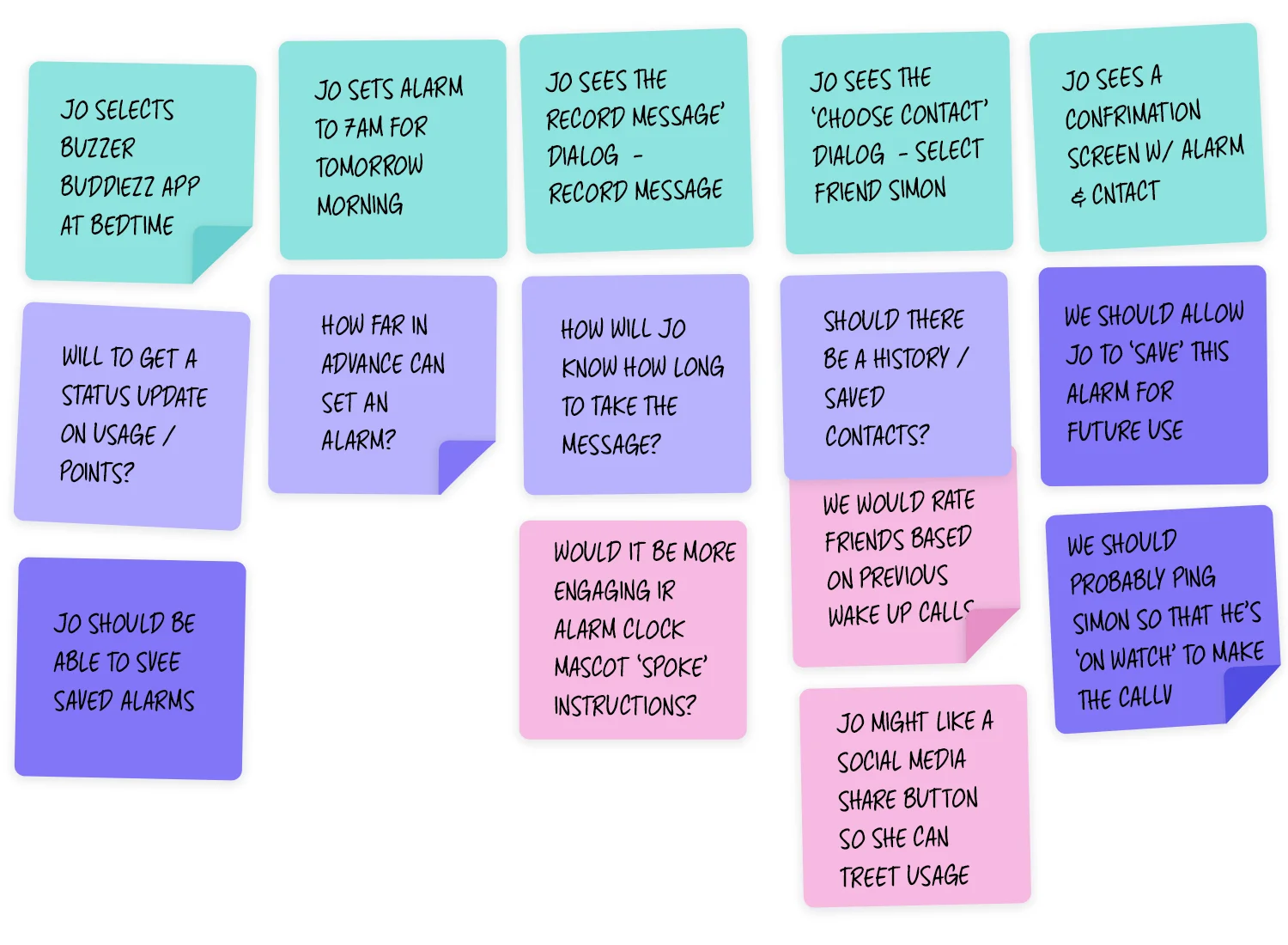

- Scenario mapping workshops – Gather a cross‑functional team and map multiple personas across tasks. Use sticky notes to build flows and identify gaps.

- Pair scenarios with wireframes – When presenting a wireframe or prototype, attach the scenario it supports. This reminds everyone of the context.

- Scenario‑based testing – During usability testing, create tasks that reflect your scenarios. For example, ask participants to book a ride during rain with limited balance.

- Documentation – Include scenarios in product specifications and design docs. They become reference points when scoping features.

- Sprint grooming – When new features emerge, revisit scenarios. Does the new feature address an existing scenario, or does it create a new one?

- Trace dependencies – Map each scenario to user stories and engineering tasks. This ensures a clear line from story to code.

In our studio, we also use scenarios for onboarding. New team members read them to understand why we made certain trade‑offs. This practice builds empathy and speeds up orientation.

Metrics and validation

How do you know if a scenario is “right”? Here are some ways to check:

- User feedback – Share the scenario with real users and ask if it feels accurate. Do they recognise themselves? Does it miss any important detail?

- Usability test success – During tests, measure whether participants complete tasks under scenario conditions. Compare success rates, time to completion, and number of errors.

- Drop‑off analysis – Track analytics data to see if the points where users drop off match those predicted in your scenario. The Tenet report warns that slow loading, unclear navigation and too many steps cause high abandonment.

- A/B tests – Test alternative flows based on scenario variations. Which path performs better?

- Business metrics – Monitor conversion, retention and support tickets. If a scenario aimed to reduce support calls, check if calls decrease after implementing the design.

- Iteration – If analytics contradict your scenario, revise it. Scenarios are living documents.

Research from Optimal Workshop’s 2024 report shows that only 16% of organisations have fully integrated user research into their process. It also found that 56% of companies do not measure the impact of research and that many expect machine‑assisted analysis to play a larger role. These statistics underscore the importance of grounding research in actionable tools like scenarios and demonstrating their impact through metrics.

Recap and key takeaways

We started with a simple question: what is the user scenario? At its core, a user scenario is a narrative description of how a specific person interacts with a system in context. It tells us who the person is, why they act, where they are, and how they move through a task. Unlike a high‑level path map or a brief user story, a scenario is grounded and vivid. It helps teams empathise with users, identify constraints, anticipate edge cases and design flows that work in the real world.

Here are the key points:

- Scenarios bridge the gap between research and design, connecting personas to concrete product decisions.

- They emphasise context, motivation and behaviour, not just system steps.

- They complement other artefacts like user stories and use cases; each has its place.

- Scenarios are most useful early in ideation, before creating wireframes, and during testing and onboarding.

- A good scenario includes persona, context, trigger, goal, steps, constraints and outcomes; it is concise yet vivid.

- Real examples – like booking a ride in a storm or switching devices mid‑task – show how scenarios surface hidden friction and guide design.

- Measuring scenario success requires user feedback, usability metrics and business outcomes. Without measurement, scenarios lose impact.

By integrating scenarios into your process, you create a shared language for your team and a clear path from insight to implementation. As product builders we have a responsibility to make things that people can use with ease. Scenarios help us stay honest about real constraints and design with care.

Frequently asked questions

1) What is an example of a user scenario?

Imagine you’re a working parent who realises you’re out of milk. You open your grocery app, filter by dairy, add milk to your cart with express delivery, pay with your wallet balance and confirm the order – all within two minutes, hoping it arrives before your kids’ breakfast. This is a simple example of what a user scenario is.

2) What is an example of a scenario?

A commuter decides to catch a ride during heavy rain, books via an app, faces surge pricing and may cancel if the wait exceeds five minutes. The narrative includes context, motivation, actions and potential outcomes.

3) What is the difference between a user story and a user scenario?

A user story is a short statement such as “As a parent, I want to reorder groceries quickly so that I can focus on my kids.” It helps prioritise features. A user scenario is a narrative with context, motivations, steps and alternatives. Stories ask what and why; scenarios ask how and under what constraints.

4) What is the main purpose of creating user scenarios?

The purpose is to ground product decisions in real behaviour, to connect abstract needs to actual workflows and to reveal trade‑offs, friction and edge cases. Scenarios guide design, testing and cross‑team dialogue.

5) How many scenarios should we write?

Focus on the most critical tasks and personas. Too many scenarios can overwhelm your team. Prioritise those that address high‑impact behaviours, risky flows or common pain points.

By following these guidelines, you’ll be better equipped to craft scenarios that make your products more humane and your teams more aligned. If you’d like to discuss how to implement this in your organisation, reach out – I’d love to help.

.avif)