Value Proposition in Business Model Canvas: Guide (2026)

Learn how to craft a compelling value proposition within the Business Model Canvas to define customer benefits and competitive advantage.

You built something you’re proud of, but the market isn’t responding; people tinker and move on. Investors ask, “Why you?” and your answer is fuzzy. At Parallel we see talented founders struggle to explain why their product matters. That gap isn’t just messaging – it’s strategy. In this piece I’ll explain what a value proposition is in a business model canvas, why it sits at the heart of your model and how to design and test it like a pro. We’ll map customer needs, translate them into benefits and build a statement that sets you apart. By the end you’ll know how to craft, test and refine a clear promise that connects with the right people.

What is the Business Model Canvas?

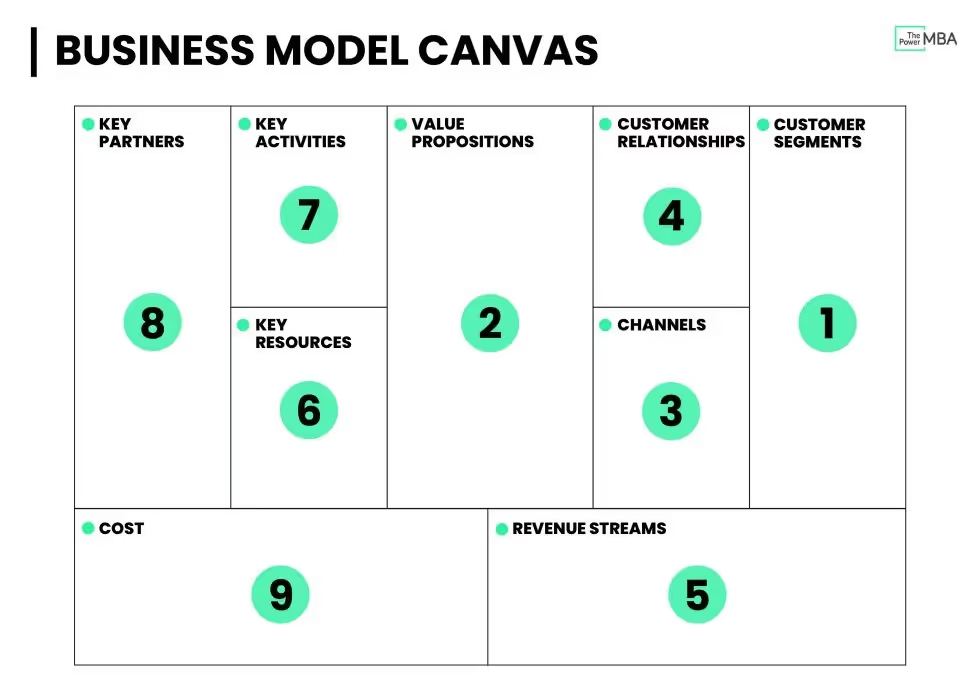

The Business Model Canvas (BMC) is a one‑page view of how your company works. Alexander Osterwalder created it to replace long business plans with a simple visual tool. It breaks a business into nine building blocks: customer segments, value proposition, channels, customer connections, revenue streams, essential resources, main activities, partner relationships and cost structure. Filling out each block forces you to answer a set of questions about who your customers are, how you reach them, how you make money and what you need to deliver.

In the canvas, the value proposition sits at the centre. It links what you offer to whom you offer it – the glue between your solution and your audience. A clear value proposition aligns your product, marketing and revenue streams. If it’s vague or doesn’t match the needs of your segments, the rest of the canvas falls apart. Conversely, a well‑crafted promise guides how you design features, choose channels and price your product.

What is a value proposition?

Strategyzer describes a value proposition as a statement that clearly outlines the unique benefits a company offers its customers. It isn’t a slogan. Codica explains that it answers why customers choose you over others; it’s a group of benefits that can include innovation, performance, distinctive design, accessibility or convenience. Shopify adds that it should highlight the problem you solve and why your product is superior, while HubSpot notes that it is the specific solution and promise of value customers can expect.

Why does it matter? A strong value proposition differentiates you in crowded markets, attracts the right customers and guides marketing and product decisions. McKinsey research found that companies with clear, customer‑centric promises achieved more than double the revenue growth of laggards between 2016 and 2021. Without a clear proposition, buyers may choose competitors simply because their messaging is clearer.

When founders ask what is the value proposition in a business model canvas, this section offers a direct answer: it is the core promise that connects your solution to your audience. The canvas shows nine blocks, but none matter if you can’t articulate your promise. The following sections build on this question.

Customer needs and market context

Value creation vs. value capture

Every business must create value for its customers and capture value for itself. Value creation means giving people something meaningful: relieving a pain, fulfilling a desire or enabling a desired outcome. Value capture is how you convert that into revenue – pricing, monetisation and margins. Your value proposition sits at the intersection: it needs to promise a benefit that customers care about and that you can monetise. Founders sometimes over‑engineer features that they think are cool but that don’t solve urgent problems. Others build something valuable but give it away or price it too low to sustain the business. The best propositions are anchored in real customer pains and gains and supported by a viable revenue model.

If you’re still unsure what a value proposition is in a business model canvas, think of this balance: your promise must create value for users and capture enough of it for your company to thrive. The phrase encompasses both sides of that equation.

Understanding customer needs and jobs to be done

Before you can craft a proposition, you need to understand what your customers are trying to accomplish. The Jobs‑to‑Be‑Done (JTBD) framework is a useful lens. Rather than focusing on demographics, it asks what “job” people hire a product to do. GreatQuestion’s JTBD guide explains that customers hire products to fulfill functional, emotional or social jobs. For instance, a parent might hire a meal planning app not just to generate recipes but to feel less stressed about weeknight dinners (emotional job) and to be seen as organised by their family (social job). Understanding these jobs requires research: interviews, surveys and observation. Only then can you map pains (what frustrates them) and gains (what they aspire to achieve) before jumping into features.

From needs → value creation → product benefits

Once you know the jobs, pains and gains, you can design pain relievers and gain creators. Pain relievers remove obstacles; gain creators enable positive outcomes. Codica summarises the value proposition as a group of benefits you offer. To move from needs to benefits, translate each pain into a specific outcome. If your customers’ pain is “spending too much time scheduling meetings”, the pain reliever could be an automatic scheduling tool. The benefit isn’t the feature (“calendar sync”) but the outcome (“save two hours a week”). Likewise, gain creators might be intangible: feeling confident, being part of a community or improving social status. Your final proposition should emphasise these benefits, not the underlying technology.

Answering the value proposition in the business model canvas starts with this work. Without understanding jobs, pains and gains, you’re guessing at benefits. Research grounds your promise in real needs.

Unique selling point and differentiation

A unique selling point (USP) is the specific feature or aspect that differentiates your product. Varify’s 2025 guide warns that people often confuse the value proposition with the USP, positioning or mission. The USP is often product‑centred (e.g., “fastest onboarding”), while the value proposition bridges product benefits and customer needs. A good proposition should incorporate differentiation, but it must speak to the problem you solve. In crowded markets – such as artificial intelligence, where nearly a third of seed deals on AngelList in 2024 involved artificial intelligence startups – differentiation is essential. Think about what makes your offer distinct: a protected technology, a new distribution strategy, superior service or a novel business model. Then weave that into your promise without slipping into jargon.

Many founders confuse the value proposition with a USP. Understanding the difference will help you avoid pitching a feature as if it were a promise.

Problem solving and customer benefits

Frame your value proposition as a solution to a specific problem. Avoid listing features; focus on benefits. In practice, that means telling customers how your product will make their life better: save time, save money, reduce stress, boost confidence or improve status. Codica’s case study of a boat marketplace demonstrates this: after redesigning their platform, the company saw lead generation growth of 480 percent. The benefit wasn’t just new colours; it was improved usability that converted more visitors. When you articulate your proposition, tie every feature back to the benefit it delivers.

Market demand and competitive advantage

Your proposition must reflect real market demand. Building something nobody wants is the fastest route to failure. Early‑stage founders sometimes chase trends without validating that people will pay. AngelList’s 2024 venture report shows that nearly one‑third of seed deals were in artificial intelligence, which means dozens of similar solutions competing for the same dollars. In saturated spaces, your advantage may come from being better (higher performance), faster (quicker results), more affordable, simpler or more trustworthy. InnovationWithin notes that a clear proposition not only improves conversion rates but sharpens the entire business model. Without such clarity, your strategy remains arbitrary.

Designing your value proposition

The role of value proposition in the BMC

On the Business Model Canvas, the value proposition block touches four others: customer segments, channels, customer connections and revenue streams. You need to define whom you serve, how you communicate and deliver the offer, and how you capture revenue – all shaped by your promise. A mismatch between these blocks and your proposition causes friction. For example, if your promise is quick, self-serve convenience but your only channel is sales calls, you’re sending mixed signals. Likewise, if you promise enterprise‑grade reliability but offer a free model with no support, you’ll attract the wrong audience. Alignment across the canvas keeps your model coherent.

Filling in the value proposition box

When filling the canvas, break the value proposition into three elements:

- Products & services – the tangible offerings or features.

- Pain relievers – how those offerings ease customer pains.

- Gain creators – how they enable desired outcomes.

Map each element to the corresponding customer jobs, pains and gains. Use research to rank pains and gains by urgency. Focus on the top few rather than trying to address everything. This selective focus is an essential principle from Strategyzer: emphasise a handful of jobs and pains rather than all. Also separate features from benefits: “24/7 support” is a feature; “peace of mind” is the benefit. Keep your statements specific and testable.

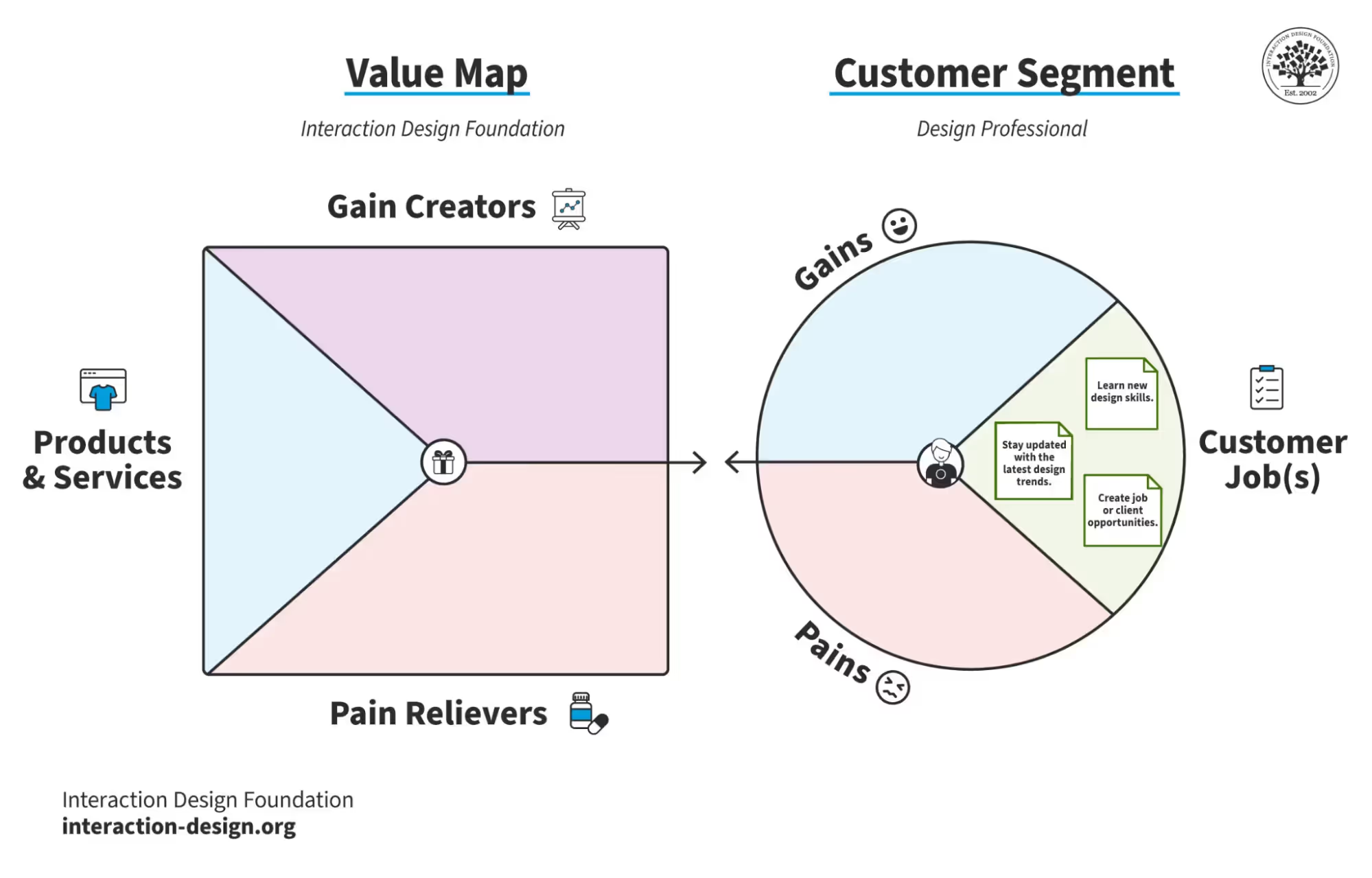

The Value Proposition Canvas explained

The Value Proposition Canvas (VPC) is a tool that zooms into the value proposition block of the BMC. It has two sides:

- Customer Profile – lists the jobs, pains and gains of a segment. Jobs can be functional (tasks), emotional (feelings) or social (perception). Pains are obstacles or anxieties; gains are desired outcomes or aspirations.

- Value Map – describes your products and services, pain relievers and gain creators. Each element in the value map should relate directly to an item in the customer profile.

The goal is fit: a clear match between what the customer cares about and what you offer. When the fit is weak, revisit your assumptions. Use the canvas to test hypotheses rather than view it as a static document.

Six components of the VPC

The Value Proposition Canvas has six elements across two columns: customer jobs, pains and gains on one side, and your products, pain relievers and gain creators on the other. Jobs describe tasks and aspirations; pains are frustrations and risks; gains are desired outcomes. On the solution side, list what you offer, how it removes pains and how it creates gains. Asking simple questions – “what is the person trying to do?”, “what stands in their way?”, “what would delight them?” – will help you match your offer to the jobs and pains that matter most.

Best practices and common mistakes

- Focus on critical jobs and pains. Don’t attempt to solve every problem. InnovationWithin recommends focusing on a few important jobs and pains rather than all.

- Validate assumptions early. Talk to potential customers. GreatQuestion’s JTBD guide encourages interviewing to uncover motivations.

- Separate features from benefits. Shoppers care about outcomes, not technical specs. Codica notes that value propositions should list benefits such as improved performance, accessibility or convenience.

- Don’t overpromise. Be honest about what your product does. Verify warns that over‑general claims or vague benefits erode trust.

- Keep it specific and testable. Your promise should be measurable. If you say “save hours each week,” measure it with customers.

- Iterate. View your proposition as a hypothesis that changes with feedback and market shifts.

Process, example and testing

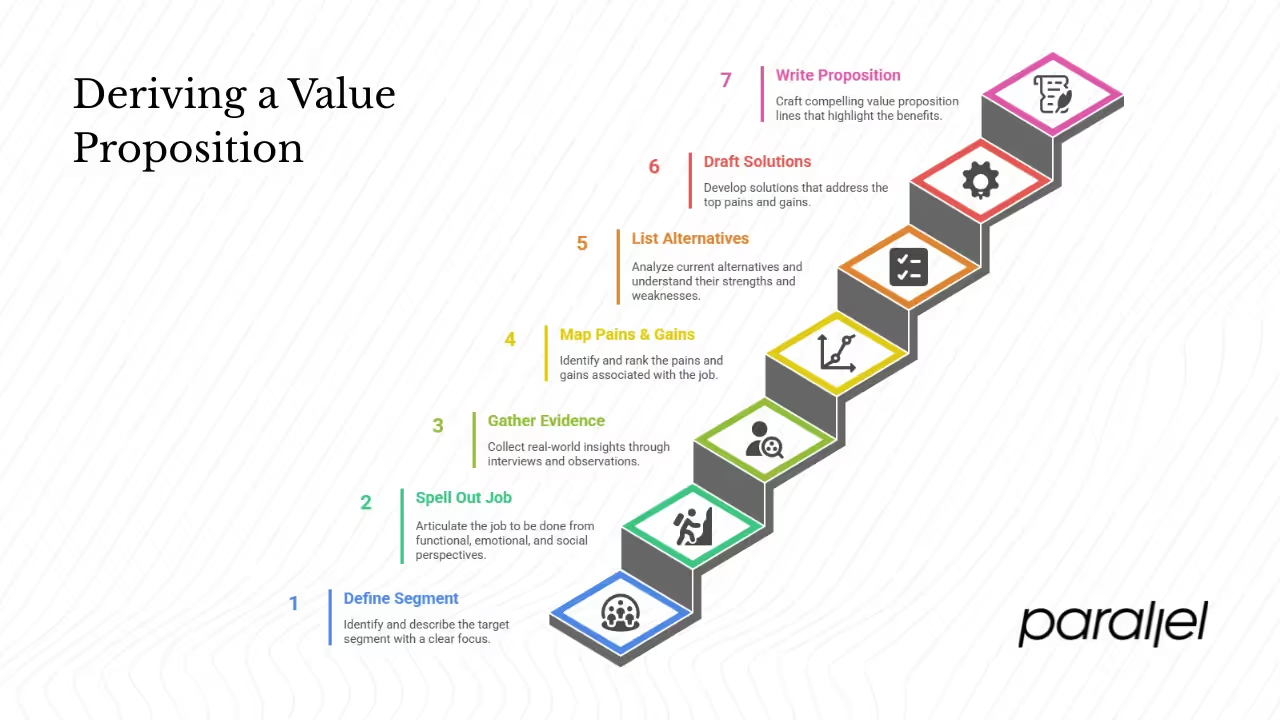

Step‑by‑step process to derive a value proposition

- Pick one segment (and only one)

- Describe who they are, the job context, and must-have traits.

- Write a short “who it’s not for” line to keep focus.

- Output: a one-sentence segment definition.

- Spell out the job to be done

- What are they trying to get done? In what situation? What does “done” look like?

- Capture functional, emotional, and social angles.

- Output: a brief job statement (situation → struggle → desired outcome).

- Gather evidence from real people

- Run 8–12 short interviews. Add 3–5 observations or screen shares of how they do it today.

- Ask for stories, not opinions. Save verbatim quotes.

- Output: raw notes and quotes tagged as “job / pain / gain / workaround.”

- Map pains and gains, then rank them

- List pains (obstacles, risks, frictions) and gains (outcomes they want).

- Score each 1–5 for severity (pain) or importance (gain) and 1–5 for frequency.

- Multiply to get a priority rank. Keep the top 3–5 only.

- Output: a ranked pain/gain table.

- List current alternatives

- What do they use now? Products, spreadsheets, agencies, hacks.

- Why those? What they like and hate about them.

- Output: a quick “why we switch / why we stay” grid.

- Draft solutions that hit the top items

- For each top pain/gain, write 1–2 “ways we solve it.”

- Check feasibility (can we deliver this soon?) and edge (what makes it different?).

- Prioritise with an Impact × Effort matrix. Keep 3–4 core moves.

- Output: a shortlist of features/benefits tied to specific pains/gains.

- Write three proposition lines

- Use this snap-tight format and create three variants:

- Use this snap-tight format and create three variants:

- “We help [segment] [complete job] by [solution], so they get [primary benefit], unlike [main alternative].”

Example – scheduling tool for professionals

- Customer segment: professionals who juggle meetings across time zones.

- Jobs: schedule meetings efficiently (functional), avoid back‑and‑forth emails (emotional), appear organised and responsive (social).

- Pains: wasted time finding mutual availability, misaligned time zones, missed appointments.

- Gains: save hours, reduce no‑shows, appear professional.

- Value proposition statement: “We help busy professionals automate meeting scheduling, saving them at least two hours per week and reducing no‑shows, so they can focus on their work instead of calendars.”

This example shows how a proposition can quantify the benefit and differentiate from manual scheduling. It answers the reader’s question: what’s in it for me?

When you craft your own statement, return to the central question of what promise you are making. Express benefits in plain language that speaks to the customer’s outcome rather than technical specifications.

Value proposition templates and formulas

You can use simple formulas to draft your statement. Here are a few:

- Outcome‑focused: We help [segment] achieve [desired result] through [solution], giving them [primary benefit] compared to [alternative].

- Problem‑solution: [Segment] struggle with [pain]. Our [solution] removes that pain by [pain reliever], resulting in [gain].

- Job‑to‑be‑done: When [trigger], [segment] want to [job]. Our [product] enables them to [job outcome] so they [gain].

Start with one of these, then refine it with customer language and data.

These structures are guides, not formulas to copy. Use them to articulate what is a value proposition in a business model canvas in words your customers would use.

Testing and iterating your proposition

Start with qualitative feedback: share your draft promise with potential users and ask whether it reflects a real problem and if they would pay to solve it. Listen for unprompted excitement or confusion. Then turn to quantitative methods such as A/B tests on landing pages and surveys to see which version drives more sign‑ups and has higher clarity. If evidence shows your promise doesn’t connect or if the market shifts, adjust it accordingly. Your proposition should change as you learn and as the market evolves – revisit it when you add major features or enter new segments to make sure it still fits.

Linking the value proposition to broader strategy

A strong value proposition has ripple effects across your company: A clear value proposition ripples through your whole business. It shapes how you describe yourself and influences the story you tell. It guides product decisions and marketing channels: if your promise is about saving time, invest in automation and self‑service channels. It affects pricing and growth plans: premium promises justify premium prices, while cost‑saving promises point to subscription models. When the promise and the rest of your model fit poorly, the symptoms show up as low sign‑ups, high churn or confused messaging. Recognising this connection helps you make choices that support your promise and avoid wasted effort.

Conclusion

Understanding what a value proposition is in a business model canvas means more than ticking a box. It’s about crafting a clear promise tied to a real need and then using that promise to guide how you build, market and monetise. Map jobs, pains and gains, translate them into benefits, write a concise statement and refine it through testing. Use the Business Model Canvas to check that your promise fits your segments, channels and revenue, and the Value Proposition Canvas to zoom in on fit.

From our work with early‑stage teams, we’ve learned that investing in customer research and specificity pays off. Sketch your own canvas: list the top pains and gains, map pain relievers and gain creators and craft one sentence capturing your promise. Share it with users, listen to their reactions and adjust. Your promise is a living hypothesis that should grow with your business.

As you finish this piece, ask yourself again: what is the value proposition in the business model canvas for your company? Crafting and testing that answer is some of the most valuable work you can do as a founder or product leader.

FAQ

1) What is the value proposition in the business model canvas example?

A value proposition in the Business Model Canvas is the promise connecting your offer to a specific customer segment. For instance, a scheduling tool might say: “We help busy professionals automate meeting scheduling, saving them hours each week and reducing no‑shows compared with manual scheduling.”

2) What is a value proposition and example?

A value proposition is a brief statement explaining why a customer should choose your product over alternatives. Dropbox’s early promise – “Get your files anywhere, safe and synced” – made it clear that the service offered convenience and security without USB drives.

3) What are the six components of the Value Proposition Canvas?

The Value Proposition Canvas has six building blocks: customer jobs, pains and gains describe what people want to achieve, what frustrates them and what outcomes they seek; products & services, pain relievers and gain creators describe what you offer, how it removes pains and how it delivers gains.

4) What is meant by Value Proposition Canvas?

The Value Proposition Canvas is a tool that zooms into the value block of the BMC by mapping customers’ jobs, pains and gains to your products, pain relievers and gain creators, helping you check that what you offer matches what your customers actually need.

.avif)